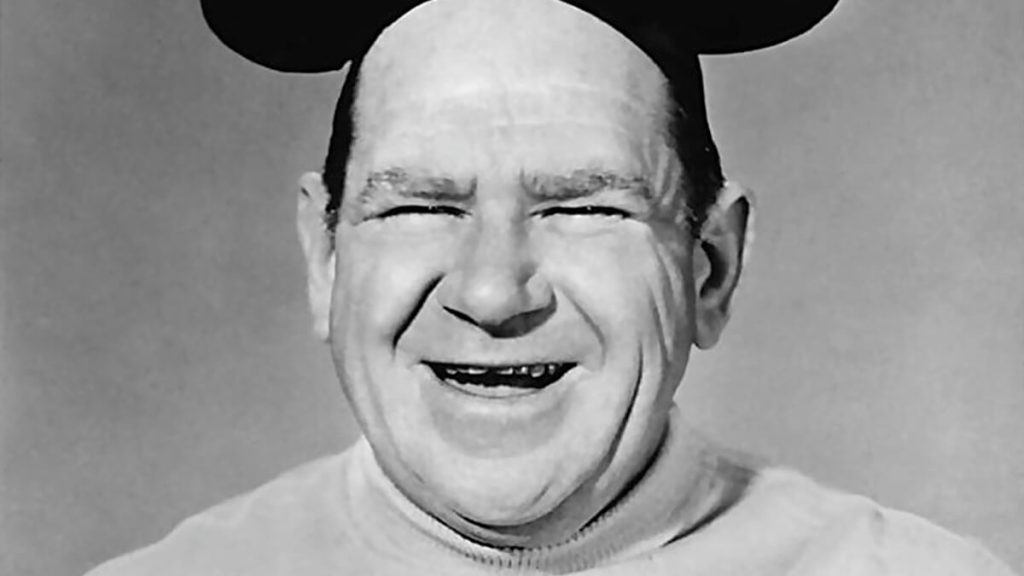

Like many kids, I was intrigued by Roy Williams on the Mickey Mouse Club. He seemed huge and perhaps a little slow on the uptake compared to the slender and perky Jimmy Dodd. I don’t know what really bothered me. Did I fear he would eat one of the Mouseketeers or go on a killing rage or sit and crush Jiminy Cricket before the little insect could spell “encyclopedia”?

Roy Williams was born on July 30, 1907. He was hired by Walt Disney in 1930 when he was 23 years old. When Roy first applied for the job, he began talking with who he thought was an office boy because he was young and shifting through some papers on the boss’s desk. The young boy turned out to be Walt Disney himself.

A lot of legends surrounded “Moose Williams,” his nickname as a former high-school football star. Director Jack Kinney remembers Williams walking on top of the canvas roof of a convertible car and falling through into the driver’s seat. Roy was quite a rough and tumble fellow and if I didn’t know that “Big Al” in “Country Bear Jamboree” was inspired by storyman Al Bertino, it would not be hard to imagine Roy as the model for the character.

He was personally chosen to be the Big Mooseketeer by Walt Disney. “I was scared to death….I was no actor but I had faith in Walt’s vision. One day Walt walked into my office and said, ‘Say, you’re fat and funny lookin’. I’m going to put you on the Mickey Mouse Club and you can be the Big Mooseketeer’.”

When I got my autographed (nude) photo of former Mouseketeer Doreen Tracy at a local convention, she told me that Roy hosted parties for the Mouseketeers in his backyard and they loved him since he was so playful and protective. Apparently he did tell dirty stories to the boys off camera and Doreen claimed that she helped hide his liquor bottles on the set so he could drink undiscovered when he got bored during rehearsals.

It was Roy who came up with the design for the famous Mouse ears hat. He was inspired by a gag in the 1929 Mickey Mouse short “The Karnival Kid” where Mickey quickly tips his ears like a hat to Minnie.

Roy worked for the Disney organization for many years following the end of the show until his retirement. Roy died on November 7, 1976, the victim of a heart attack. “Ever a colorful character,” reported the Motion Picture Screen Cartoonists Newsletter, “Roy stipulated that he, much to the astonishment of morticians, but not his many friends, be interred wearing his Mickey Mouse Club hat and his Mickey Mouse Club t-shirt, with his name inscribed on the front thereof, in full regalia.” If Bela Lugosi could be buried in his Dracula cape, it certainly seems appropriate that Roy would be buried with his famous mouse ears.

“The Secret World of Roy Williams” was a Bantam Books paperback published in 1957 with a caricature of Roy on the cover. The back cover blurb declared:

“Here’s a great big guy who spends his days wearing a mouse hat and drawing cartoons for kids. What do you suppose he thinks of…when the kids are asleep?..All the day he’s the big Mooseketeer–(Mouseakartooner), All day he’s drawing mouses, meece and mice. All day he’s three hundred pounds of walking pixie. And then he folds up the Mousekartoon Klub and the kids turn off the tv and go to sleep…and it’s night time. He sneaks back to his drawing board and goes quietly mad, deliriously daffy, blatantly funny…inside..the secret world of Roy Williams”.

