Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment

Why Clint Eastwood was a last minute addition to Disney-MGM’s “Great Movie Ride”

Greetings from the woods of Northern Georgia.

Nancy and I are still down in this neck-of-the-woods. Her Dad’s funeral was on Monday, so we’re still in the process of dealing with a lot of family obligations. And given that my laptop went belly-up on Super Bowl Sunday … Well, filing new stories for this site has become even more challenging.

Which is why — until Nancy can get the chance to properly format the Samsung Notebook that we purchased yesterday — I thought that I might reach back into JHM’s archives and resurrect a Why For column from February of 2005 that (given that Clint Eastwood is back in the news, thanks to his somewhat controversial “It’s Halftime in America” commercial) is somewhat newsworthy. So here goes:

Copyright 2012 Chrysler Group LLC. All rights reserved

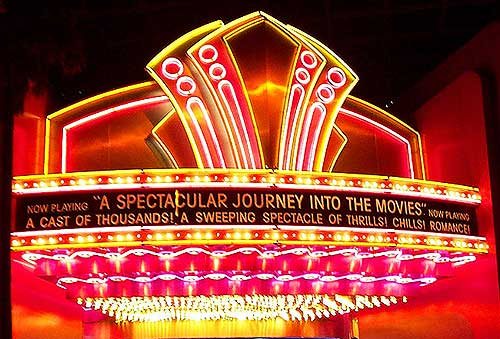

I really enjoyed Thursday’s story about how the Disney-MGM Studio theme park may be forced to change its

name this summer. I was wondering: Will the expiration of Disney’s

agreement with MGM/UA also result in “The Great Movie Ride” being

shut down too?

Rich G.

Copyright Disney Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved

Dear Rich G.

Actually, no. Don’t worry about it. The rights to use

the various movie scenes and characters that you see in “The Great Movie

Ride” were actually acquired under a separate series of agreements that

involved a number of different movie studios. Not just MGM/UA.

Take — for example — the “Alien” sequence in TGMR.

Disney got the rights to use those characters and that oh-so-spooky

setting by cutting a deal with 20th Century Fox, the studio that

actually produced this Ridley Scott film back in 1979. The “Raiders of the Lost Ark” Well of Souls scene? The Imagineers actually had to

approach two different companies — Paramount Pictures and Lucasfilm

Ltd.— in order to get permission to make AA versions of Indy &

Sallah.

Copyright Disney Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved

That process sounds kind of involved, don’t you think? Wait. It gets worse.

In addition to getting permission from the individual

studios in order to recreate a character and/or a setting from a

particular motion picture, WDI often times had to also persuade the

surviving members of a performer’s family to sign off on the likeness

of that AA figure as well. Otherwise Disney’s lawyers wouldn’t allow the

Imagineers to install the robotic version of that star in “The Great

Movie Ride.”

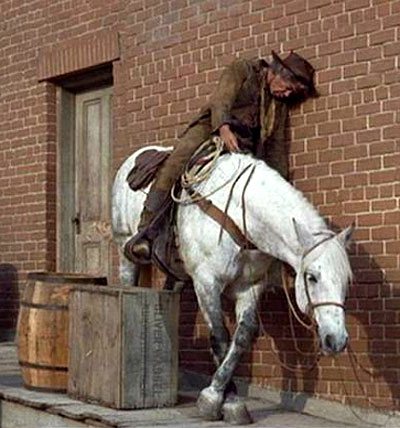

This is what actually happened with the Lee Marvin Audio

Animatronic that was supposed to be installed in the Western sequence

of that Disney-MGM ride. Directly across from the John Wayne figure.

Copyright 1965 Columbia Pictures. All rights reserved

“Wait a minute, Jim,” you sputter. “You’re telling me

that there was supposed to be a Lee Marvin AA figure in the ‘Great Movie

Ride’? How did that deal fall through? What exactly happened here?”

Well, to put it bluntly, Lee Marvin’s kids refused to sign WDI’s release

form. They were deeply offended that — out of all the roles their Dad

had played over the course of his 35-year-long career — Disney had

chosen to make a robotic version of Kid Shelleen (AKA The drunken

gunslinger that Marvin had played in the 1965 comic western, “Cat Ballou“).

Now it didn’t seem to matter to Marvin’s children that

their father had actually won an Academy Award for playing Kid

Shelleen. Or that many people had thought that Lee’s performance in “Cat

Ballou” was the very best thing that the late actor (Marvin died of a

heart attack in August of 1987) had ever done.

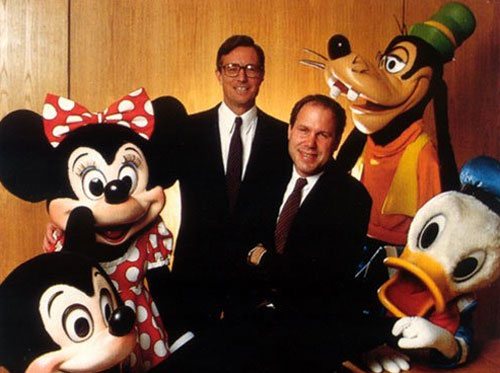

Mickey Mouse, Minnie Mouse, Frank Wells, Michael Eisner, Goofy and Donald

Duck. Copyright Disney Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved

All they knew was that everyone who ever rode

Disney-MGM’s “Great Movie Ride” was going to see — for years &

years yet to come — was a robotic version of their dad, drunk. This

was a concept that Lee Marvin’s kids just couldn’t live with. Which is

why they flat-out refused to sign WDI’s release form.

This — as you might understand — left the Imagineers

who actually were in charge of completing this attraction in a bit of a

lurch. These guys knew that they needed two well-known film legends in

order to properly fill out the performance space that had been built

into the Western section of “The Great Movie Ride.” And now that the Kid

Shalleen AA figure had to be pulled out of TGMR … Well, that left one

hell of a big hole.

Luckily, Frank Wells was able to come to WDI’s rescue.

He told the Imagineers: “Look, I’m personal friends with Clint Eastwood.

I was his attorney for a while. And — back when I was in charge of

Warners — I actually greenlit a number of Eastwood’s pictures. Which is

why I’m sure that he’d get a real kick out of seeing himself inside the

‘Great Movie Ride.’ So why don’t you work up an Audio Animatronic

version of him? And I’ll then get Clint to sign your release form.”

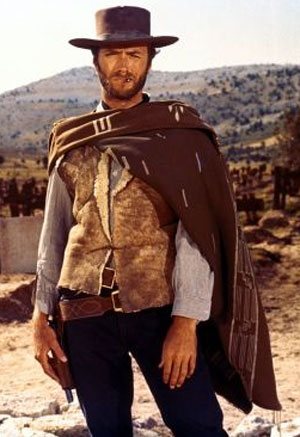

Copyright 1964 United Artists. All rights reserved

This WDI did almost immediately. They fabricated that AA

figure in record time. Of course, given the limited amount of time that

the Imagineers were working with here … Well, I guess you can

understand now why the GMR’s “Man with No Name” robot has such limited

movement.

Anyway … WDI quickly produces an Audio Animatronic

Clint Eastwood. The figure’s then sent east and quickly installed in

“The Great Movie Ride.” But — because Disney’s lawyers insisted that

the public wasn’t actually allowed to see this particular AA figure ’til

after Eastwood officially signs that release form … During the “Great

Movie Ride” ‘s entire test-and-adjust period, the “Man with No Name”

stood stoically in that doorway with a paper bag over his head.

Meanwhile, the Imagineers keep calling Frank Wells’

office, asking the Disney Company’s president: “Did you get Clint to

sign that release form yet.” But Wells is busy running the Mouse House.

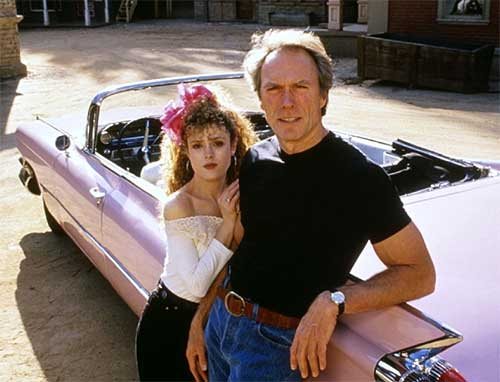

And Eastwood was working on “Pink Cadillac.” So neither of

these guys really has a hole in their schedule. And meanwhile the date

of Disney-MGM’s grand opening keeps getting closer and closer and closer

…

Bernadette Peters and Clint Eastwood in “Pink Cadillac.” Copyright 1989

Warner Bros. All rights reserved

Finally in April of 1989 (Less than 10 days before the

studio theme park was due to open to the public ), Wells persuades Clint

to get on a plane with him. So that the two of them can then fly on down

to Florida and go check out Disney’s newest theme park.

