Film & Movies

Be Careful What You Wish For – The Story of Robin Williams and Disney Films

In this April 2000 piece from the archives, Jim Hill exposes what really happened with comic genius Robin Williams and the Walt Disney Company's handling of the film "Aladdin" and looks at the tense relationship since.

Spring 1991: Robin Williams was suited up in green tights and hanging from a wire when he got the call.

It was then Disney Studio head Jeffrey Katzenberg on the line. Realizing that Robin was busy filming Steven Spielberg’s big budget Peter Pan update, Jeffrey apologized for the intrusion. But the Mouse had a real problem with an animated film they had in the works. So Katzenberg was wondering if Williams — who was well known in the industry as a big-time toon buff — might drop by Burbank and offer his opinion of the project.

Given that “Hook” was already running weeks behind schedule, Robin should have said “No.” But Williams had a soft spot when it came to the Mouse.

After all, Robin pretty much owed his film career in the 1990s to Disney.

“Good Morning Vietnam” & “The Dead Poets Society” – Early Robin Williams Disney Films

After starring in a string of cinematic stinkers like “Club Paradise” and “The Survivors,” Williams virtually couldn’t get arrested in Hollywood by the mid 1980s.

Then there was the very public collapse of his first marriage as well as rumors of drug and alcohol addiction.

Things were looking pretty bleak for the comic back then

But — in 1987 — Disney decided to take a chance on Robin. Figuring that the failures of his earlier films were due mainly to a poor marriage of performer and material, Disney sought to create a movie that would be a showcase for William’s gift for comic improvisation.

Katzenberg & Co. spent weeks looking for just the right piece of material for Robin. Finally — when Disney learned that Paramount Pictures had just put in to turnaround a script about an Armed Forces Network disc jockey and his adventures during the early days of the Vietnam War — Jeffrey knew that they had found the perfect vehicle for Williams. So the studio quickly snatched up the rights to “Good Morning, Vietnam.”

Williams — who was grateful for any opportunity to work at this point in his career — jumped at the chance to appear in this film. He even agreed to Disney’s less-than-generous financial terms, getting half of his usual $2 million paycheck to portray DJ Adrian Cronauer.

In the end, Disney’s gamble on Williams paid off handsomely. “Good Morning, Vietnam” proved to be a huge hit at the box office in the Winter of 1988. Both critics and audiences loved Robin’s performance. The role even earned him his first ever Academy Award nomination for best actor.

Disney decided to build on Williams’ success in “Good Morning, Vietnam” by starring the comic in another film for the studio, 1989’s “The Dead Poets Society.” Directed by noted Australian film-maker Peter Weir, this coming-of-age drama was also proved to be a huge hit with the movie-going public. Williams’ performance as devoted teacher John Keating earned Robin his second Oscar nomination as well as established him as a gifted dramatic actor.

Thanks to these two films, Robin Williams’ movie-making career came roaring back to life. All because Jeffrey Katzenberg had decided to take a chance on a semi-washed up comedian.

Which is why Robin Williams thought he would be forever grateful to the Mouse…

Or so he thought.

Saying Yes to “Aladdin” – Robin Williams Becomes the Genie

Anyhow, due to this sense of personal and professional obligation, Robin agreed to drop by Disney Studios on his very next day off from “Hook.” Less than a week later, Williams found himself in a meeting with Katzenberg as well as Disney animators John Musker, Ron Clements and Eric Goldberg.

Jeffrey thanked Robin for dropping by, then explained Disney’s dilemma: Feature Animation had just had one of its latest projects, a new musical version of “Aladdin,” spin into the dirt. The film’s screenwriter and lyricist Howard Ashman had tragically died from AIDS a month or so earlier. The “Aladdin” script Ashman had left behind had a lot of interesting things in it. But — structurally and story-wise — it was a mess.

Katzenberg then explained to Williams that the studio was thinking of junking Ashman’s screenplay. They’d hang on to most of Howard’s wonderful lyrics. But — beyond that — Disney was thinking of taking this animated musical in a whole new direction.

That said, Jeffrey directed Robin’s attention to a nearby TV monitor. There on the screen was an animated Robin Williams — doing a routine from his 1979 “Reality … What a Concept” album. The cartoon Williams announced that “Tonight, I’d like to talk to you about schizophrenia.” The toony Robin then grew a second head, which quickly told the first head to “Shut up! No he doesn’t!”

Williams was thoroughly charmed by the footage. Animator Goldberg — who had personally put together the test animation — had done a masterful job of transforming Robin’s comic genius into toon form. Turning back to Jeffrey, Williams then asked what it was that the Mouse wanted him to do now.

Katzenberg laid it on the line: We’d like you to join the cast of “Aladdin” as the voice of the Genie.

Williams hesitated for a moment. After all, the coming year was going to be one of his busiest ever, professionally. Once Robin finished playing Peter Pan in “Hook,” he’d leap right into work on “Toys.” This whimsical military satire set behind-the-scenes at a toy factory was a project that Williams was really looking forward to — for it would re-unite him with his “Good Morning, Vietnam” director, Barry Levinson. Between all the work he’d have to do to complete these two special effects-laden films, there just didn’t seem to be enough time to squeeze in an animated film for Disney.

But Jeffrey persisted. “Think of your son, Zachary,” Katzenberg said, “Or your daughter, Zelda. Wouldn’t they love to see their dad starring in a Disney animated film?”

That was the argument that finally won Williams over to doing “Aladdin.” Since so many of his earlier films had been rated R or PG, Robin’s children had yet to really see their daddy perform on the big screen. But here now was a movie that Williams could proudly take his kids to see on its opening day.

That was enough to win Robin over to the idea of doing the voice of the genie. However, this is not to say that Williams didn’t have a few conditions he wanted Disney to agree to before formally signing up to work on “Aladdin.”

Conditions for “Aladdin”: Robin’s Other Film -“Toys”

Chief among these conditions was Robin’s insistence that Disney Studio could not use his name or image in any theatrical posters, print ads, movie trailers or TV commercials to promote “Aladdin.

What was the deal here?

Was Robin pulling some sort of silly star trip on the Mouse?

No, not at all. It was just that Williams’ next live action film, “Toys,” and the animated “Aladdin” were due to be released within weeks of one another. “Aladdin” would roll into theaters over the 1992 Thanksgiving weekend, while “Toys” would be released in December.

Robin had agreed to do “Toys” first, so Williams felt that his primary loyalties had to lie with Levinson and his movie. Disney was free to promote “Aladdin” any way that they saw fit. Just so long as they didn’t create the impression that their animated film starred Robin Williams.

After all, the Genie was just a supporting role in “Aladdin.” So Robin asked that all ads for Disney’s film reflect that reality, and not give the false impression that the animated film somehow starred Williams’ character.

Jeffrey smiled and assured Robin that Disney Studios would be happy to meet his conditions.

However, the Mouse also had a few conditions of its own.

As much as Disney wanted Williams to play the voice of the Genie, the studio just wasn’t willing to pick up Robin’s now standard $8 million-per-picture paycheck. Since Disney would only be using Williams’ voice — which the Mouse could record in just a few quick studio sessions — in the movie, would Robin be willing to work for a significantly smaller fee?

Like — say, maybe — scale? Screen Actor Guild minimum. $485 a day.

Williams’ agent — the then all-powerful head of Creative Artist Associates (CAA) Michael Ovitz — thought the deal Disney was offering Robin was absurd. If the Mouse wasn’t willing to pay for Williams’ services up front, Ovitz insisted that the very least they could do was offer Robin a piece of the movie’s back end.

Williams told Ovitz to butt out. After all, he wasn’t making “Aladdin” to make money. Robin was making this movie so that Zachary and Zelda could see their daddy in a Disney movie.

“Besides,” Williams continued, “This is animated. How much money could the movie make, anyway?”

How Much Can an Animated Movie Make in the Early 90s?

From our position (current day), where a “Lion King” can earn a billion dollars at the box office plus a billion more off of toys, games, videos, etc. — Williams’ statement seems awfully naive. But please remember that Robin was talking to Ovitz back in the Spring of 1991. Disney’s latest animated film, 1990’s “The Rescuers Down Under,” had just under-performed at the box office. And while it was true that 1988’s “The Little Mermaid” had earned $80 million domestically, that film’s performance seemed more like a fluke than the start of a trend.

Williams had no idea that Disney’s “Beauty and the Beast” was lying out there in the bushes, getting ready to change forever the way people viewed animation. When that film hit theaters in November 1991, it racked up great reviews and huge box office numbers. By the spring of 1992, that movie would gross over $140 million as well as earn the first ever “Best Picture” nomination for a feature length animated film.

$140 million seemed like an extraordinary amount for an animated film to make. But “Aladdin” — with its $217 million gross — did better than “Beauty and the Beast.” And 1994’s “The Lion King” — with its $350 million — did even better than that.

