Film & Movies

“Tale as Old as Time” may make you fall in love with Disney’s “Beauty and the Beast” all over again

It is arguably the best-loved film of that trio of fairy

tales that Walt Disney Animation Studios produced during its Second Golden Age.

The first hand-drawn animated feature ever to be nominated for Best Picture, "Beauty and the Beast" has been discussed, dissected and written about so often over

the past 19 years … Well, one has to wonder if there are any stories that have yet

to be told about this "Tale as old as Time."

Well, noted animation historian & critic Charles Solomon

rose to that challenge. He interviewed dozens of artists, executives and

animators who were personally involved with this much-beloved motion picture. And

given the nearly two decades that have passed at this point, a number of these

folks were now willing to share stories that reveal how truly troubled /

charmed this production was. Which is why Solomon's newest book, "Tale as Old as Time: The Art and Making of Beauty and the Beast" (Disney Editions, August

2010) now has be consider the definitive account of how this much-beloved

animated film actually came to be.

Copyright Disney Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved

And Charles, he goes all the way back. Back to the 1950s when Disney first

toyed with the idea of producing an animated version of this classic French fairy

tale. As Frank Thomas, one of the Studio's "Nine Old Men," once told Solomon:

"When Walt became all wrapped up in the theme parks and

live-action films, we tried to get him interested in animation again … (Disney)

said, "If I ever do go back, there are only two subjects I would want to do.

One of them is 'Beauty and the Beast.' For the life of me, I can't remember

what the other one was."

Charles then tried to determine whether any real development

was done on this project during Walt's day. But …

… neither the Walt Disney Archives nor the Animation

Research Library contain any artwork or story notes. Artists only began to

submit treatments for "Beauty and the Beast" years after Walt's death.

The earliest treatment was from Studio veterans Pete Young,

Vance Gerry, and Steve Hulett in 1983. In this version, the handsome prince of

a small but wealthy kingdom enjoys racing his carriage through the forest,

which scares the animals. The forest witch turns the prince into a "large,

furry, catlike creature" to teach him humility. Animals attend Belle in a

ruined castle, instead of enchanted objects.

Solomon then takes his readers through Disney's earliest

attempt at producing an animated version of "Beauty and the Beast." Back when

Richard and Jill Purdum, the husband-and-wife team, were in charge of this

project. Back when Maurice wasn't an inventor. But – rather – a kindly merchant

who had fallen on hard times …

Copyright Disney Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved

… and Belle had a younger sister, Clarice, as well as a cat

named Charley.

Copyright Disney Enterprises, inc. All rights reserved

But with the success of "The Little Mermaid," Jeffrey

Katzenberg (the then-head of Walt Disney Studios) decided that the Purdums'

far-too-dark, non-musical version wasn't going to work. As "Beauty and the

Beast" producer Don Hahn told Solomon:

(Katzenberg) said, "I want to get Howard (Ashman) and Alan

(Menken) involved and musicalize this. It has to be pushed, it has to be much

more entertaining, it has to be much more commercial. This is too dark. We've

got to start over."

And to make sure that this reboot of "Beauty and the Beast"

really did have a fresh new take on this material, Jeffrey handed this

production to two guys who had never ever directed a feature-length animated

film before, Kirk Wise and Gary Trousdale.

Which – as you might expect – led to a few clashes among

members of this newly-thrown-together creative team. Especially as they tried to get a handle on

how to properly tell this story. As Kirk Wise recalled one of his more

memorable encounters with Howard Ashman:

Finding a way to show how the Beast fell under the curse

provoked a memorable disagreement. Howard envisioned the prologue as a fully

animated sequence in which the audience would see a seven-year-old prince

rudely refuse to give shelter to an old woman during a storm. Revealing herself

to be a beautiful enchantress, the woman would chase the boy through the castle

hurling bolts of magic that would turn the servants into objects. Eventually

her spell would change the prince into the Beast boy, who would press his face

against one of the castle windows screaming "Come back! Come back!"

Copyright Disney Enterprises, Inc. All Rights Reserved

Gary and I hated the idea. The only thing that I could see

in my head was this Eddie Munster kid in a Little Lord Fauntleroy outfit," Kirk

recalls wincing. "I got elected to break the news that we had a different idea

for the prologue. Howard came in that morning all smiles, with a bag of

cinnamon-sugar donuts from his favorite shop. I can't remember what exactly I

said, but one of the words I used was cheap, meaning doing something terrible

to a child was a cheap way to pull an audience's heartstrings. I couldn't have

picked a worse word, because Howard just lit into me. We left for California

either that evening or the following morning, and because of the company's

austerity program, we were flying coach, with a layover in St. Louis. While we

were sitting on the runway, I thought, I could get off the plane, change my

name, and vanish into Missouri.

Copyright Disney Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved

But Wise didn't get off that plane and then sneak away into

the streets of St. Louis. He and Gary hung in there. Gradually growing in

confidence, thanks – in large part – to the talented vocal cast that they'd

assembled for "Beauty and the Beast."