Mind you, Eastwood really isn’t a theme park kind of

guy. More importantly, he’s not all that crazy about planes. So it takes

an awful lot of weedling on Wells’ part to finally get Clint on

Mickey’s corporate jet. But eventually Eastwood does agree to go to

Orlando.

So Clint & Frank finally arrive at Disney-MGM and

begin touring the theme park. And this whole time, the Imagineers

assigned to the GMR are sweating bullets. They keep thinking about what

could to happen if Wells is wrong. What if Eastwood absolutely hates the “Man with No Name” AA figure? What will they do then?

Copyright Disney Enterprises, Inc.

All rights reserved

Finally, the two old friends get on board the “Great

Movie Ride.” They’ve got an entire theater car all to themselves. And —

as it quietly slides out of the attraction’s load area — a very

nervous lead picks up his walkie-talkie and says: “They’re on their way.

You can remove the paper bag now.”

And that’s literally what happens. Just seconds before

the theater car that’s carrying Clint and Frank rolls into the “Great

Movie Ride” ‘s Western section, an Imagineer sprints on stage and rips

the paper bag right off of the “Man with No Name” ‘s head. Then — bag

in hand — he slips back into the shadows, holds his breath and watches

what happens next.

The doors leading from the attraction’s gangland

shooting sequence now swings open. The theater car slides into the next

room. Eastwood spies the “Man with No Name” AA figure leaning against

that building. A big, very un-Dirty-Harry-like smile spreads across his

face. He turns to Wells and says: “Hey, that’s me!”

Right across from the Clint Eastwood AA figure is one of John

Wayne, recreating this Hollywood icon’s classic role in John

Ford’s “The Searchers.” Copyright Disney Enterprises, Inc.

All rights reserved

Frank turns to Clint and says: “You like?” Eastwood says: “Yeah. Sure.” Wells then whips out WDI’s release form and says: “Okay. Then sign this, please.”

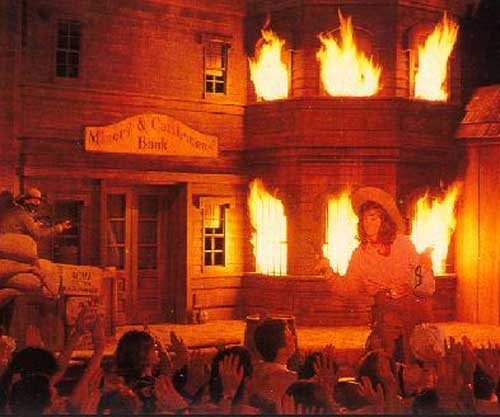

And literally — right in the middle of the action

portion of the GMR’s Western sequence (I.E. After the robber has tossed

the dynamite into bank. Which is why all those flames are belching out

of the windows) — Clint initials and then signs that release form.

Thinking that his old pal, Frank, had gone to such elaborate lengths to

try & amuse and surprise him.

To my knowledge, Eastwood has never learned about all

the problems that the Imagineers were having with Lee Marvin’s kids. Or

that his “Man with No Name” AA figure was really just a last minute

substitute for the Kid Shalleen Audio Animatronic that the Imagineers

had originally planned on installing in this attraction.

Copyright Disney Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved

Which is why I’m kind of hoping that this story never

gets back to Clint. I’d hate to think that — by posting this tale on

JHM (Which was told to me by the very same Imagineer who reportedly

raced on stage and ripped that paper bag off of the robotic Eastwood’s

head) — that this will somehow undermine what must be a pretty fond

memory of the late Frank Wells.

History

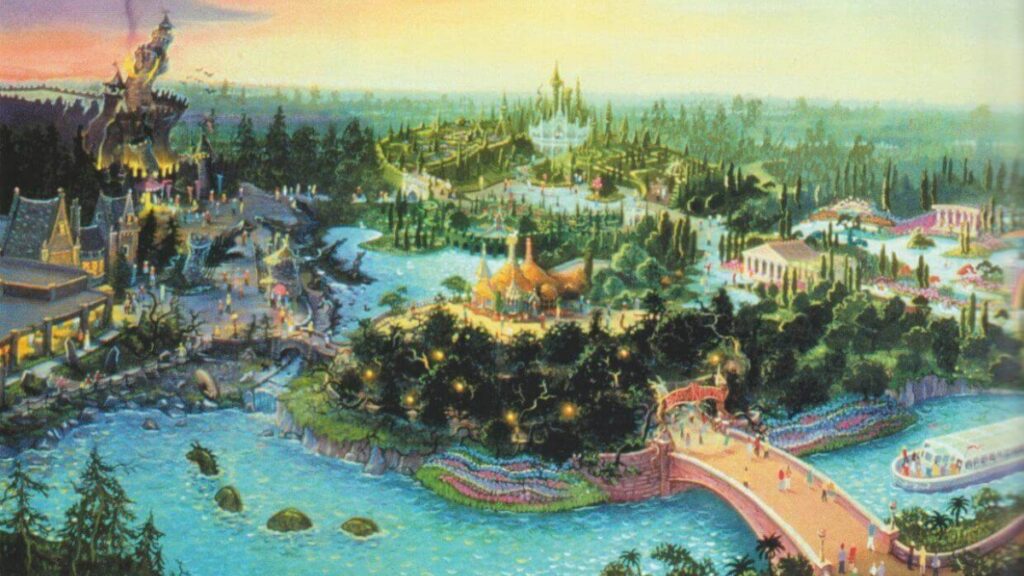

Why Disney’s Animal Kingdom’s Beastly Kingdom Was Never Built

This article is an adaptation of an original Jim Hill Media Three Part Series “Is DAK’s Beastly Kingdom DOA? (December 2000).

You can park your car in the “Unicorn” parking lot.

You can buy your admission ticket at a ticket booth with a huge dragon’s head on it.

And — for a while there — you could even catch a glimpse of a fire-breathing monster as you took a cruise along Discovery River.

So how how come it’s more likely that we will see real unicorns or dragons before the we ever see a “Beastly Kingdom”?

What happened? Why did Walt Disney World decide to scrub its years-in-the-making plans for expansion of its animal theme park? Why table what would seem to be a sure-fire addition to Disney’s Florida resort?

The Price Tag on Building a New Land

Those who have been following the Walt Disney Company’s over the years will not be be surprised to learn that the projected high price tag for building “Beastly Kingdom” factored heavily in upper management’s recent decision to postpone indefinitely any major expansion of Disney’s Animal Kingdom. After all, if times are so tough for the Mouse that they have to lay off the Magic Kingdom’s marching band as well as Epcot’s fife-and-drum corp, what are the chances the company would be willing to spend $200 to $300 million to add a new land to DAK? Slim to none.

Mind you, Mickey was perfectly willing to pony up the $100 million necessary to build the Animal Kingdom Lodge . But that’s different. That’s a hotel. That 1307 room resort starts making money for the Walt Disney Company the moment it opens.

But “Beastly Kingdom?” Exit surveys suggested that — even if Disney went forward with the construction of Beastly Kingdom, Walt Disney World wouldn’t see a large enough increase in attendance at WDW’s fourth theme park to justify the cost of actually building “Beastly Kingdom.”

Guests Wanted to See Unicorns and Dragons at Disney’s Animal Kingdom

The real irony here is that one of the only reasons Disney’s Animal Kingdom ever got built was that way back in 1993, guests who were surveyed about ideas for a fourth WDW theme park responded strongly to the notion of having a place in Florida where they could see unicorns and dragons.

Want to hear what folks were told about “Beastly Kingdom” back then? What follows is an excerpt from an exact transcript of an early marketing presentation on Disney’s Animal Kingdom. It describes in great detail the fun that would have been had in this part of the proposed park:

Beastly Kingdom Marketing Presentation (1993)

Beastly Kingdom is the realm of make believe animals, animals that don’t really exist, out of legends, out of fairy tales, out of storybooks. Like our legends and fair tales about imaginary animals, this land is divided into realms of good and realms of evil.

