Film & Movies

Why For was Michael Clarke Duncan’s Grizz character cut out of Disney’s “Brother Bear” ?

Danielle F. wrote in yesterday to say:

I really enjoyed today’s story about Luigi’s Flying Tires

and like the idea of you turning Why For into a daily feature at your site. I

just hope you get sent enough questions

to actually make this happen.

And speaking of questions: I was sorry to hear that Michael

Clarke Duncan died today. I don’t suppose that you have any Disney-related

stories that you can tell about him?

Tom Hanks and Michael Clarke Duncan in “The Green Mile.” Copyright 1999 Warner

Bros. / Castle Rock Entertainment. All rights reserved

First off, I just wanted to say — to the friends &

extended family of this Oscar-nominated performer — that the staff &

readers of JHM are genuinely sorry for your loss. Michael was literally &

figuratively a huge talent. And to lose someone like this at just 54 years of

age is … Well, tragic.

But that said … Yeah, I do have a Disney-related story or

two to share about Mr. Duncan. And these have to do with Walt Disney Animation

Studio‘s 2003 release, “Brother Bear.”

If I’m remembering correctly, it was back in 1997 when I

first heard that Michael Eisner had suggested to the powers-that-be at

WDAS that they put a movie about bears in development. To be specific, Michael

wanted the animators there to use Shakespeare’s Macbeth as their inspiration

for a film which should be set in the forests of the Pacific Northwest.

(L to R) Director Bob Walker, Rick Moranis & Dave Thomas [The ‘SCTV” vets who

voiced moose brothers Rutt & Tuke in “Brother Bear”], producer Chuck Williams

and director Aaron Blaise. Copyright Disney Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved

Which — I know — at first glance, seems kind of like a

nutty idea But you gotta remember that “The Lion King” had been a

huge hit for the Company back in 1994. And given that that animated feature —

over the course of its very troubled production — had kind of backed into

“borrowing” the story structure of Shakespeare’s Hamlet (i.e. The

brother of the King first engineers his demise and then assumes the throne. And

it’s up to the King’s hesitant son to set things right / restore the kingdom)

… Well, given that WDAS was hoping that history would repeat itself with its

next animal-based, full-length animated feature, “borrowing” from the

Bard when it came to possible story ideas for “Bears” (FYI: That was

the original title of this movie. Just plain “Bears”) only made

sense.

So Aaron Blaise was tapped to be this project’s first

director. And over time, Aaron was joined by Bob Walker (who eventually became Blaise’s

co-director on “Bears”) and Chuck Williams (who WDAS vet Pam Coats

had recruited to become this film’s producer).

And for the next three years or so, whenever Nancy and I

visited with friends who worked at Walt Disney Feature Animation – Florida, as the

two of us walked through that studio, we’d see these amazing pieces of “Bears”

concept art (many of which drew their inspiration from Albert Bierstadt’s

landscape paintings of the American West). But then when we’d go out to lunch

with friends who worked at WDFAF and ask them how work was going on “Bears,”

we’d hear these painful & protracted tales about how Blaise, Walker and

Williams were still struggling. How Aaron, Bob and Chuck had come up with these

memorable characters and a colorful, evocative setting for their film. But what

this trio hadn’t yet found was a story.

Paul Felix’s concept art for “Brother Bear” ‘s northern lights / transformation sequence.

Copyright Disney Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved

Which sounds kind of weird, I know. But as Don Hahn (i.e. the

producer of “Beauty and the Beast

,” “The Lion King” and Tim

Burton’s soon-to-be-released stop-motion animated feature,

“Frankenweenie”) is fond of saying: “Sometimes you have to be right

in the middle of making a brand-new animated film before you then discover what

your story is actually about.”

