Film & Movies

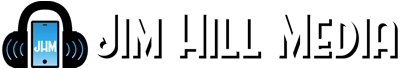

Be Careful What You Wish For – The Story of Robin Williams and Disney Films

In this April 2000 piece from the archives, Jim Hill exposes what really happened with comic genius Robin Williams and the Walt Disney Company's handling of the film "Aladdin" and looks at the tense relationship since.

Spring 1991: Robin Williams was suited up in green tights and hanging from a wire when he got the call.

It was then Disney Studio head Jeffrey Katzenberg on the line. Realizing that Robin was busy filming Steven Spielberg’s big budget Peter Pan update, Jeffrey apologized for the intrusion. But the Mouse had a real problem with an animated film they had in the works. So Katzenberg was wondering if Williams — who was well known in the industry as a big-time toon buff — might drop by Burbank and offer his opinion of the project.

Given that “Hook” was already running weeks behind schedule, Robin should have said “No.” But Williams had a soft spot when it came to the Mouse.

After all, Robin pretty much owed his film career in the 1990s to Disney.

“Good Morning Vietnam” & “The Dead Poets Society” – Early Robin Williams Disney Films

After starring in a string of cinematic stinkers like “Club Paradise” and “The Survivors,” Williams virtually couldn’t get arrested in Hollywood by the mid 1980s.

Then there was the very public collapse of his first marriage as well as rumors of drug and alcohol addiction.

Things were looking pretty bleak for the comic back then

But — in 1987 — Disney decided to take a chance on Robin. Figuring that the failures of his earlier films were due mainly to a poor marriage of performer and material, Disney sought to create a movie that would be a showcase for William’s gift for comic improvisation.

Katzenberg & Co. spent weeks looking for just the right piece of material for Robin. Finally — when Disney learned that Paramount Pictures had just put in to turnaround a script about an Armed Forces Network disc jockey and his adventures during the early days of the Vietnam War — Jeffrey knew that they had found the perfect vehicle for Williams. So the studio quickly snatched up the rights to “Good Morning, Vietnam.”

Williams — who was grateful for any opportunity to work at this point in his career — jumped at the chance to appear in this film. He even agreed to Disney’s less-than-generous financial terms, getting half of his usual $2 million paycheck to portray DJ Adrian Cronauer.

In the end, Disney’s gamble on Williams paid off handsomely. “Good Morning, Vietnam” proved to be a huge hit at the box office in the Winter of 1988. Both critics and audiences loved Robin’s performance. The role even earned him his first ever Academy Award nomination for best actor.

Disney decided to build on Williams’ success in “Good Morning, Vietnam” by starring the comic in another film for the studio, 1989’s “The Dead Poets Society.” Directed by noted Australian film-maker Peter Weir, this coming-of-age drama was also proved to be a huge hit with the movie-going public. Williams’ performance as devoted teacher John Keating earned Robin his second Oscar nomination as well as established him as a gifted dramatic actor.

Thanks to these two films, Robin Williams’ movie-making career came roaring back to life. All because Jeffrey Katzenberg had decided to take a chance on a semi-washed up comedian.

Which is why Robin Williams thought he would be forever grateful to the Mouse…

Or so he thought.

Saying Yes to “Aladdin” – Robin Williams Becomes the Genie

Anyhow, due to this sense of personal and professional obligation, Robin agreed to drop by Disney Studios on his very next day off from “Hook.” Less than a week later, Williams found himself in a meeting with Katzenberg as well as Disney animators John Musker, Ron Clements and Eric Goldberg.

Jeffrey thanked Robin for dropping by, then explained Disney’s dilemma: Feature Animation had just had one of its latest projects, a new musical version of “Aladdin,” spin into the dirt. The film’s screenwriter and lyricist Howard Ashman had tragically died from AIDS a month or so earlier. The “Aladdin” script Ashman had left behind had a lot of interesting things in it. But — structurally and story-wise — it was a mess.

Katzenberg then explained to Williams that the studio was thinking of junking Ashman’s screenplay. They’d hang on to most of Howard’s wonderful lyrics. But — beyond that — Disney was thinking of taking this animated musical in a whole new direction.

That said, Jeffrey directed Robin’s attention to a nearby TV monitor. There on the screen was an animated Robin Williams — doing a routine from his 1979 “Reality … What a Concept” album. The cartoon Williams announced that “Tonight, I’d like to talk to you about schizophrenia.” The toony Robin then grew a second head, which quickly told the first head to “Shut up! No he doesn’t!”

Williams was thoroughly charmed by the footage. Animator Goldberg — who had personally put together the test animation — had done a masterful job of transforming Robin’s comic genius into toon form. Turning back to Jeffrey, Williams then asked what it was that the Mouse wanted him to do now.

Katzenberg laid it on the line: We’d like you to join the cast of “Aladdin” as the voice of the Genie.

Williams hesitated for a moment. After all, the coming year was going to be one of his busiest ever, professionally. Once Robin finished playing Peter Pan in “Hook,” he’d leap right into work on “Toys.” This whimsical military satire set behind-the-scenes at a toy factory was a project that Williams was really looking forward to — for it would re-unite him with his “Good Morning, Vietnam” director, Barry Levinson. Between all the work he’d have to do to complete these two special effects-laden films, there just didn’t seem to be enough time to squeeze in an animated film for Disney.

But Jeffrey persisted. “Think of your son, Zachary,” Katzenberg said, “Or your daughter, Zelda. Wouldn’t they love to see their dad starring in a Disney animated film?”

That was the argument that finally won Williams over to doing “Aladdin.” Since so many of his earlier films had been rated R or PG, Robin’s children had yet to really see their daddy perform on the big screen. But here now was a movie that Williams could proudly take his kids to see on its opening day.

That was enough to win Robin over to the idea of doing the voice of the genie. However, this is not to say that Williams didn’t have a few conditions he wanted Disney to agree to before formally signing up to work on “Aladdin.”

Conditions for “Aladdin”: Robin’s Other Film -“Toys”

Chief among these conditions was Robin’s insistence that Disney Studio could not use his name or image in any theatrical posters, print ads, movie trailers or TV commercials to promote “Aladdin.

What was the deal here?

Was Robin pulling some sort of silly star trip on the Mouse?

No, not at all. It was just that Williams’ next live action film, “Toys,” and the animated “Aladdin” were due to be released within weeks of one another. “Aladdin” would roll into theaters over the 1992 Thanksgiving weekend, while “Toys” would be released in December.

Robin had agreed to do “Toys” first, so Williams felt that his primary loyalties had to lie with Levinson and his movie. Disney was free to promote “Aladdin” any way that they saw fit. Just so long as they didn’t create the impression that their animated film starred Robin Williams.

After all, the Genie was just a supporting role in “Aladdin.” So Robin asked that all ads for Disney’s film reflect that reality, and not give the false impression that the animated film somehow starred Williams’ character.

Jeffrey smiled and assured Robin that Disney Studios would be happy to meet his conditions.

However, the Mouse also had a few conditions of its own.

As much as Disney wanted Williams to play the voice of the Genie, the studio just wasn’t willing to pick up Robin’s now standard $8 million-per-picture paycheck. Since Disney would only be using Williams’ voice — which the Mouse could record in just a few quick studio sessions — in the movie, would Robin be willing to work for a significantly smaller fee?

Like — say, maybe — scale? Screen Actor Guild minimum. $485 a day.

Williams’ agent — the then all-powerful head of Creative Artist Associates (CAA) Michael Ovitz — thought the deal Disney was offering Robin was absurd. If the Mouse wasn’t willing to pay for Williams’ services up front, Ovitz insisted that the very least they could do was offer Robin a piece of the movie’s back end.

Williams told Ovitz to butt out. After all, he wasn’t making “Aladdin” to make money. Robin was making this movie so that Zachary and Zelda could see their daddy in a Disney movie.

“Besides,” Williams continued, “This is animated. How much money could the movie make, anyway?”

How Much Can an Animated Movie Make in the Early 90s?

From our position (current day), where a “Lion King” can earn a billion dollars at the box office plus a billion more off of toys, games, videos, etc. — Williams’ statement seems awfully naive. But please remember that Robin was talking to Ovitz back in the Spring of 1991. Disney’s latest animated film, 1990’s “The Rescuers Down Under,” had just under-performed at the box office. And while it was true that 1988’s “The Little Mermaid” had earned $80 million domestically, that film’s performance seemed more like a fluke than the start of a trend.

