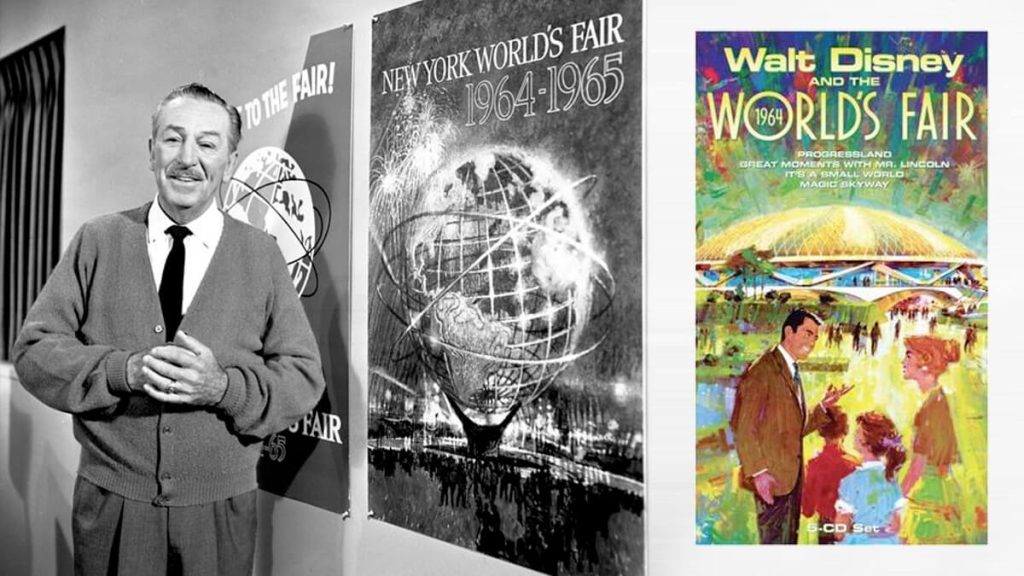

There has long been this legend about the importance the 1964 New York World’s Fair played in the history of the Walt Disney Company.

How the Fair was supposed to be this vital stepping-stone in the creation of Walt Disney World.

How Walt had to see if his theme park rides and attractions would meet with the approval of those East Coast sophisticates before he’d agree to buy all that land around Orlando.

It’s a nice story. Not true, mind you. But it’s a nice story nonetheless.

Truth be told, Disney operatives had already been scoping out property around Florida for at least three years prior to the Fair’s opening in April of 1964. Indeed, Disney’s chief purchasing agent — a lawyer named Bob Foster — made a big point of being seen publicly in New York for the opening festivities for the ’64 World’s Fair just before he slipped off to Orlando to pick up the options on 12,400 acres of property.

Why for? Just in case someone in Florida had recognized Bob and later asked him whether he’d been in Central Florida doing the Mouse’s bidding. Foster would then be able to deny the accusation by saying “Wasn’t me, pal. I wasn’t in Florida that week. I was in Flushing attending the Fair. I’ve got witnesses.”

New York World’s Fair Not the Birthplace of Walt Disney World?

So if the New York World’s Fair wasn’t really the birthplace of Walt Disney World, then why do Disneyana fans and theme park historians place so much emphasis and/or apply such significance to the Fair?

The answer is simple, really. So much of the technology that Disney developed to create the company’s break-through theme park attractions of the 1960s — “Pirates of the Caribbean,” “The Haunted Mansion,” etc. — were a direct result of Walt Disney Productions’ involvement in the Fair.

Walt, having already created a few small exhibits for earlier versions of the World’s Fair (the 1939 New York World’s Fair even featured a special Mickey Mouse cartoon — “Mickey’s Surprise Party” — that Walt personally put into production promoting the product line of the National Biscuit Company, AKA Nabisco), was already well aware of the opportunities that an exhibition like this would offer to a company like Disney.