But starting in 2000 or thereabouts, I began hearing that

“Brother Bear” had finally found its footing, That — thanks to

Michael Clarke Duncan (who had just come on board this project as the voice of

Grizz, this older male Grizzly that Kenai reluctantly befriends after he

undergoes his man-to-bear transformation) — this animated feature now had a

solid emotional center. That Duncan’s deep booming voice, his natural warmth

and good humor had made Grizz this character that audiences could immediately

relate to. And that — thanks to Grizz’s Falstaff-like physique and joie de

vivre (not to mention Michael’s terrific

vocal performance) — “Brother Bear” was going great guns now. That

WDAS seemed to have another

sure-to-be-“Lion-King”-sized hit on its hands.

But then a year or so later, I began to hear that

“Brother Bear” was being radically retooled. Again. More importantly,

that Grizz was now out as Kenai’s mentor & companion. And that — in the

latest version of the storyline for this Walt Disney Feature Animation –

Feature production — it was Kenai who was now going to be the reluctant mentor

/ father figure for Koda, this brand-new

character that the filmmakers had just come up with. Koda was this precocious,

motor-mouthed bear cub who was going to be voiced by Jeremy Suarez from

“The Bernie Mac Show.”

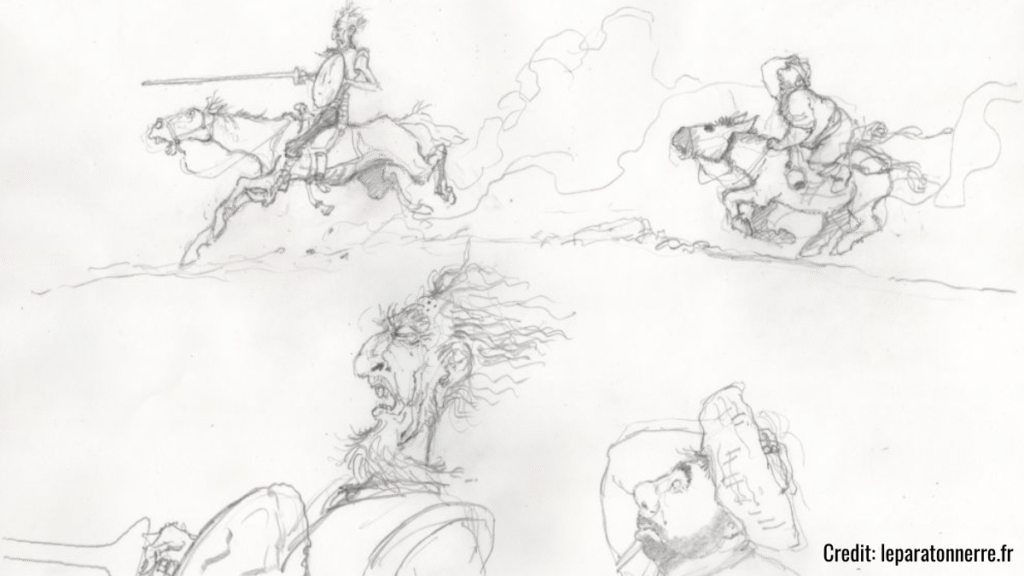

A storyboard for a scene from “Brother Bear” where Grizz was supposed to have

interacted with Rutt &Tuke. Copyright Disney Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved

“So what happened here?,” you ask. “If Grizz

was such a great character and everyone had been so in love with Michael Clarke

Duncan’s vocal performance, why then was Grizz cut out of ‘Brother Bear’ only

to then be replaced by cute little Koda?” To be blunt, Blaise, Walker and

Williams learned a hard lesson very late in the game during the production of

this animated feature. Which was that they had accidentally built their movie around the wrong character. That — when you

got right down to it — “Brother Bear” was about Kenai’s

transformation both inside & out. How this troubled teen finally grew up, learned

to be a better man by becoming a bear. And as long as Grizz was still in this

picture, with that oversized character serving as Kenai’s mentor (rather than

having Kenai learning about kindness, compassion & responsibility by

becoming Koda’s reluctant father figure), “Brother Bear” just wasn’t

going to work. At least as a truly satisfying piece of cinematic storytelling.