Williams had no idea that Disney’s “Beauty and the Beast” was lying out there in the bushes, getting ready to change forever the way people viewed animation. When that film hit theaters in November 1991, it racked up great reviews and huge box office numbers. By the spring of 1992, that movie would gross over $140 million as well as earn the first ever “Best Picture” nomination for a feature length animated film.

$140 million seemed like an extraordinary amount for an animated film to make. But “Aladdin” — with its $217 million gross — did better than “Beauty and the Beast.” And 1994’s “The Lion King” — with its $350 million — did even better than that.

But Williams had no idea that any of this was going to happen. He had no clue that animation was about to become really big money for the film industry. Robin just wanted to make a movie that he could take his kids to see.

But — more importantly — Williams wanted to pay Katzenberg & Co. back for all the kindness Disney had showed him in the mid-1980s. If the Mouse hadn’t taken a chance on him and “Good Morning, Vietnam,” Robin’s film career might still be on the skids. So, if the Walt Disney Company wanted to keep costs down on “Aladdin” by only paying him scale for his recording sessions, that was okay by Robin.

So Williams agreed to Katzenberg’s proposal — working for scale — provided, of course, that the studio honored Robin’s request to keep his names out of all the “Aladdin” ads.

“Hook”, “Toys”, and “Aladdin” – Robin Williams Busy Schedule

Robin kept his end of the bargain. Over the next 18 months, while working on “Hook” and “Toys,” Williams would slip away for a day or two every month for recording sessions on “Aladdin.” At each of these session, he’d start off with just straight readings of the scenes he was given from Terry Rossio and Ted Elliot’s screenplay. But — once those sequences were recorded — Robin would begin to ad-lib additional dialogue for each of these scenes.

Musker and Clements loved the material Williams was inventing for the Genie. So much so that they began reworking “Aladdin” so that the Genie went from a minor supporting role in the film to a part that was almost as big as the title character’s.

This is where things started to get difficult for Katzenberg. All the test screenings Disney Studio held for their still-in-production animated film showed that “Aladdin” was going to be a huge hit. Maybe even bigger than “Beauty and the Beast.”

But — when they polled the audience after each test screening as to who their favorite character in the film was — Disney found that the audience just loved the Genie. The very character that Jeffrey had promised Williams that the studio would do nothing to promote.

Now here was Katzenberg’s dilemma: How could he honor his agreement with Williams and not mention his name in any of the film’s ad, yet still somehow clue people in to the comic’s incredible vocal performance in the movie?

Using the Genie in the Promo Material for “Aladdin” – Robin Williams and Jeffrey Katzenberg Battle

A last minute re-negotiation of Disney’s deal with Williams made Katzenberg’s job somewhat easier. Jeffrey convinced Robin that — since the Genie was featured prominently in 25% of “Aladdin”‘s running length — the character should be featured in 25% of every movie trailer, print ad, TV commercial and lobby poster for the film. After getting Katzenberg’s assurance that all this revamped advertising would not give the audience the false impression that Williams’ character was the star of the movie, Robin okayed the change.

“Aladdin” Theatrical Poster

But — as soon as Williams got his first glance of the original theatrical poster for “Aladdin” — he immediately regretted changing the terms of his deal with Katzenberg. Sure, the Genie was only featured on 25% of the poster. But his big blue face was the largest image on the thing. His smiling mug towered over the film’s title, while infinitely smaller images of Aladdin and Jasmine riding their magic carpet appeared toward the bottom of the poster. While Williams’ name was nowhere to be found on the poster, it was clear to Robin that Disney was trying to get across the message that his character was the biggest thing in “Aladdin.”

Williams complained loudly to Katzenberg’s office about the imagery used in the “Aladdin” movie theater poster. Jeffrey apologized, but pointed out that he had honored the exact conditions of their deal. Robin’s name WAS nowhere to be seen on the poster. More importantly, the Genie’s image did only took up 25% of the surface space of the poster. Katzenberg had honored the language of their agreement, even if the poster’s imagery totally violated the spirit of their deal.

Fearing that featuring his character so prominently in the movie’s posters and ads would sink “Toys” chances at the box office, Williams asked that all the original “Aladdin” advertising material be recalled and new posters be issued. Katzenberg again said he was sorry, but there was no way that was going to happen. Disney had already spent millions launching “Aladdin.” Any changes in advertising imagery would just have to wait till the film’s secondary release, when the studio would create new ads and posters … maybe.

Robin was furious at the way he felt Jeffrey had mislead him in regard to the way Disney was advertising “Aladdin.” And this would not be the last time Williams and Katzenberg would clash over the way the studio chose to hype the the film.

The Genie on Posters at American Bus Shelters

Just after “Aladdin” opened, Williams was driving through downtown Los Angeles and was shocked to see that many of the city’s bus shelters featured huge blue posters of the Genie. No other characters from “Aladdin” were featured in these enormous public advertisements. Just the Genie.

When Williams called Katzenberg to complain about the bus shelter posters, Jeffrey apologized profusely. “Obviously, there must have been some sort of mix-up,” the then-Disney Studio head said. “I’ll have them removed immediately.”

So all 300 of the LA area “Aladdin” bus shelter posters were recalled and destroyed. It was only later that Williams learned that thousands of these huge blue Genie posters had been created and had been installed in bus shelters all over the country, where they remained up for the entire time “Aladdin” was in theaters. Only the big blue Genie bus shelter posters that were in areas where Williams was likely to see them had been removed.

This was typical of Katzenberg’s abuse of his “Aladdin” advertising agreement with Williams. Time and again, Jeffrey would pay lip service to Robin — saying that he was doing everything he could to make sure that Disney’s marketing department honored their deal concerning all aspects of the advertising on “Aladdin.” But, once that phone call was over, Katzenberg would then turn around and tell the studio’s marketing guys that they could do whatever they wanted to help promote the film.

“Toys” Disappointment

Just as Williams had feared, the Thanksgiving release of “Aladdin” totally over-shadowed the December release of “Toys.” Sure, this Barry Levinson film’s chances for success at the box office were hobbled by the vicious reviews this limp comedy received. But — had it been the only Robin Williams film in the marketplace that holiday season — “Toys” might have still done some business.

Unfortunately, for Christmas 1992, movie-goers had two Robin Williams films to chose from. 99.999% of the holiday audience opted to go see “Aladdin.” So “Toys” sank like a stone, barely taking in $23 million (which was less than half of the film’s production costs).

As “Toys” sank and “Aladdin” soared, Williams just didn’t know what to think.

On one hand, Robin was thrilled at “Aladdin”‘s amazing success.

Week after week, it was number 1 at the box office.

On the other hand, Robin felt incredibly guilty, thinking that Disney’s relentless advertising of “Aladdin” had snuffed out “Toys” (a film his friend Levinson had labored for 15 years to get made) only chances of ever finding an audience.

Then there was the performer’s ambivalence toward all the praise Williams was receiving for his work in “Aladdin.” Time and again, people would come up to Robin and tell him his performance in the animated film was his best thing he’d ever done. Initially, Williams enjoyed these compliments — until he realized that people were saying that his very best work was in a cartoon, a medium that only made use of an actor’s voice, not his face. This is the sort of thing that can really start to bug a guy who studied at Juilliard.

Awards and the Final Straw for the Genie

Williams’ ambivalence toward “Aladdin” became public knowledge in February 1993, when he received a certificate of special achievement for his work in the film at the Golden Globes. As he went up on the stage, the clearly uncomfortable Robin didn’t know what to say about this alleged honor. He jokingly asked the celebrities and foreign film critics assembled for the ceremony, “Is this like a coupon I can turn in to get a real award?”

Oddly enough, it was Disney’s attempt to capitalize on Williams’ win at the Golden Globes that proved to be the final breaking point between the Mouse and Mork. Katzenberg okayed a brand new series of print and TV ads for “Aladdin.” Each of these clearly mentioned Williams’ name, prominently playing up the award the Foreign Film Critics Association had honored the comic with.

As the then-head of Disney Studio, Jeffrey thought that he was just doing his job by okaying these ads. After all, the Golden Globes are considered by many in the film industry as a prelude to the Academy Awards. If Williams’ work as the Genie in “Aladdin” had been honored by the Foreign Film Critics Association, maybe the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences could also see their way clear to honoring Robin. Maybe they could even give him a special Oscar for the best vocal performance in an animated film. Hey, stranger things have happened.