Advancing WED by Partnering with the New York World’s Fair

Don’t believe me? Then take a gander at this transcript from a March 1960 meeting at WED Enterprises, where Walt tells his Imagineers about the opportunities that he sees in the recent announcement that there’s another World’s Fair held in New York in 1964:

“There’s going to be a big fair in New York. All of the big corporations in the country are going to spend a hell of a lot of money building exhibits there. They don’t know what thy want to do. They don’t even know why they’re doing it, except that the other corporations are doing it and they need to keep up with the Jones. Now they’re all going to want something that will make them stand out from the others, and that’s the kind of service we can offer them. We’ve proved we can do it with Disneyland. This is a great opportunity for us to grow. We can use their financing to develop a lot of technology that will help us in the future. And we’ll be getting new attractions for Disneyland, too. That will appeal to them. We can say that they’ll be getting shows that won’t be seen for two six month periods at the Fair. These shows can go on for five to ten years at Disneyland.”

Walt Disney – March 1960

You see? Walt saw the New York World’s Fair not so much as a chance to show off what his Imagineers were capable of, but more as a tremendous business opportunity. A way to connect with many of the corporate leaders of America by helping them develop entertaining attractions that would properly showcase their products at the Fair. Disney also saw the Fair as a means to an end, a way to move some of his company’s highly expensive dreams off the drawing board.

Advancing Audio Animatronics Through Sponsorship

Take – for example – Disneyland’s “Enchanted Tiki Room” attraction. Now keep in mind that this was back in the early 1960s, a time when the Walt Disney Productions was just beginning to experiment with audio animatronics. Walt desperately wanted to put this feathered floorshow into his Anaheim theme park.

But the guy who actually held the company’s purse strings – Walt’s brother, Roy – was reluctant to free up the millions that would be necessary to build a full-sized version of this then cutting edge robotic show for Disneyland.

That’s when Walt had a brainstorm. He’d agree to build the Tiki attraction for some poor company that was desperate to find a show to present inside their pavilion at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. Disney would then make sure that his company’s lawyers worked the terms of the contract with this other corporation so that

A) the pavilion’s sponsor would fully underwrite construction of the Tiki attraction and

B) once the fair was over, the Enchanted Tiki Room would automatically be shipped back to Anaheim and begin presenting performances there.

That way, Disneyland would get a brand new high tech attraction without the Walt Disney Company having to layout big bucks to build the thing.

It’s an ingenious sounding scheme, isn’t it? And here’s the intriguing part: It almost worked.

Walt Disney Productions and Coca-Cola spent most of 1962 going back and forth about whether the cola giant would underwrite the cost of creating an Enchanted Tiki Room attraction that would be presented as the centerpiece attraction at the company’s pavilion at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. In the end, the folks back in Atlanta decided that the price that Walt was asking was just too high. Which is why Coke opted to take a pass on Disney’s feathered friends.

Walt then supposedly tried to interest both the Gas Industry and GM in including the Tiki Birds as part of the entertainment offered at their World’s Fair Pavilion. When these two companies also passed on the project, Walt decided to bite the bullet and have Walt Disney Productions pick up most of the cost of creating Disneyland’s Enchanted Tiki Room. With a slight financial assist from Stouffers Foods, the Adventureland attraction opened in June of 1963 to great acclaim.

Birth of the Omnimover

Speaking of GM, the real reason that the auto making giant opted not to go with Walt’s Enchanted Tiki Room (or any other attraction ideas that the Mouse has put forward) is that — while the corporation had been negotiating with Disney — it had also been forming its own in-house World’s Fair exhibit committee. So in the end, the carmaker felt that they didn’t really need Mickey’s help to make a big splash at the 1964 World’s Fair.

But — as they closed out negotiations with Disney in late 1960 — GM officials reportedly jokingly remarked: “You know who you should really be talking to, Walt? The folks over at Ford. We hear that they don’t know what the hell they’re going to do when it comes to the Fair.”

This — as it turns out — was indeed the case. Which was why Ford jumped at the chance of having Disney create an exhibit for their company to display at the 1964 World’s Fair. By July 1961, the Imagineers were already on site in Dearborn, Michigan looking for ideas that they could possibly use in Ford’s Fair attraction.