You want to hear the textbook definition of "show business

professional" ? Check out this story that Solomon got Don Hahn to tell about

Angela Lansbury and the recording of the ballad for "Beauty and the Beast" :

(The) recording (of that) ballad was challenging … The

sessions were done at a studio in New York with a full orchestra and chorus;

Howard and Alan preferred to record a live performance rather than recording

the singer and the instrumental music separately.

"We booked Angela and her husband on MGM Grand Air out of

Los Angeles, but there was a bomb scare after they took off, and the plane had

to land in Las Vegas," said Don. "We finished recording 'Belle' and 'Be Our

Guest.' No Angela. Do we let the orchestra go and try and pick it up the next

day, or do we wait for Angela to call? Being the pro that she is, she called

from the airport: "I just landed, I'm on my way, I'll be there in a half hour."

Kirk Wise directs Angela Lansbury during a dialogue recording session for "Beauty

and the Beast." Copyright Disney Enterprises, inc. All rights reserved

When she arrived at the studio after a long and harrowing

day, Don told her, "You really don't have to do this. You can go home." He

says, "Angela said, 'Don't be ridiculous. I'm rehearsed. I'm ready to go." She

went into the booth and sang 'Beauty and the Beast' from beginning to end and

just nailed it. We picked up a couple of lines here and there, but essentially

that one take is what we used for the movie."

Of course, not everyone that Wise & Trousdale hired were

show business veterans like Lansbury. As Solomon reveals, the hunt for just the

right voice for the Beast led Kirk & Gary to make a very unlikely casting

choice:

The directors spent several worrisome weeks not knowing who

their leading man would be. One day, Albert (Tavares, "Beauty and the Beast" 's

casting director), brought in a tape that he reluctantly told Kirk and Gary was

from Robby Benson, an actor who was known at the time for playing earnest,

sensitive heroes.

Copyright Disney Enterprises, inc. All rights reserved

"We looked at him kind of cross-eyed and said 'Robby Benson?

Ice Castles Robby Benson?" Kirk recalls. "But his tape just blew us away. His

voice was an amazing combination of vulnerability and anger. The first time we

heard it, we said, 'I can hear the human being inside of the animal.' He

managed to play the animal side against the human side, and there was this

melancholic quality to his performance. He was finding layers that went well

beyond the actual dialogue. So we cut it against some visuals and played it for

Jeffery. He liked it, but when we told him who it was, he said the exact same

thing: "Ice Castles Robby Benson?"

And it's not just the casting of this film that Solomon

takes you behind-the-scenes with. Charles also reveals the role that Disney's finances

in the early 1990s played in the production of "Beauty and the Beast" :

When The Rescuers Down Under

was released in 1990 and earned

only $28 million domestically – only one third of the $84.3 million The Little

Mermaid made the year before – the filmmakers were required to pay more

attention to the bottom line.

"Rescuers kind of failed to live up to expectations, and the

watchword of the day became 'austerity.' It was a word we heard a lot," says

Kirk. "We had meetings to discuss every possible way to reduce the number of

man-hours it took to create each drawing. The biggest offender in that category

was Beast: Glen (Keane) had added six tiger stripes to the side of the Beast's head. They

looked great in the drawing, but they were absolute hell to clean up."

"We all came in one weekend to discuss ways to simplify the

movie so we could bring it in at a price that was palatable to the Studio but

wouldn't completely gut the production value. It wasn't easy and it wasn't

pleasant," he continues grimly. "At one point, Brian (McEntree) and Peter Schneider were

yelling at each other so loudly and turning so purple that Security knocked at

the door – they were worried that there was going to be some sort of incident."

Reading through this 176-page hardcover, you also learn

about the parts of "Beauty and the Beast" that didn't make it up on the big

screen. Not for budgetary reasons, mind you. But due to technological

challenges.

Copyright Disney Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved

Take – for example – the Beast's battle in the woods with

the wolves. As Solomon reveals in "Tale as Old as Time," this sequence in "Beauty

and the Beast" was originally supposed to be this CG tour-de-force:

When Chris Sanders storyboarded the chase through the forest

and the fight where the Beast defends Belle against the wolves, he wanted to

incorporate a moving camera that would follow Belle, Philippe, and the wolf

pack as they ran through the trees and across the snow. Kirk and Gary agreed

and asked the CG department if they could create a computer-generated forest

that would enable them to use the innovative photography they envisioned.

"They turned the idea over to our talented colleagues in CGI, and we waited.

Finally, after what seemed like months of research and development, they called

us in to see the progress they had made on the forest. We got this pointy,

wire-frame object that looked like a chicken's foot, which they could rotate in

space. I remember Don saying something to the effect of , 'That's it?' Not long

after that, we decided to pull the plug on the chicken-foot forest. We

concentrated the CG resources on creating the ballroom.

Copyright Disney Enterprises, inc. All rights reserved

Which isn't to say that that sequence was a hit straight out

of the box. When the original version of "Beauty and the Beast" 's CGI fly-thru

of the ballroom was shown to Katzenberg.