However, when Williams saw these new ads, he finally blew his top. This was the last straw as far as the comic was concerned. Robin had deliberately asked Katzenberg to keep his name out of any “Aladdin” advertising. Now here was his name prominently displayed in ads throughout the trades as part of Disney’s Oscar campaign for the film.

Robin phoned Katzenberg and told the studio chief that he had repeatedly broken his word to the performer. As a result, Williams felt that he could no longer trust any executives associated with the Mouse Works. Robin then vowed that he would never again make another film for Walt Disney Studios.

Jeffrey Katzenberg Attempts to Win Over Robin Williams

Jeffrey — who was in the middle of orchestrating a million dollar ad campaign that would hopefully help “Aladdin” win a few Oscars — was horrified by what he called “Mork’s melt-down.” Sure, maybe Katzenberg had gone back on his word a few times concerning the film’s advertising. But couldn’t Robin see that Jeffrey had only done this because he had the movie’s best interests at heart? With a domestic gross of $217 million, “Aladdin” was then the highest grossing picture in the history of Walt Disney Studios. Wasn’t Williams thrilled to just to be a part of that enormous success?

Williams was not. In fact, Williams was beginning to feel like a really big schmuck for having agreed to work for scale on “Aladdin.” In addition, many of Robin’s friends in the industry began bad-mouthing the Mouse for not belatedly cutting Williams in on a chunk of the animated film’s enormous success. A very popular joke in Hollywood at the time went something like this:

Q: Why won’t the Mouse write Robin Williams a check for his work in “Aladdin”?

A: You try holding a pen with only four fingers.

Katzenberg tried to make amends with Williams by sending him a Picasso. Jeffrey made sure that word got out that Disney had spent over $5 million to purchase this belated “Thank You” gift for Robin. Imagine Katzenberg’s embarrassment when it later became common knowledge among industry insiders that the studio had picked up the painting at an estate sale for less than $750,000.

In spite of the lavish gift, Robin still refused to have anything to do with the Mouse. For years, he wouldn’t look at the scripts the studio sent him. He returned all invitations to the company’s premieres and/or theme park events. Things looked pretty hopeless…

Until Joe Roth replaced Jeffrey Katzenberg as the head of Disney Studios.

Joe Roth, Marcia Garces Williams, and “Mrs. Doubtfire”

Just like he used to have for Katzenberg & Co, Williams had a soft spot in his heart for Joe Roth.

Why for? Because — before going over to Disney in early 1992 to start up Caravan Pictures — Roth had been in charge of film production at 20th Century Fox. One of Joe’s last official acts as head of that studio was greenlighting production of Williams’ Christmas 1992 hit, “Mrs. Doubtfire.”

Why would this make Williams feel grateful toward Roth? Because “Mrs. Doubtfire” was the first film produced by Marcia Garces Williams — Robin’s wife. Marcia had long been the butt of many cruel jokes in Hollywood, given the unusual way her relationship with Robin began. (Garces had originally been hired by Robin’s first wife, Valerie, to act as a nanny to their son, Zachary. Williams and Garces had an affair that eventually led to the end of Robin’s marriage to Valerie. Garces then became Williams’ personal assistant before finally marrying the comic in 1989.) But “Mrs. Doubtfire” finally dispelled all those rumors about Marcia being Yoko to Robin’s John Lennon.

That film’s big box office gave Marcia huge credibility in Hollywood. All the cruel jokes ended — all because Joe Roth had greenlighted production of “Mrs. Doubtfire.”

Once Joe Roth took over production at Disney Studios, he learned that Francis Ford Coppola was readying a film, “Jack,” that would be perfect for Robin Williams to star in. So Joe had the script messengered to Williams’ home in Sonoma Valley.

Williams quickly returned the script, along with a note that explained that — while he would love to do a film with Coppola — he was no longer willing to work for the Mouse.

Joe then personally called Robin and asked why he didn’t want to work for Disney anymore. Williams went into a long involved explanation of how he felt he had been betrayed by Jeffrey Katzenberg.

Roth then pointed out that Katzenberg no longer worked for the Walt Disney Company. Robin went on to say that — since many of the people who had helped Jeffrey pull a fast one on the comic were still working for the Mouse — even with Katzenberg gone, Williams just didn’t feel comfortable coming back to for Disney.

But Joe wouldn’t give up. “What if the company publicly apologized to you?” he asked Robin.

Williams hadn’t expected something like that. And he was floored when Joe Roth then held a press conference in 1996, where the then-studio chief explained to the media how the Walt Disney Company had wronged Robin Williams. Roth then went on to offer a public apology for all wrongs previous company executives had committed against the comic.

Roth followed up on this press conference by taking out full page ads in many of the industry’s trade papers, explaining that the Walt Disney Company was sorry that it hadn’t honored its agreement with Robin Williams.

Robin was flabbergasted that Joe would go to all this trouble to try and right Katzenberg’s wrongs. He gladly accepted Roth’s apology as well as his invitation to come work at Disney on Francis Ford Coppola’s “Jack.”

Robin Williams Works for Disney Again

In fact, Williams was so thrilled at Joe’s efforts on his behalf that he even agreed to once again provide the voice for the Genie in a direct-to-video sequel to the original “Aladdin” movie, 1996’s “Aladdin and the King of Thieves.”

In turn, Disney was so thrilled to have Robin back as the Genie that they threw out all the recordings Dan Castellaneta (the Genie’s voice for the “Aladdin” TV show as well as the film’s first direct-to-video sequel, 1994’s “The Return of Jafar”) had already made as well as the third of the film that had already been animated.

With Williams once again on board, the animators started from scratch. All the extra effort proved to be worthwhile. Immediately upon release, “Aladdin and the King of Thieves” became the number 1 best selling video in the country.

Did Disney’s renewed relationship with Robin Williams last? Williams made two films for the Disney Company in 1997: a remake of Fred McMurray’s “Absent Minded Professor” comedy called “Flubber” that was Walt Disney Pictures’ big Thanksgiving weekend release for that year; as well as “Good Will Hunting,” a drama produced by the company’s art house subsidy, Miramax Pictures. Williams’ performance as the depressed therapist in that film actually earned him a “Best Supporting Actor” Oscar at the 1998 Academy Awards.

But there was some storm clouds. Williams is said to be upset at how Disney handled his last film for the company, 1999’s “Bicentennial Man.” First the studio announced the project with much fanfare — heralding it as the long awaited re-union between Robin and his “Mrs. Doubtfire” director, Chris (“Home Alone”) Columbus. Then, well after pre-production is underway, the Mouse abruptly canceled the movie, saying that the film’s projected production budget was too high.

Embarrassed by Disney’s behavior but still anxious to make the movie, Williams and Columbus shaved $20 million or so off the film’s production budget. With these cuts in place, Disney then agreed to put “Bicentennial Man” back into production. The film was finally released Christmas Day 1999 and quickly flopped.

Williams reportedly was upset with the way Disney opted to advertise the film as well as the financial restrictions the Mouse placed on Robin and Columbus while making the movie. The comic felt that the $20 million worth of scenes he and Chris cut out of the script to get the film greenlighted again may have destroyed the “Bicentennial Man”‘s chances of ever winning over an audience.

Equally troubling to Williams was Joe Roth’s decision to step down as head of Disney Studios. Who’s started running the show at the Mouse Works? One of Jeffrey Katzenberg’s former lieutenants from Disney Feature Animation, Peter Schneider.

Oh well. It was fun while it lasted.

Film & Movies

How “An American Tail” Led to Disney’s “Hocus Pocus”

Over the last week, I’ve been delving into Witches Run Amok, Shannon Carlin’s oral history of the making of Disney’s Hocus Pocus. This book reveals some fascinating behind-the-scenes stories about the 1993 film that initially bombed at the box office but has since become a cult favorite, even spawning a sequel in 2022 that went on to become the most-watched release in Disney+ history.

But what really caught my eye in this 284-page hardcover wasn’t just the tales of Hocus Pocus’s unlikely rise to fame. Rather, it was the unexpected connections between Hocus Pocus and another beloved film—An American Tail. As it turns out, the two films share a curious origin story, one that begins in the mid-1980s, during the early days of the creative rebirth of Walt Disney Studios under Michael Eisner, Frank Wells, and Jeffrey Katzenberg.