But Williams had no idea that any of this was going to happen. He had no clue that animation was about to become really big money for the film industry. Robin just wanted to make a movie that he could take his kids to see.

But — more importantly — Williams wanted to pay Katzenberg & Co. back for all the kindness Disney had showed him in the mid-1980s. If the Mouse hadn’t taken a chance on him and “Good Morning, Vietnam,” Robin’s film career might still be on the skids. So, if the Walt Disney Company wanted to keep costs down on “Aladdin” by only paying him scale for his recording sessions, that was okay by Robin.

So Williams agreed to Katzenberg’s proposal — working for scale — provided, of course, that the studio honored Robin’s request to keep his names out of all the “Aladdin” ads.

“Hook”, “Toys”, and “Aladdin” – Robin Williams Busy Schedule

Robin kept his end of the bargain. Over the next 18 months, while working on “Hook” and “Toys,” Williams would slip away for a day or two every month for recording sessions on “Aladdin.” At each of these session, he’d start off with just straight readings of the scenes he was given from Terry Rossio and Ted Elliot’s screenplay. But — once those sequences were recorded — Robin would begin to ad-lib additional dialogue for each of these scenes.

Musker and Clements loved the material Williams was inventing for the Genie. So much so that they began reworking “Aladdin” so that the Genie went from a minor supporting role in the film to a part that was almost as big as the title character’s.

This is where things started to get difficult for Katzenberg. All the test screenings Disney Studio held for their still-in-production animated film showed that “Aladdin” was going to be a huge hit. Maybe even bigger than “Beauty and the Beast.”

But — when they polled the audience after each test screening as to who their favorite character in the film was — Disney found that the audience just loved the Genie. The very character that Jeffrey had promised Williams that the studio would do nothing to promote.

Now here was Katzenberg’s dilemma: How could he honor his agreement with Williams and not mention his name in any of the film’s ad, yet still somehow clue people in to the comic’s incredible vocal performance in the movie?

Using the Genie in the Promo Material for “Aladdin” – Robin Williams and Jeffrey Katzenberg Battle

A last minute re-negotiation of Disney’s deal with Williams made Katzenberg’s job somewhat easier. Jeffrey convinced Robin that — since the Genie was featured prominently in 25% of “Aladdin”‘s running length — the character should be featured in 25% of every movie trailer, print ad, TV commercial and lobby poster for the film. After getting Katzenberg’s assurance that all this revamped advertising would not give the audience the false impression that Williams’ character was the star of the movie, Robin okayed the change.

“Aladdin” Theatrical Poster

But — as soon as Williams got his first glance of the original theatrical poster for “Aladdin” — he immediately regretted changing the terms of his deal with Katzenberg. Sure, the Genie was only featured on 25% of the poster. But his big blue face was the largest image on the thing. His smiling mug towered over the film’s title, while infinitely smaller images of Aladdin and Jasmine riding their magic carpet appeared toward the bottom of the poster. While Williams’ name was nowhere to be found on the poster, it was clear to Robin that Disney was trying to get across the message that his character was the biggest thing in “Aladdin.”

Williams complained loudly to Katzenberg’s office about the imagery used in the “Aladdin” movie theater poster. Jeffrey apologized, but pointed out that he had honored the exact conditions of their deal. Robin’s name WAS nowhere to be seen on the poster. More importantly, the Genie’s image did only took up 25% of the surface space of the poster. Katzenberg had honored the language of their agreement, even if the poster’s imagery totally violated the spirit of their deal.

Fearing that featuring his character so prominently in the movie’s posters and ads would sink “Toys” chances at the box office, Williams asked that all the original “Aladdin” advertising material be recalled and new posters be issued. Katzenberg again said he was sorry, but there was no way that was going to happen. Disney had already spent millions launching “Aladdin.” Any changes in advertising imagery would just have to wait till the film’s secondary release, when the studio would create new ads and posters … maybe.

Robin was furious at the way he felt Jeffrey had mislead him in regard to the way Disney was advertising “Aladdin.” And this would not be the last time Williams and Katzenberg would clash over the way the studio chose to hype the the film.

The Genie on Posters at American Bus Shelters

Just after “Aladdin” opened, Williams was driving through downtown Los Angeles and was shocked to see that many of the city’s bus shelters featured huge blue posters of the Genie. No other characters from “Aladdin” were featured in these enormous public advertisements. Just the Genie.

When Williams called Katzenberg to complain about the bus shelter posters, Jeffrey apologized profusely. “Obviously, there must have been some sort of mix-up,” the then-Disney Studio head said. “I’ll have them removed immediately.”

So all 300 of the LA area “Aladdin” bus shelter posters were recalled and destroyed. It was only later that Williams learned that thousands of these huge blue Genie posters had been created and had been installed in bus shelters all over the country, where they remained up for the entire time “Aladdin” was in theaters. Only the big blue Genie bus shelter posters that were in areas where Williams was likely to see them had been removed.

This was typical of Katzenberg’s abuse of his “Aladdin” advertising agreement with Williams. Time and again, Jeffrey would pay lip service to Robin — saying that he was doing everything he could to make sure that Disney’s marketing department honored their deal concerning all aspects of the advertising on “Aladdin.” But, once that phone call was over, Katzenberg would then turn around and tell the studio’s marketing guys that they could do whatever they wanted to help promote the film.

“Toys” Disappointment

Just as Williams had feared, the Thanksgiving release of “Aladdin” totally over-shadowed the December release of “Toys.” Sure, this Barry Levinson film’s chances for success at the box office were hobbled by the vicious reviews this limp comedy received. But — had it been the only Robin Williams film in the marketplace that holiday season — “Toys” might have still done some business.

Unfortunately, for Christmas 1992, movie-goers had two Robin Williams films to chose from. 99.999% of the holiday audience opted to go see “Aladdin.” So “Toys” sank like a stone, barely taking in $23 million (which was less than half of the film’s production costs).

As “Toys” sank and “Aladdin” soared, Williams just didn’t know what to think.

On one hand, Robin was thrilled at “Aladdin”‘s amazing success.

Week after week, it was number 1 at the box office.

On the other hand, Robin felt incredibly guilty, thinking that Disney’s relentless advertising of “Aladdin” had snuffed out “Toys” (a film his friend Levinson had labored for 15 years to get made) only chances of ever finding an audience.

Then there was the performer’s ambivalence toward all the praise Williams was receiving for his work in “Aladdin.” Time and again, people would come up to Robin and tell him his performance in the animated film was his best thing he’d ever done. Initially, Williams enjoyed these compliments — until he realized that people were saying that his very best work was in a cartoon, a medium that only made use of an actor’s voice, not his face. This is the sort of thing that can really start to bug a guy who studied at Juilliard.

Awards and the Final Straw for the Genie

Williams’ ambivalence toward “Aladdin” became public knowledge in February 1993, when he received a certificate of special achievement for his work in the film at the Golden Globes. As he went up on the stage, the clearly uncomfortable Robin didn’t know what to say about this alleged honor. He jokingly asked the celebrities and foreign film critics assembled for the ceremony, “Is this like a coupon I can turn in to get a real award?”

Oddly enough, it was Disney’s attempt to capitalize on Williams’ win at the Golden Globes that proved to be the final breaking point between the Mouse and Mork. Katzenberg okayed a brand new series of print and TV ads for “Aladdin.” Each of these clearly mentioned Williams’ name, prominently playing up the award the Foreign Film Critics Association had honored the comic with.

As the then-head of Disney Studio, Jeffrey thought that he was just doing his job by okaying these ads. After all, the Golden Globes are considered by many in the film industry as a prelude to the Academy Awards. If Williams’ work as the Genie in “Aladdin” had been honored by the Foreign Film Critics Association, maybe the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences could also see their way clear to honoring Robin. Maybe they could even give him a special Oscar for the best vocal performance in an animated film. Hey, stranger things have happened.

However, when Williams saw these new ads, he finally blew his top. This was the last straw as far as the comic was concerned. Robin had deliberately asked Katzenberg to keep his name out of any “Aladdin” advertising. Now here was his name prominently displayed in ads throughout the trades as part of Disney’s Oscar campaign for the film.

Robin phoned Katzenberg and told the studio chief that he had repeatedly broken his word to the performer. As a result, Williams felt that he could no longer trust any executives associated with the Mouse Works. Robin then vowed that he would never again make another film for Walt Disney Studios.

Jeffrey Katzenberg Attempts to Win Over Robin Williams

Jeffrey — who was in the middle of orchestrating a million dollar ad campaign that would hopefully help “Aladdin” win a few Oscars — was horrified by what he called “Mork’s melt-down.” Sure, maybe Katzenberg had gone back on his word a few times concerning the film’s advertising. But couldn’t Robin see that Jeffrey had only done this because he had the movie’s best interests at heart? With a domestic gross of $217 million, “Aladdin” was then the highest grossing picture in the history of Walt Disney Studios. Wasn’t Williams thrilled to just to be a part of that enormous success?