The camera moves were so fast and complicated it felt as if

the viewer were flying a jet fighter around the ballroom. (CG artist Greg

Griffith said): Jeffery was just apoplectic: 'This is not about Beauty and the

Beast.' This is not about these characters. This is not about anything except

you, showing off all the neat-o things you can do. Go back and do it again!' "

That's what's really great about "Tales as Old of Time."

This Charles Solomon book lets you see "Beauty and the Beast" as it really is.

Which Don Hahn likens to Dumbo:

Dumbo's my favorite Disney movie – along with many others –

but it's full of mistakes and bad drawings and such because they did it for a

price. We did this one for a price. There was a recession in 1991, and we were

scrambling: the whole movie got done in about eleven months."

"The odd thing is, it's not the best drawn movie. Aladdin

is

probably the best in terms of draftsmanship and design," he concludes

thoughtfully. "It's not the best-painted movie. It's probably not the best

musical score, although it does have the best songs in the world. But there's a

lot of youthful energy in the movie: this generation (of Disney artists and

animators) was in the sweet spot of their career when it was made. There's a

raw puppy love in Beauty and the Beast; you can only fall in love for the first

time once, and Beauty and the Beast was it."

Copyright Disney Enterprises, Inc.

All rights reserved

Well, I don't know about that. As you read through Charles

Solomon's "Tale as Old as Time: The Art and Making of Beauty and the Beast,"

you'll definitely come away with a renewed appreciation for this acclaimed animated

feature. Which is why – as you read through this new Disney Editions book – you

may find yourself falling in love with "Beauty and the Beast" all over again.

Your thoughts?

Film & Movies

Before He Was 626: The Surprisingly Dark Origins of Disney’s Stitch

Hopes are high for Disney’s live-action version of Lilo & Stitch, which opens in theaters next week (on May 23rd to be exact). And – if current box office projections hold – it will sell more than $120 million worth of tickets in North America.

Stitch Before the Live-Action: What Fans Need to Know

But here’s the thing – there wouldn’t have been a hand-drawn version of Stitch to reimagine as a live-action film if it weren’t for Academy Award-winner Chris Sanders. Who – some 40 years ago – had a very different idea in mind for this project. Not an animated film or a live-action movie, for that matter. But – rather – a children’s picture book.

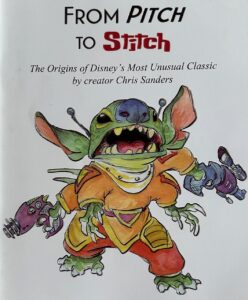

Sanders revealed the true origins of Lilo & Stitch in his self-published book, From Pitch to Stitch: The Origins of Disney’s Most Unusual Classic.

From Picture Book to Pitch Meeting

Chris – after he graduated from CalArts back in 1984 (this was three years before he began working for Disney) – landed a job at Marvel Comics. Which – because Marvel Animation was producing the Muppet Babies TV show – led to an opportunity to design characters for that animated series.

About a year into this gig (we’re now talking 1985), Sanders – in his time away from work – began noodling on a side project. As Chris recalled in From Pitch to Stitch:

“Early in my animation career, I tried writing a picture book that centered around a weird little creature that lived a solitary life in the forest. He was a monster, unsure of where he had come from, or where he belonged. I generated a concept drawing, wrote some pages and started making a sculpted version of him. But I soon abandoned it as the idea seemed too large and vague to fit in thirty pages or so.”

We now jump ahead 12 years or so. Sanders has quickly moved up through the ranks at Walt Disney Animation Studios. So much so that – by 1997 – Chris is now the Head of Story on Disney’s Mulan.

A Monster in the Forest Becomes Stitch on Earth

With Mulan deep in production, Sanders was looking for his next project when an opportunity came his way.

“I had dinner with Tom Schumacher, who was president of Feature Animation at the time. He asked if there was anything I might be interested in directing. After a little reflection, I realized that there was something: That old idea from a decade prior.”

When Sanders told Schumacher about the monster who lived alone in the forest…

“Tom offered the crucial observation that – because the animal world is already alien to us – I should consider relocating the creature to the human world.”

With that in mind, Chris dusted off the story and went to work.

Over the next three months, Sanders created a pitch book for the proposed animated film. What he came up with was very different from the version of Lilo & Stitch that eventually hit theaters in 2002.