Oddly enough, Disney didn’t discover any concepts for possible Fair attractions out of this particular trip to Michigan. But what they did get was an idea for a new theme park ride system. Observing how Ford started out with a half ton of molten metal, then moved that super hot pile of steel along a half mile long assembly line, only to have a finished car burped out at the other end of the factory, Veteran Imagineer John Hench wondered … could this same technology be used to move people?

That trip to Dearborn lead to the creation of Disney’s Omnimover system — the very system that the Mouse uses today to move millions of people each year through their “Haunted Mansion” attractions as well as along its PeopleMover system.

“The Ford Wonder Rotunda featuring the Magic Skyway”

Anyway … the first idea that Disney pitched to Ford was a “Symphony of America” ride, which would have taken Fair visitors on a simulated tour of the United States. Guests would have sat in Ford vehicles as they rolled past elaborate recreations of the Grand Canyon, the Everglades, the Sequoias, etc. Ford rejected this idea outright. Why? Because — back in those days — you didn’t tour America in a Ford. You saw “the U.S.A. in your Chevrolet.” So Ford didn’t want to do anything that might inadvertently helped its competition.

That’s where the Dinosaur ride idea came from. Veteran Imagineers Claude Coats, Marc Davis and Blaine Gibson were put in charge of the Ford project and then told to get as far away from the “Symphony of America” idea as possible. Which is why they decided to set the revamped Ford attraction in the distant past.

The end result; The Ford Wonder Rotunda featuring the Magic Skyway, which was a huge hit at the Fair. It was also a massive undertaking. At 275,000 square feet, Ford’s show building was easily the largest structure erected on Flushing Meadow. The 127 audio animatronic figures that lined the Magic Skyway’s ride track also made Ford’s show one of the more technologically complex shows presented at the Fair.

Indeed, Ford’s Wonder Rotunda — with its ambitious size and scale — could be considered the mother of such Disney mega-attractions as “Pirates” and many of Epcot’s original attractions like “World of Motion” and “Horizons.” And the dinosaurs featured in Epcot’s “Universe of Energy” should look very familiar to ’64 World’s Fair fans. They are the exact same figures — down to the creatures’ poses and actions — that terrorized visitors to Flushing back in ’64 and ’65. Minus a few minor cosmetic changes, of course.

“Carousel of Progress” at New York World’s Fair

This brings us to another Fair favorite: General Electric’s Carousel of Progress. Which, as it turns out, wasn’t originally developed for the Fair at all. The Carousel was actually envisioned as the centerpiece attraction of a late 1950s expansion of Disneyland’s Main Street U.S.A. area: Edison Square, a whole new land that would have celebrated the era when America was shifting over from gas street lamps to the electric light bulb for its primary source of illumination.

However, back in 1958, when this show was first pitched for the Anaheim theme park, the attraction’s trademark theater-go-round technology didn’t exist yet. Which is why Disney’s Imagineers envisioned audiences getting up and walking from theater to theater to view this six-act show.

By the way, this is the show that proves — beyond a shadow of a doubt — that progress is always on the move. After closing in NYC back in 1965, this New York World’s Fair favorite moved to Anaheim where it ran for several years. Then it was on to Orlando, where Carousel has been entertaining visitors at Walt Disney World’s Magic Kingdom since the mid-1970s.

I should warn you Carousel fans out there that Progress’ days appear to be numbered. Friends at Walt Disney Imagineering keep telling me the old G.E. show is soon due to get its plug pulled. How soon exactly? Perhaps as early as the Fall of 2002, when the Carousel would close to make way for an new interactive Tomorrowland ride. So — if you’d like to get one last peek at this ’64 New York World’s Fair favorite — now might be a good time to book that trip to Orlando.

“Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln” at the New York’s World’s Fair

Speaking of shows that weren’t originally created for the New York World’s Fair, let’s now take a look at “Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln.” What’s intriguing about this attraction — particularly given that a significantly revamped version of “Great Moments” just re-opened in Anaheim to significant acclaim — is that this isn’t the show that Walt really wanted to do. “Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln” is a significantly stripped down version of an attraction that Disney wanted to have debut at Disneyland: “One Nation Under God.”

This attraction was supposed to have been the centerpiece attraction of yet another expansion of Disneyland’s Main Street U.S.A. area: Liberty Street. This proposed Anaheim addition was to have celebrated America’s colonial period, featuring thirteen authentic period structures that were supposed to represent the original thirteen American colonies.

The “One Nation Under God” show? Well, if you ever saw the original version of Walt Disney World’s Hall of Presidents, you’ve seen “One Nation Under God.” However, due to the huge cost of mounting this particular production, Walt couldn’t afford to produce this show all on his own. Which is why he spent years trying to line up a corporate sponsor for this super-patriotic show. Unfortunately, none of the companies that Disney approached in the late 1950s / early 1960s bit on the high cost project.

Determined to finally line up a corporation to help underwrite this proposed Disneyland attraction, Walt has his Imagineers work up a full scale version of one figure from the show: Abraham Lincoln. Walt hoped that — once potential sponsors got to see one of these robotic presidents in the flesh (so to speak) — they’d immediately jump at the chance to be associated with this show. Ever the showman, Walt had his Imagineers set up a manually controlled version of the Lincoln robot that could stand up and shake the hand of any potential sponsor.

Finally, the right man got the chance to shake Abe Lincoln’s hand: Fair President Robert Moses. Moses was said to be ecstatic when he finally got to “meet” Mr. Lincoln, allegedly declaring that “I won’t open the Fair without this exhibit.”

The only problem was that — like Walt — Moses wanted the big bells-and-whistles version of the show, “One Nation Under God.” So Robert personally began pursuing potential sponsors for the show. First off, he went after the folks with the deepest pockets … the United States Government. (The U.S. Government — after much hemming and hawing — had finally agreed to put up $15 million toward the construction of a federal exhibit for the 1964 New York World’s Fair in early 1962.)

Moses appealed directly to the Department of Commerce, the one office within the government with direct control over how the U.S.’s money would be spent at the fair. He met personally with the undersecretary of Commerce — Franklin Deleanor Roosevelt, Jr. — to try to get his office behind “One Nation Under God” show. In the end, the U.S. Government — though impressed with Disney’s proposed presentation — felt that a show that featured “talking doll” versions of our Commanders in Chief might be viewed by some as being demeaning to the office of the President. So they opted to pass on the project.

Now it’s been suggested that FDR Jr. — who allegedly felt that a robotic version of his dad would be extremely disrespectful — personally put the kibosh on the Government picking up the tab for the “One Nation Under God” show. Well, while I had heard this story from literally dozens of former Disney Productions employees, no one’s ever been able to provide me with definitive proof on this matter. So — until that proof turns up — I’m afraid that we’re just going to have relegate the “FDR Jr. killed ‘Hall of Presidents’ for the ’64 World’s Fair” story to the urban legends pile.

Moses refused to give up, though. He kept pursuing potential sponsors for the “One Nation Under God” / “Hall of Presidents” show until December 1962. Robert even appealed to Coca-Cola, which — after passing on presenting Disney’s “Enchanted Tiki Room” — was still in search of an attraction for the Fair. Hoping to finally close the deal with Coke, Disney supposedly had the delicate Lincoln figure shipped all the way from Burbank to NYC to give a demo to Coke’s CEO.

Unfortunately, the Chairman of Coca-Cola — while riding into the city to see the Lincoln demonstration — was supposedly insulted by a bunch of African-American teenagers who were riding in an open car next to his limo. This supposedly put the CEO in a foul mood that morning. Which — according to Robert Moses’ autobiography, “Public Works: A Dangerous Tale” — is the reason that Coke ultimately decided to pass on sponsoring this project.