The Birth of An American Tail

Let’s rewind to late 1984/early 1985, a period when Eisner, Wells, and Katzenberg were just getting settled at Disney and were on the hunt for fresh projects that would signal a new era at the studio. During this time, Katzenberg—tasked with revitalizing Disney Feature Animation—began meeting with talent across Hollywood, hoping to find a project that could breathe life into the struggling division.

One such meeting was with a 29-year-old writer and illustrator named David Kirschner. At the time, Kirschner’s biggest credit was illustrating children’s books featuring Muppets and Sesame Street characters, but he had an idea for a new project: a TV special about a mouse emigrating to America, culminating in the mouse’s arrival in New York Harbor on the same day as the dedication of the Statue of Liberty in 1886.

Katzenberg saw the patriotic appeal of the concept but ultimately passed on it, as he was focused on finding full-length feature projects for Disney’s animation department. Kirschner, undeterred, took his pitch elsewhere—to none other than Kathleen Kennedy, Steven Spielberg’s production partner. Kennedy was intrigued and invited Kirschner to Spielberg’s annual Fourth of July party to pitch the idea directly to the famed director.

Spielberg immediately saw the potential in Kirschner’s idea, but instead of a TV special, he envisioned a full-length animated feature film. This project would eventually become An American Tail, a tribute of sorts to Spielberg’s own grandfather, Philip Posner, who emigrated from Russia to the United States in the late 19th century. The film’s lead character, Fievel, was even named after Spielberg’s grandfather, whose Yiddish name was also Fievel.

Disney’s Loss Becomes Universal’s Gain

An American Tail went on to become a major success for Universal Pictures, which hadn’t been involved in an animated feature since the release of Pinocchio in Outer Space in 1965. Meanwhile, over at Disney, Eisner and Wells weren’t exactly thrilled that Katzenberg had let such a promising project slip through his fingers.

Not wanting to miss out on any future opportunities with Kirschner, Katzenberg quickly scheduled another meeting with him to discuss any other ideas he might have. And as fate would have it, Kirschner had just written a short story for Muppet Magazine called Halloween House, about a boy who is magically transformed into a cat by a trio of witches.

The Pitch That Sealed the Deal

Knowing Katzenberg could be a tough sell, Kirschner went all out to impress during his pitch. He requested access to the Disney lot 30 minutes early to set the stage for his presentation. When Katzenberg and the Disney development team walked into the conference room, they were greeted by a table covered in candy corn, a cauldron of dry ice fog, and a broom, mop, and vacuum cleaner suspended from the ceiling as if they were flying—evoking the magical world of Halloween House.

Katzenberg was reportedly unimpressed by the theatrical setup, muttering, “Oy, show-and-tell time” as he took his seat. But Kirschner knew exactly how to grab his attention. He started his pitch with the fact that Halloween was a billion-dollar business—a figure that made Katzenberg sit up and take notice. He listened attentively to Kirschner’s pitch, and by the time the meeting was over, Katzenberg was convinced. Halloween House would become Hocus Pocus, and Disney had its next big Halloween film.

A Bit of Hollywood Drama

Interestingly, Kirschner’s success with Hocus Pocus didn’t sit well with his old collaborators. About a year after the film’s release, Kirschner ran into Kathleen Kennedy at an Amblin holiday party, and she wasted no time in expressing her disappointment. According to Kirschner, Kennedy said, “You really hurt Steven.” When Kirschner asked how, she explained that Spielberg and Kennedy had given him his big break with An American Tail, but when he came up with the idea for his next film, he brought it to Disney rather than to them.

Hollywood can be a place where loyalty is valued—or, at least, perceived loyalty. At the same time, this was happening just as Katzenberg was leaving Disney and partnering with Spielberg and David Geffen to launch DreamWorks SKG, which only added to the tension. Loyalty, as Kirschner found out, can be an abstract concept in the entertainment industry.

A Halloween Favorite is Born

Despite its rocky start at the box office in 1993, Hocus Pocus has gone on to become a beloved part of Halloween pop culture. And, as Carlin’s book details, its success helped pave the way for more Disney Halloween-themed projects in the years that followed.

As for why Hocus Pocus was released in July of 1993 instead of during Halloween? That’s a story for another time, but it has something to do with another Halloween-themed project Disney was working on that year—Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas—and Katzenberg finding himself in the awkward position of having to choose between keeping Bette Midler or Tim Burton happy.

For more behind-the-scenes stories about Hocus Pocus and other Disney films, be sure to check out Witches Run Amok by Shannon Carlin. It’s a fascinating read for any Disney fan!

And if you love hearing these kinds of behind-the-scenes stories about animation and film history, be sure to check out Fine Tooning with Drew Taylor, where Drew and I dive deep into all things movies, animation, and the creative decisions that shape the films we love. You can find us on your favorite podcast platforms or right here on JimHillMedia.com.

Film & Movies

How Disney’s “Bambi” led to the creation of Smokey Bear

When people talk about Disney’s “Bambi,” the scene that they typically cite as being the one from this 1942 film which then scarred them for life is – of course – the moment in this movie where Bambi’s mother gets shot by hunters.

Which is kind of ironic. Given that – if you watch this animated feature today – you’ll see that a lot of this ruined-my-childhood scene actually happens off-camera. I mean, you hear the rifle shot that takes down Bambi’s Mom. But you don’t actually see that Mama Deer get clipped.

Now for the scariest part of that movie that you actually see on-camera … Hands down, that has to be the forest fire sequence in “Bambi.” As the grown-up Bambi & his bride, Faline, desperately race through those woods, trying to find a path to safety as literally everything around them is ablaze … That sequence is literally nightmare fuel.

Mind you, the artists at Walt Disney Animation Studios had lots of inspiration for the forest fire sequence in “Bambi.” You see, in a typical year, the United States experiences – due to either natural phenomenon like lightning strikes or human carelessness – 100 forest fires. Whereas in 1940 (i.e., the year that Disney Studios began working in earnest of a movie version of Felix Salten’s best-selling movie), America found itself battling a record 360 forest fires.

Which greatly concerned the U.S. Forest Service. But not for the reason you might think.

Protecting the Forest for World War II

I mean, yes. Sure. Officials over in the Agricultural Department (That’s the arm of the U.S. government that manages the Forest Service) were obviously concerned about the impact that this record number of forest fires in 1940 had had on citizens. Not to mention all of the wildlife habitat that was now lost.

But to be honest, what really concerned government officials was those hundreds of thousands of acres of raw timber that had been consumed by these blazes. You see, by 1940, the world was on the cusp of the next world war. A conflict that the U.S. would inevitably be pulled into. And all that now-lost timber? It could have been used to fuel the U.S. war machine.

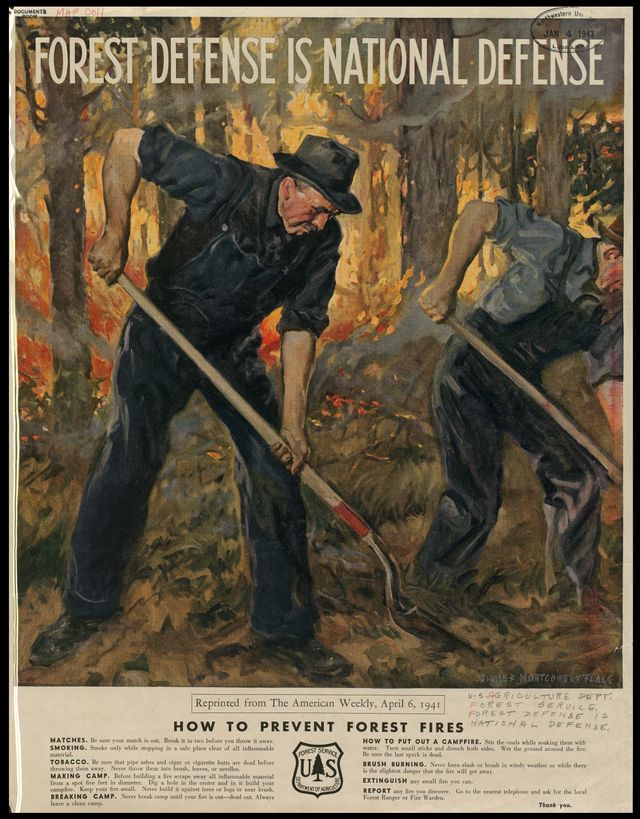

So with this in mind (and U.S. government officials now seeing an urgent need to preserve & protect this precious resource) … Which is why – in 1942 (just a few months after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor) – the U.S. Forest Service rolls out its first-ever forest fire prevention program.