The Most Dangerous Creature in the Known Universe

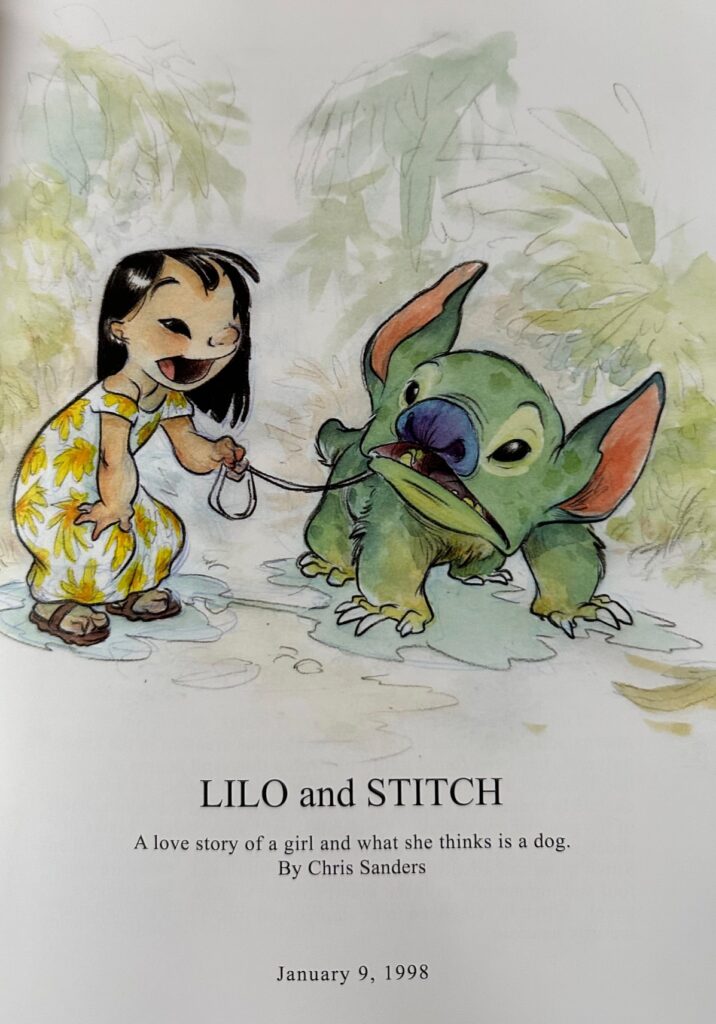

The pitch – first shared with Walt Disney Feature Animation staffers on January 9, 1998 – was titled: Lilo & Stitch: A love story of a girl and what she thinks is a dog.

This early version of Stitch was… not cute. Not cuddly. He was mean, selfish, self-centered – a career criminal. When the story opens, Stitch is in a security pod at an intergalactic trial, found guilty of 12,000 counts of hooliganism and attempted planetary enslavement.

Instead of being created by Jumba, Stitch leads a gang of marauders. His second-in-command? Ramthar, a giant, red shark-like brute.

When Stitch refuses to reveal the gang’s location, he’s sentenced to life on a maximum-security asteroid. But en route, his gang attacks the prison convoy. In the chaos, Stitch escapes in a hijacked pod and crash-lands on Earth.

Earth in Danger, Jumba on the Hunt

Terrified of what Stitch could do to our technologically inferior planet, the Grand Council Woman sends bounty hunter Jumba – along with a rule-abiding Cultural Contamination Control agent named Pleakley – to retrieve (or eliminate) Stitch.

Their mission must be secret, follow Earth laws, and – most importantly – ensure no harm comes to any humans.

Naturally, Stitch ignores all that.

After his crash, Stitch claws out of the wreckage, sees the lights of a nearby town, and screams, “I will destroy you all!” That plan is immediately derailed when he’s run over by a convoy of sugar cane trucks.

Waking up in the local humane society, Stitch sees a news report confirming the Federation is already hot on his trail. He needs to blend in. Fast.

Enter Lilo

Lilo is a lonely little girl, mourning her parents, looking for a pet. Stitch plays the role of a “cute little doggie” because it’s a means to an end. At this point, Lilo is just someone to use while he builds a communications device.

Using parts from her toys and a stolen police radio, Stitch contacts his old gang. But Ramthar, now the leader, isn’t thrilled. Still, Stitch sends a signal.

Then he builds an army.

Stitch Goes Full Skynet

Stitch constructs a small robot, sends it to the junkyard to build bigger robots. Soon, he has an army. When Ramthar and crew arrive, Stitch’s robots surround them. Ramthar is furious, but Stitch regains command.

Next, Stitch sets his robotic horde on a nearby town. Everything goes smoothly until a robot targets the hula studio where Lilo is dancing. As it lifts her in its claw, Stitch has a change of heart. He saves her.

From here, the plot begins to resemble the Lilo & Stitch we know today. Sort of.

The Ending That Never Was

In Sanders’ original version, it’s not Captain Gantu who kidnaps Lilo, but Ramthar. And when the Grand Council Woman comes to collect Stitch, Lilo produces a receipt from the humane society.

“I paid a $4 processing fee to adopt him. If you take Stitch, you’re stealing.”

The Grand Council Woman crumples the receipt and says, “I didn’t see it.”

Nani chimes in: “Well, I saw it.”

Then Jumba. Then one of Stitch’s old crew. Then a hula girl. And finally, Pleakley pulls out his CCC badge and says:

“Well, I am Pleakley Grathor, Cultural Contamination Control Agent No. 444. And I saw it.”

Pleakley saves Stitch.

How Roy E. Disney Made Stitch Cuddly

Ultimately, this version of Lilo & Stitch was streamlined. Roy E. Disney believed Stitch shouldn’t be nasty. Just naughty. And not by choice – he was designed that way.

Which is how Stitch became Experiment 626. A misunderstood creation of Jumba the mad scientist, not a hardened criminal with a vendetta.

The rest, as they say, is history.