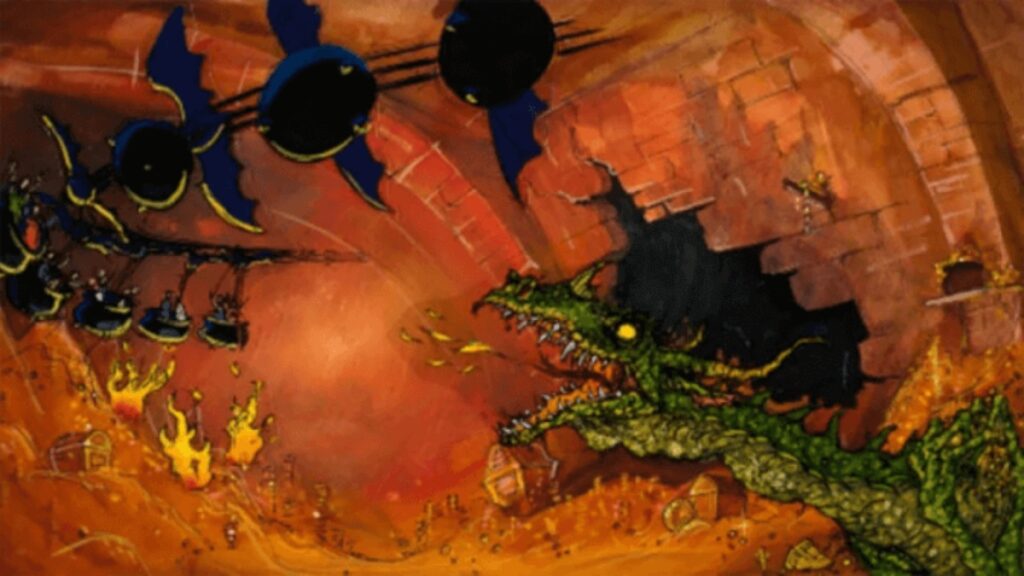

The evil side is dominated by DRAGON’S TOWER, a burned, wrecked castle inhabited by a greedy, fire breathing dragon. He hordes a fabulous treasure in his tower chamber. The castle is also inhabited by bats who speak to us from their upside down perches. The bats have a plan. They enlist our help trying to rob the dragon and fly us off on a wild chase. At last, we meet the fire-breathing dragon himself and barely escape un-barbecued.

The good side of this land is ruled by QUEST OF THE UNICORN. An adventure which sends us through a maze of medieval mythological creatures to seek the hidden grotto where the unicorn lives. There is also FANTASIA GARDENS. A gentle musical boat ride through the animals from Disney’s animated classic, “Fantasia.” Both the crocodiles and hippos from ” Dance of the Hours” and the Pegasus, fauns and centaurs from Beethoven’s “Pastoral” are found here.

Sounds pretty impressive, yes? Those WDW guests surveyed back in 1993 thought so. They identified “Beastly Kingdom” — with its mix of roller coasters and imaginary animals — as the number one reason that they’d want to visit this proposed fourth theme park.

Opening Disney’s Animal Kingdom is Real Animals

So why wasn’t “Beastly Kingdom” part of Disney’s Animal Kingdom when the park opened on April 22, 1998?

Again, cost played a big part in delaying construction of this highly anticipated land.

But DAK’s future planning had to be factored in too.

After all, it took the Walt Disney Company three years and $800 million just to get “Phase One” of DAK open. And — since the park’s name actually had the word “animal” in it — the Imagineers felt that opening day guests would want to see some actual live animals. So the majority of DAK’s capitalization was poured into building the Africa and Asian safari areas.

After that … well, someone had to make a decision. Disney’s Animal Kingdom was supposed to celebrate all animals: the live ones, the extinct ones, as well as the imaginary. The African and Asian enclosures would take care of the live animals.

But — in doing that — Disney blew through most of DAK’s initial budget. There was only enough money left to build one more land.

Which should the Mouse go for? Dragons or dinosaurs?

“Dinosaur”, Frustrated Imagineers, and Roller Coasters

In the end, the deciding factor here was the money the Disney Company had already blown on the soon-to-be-released computer animated film, “Dinosaur.” Even back in 1995, the Mouse had already invested upwards of $30 million into production of this movie. (Current estimates suggest that Disney may have spent as much as $150 million to finish this film, making “Dinosaur” even more expensive than James Cameron’s infamously over-budget 1997 epic, “Titanic.” ) Eisner wanted to make sure that Disney’s “Dinosaur” movie made a return on that investment, so he insisted that DAK feature an attraction that heavily hyped the forthcoming film.

That decision angered Joe Rohde and the other Imagineers on the Disney’s Animal Kingdom project. After all, one of the real reasons that DAK was being built was to keep WDW guests from leaving property to go visit Busch Gardens – Tampa Bay.

And what was Anheuser Busch’s Florida theme park best known for? Its animal displays and its killer roller coasters. With African and Asia, Disney had all the animals it needed. But where were the coasters?

“Dragon’s Tower” at Beastly Kingdom

According to Disney’s Animal Kingdom’s original plans, “Dragon’s Tower” was to have been this park’s signature attraction. That’s why the dragon was featured dead center in DAK’s logo. After guests visited WDW’s fourth theme park, this was going to be the ride they raved about the folks back home about.

What was so special about “Dragon’s Tower?” This high tech thrill ride would have been the Walt Disney Company’s first in-park use of an inverted roller coaster. This attraction would have also featured the largest AA figure ever built for a Disney theme park. The angry jewel encrusted dragon found in the ride’s finale — belching fire and smoke at your car as you zoomed on by — would have easily dwarfed any of the dinos found in “Countdown to Extinction” (AKA the “Dinosaur” ride).

But Eisner insisted that it was more important that DAK feature an area that synergized with the upcoming “Dinosaur” film.

“Beastly Kingdom” would have to wait ’til DAK’s “Phase Two” … which, back then, was to have been completed no later than Spring 2003.

Phase One – “Beastly Kingdom” Easter Eggs

So — with this understanding that “Beastly Kingdom” hadn’t been cancelled, but merely postponed — WDI agreed to scale back their initial plans for Disney’s Animal Kingdom. But, even as they mapped out plans for the “Phase One” version of DAK, the Imagineers deliberately put in some pretty broad hints of the fun yet to come when “Beastly Kingdom” finally opened. That’s why you can park your car in the “Unicorn” lot as well as buy your tickets at the dragon headed ticket booth.

Dragon on Discovery River

As for that fire-breathing dragon found in the cave down along Discovery River … before cost over-runs in other areas of DAK severely cut in the proposed budget for this part of the park, that make-believe monster was just one of many fantastical show elements that would have been found along this part of the river. That whole stretch of Discovery River was supposed to be one big coming attraction for “Beastly Kingdom.”

Had the Imagineers gotten all the money they were originally supposed to get, here’s what you would have experienced after your boat pulled away from the dock and began its cruise around Discovery River:

As you passed under the main bridge leading into Safari Village, you would have seen that the water ahead was littered with the shattered lances and crumpled armor of a great many fallen knights. But what horrible fate could have befallen all of these brave adventurers? A roar from the nearby cave offers a clue.

As your boat floated past the opening of the cave, you would have seen a duplicate of the dragon found in the cavern under Le Chateau de la Belle au Bois Dormant at Disneyland – Paris. Only WDW’s version would have been a lot more active than France’s sleepy monster. This dragon would have craned his neck out of the cave, roared at the guests and then breathed fire their way, before once again settling back down to sleep.

At this point, your boat driver would have started to get nervous. He would explain that he was worried that the dragon’s roaring would awaken the Kracken, a mythical Greek sea monster that was known to lurk along this stretch of Discovery River. Sure enough, the water around the boat begins to bubble ominously.

Off to one side, the huge fin of the Kracken suddenly cuts through the water. As the boat begins rocking back and forth, you’re certain you’re headed for a watery grave. Just then, your captain pulls out a lyre and begins plucking an odd tune. As the boat stops rocking and the water stops bubbling, the captain explains that music puts the Kracken back to sleep. Once that it’s safe to move on, the boat continues to head up river.

Just as you round the bend, your captain points off excitedly to your left. There on the shore, you catch a glimpse of a unicorn. The beautiful white creature — shrouded in mist as it stands in a picturesque grove of trees — paws the earth lightly with one hoof and nods its golden horn our way. The unicorn’s only visible for just an instant, but it truly is a beautiful sight.

As your boat pulls up to the dock in Harambe, you and your fellow guests would still be buzzing about the wonders you would have glimpsed on this leg of your adventure of Disney’s Animal Kingdom …

But of course … this didn’t happen. As DAK’s opening day grew nearer and it became obvious that the whole project was going over budget, great show elements like the Kracken and the Unicorn got cut from the “Phase One” version of the park. In the end, there was only enough money left in the budget for put one creature along the entire length of Discovery River.

Again — because Eisner insisted that “Dinosaur” be heavily synergized at DAK — the Imagineers decided to build a full-scale version of Aladar, the heroic iguanadon from the forthcoming film. That’s the AA dinosaur guests glimpsed roaring and splashing at water’s edge as their Discovery River boat floated past Dinoland USA.

Unfortunately, this decision left the other leg of the Discovery River boat cruise a five minute cruise past nothing. So Joe Rohde begged, pleaded and wheedled … and eventually got Eisner to kick in another couple of thousand dollars. With this tiny chunk of change, Joe was able to get the rock dragon that spews water along this part of the river built, as well as a very stripped down version of the park’s fire breathing dragon.