Which – given that this was the early days of World War II – the slogan that the U.S. Forest Service initially chose for its forest fire prevention program is very in that era’s we’re-all-in-this-together / so-let’s-do-what-we-can-to-help-America’s war-effort esthetic – made a direct appeal to all those folks who were taking part in scrap metal drives: “Forest Defense is National Defense.”

And the poster that the U.S. Forest Service had created to support this campaign? … Well, it was well-meaning as well. It was done in the WPA style and showed men out in the forest, wielding shovels to ditch a ditch. They were trying to construct a fire break, which would then supposedly slow the forest fire that was directly behind them.

But the downside was … That “Forest Defense is National Defense” slogan – along with that poster which the U.S. Forest Service had created to support their new forest fire prevention program didn’t exactly capture America’s attention.

I mean, it was the War Years after all. A lot was going in the country at that time. But long story short: the U.S. Forest Service’s first attempt at launching a successful forest fire prevention program sank without a trace.

So what do you do in a situation like this? You regroup. You try something different.

Disney & Bambi to the Rescue

And within the U.S. government, the thinking now was “Well, what if we got a celebrity to serve as the spokesman for our new forest fire prevention program? Maybe that would then grab the public’s attention.”

The only problem was … Well, again, these are the War Years. And a lot of that era’s A-listers (people like Jimmy Stewart, Clark Gable, even Mel Brooks) had already enlisted. So there weren’t really a lot of big-name celebrities to choose from.

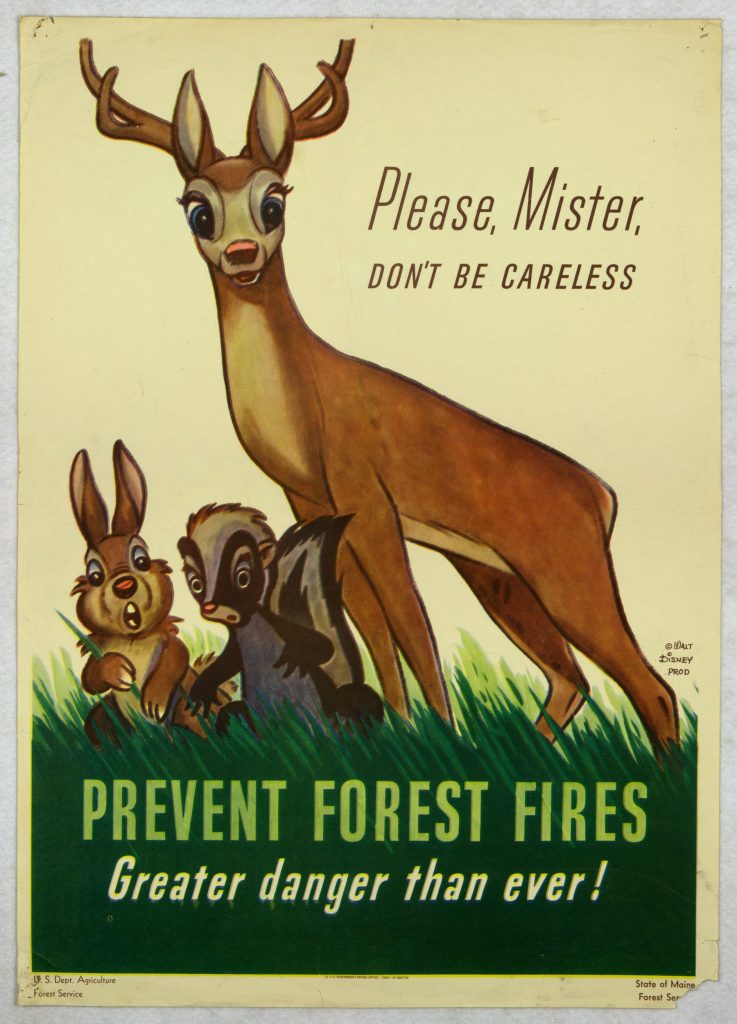

But then some enterprising official at the U.S. Forest Service came up with an interesting idea. He supposedly said “Hey, have you seen that new Disney movie? You know, the one with the deer? That movie has a forest fire in it. Maybe we should go talk with Walt Disney? Maybe he has some ideas about how we can better capture the public’s attention when it comes to our new forest fire prevention program?”

And it turns Walt did have an idea. Which was to use this government initiative as a way to cross-promote Disney Studio’s latest full-length animated feature, “Bambi.” Which been first released to theaters in August of 1942.

So Walt had artists at Disney Studio work up a poster that featured the grown-up versions of Bambi the Deer, Thumper the Rabbit & Flower the Skunk. As this trio stood in some tall grasses, they looked imploring out at whoever was standing in front of this poster. Above them was a piece of text that read “Please Mister, Don’t Be Careless.” And below these three cartoon characters was an additional line that read “Prevent Forest Fires. Greater Danger Than Ever!”

According to folks I’ve spoken with at Disney’s Corporate Archives, this “Bambi” -based promotional campaign for the U.S. Forest Service’s forest fire prevention campaign was a huge success. So much so that – as 1943 drew to a close – this division of the Department of Agriculture reportedly reached out to Walt to see if he’d be willing to let the U.S. Forest Service continue to use these cartoon characters to help raise the public’s awareness of fire safety.

Walt – for reasons known only to Mr. Disney – declined. Some have suggested that — because “Bambi” had actually lost money during its initial theatrical release in North America – that Walt was now looking to put that project behind him. And if there were posters plastered all over the place that then used the “Bambi” characters that then promoted the U.S.’s forest fire prevention efforts … Well, it would then be far harder for Mr. Disney to put this particular animated feature in the rear view mirror.

Introducing Smokey Bear

Long story short: Walt said “No” when it came to reusing the “Bambi” characters to promote the U.S. Forest Service’s forest fire prevention program. But given how successful the previous cartoon-based promotional campaign had been … Well, some enterprising employee at the Department of Agriculture reportedly said “Why don’t we come up with a cartoon character of our own?”

So – for the Summer of 1944 – the U.S. Forest Service (with the help of the Ad Council and the National Association of State Foresters) came up with a character to help promote the prevention of forest fires. And his name is Smokey Bear.

Now a lot of thought had gone into Smokey’s creation. Right from the get-go, it was decided that he would be an American black bear (NOT a brown bear or a grizzly). To make this character seem approachable, Smokey was outfitted with a ranger’s hat. He also wore a pair of blue jeans & carried a bucket.

As for his debut poster, Smokey was depicted as pouring water over a still-smoldering campfire. And below this cartoon character was printed Smokey’s initial catchphrase. Which was “Care will prevent 9 out of 10 forest fires!”

Which makes me think that this slogan was written by the very advertising executive who wrote “Four out of five dentists recommend sugarless gum for their patients who chew gum.”

Anyway … By the Summer of 1947, Smokey got a brand-new slogan. The one that he uses even today. Which is “Only YOU can prevent forest fires.”

The Real Smokey Bear

Now where this gets interesting is – in the Summer of 1950 – there was a terrible forest fire up in the Capitan Mountains of New Mexico. And over the course of this blaze, a bear cub climbed high up into a tree to try & escape those flames.

Firefighters were finally able to rescue that cub. But he was so badly injured in that fire that he was shipped off to the National Zoo in Washington, D.C. and nursed back to health. And since this bear really couldn’t be released back in the wild at this point, he was then put on exhibit.

And what does this bear’s keepers decide to call him? You guessed it: Smokey.

And due to all the news coverage that this orphaned bear got, he eventually became the living symbol of the U.S. Forest Service’s forest fire prevention program. Which then meant that this particular Smokey Bear got hit with a ton of fan mail. So much so that the National Zoo in Washington D.C. wound up with its own Zip Code.

“Smokey the Bear” Hit Song

And on the heels of a really-for-real Smokey Bear taking up residence in our nation’s capital, Steve Nelson & Jack Rollins decide to write a song that shined a spotlight on this fire-fightin’ bruin. Here’s the opening stanza:

With a ranger’s hat and shovel and a pair of dungarees,

You will find him in the forest always sniffin’ at the breeze,

People stop and pay attention when he tells them to beware

Because everybody knows that he’s the fire-preventin’ bear

Believe or not, even with lyrics like these, “Smokey the Bear” briefly topped the Country charts in the Summer of 1950. Thanks to a version of this song that was recorded by Gene Autry, the Singing Cowboy.