Ricardo Montalbán’s Lost Role

Here’s a detail that even hardcore Lilo & Stitch fans may not know: Ricardo Montalbán—best known as Mr. Roarke from Fantasy Island and Khan Noonien Singh from Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan—was originally cast as the voice of Ramthar, Stitch’s second-in-command in this early version of the film. He had already recorded a significant amount of dialogue before the story was reworked following Roy E. Disney’s guidance. When Stitch evolved from a ruthless galactic outlaw to a misunderstood genetic experiment, Montalbán’s character (and much of the original gang concept) was written out entirely.

Which is kind of wild when you think about it. Wrath of Khan is widely considered the gold standard of Star Trek films. So yes, for a time, Khan himself was supposed to be part of Disney’s weirdest sci-fi comedy.

Stitch’s Legacy (and Why It Still Resonates)

Looking back at Stitch’s original story, it’s wild to think how close we came to getting a very different kind of movie. One where our favorite blue alien was less “ohana means family” and more “I’ll destroy you all.” But that transformation—from outlaw to outcast to ohana—is exactly what makes Lilo & Stitch so special.

So as the live-action version prepares to hit theaters, keep in mind that behind all the cuddly merch and tiki mugs lies one of Disney’s strangest, boldest, and most hard-won reinventions. One that started with a forest monster and became a beloved franchise about found family.

June 26th is officially Stitch Day—so mark your calendar. It’s a good excuse to celebrate just how far this little blue alien has come.

Film & Movies

How “An American Tail” Led to Disney’s “Hocus Pocus”

Over the last week, I’ve been delving into Witches Run Amok, Shannon Carlin’s oral history of the making of Disney’s Hocus Pocus. This book reveals some fascinating behind-the-scenes stories about the 1993 film that initially bombed at the box office but has since become a cult favorite, even spawning a sequel in 2022 that went on to become the most-watched release in Disney+ history.

But what really caught my eye in this 284-page hardcover wasn’t just the tales of Hocus Pocus’s unlikely rise to fame. Rather, it was the unexpected connections between Hocus Pocus and another beloved film—An American Tail. As it turns out, the two films share a curious origin story, one that begins in the mid-1980s, during the early days of the creative rebirth of Walt Disney Studios under Michael Eisner, Frank Wells, and Jeffrey Katzenberg.

The Birth of An American Tail

Let’s rewind to late 1984/early 1985, a period when Eisner, Wells, and Katzenberg were just getting settled at Disney and were on the hunt for fresh projects that would signal a new era at the studio. During this time, Katzenberg—tasked with revitalizing Disney Feature Animation—began meeting with talent across Hollywood, hoping to find a project that could breathe life into the struggling division.

One such meeting was with a 29-year-old writer and illustrator named David Kirschner. At the time, Kirschner’s biggest credit was illustrating children’s books featuring Muppets and Sesame Street characters, but he had an idea for a new project: a TV special about a mouse emigrating to America, culminating in the mouse’s arrival in New York Harbor on the same day as the dedication of the Statue of Liberty in 1886.

Katzenberg saw the patriotic appeal of the concept but ultimately passed on it, as he was focused on finding full-length feature projects for Disney’s animation department. Kirschner, undeterred, took his pitch elsewhere—to none other than Kathleen Kennedy, Steven Spielberg’s production partner. Kennedy was intrigued and invited Kirschner to Spielberg’s annual Fourth of July party to pitch the idea directly to the famed director.

Spielberg immediately saw the potential in Kirschner’s idea, but instead of a TV special, he envisioned a full-length animated feature film. This project would eventually become An American Tail, a tribute of sorts to Spielberg’s own grandfather, Philip Posner, who emigrated from Russia to the United States in the late 19th century. The film’s lead character, Fievel, was even named after Spielberg’s grandfather, whose Yiddish name was also Fievel.

Disney’s Loss Becomes Universal’s Gain

An American Tail went on to become a major success for Universal Pictures, which hadn’t been involved in an animated feature since the release of Pinocchio in Outer Space in 1965. Meanwhile, over at Disney, Eisner and Wells weren’t exactly thrilled that Katzenberg had let such a promising project slip through his fingers.

Not wanting to miss out on any future opportunities with Kirschner, Katzenberg quickly scheduled another meeting with him to discuss any other ideas he might have. And as fate would have it, Kirschner had just written a short story for Muppet Magazine called Halloween House, about a boy who is magically transformed into a cat by a trio of witches.

The Pitch That Sealed the Deal

Knowing Katzenberg could be a tough sell, Kirschner went all out to impress during his pitch. He requested access to the Disney lot 30 minutes early to set the stage for his presentation. When Katzenberg and the Disney development team walked into the conference room, they were greeted by a table covered in candy corn, a cauldron of dry ice fog, and a broom, mop, and vacuum cleaner suspended from the ceiling as if they were flying—evoking the magical world of Halloween House.

Katzenberg was reportedly unimpressed by the theatrical setup, muttering, “Oy, show-and-tell time” as he took his seat. But Kirschner knew exactly how to grab his attention. He started his pitch with the fact that Halloween was a billion-dollar business—a figure that made Katzenberg sit up and take notice. He listened attentively to Kirschner’s pitch, and by the time the meeting was over, Katzenberg was convinced. Halloween House would become Hocus Pocus, and Disney had its next big Halloween film.