So Aaron, Bob and Chuck now had to call Michael and let him

know that he was no longer the big bear that this new Walt Disney Animation

Studios production was built around. Mind you, Duncan wasn’t completely out of

the picture. Blaise, Walker & Williams had so enjoyed Duncan’s vocal

performance as Grizz that they immediately found him a brand-new character to

voice in their film: Tug, the oversized Grizzly who’s the defacto leader of all

the bears at the salmon run.

And the way I hear it, Michael was very gracious to Aaron,

Bob and Chuck when he heard that the character of Grizz had been cut out of

“Brother Bear.” Even though this former body guard had only been in

show business for six years or so at that point, Duncan was enough of an

entertainment industry vet by then to know that these things happen. More

importantly, that it wasn’t personal. That WDAS was making these changes not

because they hadn’t liked his vocal performance. But — rather — because the Disney

Studio was just trying to make a movie that (they hoped) would eventually

connect with a very broad audience.

Copyright Disney Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved

And Michael clearly enjoyed doing voice work for animation.

Given that — on the heels of his “Brother Bear” experience — Duncan

would then go on to voice characters for feature-length theatrical releases

like “Dogs & Cats” & “Kung Fu Panda

” as well as

home premieres like “George of the Jungle 2” and “Air

Buddies.” Not to mention animated series for television like “Spider-Man,”

“The Proud Family,” “King of the Hill,” “Family

Guy,” “Static Shock,” “Teen Titans” and “Green

Lantern.”

So while it’s sad to think that Duncan’s basso-profundo voice

has now been silenced … At least we still have Michael’s previous work . The

obvious enjoyment that he got from performing, the real skill & craft that

Michael would draw from whenever he stepped in front of a camera or a

microphone.

And just so you know: Duncan isn’t the only performer who

found themselves — after months & months of standing in a recording booth,

voicing a character for a new Disney animated feature — who suddenly find

themselves out of the picture entirely and/or cast in a new role after that project’s

storyline had suddenly been retooled. Just ask Reese Witherspoon about all of the

voice work that she did on the character which was originally supposed to be

the lead in Disney’s “Rapunzel.” Likewise Holly Hunter about the

months she spent behind a mike, voicing the title character for Disney’s

“Chicken Little.”

The title treatment & concept art for Disney’s

“Chicken Little” from back when this film’s

title character was supposed to have been

a girl. Copyright Disney Enterprises, Inc.

All rights reserved

When I recently asked Penn Jillette about this (He was the

voice of Wolf-in-Sheep’s-Clothing, the original villain for Disney’s

“Chicken Little.” This character wound up being cut out of that animated

feature entirely when WDFA dropped this picture’s original sleepaway-camp-based

plot and opted to go with an aliens-fron-outer-space-invading

storyline instead), he was fairly philosophical about the whole matter:

“Look, I had a lot of fun working on that project. But

Disney’s been doing this for a long time. So you have to trust their judgment

when they say ‘This isn’t working. We’re going to take things in a different

direction and your character’s no longer part of the story that we’re trying to

tell here. So sorry about that. Bye.’ It’s nothing

personal. They liked my work and I liked working with them. It’s just show biz.

These things happen sometime.”

But even so … Well, I keep hoping that — what with all of

these loaded-with-extra-features Blu-rays that Walt Disney Studios Home

Entertainment has been releasing lately (Take — for example — that “Pocahontas”

Two-Movie Special Edition

that hit store shelves back on August 21st. This

Blu-ray actually includes a Special Feature where animation master Eric

Goldberg walks you through a lot of the storyboards & concept art that was

originally created for Disney’s aborted animated version of

“Hiawatha” from the late 1940s / early 1950s) — that the Studio will

eventually open up its vault and actually let us see what a “Chicken

Little” that was to have been built around Holly Hunter’s vocal

performance would have looked like. Likewise Reese Witherspoon’s take on

“Rapunzel.” And — of course — give us a glimpse of what Michael

Clarke Duncan’s performance as Grizz in “Brother Bear” (which — back

around 2000 — I heard was as much fun as watching Phil Harris’ work as Baloo

in Disney’s “The Jungle Book” was) would have been like.