But don’t go looking for an Americanized version of Disneyland – Paris’s majestic AA dragon to be found along this part of Discovery River. Rohde’s Imagineers did the best they could with zero cash. All you’ll find here now is a somewhat dinky cave at water’s edge. As the boats went by, a ferocious roar would echo out of the cave, followed by a burst of flaming propane. These effects hinted that there was a dragon somewhere deep back inside that cave … but guests never really got a glimpse of the thing.

Discovery River Disappointments

As you might imagine, WDW visitors were pretty unimpressed with what they saw along Discovery River once DAK opened. In fact, this was the ride that guests singled out — right from Opening Day — as the worst attraction in all of Disney’s Animal Kingdom. After waiting in line for over an hour to board the boats, they were furious to find that there was virtually nothing to see along the water during their five minute journey to Harambe.

The Imagineers were obviously embarrassed by this situation. It was particularly frustrating to WDI because they knew that they had a solution to the Discovery River problem, ready to go. But Disney management was too cheap to put up the money to make the fixes.

But that had been typical of Disney management’s handling of the whole DAK project. Given the choice between doing things the right way and the inexpensive way, the Mouse always opted to go cheap.

Disney’s Animal Kingdom Opening Day Capacity Problems – “Camp Minnie-Mickey”

Take — for instance — how the Mouse handled the park’s capacity problems. When it became obvious that Asia was not going to ready in time for Disney’s Animal Kingdom’s April 1998 opening, the Imagineers began warning Disney management that DAK would not have a full day’s worth of shows and attractions. After having paid full price for admission, guests were sure to complain if they only got a half day’s worth of entertainment.

Eisner’s solution? Slap in a temporary land, similar to the “Mickey’s Birthdayland” area that the company had created for WDW’s Magic Kingdom way back in April 1988. From its first conceptual drawing right through to the first guest walking into Mickey’s house, “Mickey’s Birthdayland” had only taken 90 days to install.

Rohde and his Imagineers was appalled at Eisner’s suggestion. But — rather than tell the boss that his idea was terrible and that they wanted nothing to do with it — the DAK design team insisted that they were far too busy supervising construction in the rest of the park to work up any new temporary lands.

So Eisner ordered WDW’s entertainment office to take over the project. Using “Mickey’s Birthdayland” as their template, the entertainment staff came up with the concept for “Camp Minnie-Mickey.” Since there was no money available for even the cheapest of off-the-shelf rides, the WDW team opted to build “Camp Minnie-Mickey” around two low budget stage shows and several no budget character encounter areas.

How quickly and cheaply was “Camp Minnie-Mickey” thrown together? Do the float units the characters perform on in “Festival of the Lion King ” look familiar? They should. They’re the exact same parade floats that Disneyland ran up and down Main Street USA during the three year run of its “Lion King Celebration” parade.

Hope for Joe Rohde and Imagineers in Phase Two

Having this rapidly slapped together area sitting alongside lands that they’d spent years designing really irked the Imagineers. But Rohde advised his team to be patient and hold their tongues. After all, once Disney’s Animal Kingdom opened on April 22, 1998 and proved to be a huge success, then WDI would finally get the time and the money necessary to fix all the stuff that was wrong with the park.

Then the Imagineers could get the chance to put back all the stuff that was cut out of Discovery River. Then they could quietly pull the plug on that monstrosity, “Camp Minnie-Mickey.” Then WDI could finally get around to DAK’s “Phase Two” and build Beastly Kingdom.

Well, April 22, 1998 arrived and Disney’s Animal Kingdom opened …

But — after that — things didn’t quite go according to plan.

Eisner’s Expectations for Disney’s Animal Kingdom

Okay, kids — before we get back to the story of how “Beastly Kingdom” ended up on Disney Animal Kingdom’s (DAK) endangered species list — you need to understand what the Mouse’s original expectations were for its fourth Walt Disney World (WDW) theme park.

Here’s what Disney CEO Michael Eisner had hoped would happen when DAK opened on April 1998:

- Attendance levels would go through the roof at the Magic Kingdom, Epcot, and the Disney-MGM Studios, as a record number of visitors rushed down to Florida to check out WDW’s fourth theme park.

- Guests who had previously stayed on property at Walt Disney World hotels for four days would now book five day vacation packages — just to be sure that they didn’t miss any of the new shows and attractions that had recently been added to the resort.

- All this extra guest traffic would result in increased revenues for WDW’s hotels, shops and restaurants — which would have an immediate positive impact on the Walt Disney Company’s bottom line.

- Eisner and his staff would bask in the glow of the unparalleled success of Disney’s Animal Kingdom for a moment … then get right back to work, brain-storming ideas for WDW’s fifth theme park.

That’s what Uncle Michael had hoped would happen, anyway.

Reality proved to be infinitely harsher.

Walt Disney World Attendance in 1998

In spite of the Mouse’s rosy projections, Disney’s Animal Kingdom — in its first year of operation:

Actually drove down attendance levels at the other three WDW theme parks in 1998.

- 8% fewer guests visited the Magic Kingdom

- 9% fewer went to the Disney-MGM Studios

- Epcot’s attendance levels dipped a startling 11%

What happened? In a word — cannibalism.

How Does Opening a New Theme Park Affect the Other Theme Parks?

“Cannibalism” is the term Disney Company executives use to describe what happens when a brand new theme park opens and begins eating into the attendance levels of the older, more established parks at the same resort.

Epcot Opening

In 1982, when Epcot opened, that park initially cut significantly into the number of guests that annually visited the Magic Kingdom. However — over time — attendance levels at Magic Kingdom bounced back to what they once were after the newness of Epcot had worn off. Meanwhile, Epcot Center began drawing guests all on its own to WDW. In the end, it all worked out just fine.

Disney-MGM Studio Opening

A similar thing happened in May 1989, when the Disney-MGM Studio theme park threw open its gates. For almost a year, attendance levels at the Magic Kingdom and Epcot slumped while guests opted to go to the new WDW theme park rather than visiting their old favorites. But — once again, over time — the situation sorted itself out. Attendance levels at the older WDW parks slowly rose back up to where they once were, as the Disney-MGM Studios began luring millions of new tourists to come see Disney’s Florida resort.

Disney’s Animal Kingdom Opening

The Mouse had been anticipating that — when Disney’s Animal Kingdom opened — that it too would initially bleed guests away from the Magic Kingdom, Epcot, and the Disney-MGM Studios. That’s why Eisner had had the Imagineers add new attractions and/or complete major rehabs to each of the older WDW parks in the 18 months prior to DAK’s opening.

This was Uncle Michael’s brilliant scheme. He honestly believed that — if the Magic Kingdom, Epcot, and the Disney-MGM Studios each had new rides and shows for visitors to see — guests who had come down to WDW just to see Disney’s Animal Kingdom during its first year of operation would still end up of staying on property an extra day or so just to check out all the new stuff at the other parks.

On paper, that really did seem like a brilliant plan. Too bad reality got in the way.

Eisner’s Attendance Plan Doesn’t Go as Planned

What happened to ruin Eisner’s plan? For starters, Epcot’s heavily hyped new thrill ride — GM Test Track — was beset with horrible technical problems and ended up opening a full 18 months behind schedule. So that park really had nothing new to offer to returning WDW guests the year DAK opened.

Over at the Disney-MGM Studios, a much anticipated addition to the park — “David Copperfield’s Magic Underground” restaurant — never made it off the drawing board because the magician’s outside financing for the project disappeared. It would now be months after DAK’s opening before the studio theme park’s next big attraction — an East Coast version of Disneyland’s “Fantasmic” — would be ready to start entertaining WDW visitors.

As for the Magic Kingdom … truth be told, very little thought was put into to adding new shows and attractions to WDW’s first theme park. The Magic Kingdom had always been the favorite with Disney World visitors. Eisner and WDI felt that — what with the recent “Mickey’s Toontown Faire” redo as well as the 25th anniversary parade that was still running daily at the park — there was still plenty of semi-new stuff to entice people into making a return trip to the Magic Kingdom.

So — given all the money the Walt Disney Company had pumped into the Magic Kingdom, Epcot, and the Disney-MGM Studios to counter-act the effects of DAK’s opening — Eisner had anticipated that the attendance levels at WDW’s older parks would only dip by 5% in 1998. He was said to be furious when — almost across the board — attendance fell by almost twice that amount at all three of the other WDW theme parks.

This news immediately put WDW’s management team into crisis mode. The big boys in Burbank wanted attendance levels at each of the older WDW parks driven back up immediately. The managers of the Magic Kingdom, Epcot, and the Disney-MGM Studios reminded Eisner and Company that — in order to do that — they’d need money fast for new shows, parades and attractions. Eisner immediately agreed to free up some funds for the Florida park.

And where did Eisner get the money to create these new WDW shows? You guessed it. He snagged the funds that had been previously earmarked for expansion of Disney’s Animal Kingdom. Specifically, the money that would have been set aside for construction of “Beastly Kingdom.”