A Bit of Hollywood Drama

Interestingly, Kirschner’s success with Hocus Pocus didn’t sit well with his old collaborators. About a year after the film’s release, Kirschner ran into Kathleen Kennedy at an Amblin holiday party, and she wasted no time in expressing her disappointment. According to Kirschner, Kennedy said, “You really hurt Steven.” When Kirschner asked how, she explained that Spielberg and Kennedy had given him his big break with An American Tail, but when he came up with the idea for his next film, he brought it to Disney rather than to them.

Hollywood can be a place where loyalty is valued—or, at least, perceived loyalty. At the same time, this was happening just as Katzenberg was leaving Disney and partnering with Spielberg and David Geffen to launch DreamWorks SKG, which only added to the tension. Loyalty, as Kirschner found out, can be an abstract concept in the entertainment industry.

A Halloween Favorite is Born

Despite its rocky start at the box office in 1993, Hocus Pocus has gone on to become a beloved part of Halloween pop culture. And, as Carlin’s book details, its success helped pave the way for more Disney Halloween-themed projects in the years that followed.

As for why Hocus Pocus was released in July of 1993 instead of during Halloween? That’s a story for another time, but it has something to do with another Halloween-themed project Disney was working on that year—Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas—and Katzenberg finding himself in the awkward position of having to choose between keeping Bette Midler or Tim Burton happy.

For more behind-the-scenes stories about Hocus Pocus and other Disney films, be sure to check out Witches Run Amok by Shannon Carlin. It’s a fascinating read for any Disney fan!

And if you love hearing these kinds of behind-the-scenes stories about animation and film history, be sure to check out Fine Tooning with Drew Taylor, where Drew and I dive deep into all things movies, animation, and the creative decisions that shape the films we love. You can find us on your favorite podcast platforms or right here on limegreen-loris-912771.hostingersite.com.

Film & Movies

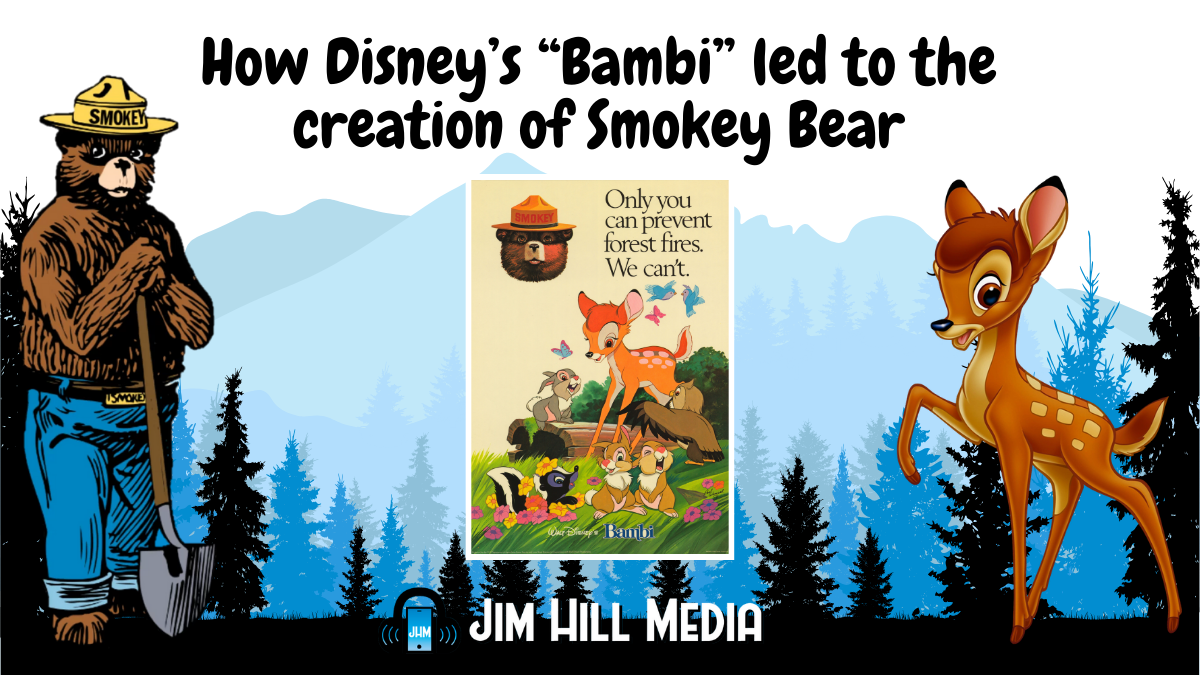

How Disney’s “Bambi” led to the creation of Smokey Bear

When people talk about Disney’s “Bambi,” the scene that they typically cite as being the one from this 1942 film which then scarred them for life is – of course – the moment in this movie where Bambi’s mother gets shot by hunters.

Which is kind of ironic. Given that – if you watch this animated feature today – you’ll see that a lot of this ruined-my-childhood scene actually happens off-camera. I mean, you hear the rifle shot that takes down Bambi’s Mom. But you don’t actually see that Mama Deer get clipped.