Williams was not. In fact, Williams was beginning to feel like a really big schmuck for having agreed to work for scale on “Aladdin.” In addition, many of Robin’s friends in the industry began bad-mouthing the Mouse for not belatedly cutting Williams in on a chunk of the animated film’s enormous success. A very popular joke in Hollywood at the time went something like this:

Q: Why won’t the Mouse write Robin Williams a check for his work in “Aladdin”?

A: You try holding a pen with only four fingers.

Katzenberg tried to make amends with Williams by sending him a Picasso. Jeffrey made sure that word got out that Disney had spent over $5 million to purchase this belated “Thank You” gift for Robin. Imagine Katzenberg’s embarrassment when it later became common knowledge among industry insiders that the studio had picked up the painting at an estate sale for less than $750,000.

In spite of the lavish gift, Robin still refused to have anything to do with the Mouse. For years, he wouldn’t look at the scripts the studio sent him. He returned all invitations to the company’s premieres and/or theme park events. Things looked pretty hopeless…

Until Joe Roth replaced Jeffrey Katzenberg as the head of Disney Studios.

Joe Roth, Marcia Garces Williams, and “Mrs. Doubtfire”

Just like he used to have for Katzenberg & Co, Williams had a soft spot in his heart for Joe Roth.

Why for? Because — before going over to Disney in early 1992 to start up Caravan Pictures — Roth had been in charge of film production at 20th Century Fox. One of Joe’s last official acts as head of that studio was greenlighting production of Williams’ Christmas 1992 hit, “Mrs. Doubtfire.”

Why would this make Williams feel grateful toward Roth? Because “Mrs. Doubtfire” was the first film produced by Marcia Garces Williams — Robin’s wife. Marcia had long been the butt of many cruel jokes in Hollywood, given the unusual way her relationship with Robin began. (Garces had originally been hired by Robin’s first wife, Valerie, to act as a nanny to their son, Zachary. Williams and Garces had an affair that eventually led to the end of Robin’s marriage to Valerie. Garces then became Williams’ personal assistant before finally marrying the comic in 1989.) But “Mrs. Doubtfire” finally dispelled all those rumors about Marcia being Yoko to Robin’s John Lennon.

That film’s big box office gave Marcia huge credibility in Hollywood. All the cruel jokes ended — all because Joe Roth had greenlighted production of “Mrs. Doubtfire.”

Once Joe Roth took over production at Disney Studios, he learned that Francis Ford Coppola was readying a film, “Jack,” that would be perfect for Robin Williams to star in. So Joe had the script messengered to Williams’ home in Sonoma Valley.

Williams quickly returned the script, along with a note that explained that — while he would love to do a film with Coppola — he was no longer willing to work for the Mouse.

Joe then personally called Robin and asked why he didn’t want to work for Disney anymore. Williams went into a long involved explanation of how he felt he had been betrayed by Jeffrey Katzenberg.

Roth then pointed out that Katzenberg no longer worked for the Walt Disney Company. Robin went on to say that — since many of the people who had helped Jeffrey pull a fast one on the comic were still working for the Mouse — even with Katzenberg gone, Williams just didn’t feel comfortable coming back to for Disney.

But Joe wouldn’t give up. “What if the company publicly apologized to you?” he asked Robin.

Williams hadn’t expected something like that. And he was floored when Joe Roth then held a press conference in 1996, where the then-studio chief explained to the media how the Walt Disney Company had wronged Robin Williams. Roth then went on to offer a public apology for all wrongs previous company executives had committed against the comic.

Roth followed up on this press conference by taking out full page ads in many of the industry’s trade papers, explaining that the Walt Disney Company was sorry that it hadn’t honored its agreement with Robin Williams.

Robin was flabbergasted that Joe would go to all this trouble to try and right Katzenberg’s wrongs. He gladly accepted Roth’s apology as well as his invitation to come work at Disney on Francis Ford Coppola’s “Jack.”

Robin Williams Works for Disney Again

In fact, Williams was so thrilled at Joe’s efforts on his behalf that he even agreed to once again provide the voice for the Genie in a direct-to-video sequel to the original “Aladdin” movie, 1996’s “Aladdin and the King of Thieves.”

In turn, Disney was so thrilled to have Robin back as the Genie that they threw out all the recordings Dan Castellaneta (the Genie’s voice for the “Aladdin” TV show as well as the film’s first direct-to-video sequel, 1994’s “The Return of Jafar”) had already made as well as the third of the film that had already been animated.

With Williams once again on board, the animators started from scratch. All the extra effort proved to be worthwhile. Immediately upon release, “Aladdin and the King of Thieves” became the number 1 best selling video in the country.

Did Disney’s renewed relationship with Robin Williams last? Williams made two films for the Disney Company in 1997: a remake of Fred McMurray’s “Absent Minded Professor” comedy called “Flubber” that was Walt Disney Pictures’ big Thanksgiving weekend release for that year; as well as “Good Will Hunting,” a drama produced by the company’s art house subsidy, Miramax Pictures. Williams’ performance as the depressed therapist in that film actually earned him a “Best Supporting Actor” Oscar at the 1998 Academy Awards.

But there was some storm clouds. Williams is said to be upset at how Disney handled his last film for the company, 1999’s “Bicentennial Man.” First the studio announced the project with much fanfare — heralding it as the long awaited re-union between Robin and his “Mrs. Doubtfire” director, Chris (“Home Alone”) Columbus. Then, well after pre-production is underway, the Mouse abruptly canceled the movie, saying that the film’s projected production budget was too high.

Embarrassed by Disney’s behavior but still anxious to make the movie, Williams and Columbus shaved $20 million or so off the film’s production budget. With these cuts in place, Disney then agreed to put “Bicentennial Man” back into production. The film was finally released Christmas Day 1999 and quickly flopped.

Williams reportedly was upset with the way Disney opted to advertise the film as well as the financial restrictions the Mouse placed on Robin and Columbus while making the movie. The comic felt that the $20 million worth of scenes he and Chris cut out of the script to get the film greenlighted again may have destroyed the “Bicentennial Man”‘s chances of ever winning over an audience.

Equally troubling to Williams was Joe Roth’s decision to step down as head of Disney Studios. Who’s started running the show at the Mouse Works? One of Jeffrey Katzenberg’s former lieutenants from Disney Feature Animation, Peter Schneider.

Oh well. It was fun while it lasted.

Film & Movies

The Best Disney Animation Film Never Made – “Chanticleer”

This article is an adaptation of an original Jim Hill Media Three Part Series “The Chanticleer Saga” (August 2000).

Creating a “Don Quixote” Disney Animated Film

For over 60 years, Walt Disney Studios has been trying to turn Cervantes’ satiric stories about the Knight of the Rueful Countenance – “Don Quixote” – into an animated feature. Different teams of artists — in 1940, 1946 and 1951 respectively — have taken stabs at the material, only to be tripped up by the episodic nature of Don Quixote’s tale.

In the early 2000s, it looked like the Mouse might actually pull it off. For Disney had assigned Paul and Gaetan Brizzi — best known as the resident geniuses at Disney Feature Animation France — to tackle the project.

(I know, I know. There are a lot of really talented artists who work for Disney Animation. But — trust me, folks — the Brizzis really are geniuses. Do you remember that jaw dropping opening of “Hunchback of Notre Dame”? That was storyboarded by Paul and Gaetan. How about the “Hellfire” sequence from the same film? That was them too. And Stravinsky’s “Firebird Suite” in “Fantasia 2000”? Yep. That’s the Brizzis again. See what I mean? Geniuses …)

Well, Paul and Gaetan labored mightily for months on “Don Quixote,” turning out elaborate and immense storyboards for the proposed film. We’re talking huge pieces of conceptual art here, folks. Three feet by four feet, done all in pencil. Images that took the breath away of even the most jaded of animators.

But all this artistry was for naught. Management at Disney Feature Animation took a look at all the conceptual material the Brizzis had assembled earlier this year. Even though Paul and Gaetan’s storyboards were beautiful, the brass still took a pass on the proposed film.

Why for? A number of reasons, really. Cervantes’ stories — in spite of their fanciful images of windmills turning into giants and humble country inns becoming castles — don’t really lend themselves to animation. Don Quixote’s adventures tend to start and stop a lot. So it’s hard to turn a series of amusing anecdotes into a coherent dramatic narrative.

Plus the Brizzis take on the material? Intense. Dark. Very adult. Their version of the story actually frightened some of the suits in the Team Disney building. So Tom Schneider thanked Paul and Gaetan profusely for their efforts, then quietly pulled the plug on the project.