“Beastly Kingdom” Defunded – Problems at Animal Kingdom

Rohde and his Imagineers began complaining about the short-sightedness of Disney management’s fiscal planning. With that money gone, it would now be five years or more before there’d be any money in the budget to create any new significant attractions for DAK.

WDW managers admitted that this was true. But — given all the problems that Disney’s Animal Kingdom was having during its initial year of operation — it didn’t seem too wise right now to complain about the park’s future. Unless these problems got resolved quickly, it didn’t look like DAK would have much of a future.

What sort of problems was Disney’s Animal Kingdom having back then? You name it, the park was having problems with it.

Guests Getting Lost at Disney’s Animal Kingdom

Due to the twisty, turny nature of the park’s walkways as well as all the lush vegetation, guests were constantly getting lost as they walked through the park. Disney had to spend thousands on new, bigger signage for the theme park to help guests find their way around the place.

Guests Leaving Disney’s Animal Kingdom Early – Busy in the AM

Then there was all the troubles with DAK’s shops and restaurants. Particularly during the first eight months Disney’s Animal Kingdom was open (when only the African safari adventure was up and running), the Mouse had an awful time getting guests to stay inside the theme park past 4 p.m.

What was the problem? Due to the horrible heat in Florida, most of the animals along the African safari route would go lie down in the shade — disappearing entirely from view — by about 10 a.m. each morning. Once DAK management learned that its African menagerie had begun dropping from sight most days before noon, it quickly put the word out to WDW’s hotels to encourage their guests to visit DAK as early in the day as possible.

This resulted in a completely unworkable traffic flow situation at DAK. By 7:30 a.m. most mornings during that first summer of operation, the park would already be full. By 8 a.m., there’d be a two hour long line in the queue for the African safari ride as well as guests waiting for over an hour to get in to see “It’s Tough to Be a Bug.” Given that so few of Disney Animal Kingdom’s restaurants had been designed to serve breakfast, there were never enough places open at that hour to handle all those sleepy, cranky people looking for food. That first summer at DAK was a complete disaster.

But — as bad as the early morning hours at DAK were — the late afternoon was even worse. Why for? Because the crowds — having blown through Disney’s Animal Kingdom minimal number of shows and attractions in just a few hours — had already left the park for the day. By 4 p.m. most afternoons, you could have fired a cannon down the middle of the street in Safari Village and not have wounded a single soul.

Poor Merchandise and Restaurant Sales

Having the park virtually empty by late afternoon played hell with DAK’s projections for food and merchandise sales. All the managers of the park’s stores and restaurants were begging WDW management for help in turning around their depressed sales. (The folks running the giant “Rainforest Cafe” at the entrance of Disney’s Animal Kingdom were particularly desperate. They had paid big bucks for the right to build this branch of their restaurant chain right outside the entrance to WDW’s newest theme park. But most evenings, barely a third of the cavernous cafe had any guests in it.)

Fixing Disney’s Animal Kingdom with Night-Time Entertainment

WDW management tried to come up with a solution to DAK’s traffic flow problems. But it quickly became obvious that there’d be no quick fixes for this situation. After all, it wasn’t like Disney could do here what they did at Epcot and the Disney-MGM Studios to keep guests in the park at night. Since the lights in the skies and all the noise was sure to frighten the animals, a nightly fireworks display was out of the question.

There was also some talk of creating a special night-time parade to roll through the streets of Disney’s Animal Kingdom and entertain guests after dark. For a time, WDW management even considered bringing Disneyland’s much maligned “Light Magic” streetacular to Florida to provide after-hours entertainment at DAK.

But Rohde and his team of WDI designers quickly killed any talk about night-time streetaculars at Disney’s Animal Kingdom. They pointed out that the park’s streets and trails were just too tight and narrow to allow even the smallest floats easy passage. The Imagineers reminded WDW management how much trouble DAK’s small day-time parade — “The March of the Art-imals” — was having making its way around the park in broad daylight. Imagine how much trouble a similar parade would have making its way around DAK in the dark.

Fix Disney’s Animal Kingdom’s Problem with Attractions – Build “Beastly Kingdom”

Rohde’s team insisted that the solution to the traffic flow problems at Disney’s Animal Kingdom was obvious: beef up the parts of the park that didn’t rely on real animals. That meant adding new shows to Dinoland USA as well as finally building Beastly Kingdom. By adding these additional shows and attractions, WDW management would give guests a real reason to stay at DAK after dark — rather than trying to trick visitors into staying with a lame after-hours parade and/or a smallish fireworks display.

Privately, officials in WDW management agreed with the Imagineers that this was the logical, reasonable way to fix Disney’s Animal Kingdom. The trouble was that the folks back in Burbank weren’t acting reasonably or logically right now. Disney Company management had panicked when they had seen the drastic dip in attendance at WDW’s three other theme parks. Now they were running scared.

And Eisner had already okayed WDW management’s decision to grab the money that had been earmarked for DAK expansion and use it for bolstering sagging attendance at the other three WDW theme parks. That meant that Imagineering had next to no money left to fix all the glaring problems at Disney’s Animal Kingdom. More ominously, it now looked like it would be five years — or more — before WDI could afford to add any significant new attractions to DAK.

It was a very depressing time for the Disney’s Animal Kingdom design team. But — again — Rohde told his Imagineers not to lose heart. He told them that DAK — in particular “Beastly Kingdom” — might still be saved yet.

Competition for Disney – Universal Studios’ Islands of Adventure

For Joe knew that Seagrams / MCA was spending two billion dollars to expand its Universal Studios Florida theme park complex — which was just down the road from WDW. And the centerpiece to this ambitious expansion project was a brand new theme park: Universal Studios’ Islands of Adventure.

Rumors were flying around the theme park community that Seagrams / MCA was spending hundreds of millions of dollars on their new Florida park because they were out to top Disney. Universal wanted “Islands of Adventure” to have such amazing state-of-the-art attractions that this park would top any ride that could be found at Walt Disney World.

Secretly, Rohde and his Imagineers were hoping that Universal Studios’ Islands of Adventure would be a huge success. Why for? Because the Walt Disney Company would then be embarrassed that it didn’t have the best rides in Florida anymore. And then maybe the Mouse would get worried that they were starting to lose guests to the new Universal park.

If that happened … well, then Eisner would finally have to open up his wallet then, wouldn’t he? Just as a matter of pride, he’d have to insist that WDI install the greatest rides that they could come up with at each of the WDW parks. For Disney’s Animal Kingdom, that could only mean that the Imagineers would finally get the chance to build “Beastly Kingdom.”

That was how Joe Rohde hoped things would play out, anyway.

Buzz Around Islands of Adventure Opening

Well, in the spring of 1999, Universal Studios’ Islands of Adventure did finally open up. Unfortunately, it was not quite the roaring success Joe had hoped for.

Worse still, some of the attractions to be found in the new park looked awfully familiar …

December 1998. Everyone at Walt Disney Imagineering (WDI) is abuzz with news about Universal Studios expansion plans for its Florida property.

“I’ve heard that — on opening day — they’re going to have three mega-coasters up and running.”

“Well, I’ve heard that their ‘Spiderman’ attraction is going to blow the doors off ‘Star Tours’ and ‘Body Wars.'”

“That — plus ‘Jurassic Park – The Ride,’ that ‘Dudley Do-Right’ flume thing as well as the ‘Popeye’ raft ride. This new Universal park sound better than anything we’ve got in Florida.”

Were these Imagineers frightened at the thought of all these great attractions being built in a theme park just down the street from WDW?

Hell no. The folks at WDI were thrilled that Seagrams was spending a reported $2 billion to remake their Universal Studios Florida theme park into a Disney quality resort. Why? Because that meant that the Mouse would finally have some serious competition in Orlando.

You see, Disney CEO Michael Eisner is a very competitive guy. He hates to lose — at anything.

If attendance at WDW started to noticeably slip due to the Mouse losing customers to Universal’s new theme park, Michael would have to do something. Eisner’s enormous ego just wouldn’t be able to handle the idea of Disney being No. 2 in the Orlando market.

So he’d turn to the Imagineers and say: “Make the best attractions you can.”

Not “Make the best attraction you can on a limited budget.” (i.e.: WDI’s controversial rehab of Epcot’s “Journey into Imagination” ride. During its three months of operation, the revamped version of that Future World attraction racked up more guest complaints than most shows produce in a year.)

Not “Make the best attraction you can with minimal changes to the pre-existing ride building.” (i.e.: The Magic Kingdom’s “Buzz Lightyear’s Space Ranger Spin” actually runs its ride vehicles along the very same track and layout the building’s previous tenants — Delta’s “Dreamflight” and the unsponsored “Take Flight” — used.)

Not “Make the best attraction that reflects the sponsor’s agenda” (i.e.: Any exhibit you’ll find inside either version of “Innoventions.”)

Just “Make the best attractions you can.” Period.