Concept art for Grizz, the character that the late Michael Clarke Duncan

was originally supposed to have voiced in Disney’s “Brother Bear.”

Copyright Disney Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved

EDITOR’S NOTE: So far, we’ve been getting a very nice response to this week’s experiment of running Why For as a daily, rather than a weekly feature. If you’d like to see your Disney, animation or theme park-related questions answered on this website, please send them along to whyfor@jimhillmedia.com.

Film & Movies

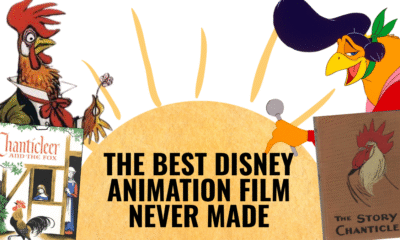

The Best Disney Animation Film Never Made – “Chanticleer”

This article is an adaptation of an original Jim Hill Media Three Part Series “The Chanticleer Saga” (August 2000).

Creating a “Don Quixote” Disney Animated Film

For over 60 years, Walt Disney Studios has been trying to turn Cervantes’ satiric stories about the Knight of the Rueful Countenance – “Don Quixote” – into an animated feature. Different teams of artists — in 1940, 1946 and 1951 respectively — have taken stabs at the material, only to be tripped up by the episodic nature of Don Quixote’s tale.

In the early 2000s, it looked like the Mouse might actually pull it off. For Disney had assigned Paul and Gaetan Brizzi — best known as the resident geniuses at Disney Feature Animation France — to tackle the project.

(I know, I know. There are a lot of really talented artists who work for Disney Animation. But — trust me, folks — the Brizzis really are geniuses. Do you remember that jaw dropping opening of “Hunchback of Notre Dame”? That was storyboarded by Paul and Gaetan. How about the “Hellfire” sequence from the same film? That was them too. And Stravinsky’s “Firebird Suite” in “Fantasia 2000”? Yep. That’s the Brizzis again. See what I mean? Geniuses …)

Well, Paul and Gaetan labored mightily for months on “Don Quixote,” turning out elaborate and immense storyboards for the proposed film. We’re talking huge pieces of conceptual art here, folks. Three feet by four feet, done all in pencil. Images that took the breath away of even the most jaded of animators.

But all this artistry was for naught. Management at Disney Feature Animation took a look at all the conceptual material the Brizzis had assembled earlier this year. Even though Paul and Gaetan’s storyboards were beautiful, the brass still took a pass on the proposed film.

Why for? A number of reasons, really. Cervantes’ stories — in spite of their fanciful images of windmills turning into giants and humble country inns becoming castles — don’t really lend themselves to animation. Don Quixote’s adventures tend to start and stop a lot. So it’s hard to turn a series of amusing anecdotes into a coherent dramatic narrative.

Plus the Brizzis take on the material? Intense. Dark. Very adult. Their version of the story actually frightened some of the suits in the Team Disney building. So Tom Schneider thanked Paul and Gaetan profusely for their efforts, then quietly pulled the plug on the project.

So all those great inspirational drawings by the Brizzis came down off the cork board, got carefully packed away, then sent off to the morgue … excuse me, “Animation Research Library” (ARL) … and got tucked away in a drawer someplace.

But that’s okay, folks. Because sometimes when they’re feeling creatively blocked, Disney animators will go down to the ARL and start burrowing through the files. What are they looking for? Images that startle. Drawings that inspire. Pictures that make you say “God, what a great idea! I wish I’d thought of that.”