So all those great inspirational drawings by the Brizzis came down off the cork board, got carefully packed away, then sent off to the morgue … excuse me, “Animation Research Library” (ARL) … and got tucked away in a drawer someplace.

But that’s okay, folks. Because sometimes when they’re feeling creatively blocked, Disney animators will go down to the ARL and start burrowing through the files. What are they looking for? Images that startle. Drawings that inspire. Pictures that make you say “God, what a great idea! I wish I’d thought of that.”

Years from now, animators at the Mouseworks will be saying that very same thing when they come across Paul and Gaetan’s “Don Quixote” artwork. But do you know which conceptual art file Disney’s artists — top animators like Andreas Deja, even — request to see the most nowadays?

Would you believe it was for a Disney animated film that was to have featured fowl?

The Best Film Disney Never Made

Yep, nearly 40 years before Rocky and Ginger made their great escape in Dreamworks SKG / Aardman Animation’s “Chicken Run,” Disney proposed starring chickens in a feature length ‘toon. But these weren’t going to be common English hens. Walt was interested in exotic birds. Parisian poultry.

What was the name of this proposed film? “Chanticleer.” That name alone is enough to make animation historians sigh ruefully. Why for? Because this proposed animated film occupies a very unique spot in toon history. It may just be the best film Disney never made.

Source Material – “Chantecler” by Cyrano De Bergerac

What was the problem here? Well, to understand what went wrong with this proposed film, you have to go back to its source material: Edmond Rostand’s comedy, “Chantecler.” Edmond — best known today as the author of “Cyrano De Bergerac” — stitched together a slight story about a vain little rooster who thought that only his crowing could cause the sun to rise. Though it was set in a barnyard, “Chantecler” was actually a sly satire of pre-World War I French society bean. In spite of its satiric underpinnings (or maybe because of them) Rostand’s play became a favorite with European audiences — where it played to packed audiences for years.

“Chantecler” – 1937 Disney Project

Okay, now we jump to 1937. Walt Disney Studios is just about to finish work on their first feature length animated film, “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.” And Disney is casting about for ideas for the company’s next feature length cartoon when someone says “Hey, Walt. You ever hear of that play, ‘Chantecler’?”

Walt gets a quick run-down of Rostand’s plot and likes what he hears. He particularly thinks that the barnyard setting filled with farm animals will lend itself to lots of great gags for the movie. So Disney puts two of his top storymen — Ted Sears and Al Perkins — to work adapting the play to the animation format.

A few weeks later, Sears and Perkins get back to Walt with bad news. Try as they might, they can’t turn Rostand’s play into toon material. Ted and Al gripe that the pre-World War I satire will be too highbrow for American audiences. More importantly, they just can’t come up with a way to make the proposed film’s central character — the vain rooster, Chantecler — into a sympathetic character.

Walt then proposed folding the story of “Chantecler” in with another French fable the studio was toying with animating, “The Romance of Reynard.” This story — actually a collection of eleventh century European folk tales and poems — featured Reynard, a clever fox who was always tricking greedy nobles and peasants out of their ill-gotten gold. After all, what better way is there to make a vain rooster sympathetic than to give him a strong enemy? Someone like — say — a tricky fox?

So Disney’s story people took another whack at adapting “Chantecler” to the screen, this time using Reynard the Fox as the rooster’s enemy. (About this same time, folks at the Mouse House also americanized the name of the project. Which is how “Chantecler” became “Chanticleer”. Anyway …)

But even with the new villain on board, “Chanticleer” still wasn’t quite coming together. Sure, the barnyard setting and the farm animals featured in the story gave Disney’s artists plenty of funny stuff to work with. And they produced plenty of wonderful conceptual drawings for the proposed project. But — in the end — “Chanticleer”‘s story was still very weak and the main characters not terribly sympathetic. So, Walt reluctantly shelved the project.

“Chanticleer” Proposed Revivals

But — in the years ahead — Disney would periodically pull “Chanticleer” off the shelf and ask his artists to take another whack at the material. The project was revived no less than than three different times in the 1940s alone (1941, 1945 and 1947). In fact, many of the drawings done for the late 1940s version of the film provided inspiration for Disney’s 1973 animated feature, “Robin Hood” (Which — not-so-co-incidentally starred a clever fox that tricked greedy nobles out of their ill-gotten gold.)

Still, after all this effort, Disney had yet to turn “Chanticleer” into the makings of a successful animated feature. So — as the 1950s arrived — Walt decided to shelve the project for good (or so he thought). He then turned his attention to other more pressing projects — like Disneyland.

Marc Davis, Ken Anderson, and “Chanticleer”

Okay. Now we jump to early 1960. Ken Anderson and Marc Davis have just about finished work on “101 Dalmatians” and they’re excited. They know they’ve produced a film that really moved feature animation into the modern age. Both through its use of the Xerox process to transfer the animator’s drawings to cels as well as the film’s sketchy layout and design, “101 Dalmatians” is light years ahead of the studio’s previous feature, the stodgy “Sleeping Beauty.”

And the characters! Thanks to the Xerox process, the artistry and power of the lead animator’s original drawings really shines through now. That’s why Cruella seems so vibrant, so theatrical. That’s Marc Davis drawings in the almost raw you’re seeing up there on the screen there.

Marc was eager to build on the theatricality of Cruella. He wanted feature animation to next tackle a project that would allow Disney’s artists to really go for broke. Swing for the fences. Do something that would dazzle and entertain a modern audience.

So what did Marc have in mind? Davis — who was a huge fan of musical theater — wanted to do the animated equivalent of a big Broadway musical. Something with great songs and lots of colorful characters.

Does this sound familiar, kids? It should. Nearly 30 years later, Howard Ashman and Alan Menken actually pulled this off when they collaborated with Disney Feature Animation to create “The Little Mermaid.” That wildly successful 1988 film provided the template for all the animated projects that follow, “Beauty and the Beast,” “Aladdin,” et al. And here was Marc Davis — 28 years ahead of his time — trying to get Disney to do this very same thing. Life’s funny sometimes, isn’t it?

Anywho … So what does one base a big Broadway- style animated musical on? Well, Marc and Ken looked through all of the stories Disney currently had in development — but didn’t find anything that they liked. Which is how they ended up in the morgue … excuse me … “Animation Research Library” … looking at the studio’s abandoned projects.

That’s when Marc came across all the great concept art that had been previously done for “Chanticleer.” Looking over all these colorful drawings of chickens and Reynard the Fox, Davis had a brainstorm. He turned to Anderson and said “You know, I think we could really do something with this …”

But first they had to win Walt over to their idea.

Getting Walt’s Approval for “Chanticleer”

When Ken and Marc told Disney that they wanted to revive the “Chanticleer” feature idea, Walt was initially thrilled. After all, he’d been trying to make a movie made out of Rostand’s play for over 20 years at this point. But then Disney hesitated for a moment.

“What about the plot?,” Walt asked.

“No one’s ever been able to pull a decent cartoon out of this play yet. What are you two going that’s finally going to make this thing work?”

“Simple,” Marc said. “We’re not going to use the play. Ken and I aren’t even going to read the play. We’ll take the bare bones of the story and just make something up.”

It was a pretty audacious way to try and adapt a well-known story to the screen. But Disney loved the idea. (So much so that when the studio began working on a cartoon adaptation of “The Jungle Book,” Walt’s only advice to the story team — after tossing a copy of Rudyard Kipling’s book in the middle of the story conference room table — was to say “Here’s the novel. Now the first thing I want you to do is not read it.”)

Creating an Original Story for “Chanticleer”

So Ken and Marc holed up in an office at Disney Feature Animation for months, doing character sketches and playing with various story ideas. The first thing they did was abandon all the work that the studio had done previously on “Chanticleer.” Their hope was that — by getting a fresh start — they might be able to come up with something original: a light-on-its-feet satiric cartoon comedy. Something similar to Frank Loesser’s 1961 Broadway hit, “How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying” — a show that made a lot of clever, pointed jokes but never put them across in a mean spirited way.

Chanticleer – The Hero

The film’s hero had to be — obviously — Chanticleer, a well meaning but not terribly bright rooster. He — and all the other chickens that lived in his village — honestly did believe that the sun came up only because Chanticleer’s crowing awakened it every morning. The ladies of the village all swooned at the sight of the handsome young ***. The men in the village all wanted to be his best friend. (Think of Chanticleer as a kinder, gentler version of Gaston from “Beauty and the Beast.”)

In fact, Chanticleer is so well liked that the people of the village decide to elect him Mayor. Naturally, all that power goes to his somewhat empty head. So Chanticleer starts nagging the hens to produce more eggs … which — of course — annoyed the ladies.