And WDI would absolutely love to hear Michael Eisner say this.

The Imagineers Finally Able to Build Attractions

For years now, the Disney Imagineers been developing ideas for absolutely killer theme park attractions, only to be told by Disney Company senior management that ” Gee, we’d love to build that … but it’d be too expensive” or “No one else in the industry is doing that” or — worst of all — “We don’t have to try that hard.”

So now — for the first time ever — it appeared that Walt Disney World was going to have some real competition in Florida. And the top guys at the Mouse Works must have been taking Universal’s Islands of Adventure seriously, for — in January 1999 — they ordered WDI to work up a WDW contingency plan.

The purpose of the plan was this: Should Universal’s Islands of Adventure actually begin to seriously nibble away at Disney World attendance levels in 1999, the Mouse wanted a way to quickly recapture those wandering visitors. WDI felt that the easiest way to get folks excited about going back to WDW again was to add a huge new E ticket attraction for each of the four Florida parks. More importantly, they wanted to have each of these rides up and running in time for the kick-off of Walt Disney World’s 30th anniversary celebration in October 2001.

“Fire Mountain” at Magic Kingdom

The Magic Kingdom was to have gotten “Fire Mountain,” a state-of-the-art roller coaster themed around story elements from Walt Disney Pictures’ Summer 2001 animated release, “Atlantis.” What would have truly been intriguing about “Fire Mountain” is that it was to have been the world’s first morphing coaster. Visitors would start their ride seated securely in their ride vehicle. At the midway point in the attraction — as “Fire Mountain” erupted — the bottom would have dropped away from their ride vehicle, leaving the riders dangling from above as they zoomed through the rest of the ride.

“Villain Ride” at Disney-MGM Studios

Over at the Disney-MGM Studios, that park’s signature attraction — “The Great Movie Ride” — would have gotten a massive makeover. In its place, visitors would have been asked to put on 3D glasses before taking a trip through the Chinese Theater’s “Villain Ride.” Here, WDW visitors would have been menaced by three dimensional recreations of Disney’s most famous fiends before the forces of good finally came to their rescue.

“Mission: Space” at Epcot

Epcot would have had its dated Future World “Horizons” pavilion pulled down to make way for the new “Mission: Space” attraction. This cutting-edge ride would use centrifugal force to give visitors the sensation of being blasted out into space. They would also feel tremendous G-forces pressing them down into their seats as well as a brief moment of weightlessness before their ride vehicle made re-entry.

“Beastly Kingdom” at DAK

As for Disney’s Animal Kingdom … well, since it was the least developed of all four of the WDW theme parks, adding just one new attraction wouldn’t have given visitors enough incentive to return to DAK. So the Imagineers opted to go for broke here. They suggested adding a whole new land to Disney’s Animal Kingdom.

Which land? You guessed it, kids. “Beastly Kingdom.”

Disney’s Plan to Counter-Act Universal’s Island of Adventure

Disney Management reviewed WDI’s plan in March of 1999 and agreed to put it into action if … and this is a really big “if” here, folks … it could be proven that Universal Studios’ Islands of Adventure was having a significant detrimental effect of WDW’s attendance levels.

So — for the first time in the history of the Walt Disney Company — the Imagineers actually hoped and prayed for a competitor’s theme park to succeed. For — if Islands of Adventure really had an impact on WDW’s attendance — all of their great new proposed attractions would actually make it off the drawing board.

After two months of soft openings, Universal finally did officially open Islands of Adventure (IOA) on May 28, 1999. Just as the Imagineers had hoped, IOA had it all. Three huge roller coasters. Their state-of-the-art “Spiderman” attraction. Three water-based rides (“Jurassic Park – The Ride,” “Dudley Do-Right’s Ripsaw Falls,” and “Popeye’s Bilge Rat Barges”). Everything a modern theme park needs to succeed.

Well … almost everything.

What was missing?

Crowds.

Was Universal Studios’ Islands of Adventure a Flop?

To this day, no one knows quite what went wrong with the launch of Universal Studios’ Islands of Adventure. Some blame the marketing of the new park and resort, which somehow lead the public to believe that IOA wasn’t a whole new theme park, but rather just a new land that had been added to Universal Studios Florida (USF). (This certainly was a popular explanation within the boardroom at Seagrams. They asked for — and received — the resignations of most of USF’s marketing staff.)

Whatever the reason, the crowds just did not come out for IOA during its first year of operation. Universal’s new theme park under-performed in a spectacular manner, drawing less than half the projected number of bodies Seagrams had said would visit its revamped resort in 1999. Worse still, the limited number of visitors IOA got seems to have all been bodies that the new park lured away from its older Florida theme park. Unconfirmed reports suggest that attendance at Universal Studios Florida may have fallen off by as much as 30% during IOA’s first few months of operation.

But worst of all — at least from the Imagineers’ point of view — is that IOA was having virtually no impact on WDW’s theme parks. As the months went by, it became obvious that — in spite of the $2 billion Seagrams had spent — their revamped resort was having little or no effect on Disney World attendance levels.

Without proof that IOA was impacting WDW’s attendance levels, WDI’s ambitious plans for adding a brand new E-Ticket attraction to each of the Disney Company’s Florida theme parks by October 2001 seemed doomed to failure. Sure enough, Walt Disney Imagineering president Paul Pressler called a meeting at WDW’s WDI headquarters earlier this year to announce a radical rethink of the Florida property’s expansion plans.

Did Walt Disney World Respond to Islands of Adventure?

At this meeting, Pressler said that — since IOA had obviously proven to be a non-threat to WDW attendance levels — there was no reason to go forward with the previously announced aggressive building program. In its place, Paul proposed a significantly spread out schedule as to which Florida Disney theme park got new attractions and when.

Pressler believed that it was now time to prioritize. WDW attraction construction money would be allocated first to whichever Disney theme park in Florida most needed a boost in attendance. That was obviously Epcot, which perpetually had problems drawing visitors back in for return visits. That’s why the Walt Disney Company opted to stage its 15 month-long Millennium celebration inside this Florida park.

Under the new schedule, the first new WDW E-ticket would be built inside on Epcot. “Mission: Space” would still rocket visitors off into the cosmos. Only now these visitors would have to wait ’til 2003 before they got the chance to board Disney’s shuttle simulator.

Next up would be the Disney-MGM Studios’ E-Ticket. However, construction on the “Villain Ride” wouldn’t even begin ’til 2003. Pressler’s plan was to have the “Villain Ride” up and running by May 2004 — just in time for the studio theme park’s 15th anniversary celebration.

After that, “Fire Mountain” would rise up over at the Magic Kingdom in 2006. This volcano-based Adventureland attraction would serve as the centerpiece of WDW’s 35th anniversary celebration.

Then in 2008, Disney’s Animal Kingdom would finally get its new E-Ticket. Just in time for that park’s 10th anniversary, “Beastly Kingdom” would throw open its doors. Visitors would then get to sample the thrills of “Dragon’s Tower” and wander the leafy green maze over at “Quest for the Unicorn.”

Obviously, Imagineer Joe Rohde and his DAK design team were tremendously disappointed with this last bit of news. But Rohde — ever the optimist — tried to stress the positive in this tough situation. “Okay, so it’s going to open 10 years late,” Joe said. “But at least ‘Beastly Kingdom’ will finally be part of Disney’s Animal Kingdom.”

At least, that was the plan … until Eisner got around to visiting Universal Studio’s Islands of Adventure in January 2000.

Eisner Visits Universal Studios’ Islands of Adventure

Eisner and a small entourage quietly toured the park that day, riding most of the major attractions as well as scoping out a lot of the shops and restaurants. After Michael got back to California, he told the Imagineers that he thought that — while IOA wasn’t quite up to Disney standard — the place still looked pretty good.

There was a pause. Then Michael added “But a few of those attractions looked awfully familiar.”

This is where one of the scummier secrets of the theme park industry gets revealed: theme parks regularly steal attraction ideas from one another. Just like in the computer world or the auto industry, industrial espionage is just one of the many ways that theme park companies like Disney, Universal, Six Flags, and the Cedar Fair Corporation try to stay ahead of the competition.

Of course, Disney didn’t help matters by laying off hundreds of Imagineers following the disastrous opening of Euro Disney. Many of these disgruntled former Imagineers walked out the door, carrying with them the plans for the proposed attractions they had been working on when the Mouse let them go.

“Dragon’s Tower” at Islands of Adventure – Disney Imagineer Layoffs Create “Lost Continent”

Among these folks were several Imagineers who had been working on the “Dragon’s Tower” attraction for DAK’s “Beastly Kingdom.” After a few months, these former WDI employees got hired by Universal to work on their proposed second theme park for Florida. They ended up being assigned to work on that park’s “Lost Continent” area.

“You guys got any ideas for attractions for this part of the park?,” their Universal bosses asked.

Indeed they did.