By the way, it was this song that started all of the confusion in regards to Smokey Bear’s now. You see, Nelson & Rollins – because they need the lyrics of their song to scan properly – opted to call this fire-fightin’-bruin Smokey THE Bear. Rather than Smokey Bear. Which has been this cartoon character’s official name since the U.S. Forest Service first introduced him back in 1944.

“The Ballad of Smokey the Bear”

Further complicating this issue was “The Ballad of Smokey the Bear,” which was a stop-motion animated special that debuted on NBC in late November of 1966. Produced by Rankin-Bass as a follow-up to their hugely popular “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” (which premiered on the Peacock Network in December of 1964) … This hour-long TV show also put a “THE” in the middle of Smokey Bear’s name because the folks at Rankin-Bass thought his name sounded better that way.

And speaking of animation … Disney’s “Bambi” made a brief return to the promotional campaign for the U.S. Forest Service’s forest fire prevention program in the late 1980s. This was because the Company’s home entertainment division had decided to release this full-length animated feature on VHS.

What’s kind of interesting, though, is the language used on the “Bambi” poster is a wee different than the language that’s used on Smokey’s poster. It reads “Protect Our Forest Friends. Only You Can Prevent Wildfires.” NOT “Forest Fires.”

Anyway, that’s how Disney’s “Bambi” led to the creation of Smokey Bear. Thanks for bearin’ with me as I clawed my way through this grizzly tale.

Film & Movies

“Indiana Jones and the Search for Indiana Jones”

News came late last week that NBC was cancelling the “Magnum PI” remake. This series (which obviously took its inspiration from the Tom Selleck show that originally debuted on CBS back in December of 1980 and then went on run on that network for 8 seasons. With its final episode airing on May 8, 1988).

Anyway … Over 30 years later, CBS decided to remake “Magnum.” This version of the action drama debuted on September 24, 2018 and ran for four seasons before then being cancelled. NBC picked up the “Magnum” remake where it ran for one more season before word came down on June 23rd that this action drama was being cancelled yet again.

FYI: The second half of Season 5 of “Magnum” (10 episodes) has yet to air on NBC. It will be interesting to see when that final set of shows / the series finale gets scheduled.

This all comes to mind this week – out ahead of the theatrical release of “Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny” because … Well, if CBS execs had been a bit more flexible back in 1980, the star of the original version of “Magnum PI” (Tom Selleck) would have played the lead in “Raiders of the Lost Ark.” Which was released to theaters back on June 12, 1981.

That’s the part of the Indiana Jones story that the folks at Lucasfilm often opt to skim over.

That Harrison Ford wasn’t George Lucas’ first choice to play Doctor Jones.

Auditions for Indiana Jones – Harrison’s Not on the List

Mind you, Steven Spielberg – right from the get-go – had pushed for Ford to play this part. The way I hear it, Lucas showed Spielberg a work-in-progress cut of “The Empire Strikes Back.” And Steven was so taken with Harrison’s performance as Han Solo in that Irwin Kershner film that he immediately began pushing for Ford to be cast as Doctor Jones.

Whereas Mr. Lucas … I mean, it wasn’t that George had anything against Harrison. What with Ford’s performances first in “American Grafitti” and then in “A New Hope,” these two already had a comfortable working relationship.

But that said, Lucas was genuinely leery of … Well, the sort of creative collaboration that Martin Scorcese and Robert DeNiro. Where one actor & one director repeatedly worked together. To George’s way of thinking, that was a risky path to follow. Hitching your wagon to a single star.

Which is why – when auditions got underway for “Raiders of the Lost Ark” in 1979 — Mike Fenton basically brought in every big performer of that era to read for Dr. Jones except Harrison Ford. We’re talking:

- Steve Martin

- Chevy Chase

- Bill Murray

- Jack Nicholson

- Peter Coyote

- Nick Nolte

- Sam Elliot

- Tim Matheson

- and Harry Hamlin

Casting a Comedian for Indiana Jones

Please note that there are a lot of comedians on this list. That’s because – while “Raiders of the Lost Ark” was in development — Spielberg was directed his epic WWII comedy, “1941.” And for a while there, Steve & George were genuinely uncertain about whether the movie that they were about to make would be a sincere valentine to the movie serials of the 1930s & the 1940s or more of a spoof.

It’s worth noting here that three of the more ridiculous set pieces found in “Temple of Doom” …

- the shoot-out at Club Obi Wan in Shanghai

- Indy, Willie & Short Round surviving that plane crash by throwing an inflatable life raft out of the cargo hatch

- and that film’s mine cart chase (which was not only inspired by Disney theme park favorites the Matterhorn Bobsleds & Big Thunder Mountain Railroad but some of the sound effects that you hear in this portion of “Temple of Doom” were actually recorded after hours at Disneyland inside of these very same attractions)

… all originally supposed to be in “Raiders of the Lost Ark.” I’ve actually got a copy of the very first version of the screenplay that Lawrence Kasdan wrote for the first “Indy” movie where all three of these big action set pieces were supposed to be part of the story that “Raiders” told. And I have to tell you that this early iteration of the “Raiders” screenplay really does read more like a spoof of serials than a sincere, loving salute to this specific style of cinema.

Casting Indiana Jones – Jeff or Tom

Anyway … Back now to the casting of the male lead for “Raiders” … After seeing virtually every actor out in LA while looking for just the right performer to portray Indiana Jones, it all came down to two guys:

- Jeff Bridges

- and Tom Selleck

Jeff Bridges as Indiana Jones

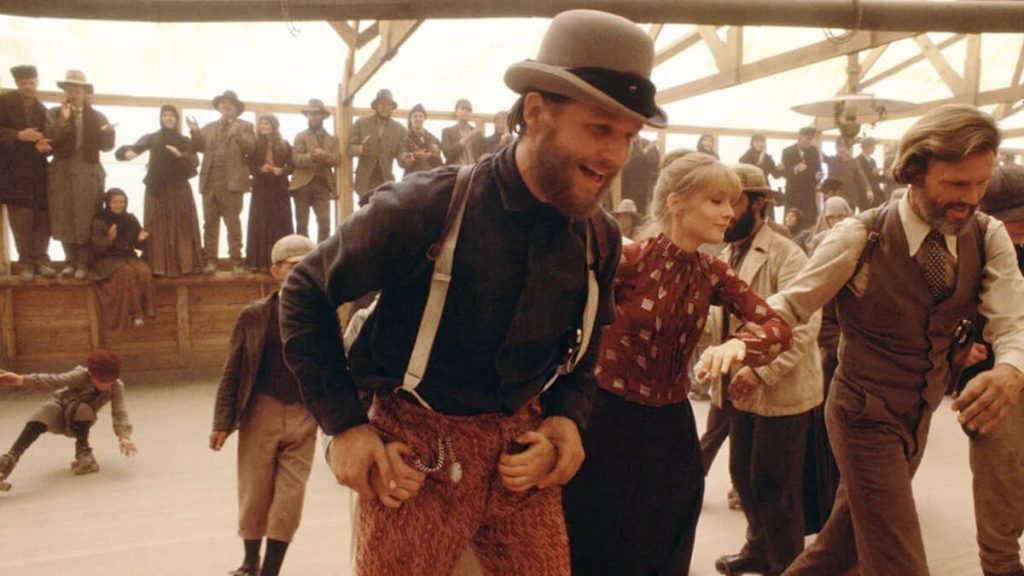

Mike Fenton was heavily pushing for Jeff Bridges. Having already appeared with Clint Eastwood in 1974’s “Thunderbolt & Lightfoot” (Not to mention that “King Kong” remake from 1976), Bridges was a known quantity. But what Fenton liked especially liked about Bridges when it came to “Raiders” was … Well, at that time, Jeff was just coming off “Heaven’s Gate.”

Mind you, nowadays, because we’ve all now had the luxury of seeing the director’s cut of this Michael Cimino movie, we recognize “Heaven’s Gate” for the cinematic masterpiece that it is. But 40+ years ago, that honestly wasn’t the case. All audiences had to judge this movie by was the severely truncated version that United Artists sent out into theaters. Which – because “Heaven’s Gate” had cost $44 million to make and only sold $3.5 million of tickets – then became the textbook example of Hollywood excess.