Now for the scariest part of that movie that you actually see on-camera … Hands down, that has to be the forest fire sequence in “Bambi.” As the grown-up Bambi & his bride, Faline, desperately race through those woods, trying to find a path to safety as literally everything around them is ablaze … That sequence is literally nightmare fuel.

Mind you, the artists at Walt Disney Animation Studios had lots of inspiration for the forest fire sequence in “Bambi.” You see, in a typical year, the United States experiences – due to either natural phenomenon like lightning strikes or human carelessness – 100 forest fires. Whereas in 1940 (i.e., the year that Disney Studios began working in earnest of a movie version of Felix Salten’s best-selling movie), America found itself battling a record 360 forest fires.

Which greatly concerned the U.S. Forest Service. But not for the reason you might think.

Protecting the Forest for World War II

I mean, yes. Sure. Officials over in the Agricultural Department (That’s the arm of the U.S. government that manages the Forest Service) were obviously concerned about the impact that this record number of forest fires in 1940 had had on citizens. Not to mention all of the wildlife habitat that was now lost.

But to be honest, what really concerned government officials was those hundreds of thousands of acres of raw timber that had been consumed by these blazes. You see, by 1940, the world was on the cusp of the next world war. A conflict that the U.S. would inevitably be pulled into. And all that now-lost timber? It could have been used to fuel the U.S. war machine.

So with this in mind (and U.S. government officials now seeing an urgent need to preserve & protect this precious resource) … Which is why – in 1942 (just a few months after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor) – the U.S. Forest Service rolls out its first-ever forest fire prevention program.

Which – given that this was the early days of World War II – the slogan that the U.S. Forest Service initially chose for its forest fire prevention program is very in that era’s we’re-all-in-this-together / so-let’s-do-what-we-can-to-help-America’s war-effort esthetic – made a direct appeal to all those folks who were taking part in scrap metal drives: “Forest Defense is National Defense.”

And the poster that the U.S. Forest Service had created to support this campaign? … Well, it was well-meaning as well. It was done in the WPA style and showed men out in the forest, wielding shovels to ditch a ditch. They were trying to construct a fire break, which would then supposedly slow the forest fire that was directly behind them.

But the downside was … That “Forest Defense is National Defense” slogan – along with that poster which the U.S. Forest Service had created to support their new forest fire prevention program didn’t exactly capture America’s attention.

I mean, it was the War Years after all. A lot was going in the country at that time. But long story short: the U.S. Forest Service’s first attempt at launching a successful forest fire prevention program sank without a trace.

So what do you do in a situation like this? You regroup. You try something different.

Disney & Bambi to the Rescue

And within the U.S. government, the thinking now was “Well, what if we got a celebrity to serve as the spokesman for our new forest fire prevention program? Maybe that would then grab the public’s attention.”

The only problem was … Well, again, these are the War Years. And a lot of that era’s A-listers (people like Jimmy Stewart, Clark Gable, even Mel Brooks) had already enlisted. So there weren’t really a lot of big-name celebrities to choose from.

But then some enterprising official at the U.S. Forest Service came up with an interesting idea. He supposedly said “Hey, have you seen that new Disney movie? You know, the one with the deer? That movie has a forest fire in it. Maybe we should go talk with Walt Disney? Maybe he has some ideas about how we can better capture the public’s attention when it comes to our new forest fire prevention program?”

And it turns Walt did have an idea. Which was to use this government initiative as a way to cross-promote Disney Studio’s latest full-length animated feature, “Bambi.” Which been first released to theaters in August of 1942.

So Walt had artists at Disney Studio work up a poster that featured the grown-up versions of Bambi the Deer, Thumper the Rabbit & Flower the Skunk. As this trio stood in some tall grasses, they looked imploring out at whoever was standing in front of this poster. Above them was a piece of text that read “Please Mister, Don’t Be Careless.” And below these three cartoon characters was an additional line that read “Prevent Forest Fires. Greater Danger Than Ever!”

According to folks I’ve spoken with at Disney’s Corporate Archives, this “Bambi” -based promotional campaign for the U.S. Forest Service’s forest fire prevention campaign was a huge success. So much so that – as 1943 drew to a close – this division of the Department of Agriculture reportedly reached out to Walt to see if he’d be willing to let the U.S. Forest Service continue to use these cartoon characters to help raise the public’s awareness of fire safety.

Walt – for reasons known only to Mr. Disney – declined. Some have suggested that — because “Bambi” had actually lost money during its initial theatrical release in North America – that Walt was now looking to put that project behind him. And if there were posters plastered all over the place that then used the “Bambi” characters that then promoted the U.S.’s forest fire prevention efforts … Well, it would then be far harder for Mr. Disney to put this particular animated feature in the rear view mirror.

Introducing Smokey Bear

Long story short: Walt said “No” when it came to reusing the “Bambi” characters to promote the U.S. Forest Service’s forest fire prevention program. But given how successful the previous cartoon-based promotional campaign had been … Well, some enterprising employee at the Department of Agriculture reportedly said “Why don’t we come up with a cartoon character of our own?”