It is no secret that Roy Williams spent most of his life working as a gag man at the Disney Studio. He was more of a gag man than a story man. One Disney animation director told me that Williams was more of a “spot gag” man. He could come up with a funny isolated visual but he couldn’t expand it into a story. As a gag artist, Williams was very fast. He often showed up at story session with hundreds of drawings but only a very small percentage were useable. Williams was very fast as a gag artist. When the Mickey Mouse Club was on the air, Williams as the Big Moosketeer would spend weekends at Disneyland and churn out hundreds of quick sketches of Mickey Mouse and other Disney characters for eager children.

It is no secret that Williams enjoyed doing these quick sketches just as he obviously enjoyed working for Disney. His book is dedicated “To the man who has meant the most to me in faith and inspiration: Walt Disney, whose patience and guidance through a lifetime of association are in greatest degree imaginable responsible for the best of Roy Williams.” Hard to imagine a stronger dedication than that mouthful! Williams also had a hardback collection of his cartoons, “How’s the Back View Coming?” dedicated to singer Rudy Vallee and with a forward by Jerry Colona where he talks about meeting Williams at the Disney Studio during the making of “Make Mine Music”. This hardcover edition was published by Dutton in 1949. Williams’ cartoons appeared in “The New Yorker”, “Saturday Evening Post”, “Collier’s”, “American Legion”, “This Week”, “True” and “Liberty” just to name a few markets.

Williams was apparently popular or at least prolific and persistent to appear in so many highly competitive markets. His artistic style lacks “line weight” and his faces are surprisingly unexpressive for an artist whose gags often depend upon facial reactions for their effectiveness. Williams is a “soft” cartoonist. There is no malice in his work and unfortunately provokes an occasional grin rather than a laugh. His line work is wobbly and characters’ eyes are usually two black dots with the eyebrows either pointed down for anger or up for a more whimsical expression.

Only one cartoon in the “Secret World” has a Disney reference. A panhandler uses a Davy Crockett cap to solicit contributions. The other cartoons in the book? A boss says “Smithers you’ve got an eye for business.” And Smithers stands there with one of his eyes replaced by a dollar sign. A parrot keeps repeating “Polly wants a cracker” while the annoyed pet shop owner lights a fire cracker with glee to give to the unsuspecting bird. (Cracker, firecracker, get it?)

Another cartoon shows a young boy in a fishbowl type space helmet and in full spaceman gear with a space gun in his hand. He is eyeing a fish in a fishbowl. Yet another shows a woman leaving a supermarket with not a dog on a leash but a kangaroo who carries all the purchases in its pouch. Another shows a man turning a handle at an outdoor well and the rope pulls up not a bucket but a man in a diving suit.

Apparently, Walt and Roy pulled Roy aside and asked him not to submit any more gag cartoons to magazines because he might be giving away his best stuff that could be used in the Disney animated shorts. They needn’t have worried. I have also heard that Williams published a book of his poetry shortly before his death but I have never run across a copy if it was published.

Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse Club Magazine for December 1956 (Vol. II, No. 1) had the short article “Tips on Magazine Cartooning” by Roy Williams. For historical purposes, I am reprinting it here. Mickey Mouse Club Magazine is a treasure trove for Disney fans with articles credited to Bill Peet, *** Huemer, Charles Shows and even Roy E. Disney (who wrote about animals). Obviously these pieces were highly edited for the publication but the basic material must have come from these Disney writers.

I wonder how many aspiring cartoonists were encouraged by Williams’ words:

“Hi Mouseketeers! Many times your hobby will be the foundation for your lifetime work, and in twenty-five years at the Walt Disney Studio my hobby has been much like a busman’s holiday–he’s the fellow who takes a bus ride on his day off. At the studio we draw Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Goofy and all the other Disney characters, and on my day off I draw, in my home studio, cartoons for the magazines.

“If your hobby happens to be drawing, or if you just happen to be artistically inclined, perhaps you’ll find that you can develop your talent to make someone smile or guffaw through the medium of your cartoons. Now every magazine has a cartoon editor who is constantly on the lookout for funny cartoons and a new style of drawing. So here’s how you go about being a magazine cartoonist.

“First, the idea or subject is the important thing. You’ll see funny situations everywhere, and you’ll hear funny sayings, too. But so you won’t forget them, you should always carry a pad and pencil and jot them down. When you get to your drawing board you turn your humorous idea, stimulated by the notes you have made, into a rough cartoon sketch.

“You should draw this rough sketch on standard size (8 1/2 by 11 inches) white typewriter paper. You should make the sketch with black India drawing ink, using any type of pen that “feels” good to you. In this way you’ll develop your own original drawing technique. The reason you should prepare all roughs in black ink, instead of pencil, is that many editors will take them ‘as is’–by that I mean in their rough stage–for publication. “Black is necessary in the reproduction of your cartoon, and if an editor wants you to do a ‘finish’ he’ll mail the rough sketch back to you with complete instructions as to size, etc. I have found that most cartoon editors prefer that the vertical way of the paper be used when you draw roughs. If your cartoon has a caption you should print it under the cartoon in blue pencil. You should send the editor from five to fifteen rough ideas every time you submit anything, in order to give him more of a choice in picking out one of your cartoons.

“Those that don’t sell to one magazine you mail out to another as soon as you get them back. In this way, you’ll always have a lot of cartoons ‘working for you’. Here’s another important thing: always accompany your batch of cartoons with a self-addressed stamped envelope to insure safe return. So now you’re ready to try your hand at becoming a magazine cartoonists. Remember one picture is worth a thousand words but one picture, well-staged, might well be worth a million laughs.”