Reynard – The Villain

Enter the villain: Reynard the Fox. A shady character in a battered top hat, Reynard has a pencil thin mustache and continental charm. But behind those smooth words and those heavily lidded eyes, this fox is nothing more than a slick con artist — always playing the angles, always on the make.

The Plot of “Chanticleer”

Quickly sizing up Chanticleer’s sleepy village as a fruit — ripe for the plucking, Reynard sweet-talks some of the ladies of the village just so he can learn the lay of the land. The fox quickly ascertains that the chickens are unhappy under the rooster’s stern leadership and that the hens long to have a little fun.

That’s all Reynard has to hear. He slips out of town, only to return the very next day with his dark carnival. Run entirely by creatures of the night (owls, bobcats, moles, etc.) and birds of prey (vultures), the villagers have never seen anything like it. So the chickens stay up all night — singing, dancing and playing games of chance. When morning comes, the hens are entirely too tired to lay any eggs.

Chanticleer views the chickens’ behavior as civil disobedience, as a direct challenge to his authority. So he orders Reynard and his carnival to leave the village at once. The fox responds by saying that he thinks it’s time for a change in leadership in town. That’s when Reynard then announces that he’s running for mayor of the village.

Alright. I know. This doesn’t exactly sound like an award winning plot. And truth be told, it actually gets sillier from this point in: Chanticleer gets suckered into a pre-dawn duel with a Spanish fighting ***. (The Spaniard — as it turns out — is secretly working for Reynard.) Chanticleer is so busy trying not to get killed in this fight that he doesn’t notice that the sun has risen without his crowing that morning.

After the fight, Chanticleer realizes that he’s been a complete ass. He doesn’t control the sun anymore than he can control the other chickens in his village. Yet — because of his sincerity and newly humble nature — the villagers find it in their hearts to forgive him.

Working together, Chanticleer and the rest of the chickens rid the town of Reynard and his dark carnival. From that point forward, Chanticleer becomes the kind, good-hearted, thoughtful leader that the villagers had always hoped he’d be. Every morning, he still crows — not to wake the sun, mind you. But to wake his friends so that they can begin yet another day in their beautiful little French town.

Character Designs and Concept Sketches

Yes. Again, I know. The story sounds silly. Far too thin to support a feature length film. But what you haven’t seen are all the great characters Marc and Ken came up with to people this odd little story. Marc drew literally hundreds of concept sketches which show beautiful French hens decked out in their turn-of-the-century finery. Each of the villagers has a hat, coat or cape. Wearing glasses or clutching canes, they stare up at you — with their bright eyes and wide smiles — out of the concept sketches and seem to scream: “Animate me!”

These stylized characters — with their wonderful period costumes and stylized comic design — would have actually helped Anderson and Davis pull “Chanticleer” off. For Marc and Ken were really hoping to do something ballsy, something original with this film. They envisioned “Chanticleer” as an animated equivalent of a French farce. Something so light on its feet and fiercely funny that you never notice the elephant sized holes in the plot.

Music and Score for “Chanticleer”

Music too would have played a huge part in this film. Marc actually planned for the entire introductory sequence of “Chanticleer” to be done in song. Characters would have entered, literally lugging scenery to help set the stage for the show. Much in the style of Howard Ashman and Alan Menken’s “Belle” opening number for “Beauty and the Beast,” the villagers would have sung about Chanticleer:

“… We love him so, ’cause he brings the sun up, you know …”

Disney to Get Out of the Animation Business

The ironic part of all this was — as Marc and Ken were laboring to create a film that would move Disney Feature Animation into the 1960s — Disney’s accountants were trying to convince Walt to stop making cartoons entirely.

I know that nowadays – when an animated feature can make way over $100 million – it must sound strange that the Walt Disney Company had ever considered getting out of the animation business. But it’s true, kids.

At the time (1960 / 1961), Disney had already produced some 17 feature length animated films. Roy tried to persuade Walt that these were more than enough toon titles to adequately stock the studio’s film library. Studies had shown that Walt Disney Productions could release a different cartoon classics (“Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” “Pinocchio,” “Cinderella,” et al) each year and still make a healthy profit off the old movies. So there was really no sense in the company wasting any additional moneys making new animated films.

Shut Down Animation and Create Walt Disney World – Roy’s Attempt

Walt at first strongly resisted this idea. But Roy knew just what cards to play. He had heard that his brother was toying with building another Disneyland somewhere in the United States. Roy also knew that this park — which was supposed to be at least ten times larger that the original Anaheim project — was going to be expensive.

“You’d have all the money you needed to get started on your new park,” the elder Disney suggested, “if you just shut down feature animation.”

Walt again hesitated. For this was truly a tempting offer. All the money he needed to get started on his second park. Plus the cash necessary to fund the project that Disney was really interested in in those days: audio animatronics. Never mind that old, two dimensional stuff in “101 Dalmatians” and “Sleeping Beauty.” The three dimensional animated figures that Wathel Rogers and the other guys at WED were working on — the birds, that Chinaman’s head — that was what really intrigued Walt back then.

Disney had always been a forward thinking guy. He may have loved nostalgia, but he was also eager to tackle new projects, try new things. Compared to audio animatronics, animation did seem kind of old fashioned. But did Walt really dare to shut down Disney Feature Animation?

For weeks, the younger Disney debated the idea with his elder brother, Roy. In the end, Walt just couldn’t bring himself to do it. Walt Disney Productions’ financial security had initially been built on the popularity of the company’s animated movies. To stop making these fine family films entirely would just send the wrong message to the entertainment industry. So it just didn’t seem prudent to totally pull the plug.

Walt Agrees to Scale Back Disney

But what Walt did agree to do was to try scaling back animation production at the studio. Instead of a new animated feature every two years (the pace the company had tried to meet throughout the 1950s), Disney agreed to let Roy reconfigure things so that a new toon would come out once every four years.

The trouble was the studio currently had two animated films in active development: Bill Peet’s adaptation of T. H. White’s Arthurian fantasy, “The Sword and the Stone” and Marc Davis and Ken Anderson’s “Chanticleer.” To meet Roy’s new animation business plan, one of these projects was going to have to be shut down.

Guess which movie hits the cutting room floor?

Cancelling “Chanticleer” – “Sword and the Stone” Moves Forward

Without Bill Peet, Marc Davis or Ken Anderson’s knowledge, Walt brought himself up to speed concerning the current status of both projects. He did this by slipping into the animation building after hours, going into Peet, Davis and Anderson’s offices after they’d gone home for the day and examining all the pre-production art they’d produced for “The Sword in the Stone” and “Chanticleer.

After reviewing all of the conceptual material, Disney quickly came to one conclusion: In spite of the film’s heavy reliance on magic, it looked like “The Sword in the Stone” would be the easier (read that as cheaper) of the two films to produce. It was strictly a numbers thing.

- “Sword”‘s cast was smaller and mostly human — which made its characters easier to draw.

- That film’s story — though episodic in nature — also seemed to have a bit more heart than “Chanticleer.” Wart, from “Sword”, was an underdog that an audience could care about, root for. Chanticleer was … well … a pompous, preening rooster who thought the sun only rose because he crowed every morning. This was not exactly a character that an audience could immediately be expected to warm up to.

- “Sword in the Stone” had no elaborate musical numbers to stage, nor would its characters need big name celebrities to successfully voice their parts.

The final decision seemed like a no brainer. Bill Peet’s “The Sword in the Stone” would be the safer (read this also as cheaper) of the two films to produce.

So Disney would have to pull the plug on “Chanticleer.”

Telling Davis and Anderson

Now came the tough part. Walt was fond of both Marc and Ken. He knew that these guys had labored for the better part of a year in their attempt to turn “Chanticleer” into an animated feature. But Disney just didn’t have the heart to tell them that all of their hard work was for naught, that their film wouldn’t be going into production.

In the end, Walt couldn’t bring himself to tell Davis and Anderson that “Chanticleer” was canceled. So he didn’t. He let a member of Roy’s staff — with a mumbled aside — do the dirty work for him.

The Last Pitch Meeting

Marc knew he was in trouble the moment he saw where Walt was sitting.

Normally — at pitch meetings like this — Disney liked to be down front, dead center. Walt wanted to be as close to the action as possible, ready to leap up and act out a funny bit of business or quickly point out where the project had gone off track.

But Walt wasn’t sitting down front for the “Chanticleer” meeting. He quietly took a seat at the back of the room and avoided all eye contact with Davis and Anderson. The seats in the front row? They were all taken by “Roy’s Boys” — executives who worked on the financial side of the studio.

Marc and Ken quickly exchanged worried glances. But then, gathering his courage, Davis stepped to the front of the room and began his pitch for the proposed animated film.

No sooner had the phrase: “The hero of our story is Chanticleer, a rooster…” left Marc’s lips when one of Roy’s boys muttered to his co-horts: “A chicken can’t be heroic.”