“Borrowed” Ideas for Disney Attractions

Now, before you get all indignant about the idea of Universal stealing ride ideas from Disney, please keep in mind that the Mouse has also been doing it for years. For example: how do you suppose the Skyway and Monorail ended up in Disneyland? Walt saw similar attractions while touring amusement parks in Europe in the 1950s. He decided to “borrow” the concepts of these rides from those European venues for installation at his Anaheim park.

And — while Tony Baxter is universally recognized as a modern master of Imagineering, having come up with the concepts for such classic Disney theme park attractions as “Big Thunder Mountain Railway” and “Splash Mountain” — employees of Knotts Berry Farm are all too willing to point out the similarities between those attractions and Knotts’ “Calico Mine Train” and “Log Ride.” Given that Baxter has admitted to spending a lot of his free time back in the 1960s when he was a Disneyland employee prowling around Knotts, is it possible that Tony could have — just like his hero, Walt — “borrowed” the concepts for these Knotts attractions to use as the basis for “Big Thunder” and “Splash Mountain?”

Anything’s possible, kids.

“Dragon’s Tower” becomes “Dueling Dragons”

Anywho, back to Islands of Adventure … is “Dueling Dragons” an obvious rip-off of “Beastly Kingdom”‘s proposed “Dragon’s Tower” ride? Perhaps. But how can you rip off something that hasn’t actually been built yet?

Some might argue that Universal — being the first theme park company to build a mega-coaster that featured a dragon storyline with a queue area that was themed around a decrepit castle — must now get credit for creating that attraction. Which means Universal effectively owns that ride idea. That would mean that — should Disney ever go forward with their “Dragon’s Tower” attraction idea — the Mouse would now appear to be copying ride ideas from Universal, rather than the other way around.

Never mind that Disney came up with the original idea for a dragon-based coaster. Never mind that Universal may have acquired the concept for their dragon coaster attraction under somewhat questionable circumstances. In the end, all that matters is: Who built the ride first? Since Universal was the first to build a dragon-based coaster, that ride concept now belongs to them.

“Beastly Kingdom” Loses Its Icon – Land Cancelled

And — since Eisner didn’t want it to appear as if Disney was stealing ride ideas from Universal — he asked the Imagineers to remove the “Dragon’s Tower” ride from all future plans for “Beastly Kingdom.” But — without the tumble-down burned-out castle (that would have served as “Dragon’s Tower”‘s show building) to serve as the centerpiece for this proposed addition to WDW’s fourth theme park — “Beastly Kingdom” was left without a “weenie,” a strong visual element that would lure people down into this side of the park. Without “Dragon’s Tower,” “Beastly Kingdom” now seemed kind of pointless.

Dinoland USA Expansion

As painful as it might be, Joe Rohde and his Imagineering team now had to face facts. “Beastly Kingdom” — as they had originally planned it — was dead. WDI would now have to abandon all the witty plans they’d come up with for this part of the park and dream up some new attractions for DAK’s east side.

Mind you, there was no time to mourn “Beastly Kingdom”‘s demise. Rohde and his team were too busy fighting with Disney management over their bargain basement expansion plans for DAK’s Dinoland USA. Assuming that — when Disney’s “Dinosaur” movie opens in theaters later this month — this side of the park will see a huge surge of new traffic, Eisner ordered that several lightly themed off-the-shelf carnival-style rides be added to Dinoland USA to increase capacity.

Rohde was said to be furious when he learned of this plan, particularly since WDI had already put together an elegant expansion plan for DAK’s dino area. He’s reportedly particularly enraged that the name that his Imagineering team came up with for a runaway-mine-car-through-an-abandoned-dinosaur-dig ride — the Excavator — for Dinoland USA’s “Phase II” will now be used for a smallish kiddie coaster Eisner is quickly tossing into the area.

Adding to Rohde’s aggravation: DAK’s ‘temporary’ area — Camp Minnie-Mickey — was becoming all the more permanent as each day went by. Exit polls showed that this area’s “Festival of the Lion King” show was the most popular attraction in all of Animal Kingdom. So popular that Disney had to add additional seats to DAK’s “Lion King” theater to increase the show’s capacity. And — with “Lion King III,” another direct-to-video sequel to the original 1994 film, currently in the works — it could now be years before the “Lion King” phenomenon finally fades … leaving all the land around that once-thought-to-be-temporary theater available again for development.

As you can see, Rohde and his Imagineers didn’t have time to moan over “Beastly Kingdom”‘s loss. They’re too busy fighting with Disney Company management, trying to keep Eisner and Co. from ruining the park with their bone-headed cost-cutting maneuvers.

Editor’s Note: This article is an adaptation of the original three-part series from Jim Hill Media, “Is DAK’s Beastly Kingdom DOA?” (December 2000). Pandora – The World of Avatar officially opened at Disney’s Animal Kingdom on May 27, 2017, in the area originally proposed for Beastly Kingdom.

Will There Ever Be a “Beastly Kingdom” at Walt Disney World?

But is “Beastly Kingdom” really dead? At least for the immediate future, it would seem so. Any ambitious plans the Mouse may have had for expansion of Disney’s Animal Kingdom are now completely on hold.

Why for? Because there’s so much other stuff at DAK that’s currently in urgent need of repair. For example: Conservation Station is thought to be a complete disaster. Visitors repeatedly name that area as their least favorite part of Disney’s Animal Kingdom. So the Imagineers are frantically searching for ways to fix up that facility.

And then there’s Kali River Rapids. Though only a year old, the centerpiece attraction for DAK’s Asia area is already falling apart. There are currently so few of that attraction’s original rafts in working condition that visitors often have to wait as much as an hour in line before there’s a raft available for them to board.

But all those Disney unicorn and dragon lovers out there shouldn’t completely lose heart. Long-time Disney theme park observers know it’s wise never to consider a really great concept for a theme park show or attraction completely dead. For the Imagineers have this awful tendency to recycle abandoned ideas.

Consider Disneyland’s long proposed Discovery Bay. Though Tony Baxter hatched the concept for this Jules Verne-meets-Gold Rush-era-San-Francisco Frontierland expansion back in 1977, it wasn’t until 1992 that elements of this proposed Disneyland addition finally turned up in a Disney theme park. Unfortunately for all those US-based Discovery Bay fans, the park that got the land (DiscoveryLand, to be exact) that was inspired by Tony’s concept art was Disneyland – Paris. But some of Discovery Bay did finally make it off the drawing board.

So who knows? Maybe in ten years or so, some Imagineer may come with a clever way to rework the “Dragon’s Tower” storyline. Perhaps that long rumored South American Disney theme park will have a Sleeping Beauty’s castle with a thrill ride — rather than a walking tour — as its main attraction? Maybe this thrill ride will feature a huge AA version of the Maleficent dragon, snarling and breathing fire at riders as they whiz through the attraction’s finale? Stranger things have happened, kids.

Here’s hoping that — some day, in some way — dragons and unicorns turn up in a Disney theme park.

After all, there’s always room for a little more magic in the Magic Kingdom.

Want more behind-the-scenes Disney stories? Dive deeper into the magic with The Disney Dish podcast, where Jim Hill and Len Testa explore Disney news and park history. Listen now at The Disney Dish on Apple Podcasts. For exclusive bonus episodes and even more insider content, check out Disney Unpacked on Patreon.

Television & Shows

The Untold Story of Super Soap Weekend at Disney-MGM Studios: How Daytime TV Took Over the Parks

A long time ago in a galaxy that … Well, to be honest, wasn’t all that far away. This was down in Florida after all. But if you traveled to the WDW Resort, you could then experience “Star Wars Weekends.” Which ran seasonally at Disney’s Hollywood Studios Disney World from 1997 to 2015.

Mind you, what most folks don’t remember is the annual event that effectively plowed the road for “Star Wars Weekends.” Which was “Super Soap Weekend.” That seasonal offering — which allowed ABC soap fans to get up-close with their favorite performers from “All My Children,” “General Hospital,” “One Life to Live” and “Port Charles” — debuted at that same theme park the year previous (1996).

So how did this weekend-long celebration of daytime drama (which drew tens of thousands of people to Orlando every Fall for 15 years straight) come to be?

Michael Eisner’s Daytime TV Origins and a Theme Park Vision

Super Soap Weekend was the brainchild of then-Disney CEO Michael Eisner. His career in media began with short stints at NBC and CBS, but it truly took off in 1964 when he joined ABC as the assistant to Leonard Goldberg, who was the network’s national programming director at the time.

Eisner quickly advanced through the ranks. By 1971, he had become Vice President of Daytime Programming at ABC. That meant he was on the scene when One Life to Live joined the lineup in July 1968 and when All My Children made its debut in January 1970. Even after being promoted to Senior Vice President of Prime Time Programming in 1976, Eisner stayed close to the daytime division and often recruited standout soap talent for ABC’s primetime shows.