Long story short: Given that being associated with “Heaven’s Gate” had somewhat dinged Bridges’ reputation for being a marketable star (i.e., a performer that people would pay good money to see up on the big screen), Jeff was now looking to appear in something highly commercial. And the idea of playing the lead in a film directed by Steven Spielberg (the “Jaws” & “Close Encounter” guy) and produced by George Lucas (Mr. “Star Wars”) was very, very appealing at that time. Bridges was even willing to sign a contract with Spielberg & Lucas that would have then roped him into not only playing Indiana Jones in “Raider of the Lost Ark” but also to appear as this very same character in two yet-to-be-written sequels.

Better yet, because “Heaven’s Gate” had temporarily dimmed Bridges’ star status, Jeff was also willing to sign on to do the first “Indy” film for well below his usual quote. With the understanding that – should “Raiders of the Lost Ark” succeed at the box office – Bridges would then be paid far more to appear in this film’s two sequels.

That seemed like a very solid plan for “Raiders.” Landing a known movie star to play the lead in this action-adventure at a bargain price.

Ah, but standing in Mike Fenton’s way was Marcia Lucas.

Tom Selleck as Indiana Jones

Marcia Lucas, who had seen Tom Selleck’s audition for “Raiders” (And you can see it as well. Just go to Google and type in “Tom Selleck” and “Indiana Jones.” And if you dig around for a bit, you’ll then see a feature that Lucas & Spielberg shot for “Entertainment Tonight” back in 2008 [This story was done in support of the theatrical release of “Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull”]. And as part of this piece, George and Steve share Tom’s original audition for “Raiders.” And what’s genuinely fascinating about this footage is that Selleck’s scene partner is Sean Young. Who – at that time, anyway – was up for the role of Marion Ravenwood) and kept telling her husband, “You should cast this guy. He’s going to be a big star someday.”

And given that George was smart enough to regularly heed Marcia Lucas’ advice (She had made invaluable suggestions when it came to the editing of “American Graffiti” and the original “Star Wars.” Not to downplay George Lucas’ cinematic legacy, but Marcia Lucas was a world-class storyteller in and of her own right), Lucas then reached out to Spielberg and persuaded him that they should cast relative unknown Tom Selleck as Doctor Jones over the already well-known Jeff Bridges.

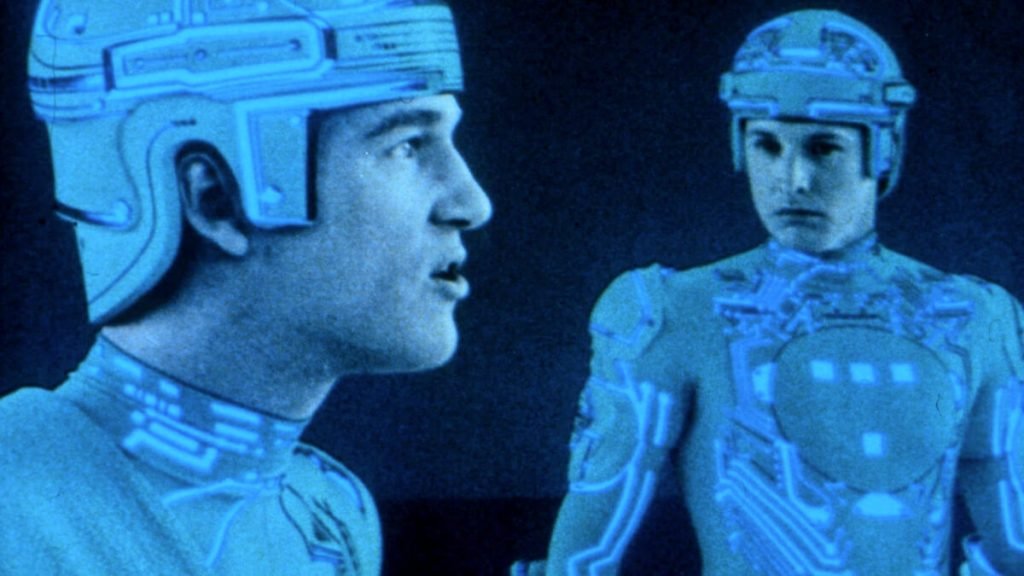

Now don’t feel too bad for Jeff Bridges. When he lost out on playing the lead in “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” Jeff then accepted a role in the very next, high profile, sure-to-be-commercial project that came along. Which turned out to be Disney’s very first “TRON” movie. Which was eventually released to theaters on July 9, 1982.

Back to Tom Selleck now … You have to remember that – back then – Selleck was the handsome guy who’d already shot pilots for six different shows that then hadn’t gone to series. Which was why Tom was stuck being the guest star on shows like “The Fall Guy” and “Taxi.” Whereas once word got out around town that Selleck was supposed to play the lead in a project that Spielberg was directed & Lucas was producing … Well, this is when CBS decided that they’d now take the most recent pilot that Tom had shot and then go to series with this show.

That program was – of course – the original “Magnum PI.” And it’s at this point where our story started to get complicated.

“Magnum PI” – Two Out of Three Say “Yes”

Okay. During the first season of a TV show, it’s traditionally the network – rather than the production company (which – in this case – was Glen A. Larson Productions. The company behind the original versions of “Battlestar Galactica” & “Knight Rider”) or the studio where this series is actually being shot (which – in this case – was Universal Television) that has all the power. And in this particular case, the network execs who were pulling all the strings behind-the-scenes worked for CBS.

And when it came to the first season of “Magnum PI,” CBS had a deal with Glen A. Larson Productions and Universal Television which stated that the talent which had been contracted to appear in this new action drama would then be available for the production of at least 13 episodes with an option to shoot an additional 9 episodes (This is known in the industry as the back nine. As in: the last nine holes of a golf course).

Anyway, if you take those initial 13 episodes and then tack on the back nine, you then get 22 episodes total. Which – back in the late 1970s / early 1980s, anyway – was what a full season of a network television show typically consisted of.

Anyway … The contract that Selleck had signed with Glen A. Larson Productions, Universal Television & CBS stated that he had to be available when production of Season One of “Magnum PI” began in March of 1980. More to the point, Tom also had to be available should CBS exercise its option to air 22 episodes of this new series on that television network over the course of “Magnum PI” ‘s first season.

Which then made things complicated for George Lucas & Steven Spielberg because … Well, in order for “Raiders of the Lost Ark” to make its June 12, 1981 release date, that then meant that production of the first “Indy” movie would have to get underway no later than June 23, 1980.

But here’s the thing: Production of Season One of “Magnum PI” was scheduled to run through the first week of July of that same year (1980). So in order for Tom Selleck to play Indiana Jones in “Raiders,” he was going to need to be wrapped on production of “Magnum PI” by June 22, 1980 at the absolute latest.

So Spielberg & Lucas went to Glen A. Larsons Productions and asked if Selleck could please be sprung from his “Magnum PI” contractual obligations by June 22nd. And they said “Yes.” Then Steven & George went to Universal Television and asked executives there for their help in clearing Tom’s schedule so that he’d then be available to start work on “Raiders.” And they say “Yes” as well.

Spielberg & Lucas now go to CBS. But instead of the quick “Yeses” that they got from officials at Glen A. Larson Productions and Universal Television, it takes those suits at the Tiffany Network weeks before they then decided to say “No, they couldn’t release Tom Selleck early to go work on ‘Raiders’ “ because …

I’ve never really been able to get a straight answer here as to why CBS execs dug in their heels here. Why they flat-out refused to release Selleck early from his “Magnum PI” contractual obligation and allow him to go shoot “Raiders.”