Then Marc knew. 30 seconds into his pitch, “Chanticleer” was already dead in the water. All of Davis’s wonderful character sketches. All of Ken’s beautifully rendered backgrounds. None of that stuff mattered. This movie was never going to get made.

Still Marc pressed on — hoping against hope that he could win this audience over to the idea of doing an all-animated Broadway style musical that starred a chicken. No dice. The people attending this pitch session were polite but indifferent. For they knew what Anderson and Davis didn’t: That Walt had already canceled “Chanticleer.” He just hadn’t gotten around to telling them yet.

When the session was over, those in attendance shuffled out silently — not saying a word.

That includes Walt. Especially Walt.

Fallout from the “Chanticleer” Pitch Session

A week went by and Davis nor Anderson heard nothing from nobody. They just sat in their offices, shell-shocked at how badly the “Chanticleer” pitch session had gone.

Ken’s colleagues at Feature Animation gave these two a wide berth, avoided these two veteran animators like the plague. No one wanted to be associated with a development team that had failed that miserably in a pitch session for a proposed animated feature.

Only Davis and Anderson knew that they hadn’t really failed. They were certain that “Chanticleer” — as they designed it — would have made a wonderful animated film. Sure, it would have cost a bit more to make, taken a lot longer than “Sword” to produce. But audiences would have loved the finished product.

Only this time around, there wasn’t going to be a finished product. For some reason, the accountants — not Walt — were now calling the shots at Walt Disney Studios. And that meant an ambitious, expensive animated feature like “Chanticleer” was never going to make it off the drawing board.

What hurt most was not hearing from Walt. Walt — the guy who’d so strongly encouraged them to take this approach with the material. Walt — the guy who’d seemed so eager to get a “Chanticleer” movie made. Walt — the guy who sat in the back of that pitch session and didn’t say a word.

For a week, Marc waited by the phone — hoping that his boss would call and explain what the hell was happening. Why Roy’s Boys were suddenly deciding which features Disney’s animators could and couldn’t make.

Finally, the phone did ring. And — yes — it was Walt. But there was no explanation. No apology. Just a job offer.

Davis Gets a Job Offer at WED – No Mention of “Chanticleer”

“Marc,” Walt said, “Those guys at WED aren’t very good at staging gags. People have been complaining that Disneyland’s shows have gotten kind of humorless. Do you think you could go over to Glendale and help them out?”

That was it. No “I’m sorry I let the accountants torpedo your film.” No “You and Ken did a really great job. It’s just not the right time to make this movie.” No “That was the best work you guys ever did. I’m truly sorry that we can’t make this movie.” Just “Could you go over to Glendale and help those guys out?”

So Marc — because of his strong sense of personal loyalty to Walt Disney — went over to WED and helped those guys out. And he never returned to Feature Animation.

But — In the 17 years he stayed in Glendale working at Imagineering –Davis helped create some of the greatest theme park attractions the Disney theme parks had ever seen: “The Jungle Cruise.” “The Enchanted Tiki Room.” “It’s a Small World.” “Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln.” “The Carousel of Progress.” “Pirates of the Caribbean.” “The Haunted Mansion.” “The Hall of Presidents.” “County Bear Jamboree.” “America Sings.”

All of them great shows. Each of them displaying that distinctive Marc Davis touch.

But Marc never entirely forgot about “Chanticleer.” It was — to borrow a tired phrase that almost every angler uses — “the big one that got away.” The great film that would have really put a cap on his career as a master animator.

Ah, well … It wasn’t meant to be, I guess.

“Chanticleer” Nods, Easter Eggs, and References

Mind you, this didn’t stop Davis from folding characters and concepts he created for “Chanticleer” into his work at WED. Take another look at those singing chickens in “America Sings.” Do they look familiar? They should. Those birds belting out “Down by the River Side” are modeled after the feathered French hens would who have played the chorus in “Chanticleer.”

And it wasn’t just Marc that kept trying to recycle pieces of this proposed film. His character sketches for the aborted 1960s version of “Chanticleer” were so good, they quickly become the stuff of legends around Disney Feature Animation. Artists would repeatedly go down to the morgue (Excuse me. “Animation Research Library”), pull out the full color, beautifully rendered drawings Marc made for the movie and just marvel at them.

These drawings were so good — in fact — that veteran Disney animator Mel Shaw pulled them out in 1981 to try and sell Disney management on the idea that it was finally time for the studio to make “Chanticleer.” Hoping to improve the proposed project’s chances, Shaw worked up a story treatment that stressed the rooster’s heroic qualities — making him “the most MACHO (chicken) in all of France.”

Mel also threw together an inspiring set of pastel and watercolor conceptual drawings as he tried to sell the studio on making his vision of the film. But the folks running Walt Disney Productions in the early 1980s were more cautious and conservative then “Roy’s Boys” were back in 1960. They quickly shot down the idea of the studio ever doing “Chanticleer” as a full length feature.

When word got out that Disney had once again rejected the idea of doing “Chanticleer” as an animated feature, one man rejoiced. That man’s name? Don Bluth.

Don Bluth and Aurora Productions

Two years earlier, Bluth had made a very public break from the animation operation at Walt Disney Productions. Tired of the heads of the studio constantly cutting corners, always going for the safer choices, Bluth — one of the most talented young animators Disney Studio had at the time — bailed out of Burbank. He left his cozy corporate nest, taking 15 or more of Disney’s top young animators with them.

These folks started a new animation studio, “Aurora Productions.” Their mission: to make great animated films like Walt used to do. Movies like “Pinocchio” and “Bambi.” With strong storylines and full animation. Not tired, half-hearted films like “Robin Hood” and “The Aristocats.”

“The Secret of Nimh”

Right out of the box, Aurora Productions did make a great animated film. Maybe you’ve seen it … “The Secret of Nimh?” This film has everything a hit movie should have: A solid, moving story with superb animation. Characters you care about. Big laughs. Great action sequences. A beautiful score.

Yep, “The Secret of Nimh” had everything that a hit film should … everything except an audience. In spite of receiving tremendous reviews, “Nimh” really didn’t do all that well at the box office and quickly faded from sight.

But still — buoyed by those great reviews (as well as those encouraging phone calls from Spielberg and Lucas) — Bluth remained hopeful. Maybe someday — if he played his cards right — Don might get his shot at turning “Chanticleer” into a great animated film.

“Chanticleer” becomes “Rock-a-Doodle”

For — during his 10 year long tenure at the Mouse House — Bluth too had been down to the morgue (Aw … forget it!) and seen Marc’s drawings. That’s why he knew that a truly fine animated film could be pulled out of Rostand’s barnyard comedy.

10 years later, Don did get his chance at turning “Chanticleer” into a feature length animated film. And while it would be nice to report that Bluth did want Disney couldn’t: turned this French satire into a successful cartoon … that’s not exactly what happened, kids.

What went wrong? Well, for starters, Bluth’s version of “Chanticleer” — entitled “Rock-a-Doodle” — moves the story to America and turns this French vain rooster into … well .. sort of a feathered Elvis.

Then there’s the problem with the villain. Bluth knew that if he borrowed Disney’s proposed antagonist — Reynard the Fox — that it would be too obvious where he had cribbed his original source material from. So Bluth opted to create an all new villain for his “Chanticleer” cartoon: the Grand Duke (voiced by Christopher Plummer), an owl who wanted Chanticleer out of the way so that the sun would never rise again and the world would be forever shrouded in darkness.

Alright, so that’s exactly not the greatest motivation for a movie villain. There’s still lots to like about Bluth’s “Rock-a-Doodle.” Mouse fans will be pleased to hear that old Disney favorites like Phil Harris and Sandy Duncan provide voices for characters in the film. And — as a sly tribute to the original author of “Chanticleer,” Edmund Rostand — Don named the little boy/cat who drives the action in the movie Edmund.

Box Office Indifference for “Rock-a-Doodle”

Unfortunately, audiences in April 1992 (when “Rock-a-Doodle” finally made its stateside debut) weren’t feeling as kindly toward Don Bluth as I did. They greeted the film with indifference. “Rock-a-Doodle” got lousy reviews, did terrible box office and quickly sank like a stone.

So — since Don Bluth Productions turned out such a mediocre “Chanticleer” movie — that’s the end of the story, right? No one will ever again attempt an animated version of Rostand’s play, correct?

Not necessarily.

Andreas Deja

Modern Disney master animator Andreas Deja remains a huge fan of Marc Davis’ conceptual work for “Chanticleer.” In Charles Solomon’s great book about Disney animated features that never quite made it off the drawing board, “The Disney That Never Was,” (Hyperion Press, 1995), Deja is quoted as saying:

Marc designed some of the best looking characters I’ve ever seen — these characters want to be moved and used.