Things were looking pretty bleak for the electronic Honest Abe until the state of Illinois entered the picture. Illinois — which didn’t even get around to putting together the funding necessary sponsor an attraction at the 1964 New York World’s Fair until early 1963 — was desperate to find some sort of show to present at the Fair. Disney and Moses were desperate to find someone to sponsor their “One Nation Under God” show. In one of those great “You’ve got Peanut Butter in my Chocolate” moments, these three came together and — Presto Change-o — Lincoln finally had a sponsor.

Unfortunately, given the limited amount of prep time left until the Fair opened, Abe would NOT be appearing alongside the other Chief Executives. Why for? Because Disney just didn’t have time to build AA versions of all of the other Commanders in Chief. Which is why Lincoln ended up doing a solo act — his “Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln” show.

Of course, give that Disney got a late start on the “Great Moments” show, it just makes sense that the robotic version of our 16th president didn’t debut with the rest of the Fair on April 20th. Due to all the hassles associated with the rushed production, Lincoln didn’t officially open to the public until two weeks later, May 2, 1964.

As you probably already know, the finished version of “Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln” was a complete smash. Walt was proud, but not prouder than Moses — who had worked like a champ for nearly two years to find Disney’s remarkable Lincoln figure a home at his Fair. How proud was Robert of this particular exhibit? Years after the 1964 New York World’s Fair closed, Moses was often heard to say “My two greatest accomplishments at the Fair were Michaelangelo’s Pieta and Disney’s Lincoln.”

“It’s a Small World” Attraction at the New York’s World’s Fair

But — at least from Walt’s point of view — Walt Disney Productions’ greatest accomplishment at the Fair had to be its high-speed creation of the “It’s a Small World” ride. After all, this was a show that no one thought would happen, let alone work.

You see, Pepsi-Cola was working with Unicef — the United Nation’s Agency for Children’s Welfare — to come up with an attraction for the Fair that would salute Unicef as well as pay tribute to all the children of the world. After months of floundering, the creative staff at the cola giant finally had to admit to management that they were stumped. They just couldn’t come up with a workable concept for a Unicef show for the Fair.

It was at this point that somebody finally said, “Let’s call Walt Disney.” After all, given Walt Disney Productions’ reputation for turning out fine family entertainment, it just made sense to the folks at Pepsi to approach Disney. After all, Walt and his staff were sure to be able to find a way to make this Unicef tribute show work.

The only problem is that Pepsi didn’t approach Disney about helping out with this project until April of 1963. Given the limited amount of time until the Fair opened, head Imagineer Joe Fowler politely turned the cola people away, explaining that there was just no way that Walt Disney Productions could get a full-scale attraction for the Fair designed and built in the amount of time that was left.

Which, as it turns out, was a mistake. When Walt got wind of what Joe had done, he was furious. Disney called Fowler into his office and basically read the man the riot act. “I’m the one who makes the decisions around here,” Walt allegedly roared. “So you call the Pepsi people back now and tell them that we’ll do their damned Unicef pavilion.”

Kind of ironic, isn’t it? That the only reason that “the Happiest Little Cruise That Ever Sailed ” (or so says Disney’s own press releases) actually exists is that someone made the mistake of upsetting Walt Disney.

Anywho … what’s truly fascinating about the story of the creation of Disney’s “It’s A Small World” is how much of what this now beloved attraction is today was determined by how quickly the project was slapped together. How so? Well, a lot of the layout and design of the finished version of “Small World” was due to the fact that the Pepsi Cola ride building for this attraction was actually under construction before anyone knew for sure what was going to go into the structure. That’s why the folks at the Fair just threw up a simple L shaped building with 32,000 square feet of space inside. Those who actually worked on the attraction called it “the ugliest building you ever saw in your life.”