So – for the Summer of 1944 – the U.S. Forest Service (with the help of the Ad Council and the National Association of State Foresters) came up with a character to help promote the prevention of forest fires. And his name is Smokey Bear.

Now a lot of thought had gone into Smokey’s creation. Right from the get-go, it was decided that he would be an American black bear (NOT a brown bear or a grizzly). To make this character seem approachable, Smokey was outfitted with a ranger’s hat. He also wore a pair of blue jeans & carried a bucket.

As for his debut poster, Smokey was depicted as pouring water over a still-smoldering campfire. And below this cartoon character was printed Smokey’s initial catchphrase. Which was “Care will prevent 9 out of 10 forest fires!”

Which makes me think that this slogan was written by the very advertising executive who wrote “Four out of five dentists recommend sugarless gum for their patients who chew gum.”

Anyway … By the Summer of 1947, Smokey got a brand-new slogan. The one that he uses even today. Which is “Only YOU can prevent forest fires.”

The Real Smokey Bear

Now where this gets interesting is – in the Summer of 1950 – there was a terrible forest fire up in the Capitan Mountains of New Mexico. And over the course of this blaze, a bear cub climbed high up into a tree to try & escape those flames.

Firefighters were finally able to rescue that cub. But he was so badly injured in that fire that he was shipped off to the National Zoo in Washington, D.C. and nursed back to health. And since this bear really couldn’t be released back in the wild at this point, he was then put on exhibit.

And what does this bear’s keepers decide to call him? You guessed it: Smokey.

And due to all the news coverage that this orphaned bear got, he eventually became the living symbol of the U.S. Forest Service’s forest fire prevention program. Which then meant that this particular Smokey Bear got hit with a ton of fan mail. So much so that the National Zoo in Washington D.C. wound up with its own Zip Code.

“Smokey the Bear” Hit Song

And on the heels of a really-for-real Smokey Bear taking up residence in our nation’s capital, Steve Nelson & Jack Rollins decide to write a song that shined a spotlight on this fire-fightin’ bruin. Here’s the opening stanza:

With a ranger’s hat and shovel and a pair of dungarees,

You will find him in the forest always sniffin’ at the breeze,

People stop and pay attention when he tells them to beware

Because everybody knows that he’s the fire-preventin’ bear

Believe or not, even with lyrics like these, “Smokey the Bear” briefly topped the Country charts in the Summer of 1950. Thanks to a version of this song that was recorded by Gene Autry, the Singing Cowboy.

By the way, it was this song that started all of the confusion in regards to Smokey Bear’s now. You see, Nelson & Rollins – because they need the lyrics of their song to scan properly – opted to call this fire-fightin’-bruin Smokey THE Bear. Rather than Smokey Bear. Which has been this cartoon character’s official name since the U.S. Forest Service first introduced him back in 1944.

“The Ballad of Smokey the Bear”

Further complicating this issue was “The Ballad of Smokey the Bear,” which was a stop-motion animated special that debuted on NBC in late November of 1966. Produced by Rankin-Bass as a follow-up to their hugely popular “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” (which premiered on the Peacock Network in December of 1964) … This hour-long TV show also put a “THE” in the middle of Smokey Bear’s name because the folks at Rankin-Bass thought his name sounded better that way.

And speaking of animation … Disney’s “Bambi” made a brief return to the promotional campaign for the U.S. Forest Service’s forest fire prevention program in the late 1980s. This was because the Company’s home entertainment division had decided to release this full-length animated feature on VHS.

What’s kind of interesting, though, is the language used on the “Bambi” poster is a wee different than the language that’s used on Smokey’s poster. It reads “Protect Our Forest Friends. Only You Can Prevent Wildfires.” NOT “Forest Fires.”

Anyway, that’s how Disney’s “Bambi” led to the creation of Smokey Bear. Thanks for bearin’ with me as I clawed my way through this grizzly tale.

-

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment8 months ago

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment8 months agoDisney’s Forgotten Halloween Event: The Original Little Monsters on Main Street

-

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment9 months ago

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment9 months agoThe Story of Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party: From One Night to a Halloween Family Tradition

-

Film & Movies8 months ago

Film & Movies8 months agoHow “An American Tail” Led to Disney’s “Hocus Pocus”

-

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment6 months ago

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment6 months agoDisney and Macy’s 90-Year Thanksgiving Day Parade Partnership: From Mickey’s First Balloon to Minnie’s Big Debut

-

Television & Shows4 months ago

Television & Shows4 months agoHow the Creators of South Park Tricked A-List Celebrities to Roast Universal – “Your Studio & You”

-

History4 months ago

History4 months agoThe Super Bowl & Disney: The Untold Story Behind ‘I’m Going to Disneyland!’

-

Podcast2 months ago

Podcast2 months agoEpic Universal Podcast – Aztec Dancers, Mariachis, Tequila, and Ceremonial Sacrifices?! (Ep. 45)

-

Film & Movies1 week ago

Film & Movies1 week agoBefore He Was 626: The Surprisingly Dark Origins of Disney’s Stitch