Deja’s obsession with this material continues. In April 2000 — as part of the “Tribute to Marc Davis” that was held at the Samuel Goldwyn Theater in Hollywood — Andreas took a few moments to show the crowd some of Marc’s drawings from “Chanticleer.” As he looked up at the images on the screen, Deja remarked:

It’s kind of sad that this movie was never produced; the studio decided to do ‘Sword in the Stone’ instead. Which is also a very good movie, but wouldn’t it have been nice to see these characters come to life? Apparently, at that time, the studio felt — according to Marc — that it would be too difficult to develop sympathy for a chicken. I don’t think so. I have sympathy for these guys.

Andreas Deja

He added, while still looking up at the pictures, “One of these days, I’ll have to sit down and do a few pencil tests of these characters — just to see them move.”

Maybe one day Disney will put together a test that finally convinces the accountants who are running the Walt Disney Company that there’s a great film to be made from Marc Davis’ “Chanticleer” conceptual material.

Here’s hoping, anyway.

Want more behind-the-scenes Disney stories? Dive deeper into the magic with Fine Tooning podcast, where Jim Hill and Drew Taylor explore animation news and history. Listen now at Fine Tooning on Apple Podcasts. For exclusive bonus episodes and even more insider content, check out Disney Unpacked on Patreon.

Film & Movies

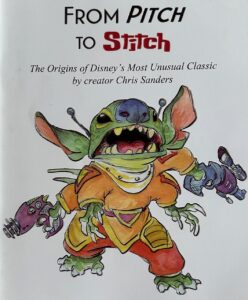

Before He Was 626: The Surprisingly Dark Origins of Disney’s Stitch

Hopes are high for Disney’s live-action version of Lilo & Stitch, which opens in theaters next week (on May 23rd to be exact). And – if current box office projections hold – it will sell more than $120 million worth of tickets in North America.

Stitch Before the Live-Action: What Fans Need to Know

But here’s the thing – there wouldn’t have been a hand-drawn version of Stitch to reimagine as a live-action film if it weren’t for Academy Award-winner Chris Sanders. Who – some 40 years ago – had a very different idea in mind for this project. Not an animated film or a live-action movie, for that matter. But – rather – a children’s picture book.

Sanders revealed the true origins of Lilo & Stitch in his self-published book, From Pitch to Stitch: The Origins of Disney’s Most Unusual Classic.

From Picture Book to Pitch Meeting

Chris – after he graduated from CalArts back in 1984 (this was three years before he began working for Disney) – landed a job at Marvel Comics. Which – because Marvel Animation was producing the Muppet Babies TV show – led to an opportunity to design characters for that animated series.

About a year into this gig (we’re now talking 1985), Sanders – in his time away from work – began noodling on a side project. As Chris recalled in From Pitch to Stitch:

“Early in my animation career, I tried writing a picture book that centered around a weird little creature that lived a solitary life in the forest. He was a monster, unsure of where he had come from, or where he belonged. I generated a concept drawing, wrote some pages and started making a sculpted version of him. But I soon abandoned it as the idea seemed too large and vague to fit in thirty pages or so.”

We now jump ahead 12 years or so. Sanders has quickly moved up through the ranks at Walt Disney Animation Studios. So much so that – by 1997 – Chris is now the Head of Story on Disney’s Mulan.

A Monster in the Forest Becomes Stitch on Earth

With Mulan deep in production, Sanders was looking for his next project when an opportunity came his way.

“I had dinner with Tom Schumacher, who was president of Feature Animation at the time. He asked if there was anything I might be interested in directing. After a little reflection, I realized that there was something: That old idea from a decade prior.”

When Sanders told Schumacher about the monster who lived alone in the forest…

“Tom offered the crucial observation that – because the animal world is already alien to us – I should consider relocating the creature to the human world.”

With that in mind, Chris dusted off the story and went to work.

Over the next three months, Sanders created a pitch book for the proposed animated film. What he came up with was very different from the version of Lilo & Stitch that eventually hit theaters in 2002.

The Most Dangerous Creature in the Known Universe

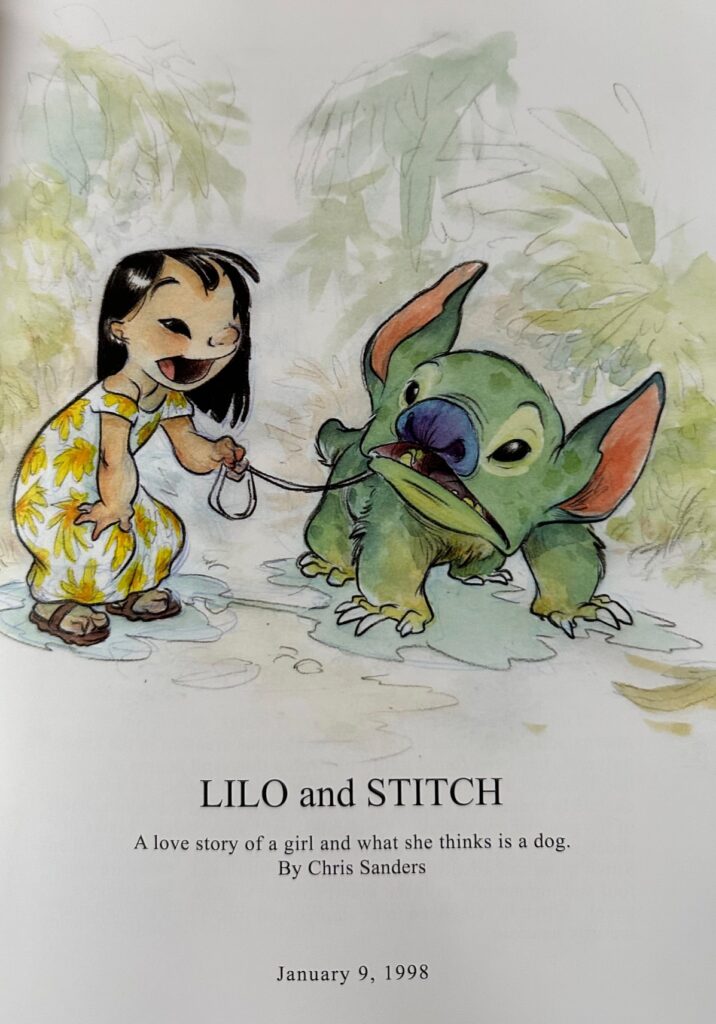

The pitch – first shared with Walt Disney Feature Animation staffers on January 9, 1998 – was titled: Lilo & Stitch: A love story of a girl and what she thinks is a dog.

This early version of Stitch was… not cute. Not cuddly. He was mean, selfish, self-centered – a career criminal. When the story opens, Stitch is in a security pod at an intergalactic trial, found guilty of 12,000 counts of hooliganism and attempted planetary enslavement.

Instead of being created by Jumba, Stitch leads a gang of marauders. His second-in-command? Ramthar, a giant, red shark-like brute.

When Stitch refuses to reveal the gang’s location, he’s sentenced to life on a maximum-security asteroid. But en route, his gang attacks the prison convoy. In the chaos, Stitch escapes in a hijacked pod and crash-lands on Earth.

Earth in Danger, Jumba on the Hunt

Terrified of what Stitch could do to our technologically inferior planet, the Grand Council Woman sends bounty hunter Jumba – along with a rule-abiding Cultural Contamination Control agent named Pleakley – to retrieve (or eliminate) Stitch.

Their mission must be secret, follow Earth laws, and – most importantly – ensure no harm comes to any humans.

Naturally, Stitch ignores all that.

After his crash, Stitch claws out of the wreckage, sees the lights of a nearby town, and screams, “I will destroy you all!” That plan is immediately derailed when he’s run over by a convoy of sugar cane trucks.

Waking up in the local humane society, Stitch sees a news report confirming the Federation is already hot on his trail. He needs to blend in. Fast.

Enter Lilo

Lilo is a lonely little girl, mourning her parents, looking for a pet. Stitch plays the role of a “cute little doggie” because it’s a means to an end. At this point, Lilo is just someone to use while he builds a communications device.

Using parts from her toys and a stolen police radio, Stitch contacts his old gang. But Ramthar, now the leader, isn’t thrilled. Still, Stitch sends a signal.

Then he builds an army.

Stitch Goes Full Skynet

Stitch constructs a small robot, sends it to the junkyard to build bigger robots. Soon, he has an army. When Ramthar and crew arrive, Stitch’s robots surround them. Ramthar is furious, but Stitch regains command.

Next, Stitch sets his robotic horde on a nearby town. Everything goes smoothly until a robot targets the hula studio where Lilo is dancing. As it lifts her in its claw, Stitch has a change of heart. He saves her.

From here, the plot begins to resemble the Lilo & Stitch we know today. Sort of.