Years from now, animators at the Mouseworks will be saying that very same thing when they come across Paul and Gaetan’s “Don Quixote” artwork. But do you know which conceptual art file Disney’s artists — top animators like Andreas Deja, even — request to see the most nowadays?

Would you believe it was for a Disney animated film that was to have featured fowl?

The Best Film Disney Never Made

Yep, nearly 40 years before Rocky and Ginger made their great escape in Dreamworks SKG / Aardman Animation’s “Chicken Run,” Disney proposed starring chickens in a feature length ‘toon. But these weren’t going to be common English hens. Walt was interested in exotic birds. Parisian poultry.

What was the name of this proposed film? “Chanticleer.” That name alone is enough to make animation historians sigh ruefully. Why for? Because this proposed animated film occupies a very unique spot in toon history. It may just be the best film Disney never made.

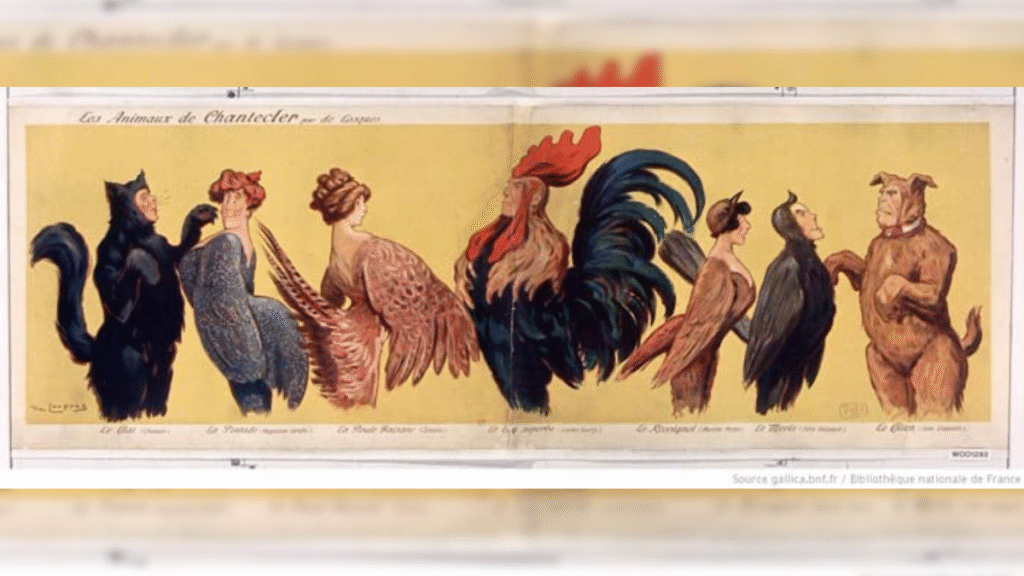

Source Material – “Chantecler” by Cyrano De Bergerac

What was the problem here? Well, to understand what went wrong with this proposed film, you have to go back to its source material: Edmond Rostand’s comedy, “Chantecler.” Edmond — best known today as the author of “Cyrano De Bergerac” — stitched together a slight story about a vain little rooster who thought that only his crowing could cause the sun to rise. Though it was set in a barnyard, “Chantecler” was actually a sly satire of pre-World War I French society bean. In spite of its satiric underpinnings (or maybe because of them) Rostand’s play became a favorite with European audiences — where it played to packed audiences for years.

“Chantecler” – 1937 Disney Project

Okay, now we jump to 1937. Walt Disney Studios is just about to finish work on their first feature length animated film, “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.” And Disney is casting about for ideas for the company’s next feature length cartoon when someone says “Hey, Walt. You ever hear of that play, ‘Chantecler’?”

Walt gets a quick run-down of Rostand’s plot and likes what he hears. He particularly thinks that the barnyard setting filled with farm animals will lend itself to lots of great gags for the movie. So Disney puts two of his top storymen — Ted Sears and Al Perkins — to work adapting the play to the animation format.