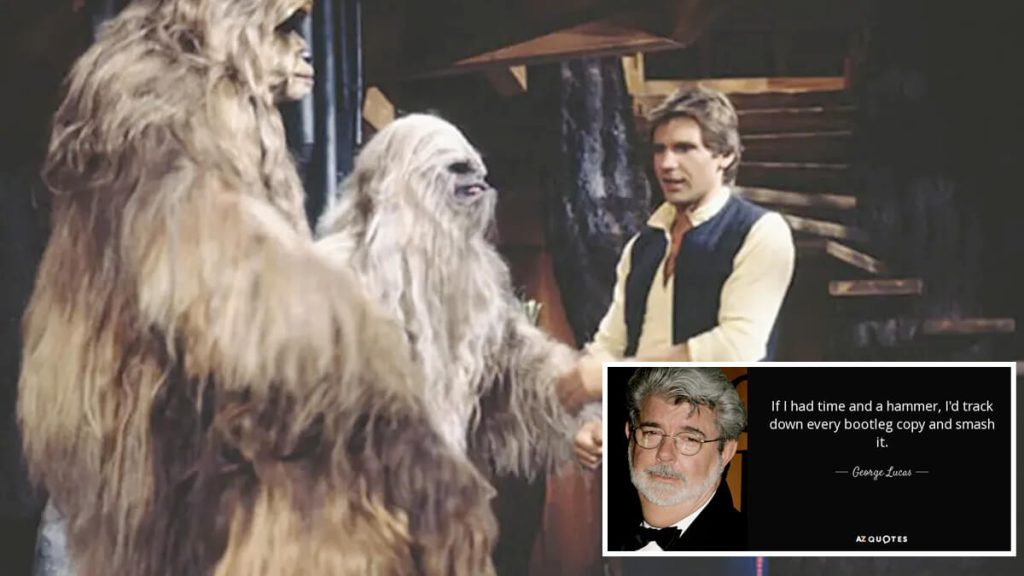

Payback from “The Star Wars Holiday Special” Trash Talk

That said, it is worth noting that “The Star Wars Holiday Special” aired on CBS back in November of 1978. And given that – in the years that followed — Lucas wasn’t exactly shy when it came to saying how much he hated that two hour-long presentation (Or – for that matter – how George really regretted caving into the requests of CBS execs. Who had insisted that television stars long associated with the Tiffany Network – people like Art Carney, Harvey Korman & Bea Arthur – be given prominent guest starring roles in “The Star Wars Holiday Special”). And I’ve heard whispers over the years that CBS executives preventing Tom Selleck from appearing in “Raiders” could be interpreted as the Tiffany Network getting some payback for what George had said publicly about the “Star Wars Holiday Special.”

Harrison Ford Comes to Rescue “Indiana Jones”

Anyway … It’s now literally just weeks before production of “Raiders of the Lost Ark” is supposed to begin and Spielberg & Lucas have just learned that that they’ve lost their film’s star. CBS is flat-out refusing to release Tom Selleck early from his “Magnum PI” contractual obligation. So Steven & George now have to find someone else to play Indy … and fast.

The real irony here is … The American Federation of Television and Radio Artists would go on strike in the Summer of 1980. Which then shut prematurely shut down production of the first season of “Magnum PI.” (As a direct result, the first full season of this action drama to air on CBS only had 18 episodes, rather than the usual 22). And because this job action lasted ‘til October 23rd of that same year … Well, this meant that Tom Selleck would have actually been free to start shooting “Raiders of the Lost Ark” on June 23, 1980 because production of Season One of “Magnum PI” was already shut down by then due to that AFTRA strike.

But no one knew – in May of 1980, anyway – that this job action was going to happen in just a few weeks. All that Steven Spielberg & George Lucas knew was that they now needed a new lead actor for “Raiders.” And circling back on Jeff Bridges was no longer an option. As I mentioned earlier, Jeff had agreed to do “TRON” for Disney. And – in the interim – Bridges gone off to shoot “Cutter’s Way” for MGM / UA.

So this is where Harrison Ford enters the equation. As he recalls:

In May of 1980, I get a call from George Lucas. Who says ‘I’m messaging a script over to you this morning. As soon as it gets there, I need you to immediately read this script. Then – as soon as you’re done – I need you to call.

So the script arrives and it’s for ‘Raiders.’ I read it and it’s good. So I call George back and say ‘It’s good.’ And he then says ‘Would you be interested in playing Indy?’ I say that it looks like it would be a fun part to play.

George then says ‘ That’s great to hear. Because we start shooting in four weeks. Now I need you to meet with Steven Spielberg today and convince him that you’re the right guy to play Indy.’

Of course, given that Spielberg had been pushing for Ford to pay Indy ever since he had first seen that work-in-progress version of “The Empire Strikes Back” … Well, Harrison’s meeting with Steven was very, very short. And just a few weeks later, Spielberg, Lucas & Ford were all at the Port de la Pallice in La Rochelle. Where – on the very first day of shooting on “Raiders” (which – again – was June 23, 1980)– the scene that was shot was the one where that Nazi sub (the one that Indy had lashed himself to its periscope by using his bullwhip as a rope) was arriving at its secret base.

And all of this happened because Harrison immediately agreed to do “Raiders of the Lost Ark” when the part of Indy was first offered to him in mid-May of 1980.

Before “Star Wars” was “Star Wars”

So why such a quick yes? Well, you have to remember that “Empire Strikes Back” wouldn’t be released to theaters ‘til May 21, 1980. And no one knew at that time whether this sequel to the original “Star Wars” would do as well at the box office as “A New Hope” had back in 1977 (FYI: “Empire” would eventually sell over $500 million worth of tickets worldwide. Which is roughly two thirds of what the original “Star Wars” earned three years earlier).

More to the point, the four films that Harrison had shot right after “A New Hope” / prior to “Empire Strikes Back” (i.e., “Heroes” AND “Force 10 from Navarone” AND “Hanover Street” AND “The Frisco Kid”) had all under-performed at the box office. So to Ford’s way of thinking, taking on a role that Tom Selleck was no longer available to play – one that had the potential of spawning two sequels – seemed like a very smart thing to do. Especially after three years of cinematic stumbles.

By the way, whenever this topic ever comes up, Harrison Ford is very gracious. He always makes a point of saying that he’s grateful to have gotten this career opportunity. More to the point, that he still feels kind of bad that Tom Selleck never got the chance to play this part.

Tom Selleck After “Indiana Jones”

That said, we shouldn’t feel too bad for Tom Selleck. After all, the original “Magnum PI” proved to be a long running hit for CBS. And in an effort to smooth over any residual bad feelings that may have resulted from Tom being forced to give up “Raiders” back in May of 1980, Selleck was eventually allowed to create his own production company (i.e., T.W.S. Productions, Inc. As in Thomas William Selleck Productions). Which – after the fact – was then cut in on some of those “Magnum PI” -related revenue streams.

More to the point, while “Magnum PI” was on hiatus following its second year in production, Selleck flew off to Yugoslavia. Where he then shot his own Indiana Jones-esque film for theatrical release. Which was called “High Road to China” in the States, but – overseas – was promoted as “Raiders of the End of the World.”

FYI: Warner Bros. released “High Road to China” stateside 40 years ago this year. On March 18, 1983, to be exact. It didn’t do all that great at the box office. $28 million in ticket sales versus $15 million in production costs.

And over the years, there’s even been some talk of finding a way to maybe set things right here. By that I mean: Finally finding a way to officially fold Tom Selleck into the world of Indiana Jones.

Could Tom Selleck Work with Indiana Jones?

The way I hear it, between the time when “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade” was theatrically released in May of 1989 and when “Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull” debuted in May of 2008, there were a number of ideas for Indiana Jones sequels tossed around. And from what I’ve been told, there was at least one treatment for a fourth Indiana Jones film written that proposed pairing up Harrison Ford & Tom Selleck. With the idea here being that Selleck was supposed to have played Ford’s brother.

Obviously that film was never made. And – no – I don’t know what state Indiana Jones’ brother was supposed to be named after.

This article is based on research for Looking at Lucasfilm “Episode 80”, published on June 29, 2023. Looking at Lucasfilm is part of the Jim Hill Media Podcast Network.

-

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment8 months ago

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment8 months agoDisney’s Forgotten Halloween Event: The Original Little Monsters on Main Street

-

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment8 months ago

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment8 months agoThe Story of Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party: From One Night to a Halloween Family Tradition

-

Film & Movies8 months ago

Film & Movies8 months agoHow “An American Tail” Led to Disney’s “Hocus Pocus”

-

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment6 months ago

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment6 months agoDisney and Macy’s 90-Year Thanksgiving Day Parade Partnership: From Mickey’s First Balloon to Minnie’s Big Debut

-

Television & Shows4 months ago

Television & Shows4 months agoHow the Creators of South Park Tricked A-List Celebrities to Roast Universal – “Your Studio & You”

-

History3 months ago

History3 months agoThe Super Bowl & Disney: The Untold Story Behind ‘I’m Going to Disneyland!’

-

Podcast1 month ago

Podcast1 month agoEpic Universal Podcast – Aztec Dancers, Mariachis, Tequila, and Ceremonial Sacrifices?! (Ep. 45)

-

Television & Shows3 weeks ago

Television & Shows3 weeks agoThe Untold Story of Super Soap Weekend at Disney-MGM Studios: How Daytime TV Took Over the Parks