(Perhaps recognizing that the Pepsi Cola building wasn’t what you’d call attractive, Walt Disney asked veteran Imagineer Rolly Crump to come up with something to jazz up the front of the “small world” structure. Distract people from seeing how boring the building really was. That’s when Rolly came up with the Tower of the Four Winds, a colorful but complex array of mobiles that stood over the entrance to “Small World.” Which, in the end, proved to be a brilliant plan. Crump’s mobile is now remembered by many as one of the more charming things they saw while touring the Fair. But almost no one remembers how boring the exterior of the Pepsi Cola building was. Anyway…)

It was until after the foundation had been poured and steel was flying up that Walt decided that he wanted some sort of boat ride to run through the Pepsi Cola building. So — working with the L shaped boundaries of the building — the Imagineers quickly roughed out a floor plan for a ride that would pay tribute to all the children of the world. Only — in the original version of the attraction — the children were all supposed to be singing the national anthem of each of their individual countries.

An early test on the Disney lot proved that this idea was a complete disaster. All of the national anthems sung simultaneously meant that the songs drowned each other out or — worse than that — bled together, making this unholy noise. That’s when Walt got the idea of grabbing the Sherman Brothers — Bob and Dick — and asking them to do a song for the show.

Best known today as the Oscar winning composers of the score for “Mary Poppins,” the Sherman Brothers had already contributed several songs for other Disney shows at the Fair. Remember “It’s a Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow” for G.E.’s Carousel of Progress? That was theirs.

Anyway, working off of Walt’s instructions, Bob and Dick quickly knocked out a roundelay, a song that could be sung as a round by the robotic kids with an occasional counterpoint. Sticking a temporary title on the tune of “It’s a Small World After All,” they dropped their first draft of the song on Disney’s desk — apologizing for the song being so silly and simple. They promised their boss that they’d come back with something more musically complex sometime later. Walt wouldn’t hear of it. So the thrown-together tune that the Sherman Brothers delivered to Walt Disney that afternoon in late 1963 is the very same song that we can’t get out of our heads — no matter how hard we try — 38 years later.

Successful Showing by Disney at the New York’s World’s Fair – But a Few Difficulties

Luckily, all of this hard work by Walt’s Imagineers paid off. All four of Disney’s shows for the Fair received enormous acclaim. Indeed, in some surveys that were taken to gauge the popularity of various shows and attractions at the 1964 New York World’s Fair, Walt’s shows often took four of the top five slots. Attendance-wise, “Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln,” “It’s A Small World,” “Carousel of Progress” and “The Magic Skyway” always made it into the top 15.

Of course, it’s not like Disney didn’t have a few difficulties with its attractions during their days at the Fair. For example, Mr. Lincoln had to have his glass eyes and false teeth repaired repeatedly. Why for? Because some guests at the Fair became convinced that there was just no way that this lifelike figure could be a robot. So — in an effort to prove that Disney’s Lincoln figure was really just a guy in a suit — these folks used to whip the free ball bearings that they’d pick up the SKF exhibit at the Honest Abe AA figure. Hence the cracked eyeballs and the chipped false teeth.

The “Small World” attraction also had to deal with periodic damage caused by pranksters. Not-so-nice New Yorkers were forever stealing fish out of the Koi pond at the Japanese pavilion and slipping the colorful creatures into the immense water-filled trough that ran through the Pepsi Cola show building. That is, of course, when they weren’t emptying entire bottles of Mr. Bubble into the water … which would result in the boats having to push through 4-foot high walls of foam.

Disney also wanted to have some of the company’s rubberheads – you know, those full-sized costume characters that regularly meet-n-greet tourists at Disneyland and Walt Disney World – make daily appearances in front of the Pepsi Cola Building. However, after Snow White had a switchblade pulled on her and Practical Pig had his arm of his costume torn off, Disney’s rubberheads suddenly began greeting guests at the Fair from above – waving down at the people standing in line at “It’s A Small World” from a platform that was fixed to the bottom-most portion of the Tower of the Four Winds.

Moving the Attractions to Disneyland

True to his word, Walt tried to get all four of the exhibits that Walt Disney Productions produced for the Fair brought back to Disneyland. To that end, Disney was about 75% successful.