Fast forward nearly two decades to July 31, 1995. The Walt Disney Company announced that it would acquire ABC/Cap Cities in a $19 billion deal. Although the acquisition wasn’t finalized until February 1996, Eisner was already thinking ahead. He wanted to use the stars of All My Children, One Life to Live, and General Hospital to draw people to Disney’s theme parks.

He had seen how individual soap stars were drawing huge mall crowds across America since the late 1970s. Now he wanted to bring dozens of them together for something much bigger.

Super Soap Weekend Takes Over Disney-MGM Studios

The very first Super Soap Weekend was announced in June 1996, just a few months after the ABC deal closed. The event was scheduled for October 19 and 20 at Disney-MGM Studios and was a massive success.

The weekend featured panel discussions, autograph sessions, and photo opportunities with the stars of ABC’s daytime dramas. Thousands of fans packed the park for the chance to meet their favorite actors. Due to the overwhelming response, the event became an annual tradition and was eventually moved to Veterans Day weekend each November to better accommodate attendees.

Longtime fans like Nancy Stadler, her mom Mary, and their close friend Angela Ragno returned year after year, making the event a personal tradition and building lifelong memories.

West Coast Events and the ABC Soap Opera Bistro

Disney even tried to recreate the event out west. Two Super Soap Weekends were held at Disneyland Resort, one in April 2002 and another in June 2003.

At Disney’s California Adventure, Eisner also introduced the ABC Soap Opera Bistro, a themed dining experience that opened in February 2001. Guests could dine inside recreated sets from shows like General Hospital and All My Children, including Kelly’s Diner and the Chandler Mansion. The Bistro closed in November 2002, but for fans, it offered a rare opportunity to step into the world of their favorite soaps.

SOAPnet, Port Charles, and the Expansion of Daytime TV at Disney

Eisner’s enthusiasm for soaps extended beyond the parks. In January 2000, he launched SOAPnet, a cable channel dedicated to prime time replays of ABC’s daytime dramas.

During his time at Disney, General Hospital also received a spin-off series titled Port Charles, which aired from June 1997 to October 2003. The show leaned into supernatural plotlines and was another example of Eisner’s commitment to evolving and expanding the soap genre.

The Final Curtain for Super Soap Weekend

In September 2005, Eisner stepped down after 21 years as head of The Walt Disney Company. Bob Iger, who had previously served as President of ABC and Chief Operating Officer of ABC/Cap Cities, took over as CEO. While Iger had deep ABC credentials, he didn’t share Eisner’s passion for daytime television.

In the fall of 2008, Disney hosted the final Super Soap Weekend at what was then still called Disney-MGM Studios. That same year, the park was rebranded as Disney’s Hollywood Studios, and Disney began shifting away from television-focused experiences.

Within the next five years, the rest of Eisner’s soap legacy faded. One Life to Live was canceled in January 2012. SOAPnet was rebranded as Disney Junior in February 2013. Later that year, All My Children ended its 41-year run on ABC.

Only General Hospital remains on the network today, the last standing soap from the golden age of ABC Daytime.

A New Chapter for Daytime TV and Super Soap Fans

The soap genre may have faded from its former glory, but it’s not gone. On February 24, 2025, CBS premiered a brand-new daytime drama called Beyond the Gates, marking the first new soap launch in years.

Meanwhile, All My Children alum Kelly Ripa has been actively working on a revival. In September 2024, she mentioned a holiday-themed movie set in Pine Valley that would bring back many original cast members. The project was in development for Lifetime, though its current status is unclear.

And what about Super Soap? Fans like Nancy and Angela still hope Disney will bring it back. Even if it only featured the cast of General Hospital, it would be a welcome return for longtime viewers who miss that one weekend a year where the magic of Disney collided with the drama of daytime TV.

If you want to hear firsthand what it was like to be part of Super Soap Weekend, be sure to listen to our I Want That Too podcast interview with actor Colin Egglesfield. He shares behind-the-scenes memories from his days as Josh Madden on All My Children and what it meant to be part of one of the most unique fan events in Disney park history.

History

The Super Bowl & Disney: The Untold Story Behind ‘I’m Going to Disneyland!’

One of the highlights of the Super Bowl isn’t just the game itself—it’s the moment when the winning quarterback turns to the camera and exclaims, “I’m going to Disney World!” This now-iconic phrase has been a staple of post-game celebrations for decades. But where did this tradition begin? Surprisingly, it didn’t originate in a stadium but at a dinner table in 1987, in a conversation involving Michael Eisner, George Lucas, and aviation pioneers Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager.

The Unlikely Beginning of a Marketing Sensation

To understand the origins of this campaign, we have to go back to December 1986, when the Rutan Voyager became the first aircraft to fly around the world without stopping or refueling. Pilots Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager completed the nine-day journey on December 23, 1986, flying over 26,000 miles before landing at Edwards Air Force Base. Their historic achievement earned them national recognition, and just days later, President Ronald Reagan awarded them the Presidential Citizen Medal at the White House.

Meanwhile, Disney was gearing up for the grand opening of Star Tours at Disneyland, set for January 12, 1987. Following its usual playbook of associating major theme park attractions with real-world pioneers, Disney’s PR team invited astronauts Gordon Cooper and Deke Slayton to the launch event. But in a twist, they also invited Rutan and Yeager, who were still making headlines.

A Dinner Conversation That Changed Advertising Forever

After the Star Tours opening ceremony, a private dinner was held with Disney CEO Michael Eisner, George Lucas, and Eisner’s wife, Jane. During the meal, Eisner asked Rutan and Yeager, “You just made history. You traveled non-stop around the planet on a plane without ever refueling. How are you ever going to top that, career-wise? What are you two gonna do next?”

Without hesitation, Jeana Yeager replied, “Well, after being cramped inside that tiny plane for nine days, I’m just glad to be anywhere else. And even though you folks were nice enough to fly us here, invite us to your party… Well, as soon as we finish eating, I’m gonna go over to the Park and ride some rides. I’m going to Disneyland.”

Jane Eisner immediately recognized the power of Yeager’s statement. On the car ride home, she turned to Michael and said, “That’s a great slogan. I think you should use that to promote the theme parks.” Like many husbands, Michael initially dismissed the idea, but Jane persisted. Eventually, Eisner relented and pitched it to his team.

The Super Bowl Connection

With Super Bowl XXI just around the corner, Disney’s PR team saw an opportunity. The game was set for January 25, 1987, at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena—just miles from Disney Studios. What if they convinced the winning quarterback to say, “I’m going to Disneyland” live on-air?

Disney quickly struck a deal with both quarterbacks—Phil Simms of the New York Giants and John Elway of the Denver Broncos—offering each $75,000 to deliver the line if their team won. Simms led the Giants to victory, making history as the first athlete to say, “I’m going to Disney World!” on national television.

A Marketing Triumph

That year’s Super Bowl had the second-highest viewership in television history, with 87 million people watching Simms say the famous line. The next day, Disney turned the clip into a national commercial, cementing the phrase as a marketing goldmine.

Since then, “I’m going to Disneyland” (or Disney World, depending on the commercial) has been a staple of championship celebrations, spanning the NFL, NBA, and even the Olympics. What started as a casual remark at dinner became one of the most successful advertising campaigns in history.

A Lasting Legacy

Jane Eisner’s keen instinct and Disney’s ability to act quickly on a great idea created a tradition that continues to captivate audiences. The “I’m going to Disneyland” campaign remains a testament to the power of spontaneous inspiration and smart marketing, proving that sometimes, the best ideas come from the most unexpected places.

To learn more about Disney’s ties to the world of sports, check out I Want That Too: A Disney History and Consumer Product Podcast.

-

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment9 months ago

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment9 months agoDisney’s Forgotten Halloween Event: The Original Little Monsters on Main Street

-

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment10 months ago

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment10 months agoThe Story of Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party: From One Night to a Halloween Family Tradition

-

Film & Movies9 months ago

Film & Movies9 months agoHow “An American Tail” Led to Disney’s “Hocus Pocus”

-

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment7 months ago

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment7 months agoDisney and Macy’s 90-Year Thanksgiving Day Parade Partnership: From Mickey’s First Balloon to Minnie’s Big Debut

-

Television & Shows5 months ago

Television & Shows5 months agoHow the Creators of South Park Tricked A-List Celebrities to Roast Universal – “Your Studio & You”

-

History5 months ago

History5 months agoThe Super Bowl & Disney: The Untold Story Behind ‘I’m Going to Disneyland!’

-

Film & Movies1 month ago

Film & Movies1 month agoBefore He Was 626: The Surprisingly Dark Origins of Disney’s Stitch

-

Podcast3 months ago

Podcast3 months agoEpic Universal Podcast – Aztec Dancers, Mariachis, Tequila, and Ceremonial Sacrifices?! (Ep. 45)