The Ending That Never Was

In Sanders’ original version, it’s not Captain Gantu who kidnaps Lilo, but Ramthar. And when the Grand Council Woman comes to collect Stitch, Lilo produces a receipt from the humane society.

“I paid a $4 processing fee to adopt him. If you take Stitch, you’re stealing.”

The Grand Council Woman crumples the receipt and says, “I didn’t see it.”

Nani chimes in: “Well, I saw it.”

Then Jumba. Then one of Stitch’s old crew. Then a hula girl. And finally, Pleakley pulls out his CCC badge and says:

“Well, I am Pleakley Grathor, Cultural Contamination Control Agent No. 444. And I saw it.”

Pleakley saves Stitch.

How Roy E. Disney Made Stitch Cuddly

Ultimately, this version of Lilo & Stitch was streamlined. Roy E. Disney believed Stitch shouldn’t be nasty. Just naughty. And not by choice – he was designed that way.

Which is how Stitch became Experiment 626. A misunderstood creation of Jumba the mad scientist, not a hardened criminal with a vendetta.

The rest, as they say, is history.

Ricardo Montalbán’s Lost Role

Here’s a detail that even hardcore Lilo & Stitch fans may not know: Ricardo Montalbán—best known as Mr. Roarke from Fantasy Island and Khan Noonien Singh from Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan—was originally cast as the voice of Ramthar, Stitch’s second-in-command in this early version of the film. He had already recorded a significant amount of dialogue before the story was reworked following Roy E. Disney’s guidance. When Stitch evolved from a ruthless galactic outlaw to a misunderstood genetic experiment, Montalbán’s character (and much of the original gang concept) was written out entirely.

Which is kind of wild when you think about it. Wrath of Khan is widely considered the gold standard of Star Trek films. So yes, for a time, Khan himself was supposed to be part of Disney’s weirdest sci-fi comedy.

Stitch’s Legacy (and Why It Still Resonates)

Looking back at Stitch’s original story, it’s wild to think how close we came to getting a very different kind of movie. One where our favorite blue alien was less “ohana means family” and more “I’ll destroy you all.” But that transformation—from outlaw to outcast to ohana—is exactly what makes Lilo & Stitch so special.

So as the live-action version prepares to hit theaters, keep in mind that behind all the cuddly merch and tiki mugs lies one of Disney’s strangest, boldest, and most hard-won reinventions. One that started with a forest monster and became a beloved franchise about found family.

June 26th is officially Stitch Day—so mark your calendar. It’s a good excuse to celebrate just how far this little blue alien has come.

Film & Movies

How “An American Tail” Led to Disney’s “Hocus Pocus”

Over the last week, I’ve been delving into Witches Run Amok, Shannon Carlin’s oral history of the making of Disney’s Hocus Pocus. This book reveals some fascinating behind-the-scenes stories about the 1993 film that initially bombed at the box office but has since become a cult favorite, even spawning a sequel in 2022 that went on to become the most-watched release in Disney+ history.

But what really caught my eye in this 284-page hardcover wasn’t just the tales of Hocus Pocus’s unlikely rise to fame. Rather, it was the unexpected connections between Hocus Pocus and another beloved film—An American Tail. As it turns out, the two films share a curious origin story, one that begins in the mid-1980s, during the early days of the creative rebirth of Walt Disney Studios under Michael Eisner, Frank Wells, and Jeffrey Katzenberg.

The Birth of An American Tail

Let’s rewind to late 1984/early 1985, a period when Eisner, Wells, and Katzenberg were just getting settled at Disney and were on the hunt for fresh projects that would signal a new era at the studio. During this time, Katzenberg—tasked with revitalizing Disney Feature Animation—began meeting with talent across Hollywood, hoping to find a project that could breathe life into the struggling division.

One such meeting was with a 29-year-old writer and illustrator named David Kirschner. At the time, Kirschner’s biggest credit was illustrating children’s books featuring Muppets and Sesame Street characters, but he had an idea for a new project: a TV special about a mouse emigrating to America, culminating in the mouse’s arrival in New York Harbor on the same day as the dedication of the Statue of Liberty in 1886.

Katzenberg saw the patriotic appeal of the concept but ultimately passed on it, as he was focused on finding full-length feature projects for Disney’s animation department. Kirschner, undeterred, took his pitch elsewhere—to none other than Kathleen Kennedy, Steven Spielberg’s production partner. Kennedy was intrigued and invited Kirschner to Spielberg’s annual Fourth of July party to pitch the idea directly to the famed director.

Spielberg immediately saw the potential in Kirschner’s idea, but instead of a TV special, he envisioned a full-length animated feature film. This project would eventually become An American Tail, a tribute of sorts to Spielberg’s own grandfather, Philip Posner, who emigrated from Russia to the United States in the late 19th century. The film’s lead character, Fievel, was even named after Spielberg’s grandfather, whose Yiddish name was also Fievel.

Disney’s Loss Becomes Universal’s Gain

An American Tail went on to become a major success for Universal Pictures, which hadn’t been involved in an animated feature since the release of Pinocchio in Outer Space in 1965. Meanwhile, over at Disney, Eisner and Wells weren’t exactly thrilled that Katzenberg had let such a promising project slip through his fingers.

Not wanting to miss out on any future opportunities with Kirschner, Katzenberg quickly scheduled another meeting with him to discuss any other ideas he might have. And as fate would have it, Kirschner had just written a short story for Muppet Magazine called Halloween House, about a boy who is magically transformed into a cat by a trio of witches.

The Pitch That Sealed the Deal

Knowing Katzenberg could be a tough sell, Kirschner went all out to impress during his pitch. He requested access to the Disney lot 30 minutes early to set the stage for his presentation. When Katzenberg and the Disney development team walked into the conference room, they were greeted by a table covered in candy corn, a cauldron of dry ice fog, and a broom, mop, and vacuum cleaner suspended from the ceiling as if they were flying—evoking the magical world of Halloween House.

Katzenberg was reportedly unimpressed by the theatrical setup, muttering, “Oy, show-and-tell time” as he took his seat. But Kirschner knew exactly how to grab his attention. He started his pitch with the fact that Halloween was a billion-dollar business—a figure that made Katzenberg sit up and take notice. He listened attentively to Kirschner’s pitch, and by the time the meeting was over, Katzenberg was convinced. Halloween House would become Hocus Pocus, and Disney had its next big Halloween film.

A Bit of Hollywood Drama

Interestingly, Kirschner’s success with Hocus Pocus didn’t sit well with his old collaborators. About a year after the film’s release, Kirschner ran into Kathleen Kennedy at an Amblin holiday party, and she wasted no time in expressing her disappointment. According to Kirschner, Kennedy said, “You really hurt Steven.” When Kirschner asked how, she explained that Spielberg and Kennedy had given him his big break with An American Tail, but when he came up with the idea for his next film, he brought it to Disney rather than to them.

Hollywood can be a place where loyalty is valued—or, at least, perceived loyalty. At the same time, this was happening just as Katzenberg was leaving Disney and partnering with Spielberg and David Geffen to launch DreamWorks SKG, which only added to the tension. Loyalty, as Kirschner found out, can be an abstract concept in the entertainment industry.

A Halloween Favorite is Born

Despite its rocky start at the box office in 1993, Hocus Pocus has gone on to become a beloved part of Halloween pop culture. And, as Carlin’s book details, its success helped pave the way for more Disney Halloween-themed projects in the years that followed.

As for why Hocus Pocus was released in July of 1993 instead of during Halloween? That’s a story for another time, but it has something to do with another Halloween-themed project Disney was working on that year—Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas—and Katzenberg finding himself in the awkward position of having to choose between keeping Bette Midler or Tim Burton happy.

For more behind-the-scenes stories about Hocus Pocus and other Disney films, be sure to check out Witches Run Amok by Shannon Carlin. It’s a fascinating read for any Disney fan!

And if you love hearing these kinds of behind-the-scenes stories about animation and film history, be sure to check out Fine Tooning with Drew Taylor, where Drew and I dive deep into all things movies, animation, and the creative decisions that shape the films we love. You can find us on your favorite podcast platforms or right here on limegreen-loris-912771.hostingersite.com.

-

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment10 months ago

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment10 months agoDisney’s Forgotten Halloween Event: The Original Little Monsters on Main Street

-

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment10 months ago

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment10 months agoThe Story of Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party: From One Night to a Halloween Family Tradition

-

Film & Movies10 months ago

Film & Movies10 months agoHow “An American Tail” Led to Disney’s “Hocus Pocus”

-

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment8 months ago

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment8 months agoDisney and Macy’s 90-Year Thanksgiving Day Parade Partnership: From Mickey’s First Balloon to Minnie’s Big Debut

-

Television & Shows6 months ago

Television & Shows6 months agoHow the Creators of South Park Tricked A-List Celebrities to Roast Universal – “Your Studio & You”

-

History5 months ago