He got “Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln” and the “Carousel of Progress” brought back to Anaheim virtually unchanged. “It’s A Small World?” Well, the ride made it back to Disneyland … but not the Tower of the Four Winds. As charming as this immense mobile might have been, Walt balked when he learned about the projected cost of dismantling the tower and having it shipped back to California.

Which is why — after the Fair closed — the Tower of the Four Winds was unceremoniously pulled down. The all-metal structure was chopped into itty, bitty pieces using acetylene torches, then tossed into the Flushing Rive The Tower’s final resting place? I keep hearing that most of it ended just offshore of the Fair’s Lakeside Amusement area / Transportation Zone. Anyone up for mounting an underwater salvage operation?

Ford’s Magic Skyway? Well, given the size of the thing, there was just no way that the entire attraction was going to make it back to Anaheim. Walt settled for just the dinosaur AA figures, which he then tacked on the park’s “Grand Canyon” diorama as a trip through the “Primeval World.” This sequence has been serving as the grand finale for the grand circle tour of Disneyland aboard the park’s steam locomotives for almost 35 years now.

More Disney at the World’s Fair?

Of course, these are the sorts of stories that any dedicated Disneyana fan could already tell you about the company’s involvement in the New York World’s Fair. But one of the more intriguing but least well know aspects of Disney’s tenure at the Fair was — after the 1964 season closed and the billion dollar extravaganza hadn’t even come close to meeting its attendance projections — Moses supposedly met with Walt and asked for his help in driving up attendance for the 1965 season. Robert allegedly proposed a new Disney-designed amusement area, which would have been built on a large vacant piece of land next to the gas pavilion. Moses reportedly envisioned a miniature Disneyland, complete with castle and dark rides. Walt politely refused Robert’s request.

Why for? Well, maybe it was because Disney knew that Moses was skating on thin ice at that point. As 1965 and the Fair continued to fall behind its financial projections, a movement was started to oust Moses as head of the Fair. And whose name was on the short list to take over Robert’s position as President of the Fair. You guessed it, folks: Walt Disney.

When approached about the position, Walt again supposedly politely refused. Why? Probably because his top secret Florida project was already well underway. So why waste time trying to find ways to improve attendance at Flushing Meadows when there was a whole new world to be carved out of the swamps of Florida?

Of course, even though Walt turned down the job as President of the Fair, that didn’t necessary mean that he wasn’t above raiding the Fair’s staff to help run his own organization. That’s why Walt hired away Robert Moses’ right hand man, General William E. (Joe) Potter (USA, ret.) as the Fair was winding down.

General Joe Potter

Who’s General Joe Potter? Well, prior to his time spent working with Moses, Potter spent many years working with the Army Corps of Engineers. Joe was a man who accustomed to taking on big jobs and getting them done. At one point, Potter had actually been governor of the Panama Canal Zone.

After watching Potter masterfully ride herds on the construction of the dozens of different pavilions that were rising up out of Flushing Meadow, Walt knew that Joe was exactly the guy he needed to help turn all those cypress swamps in Florida into a vacation paradise. Which is why — as the Fair was drawing to a close in late 1965 — Disney offered Potter a position with the Disney organization.

In the end, Potter was the man responsible for turning the 28,000 acres of Florida swampland that Disney had purchased outside of Orlando into a workable construction site. Starting in July 1967, Joe and his staff dug 44 miles of canals. Potter’s crew also drained the 450-acre Bay Lake, scraped the bottom clean, refilled the lake, then move 9 million cubic yards of earth to create a nearby lagoon. This monumental effort led to the creation of the scenic centerpiece of the Magic Kingdom Resort area: Seven Seas Lagoon.

So who knows if Walt Disney World would have become the enormous success it is today if Gen. Joe Potter hadn’t been available to help carve this vacation paradise out of the Florida wilderness. Of course, Walt probably wouldn’t have even met Joe if the Disney organization hadn’t done all those shows for Robert Moses and his 1964 New York World’s Fair.

So — in the end — I guess maybe the Fair WAS actually the vital stepping stone in the creation of Walt Disney World. But just not in the way you might have thought that it was.