A few weeks later, Sears and Perkins get back to Walt with bad news. Try as they might, they can’t turn Rostand’s play into toon material. Ted and Al gripe that the pre-World War I satire will be too highbrow for American audiences. More importantly, they just can’t come up with a way to make the proposed film’s central character — the vain rooster, Chantecler — into a sympathetic character.

Walt then proposed folding the story of “Chantecler” in with another French fable the studio was toying with animating, “The Romance of Reynard.” This story — actually a collection of eleventh century European folk tales and poems — featured Reynard, a clever fox who was always tricking greedy nobles and peasants out of their ill-gotten gold. After all, what better way is there to make a vain rooster sympathetic than to give him a strong enemy? Someone like — say — a tricky fox?

So Disney’s story people took another whack at adapting “Chantecler” to the screen, this time using Reynard the Fox as the rooster’s enemy. (About this same time, folks at the Mouse House also americanized the name of the project. Which is how “Chantecler” became “Chanticleer”. Anyway …)

But even with the new villain on board, “Chanticleer” still wasn’t quite coming together. Sure, the barnyard setting and the farm animals featured in the story gave Disney’s artists plenty of funny stuff to work with. And they produced plenty of wonderful conceptual drawings for the proposed project. But — in the end — “Chanticleer”‘s story was still very weak and the main characters not terribly sympathetic. So, Walt reluctantly shelved the project.

“Chanticleer” Proposed Revivals

But — in the years ahead — Disney would periodically pull “Chanticleer” off the shelf and ask his artists to take another whack at the material. The project was revived no less than than three different times in the 1940s alone (1941, 1945 and 1947). In fact, many of the drawings done for the late 1940s version of the film provided inspiration for Disney’s 1973 animated feature, “Robin Hood” (Which — not-so-co-incidentally starred a clever fox that tricked greedy nobles out of their ill-gotten gold.)

Still, after all this effort, Disney had yet to turn “Chanticleer” into the makings of a successful animated feature. So — as the 1950s arrived — Walt decided to shelve the project for good (or so he thought). He then turned his attention to other more pressing projects — like Disneyland.

Marc Davis, Ken Anderson, and “Chanticleer”

Okay. Now we jump to early 1960. Ken Anderson and Marc Davis have just about finished work on “101 Dalmatians” and they’re excited. They know they’ve produced a film that really moved feature animation into the modern age. Both through its use of the Xerox process to transfer the animator’s drawings to cels as well as the film’s sketchy layout and design, “101 Dalmatians” is light years ahead of the studio’s previous feature, the stodgy “Sleeping Beauty.”

And the characters! Thanks to the Xerox process, the artistry and power of the lead animator’s original drawings really shines through now. That’s why Cruella seems so vibrant, so theatrical. That’s Marc Davis drawings in the almost raw you’re seeing up there on the screen there.

Marc was eager to build on the theatricality of Cruella. He wanted feature animation to next tackle a project that would allow Disney’s artists to really go for broke. Swing for the fences. Do something that would dazzle and entertain a modern audience.

So what did Marc have in mind? Davis — who was a huge fan of musical theater — wanted to do the animated equivalent of a big Broadway musical. Something with great songs and lots of colorful characters.

Does this sound familiar, kids? It should. Nearly 30 years later, Howard Ashman and Alan Menken actually pulled this off when they collaborated with Disney Feature Animation to create “The Little Mermaid.” That wildly successful 1988 film provided the template for all the animated projects that follow, “Beauty and the Beast,” “Aladdin,” et al. And here was Marc Davis — 28 years ahead of his time — trying to get Disney to do this very same thing. Life’s funny sometimes, isn’t it?

Anywho … So what does one base a big Broadway- style animated musical on? Well, Marc and Ken looked through all of the stories Disney currently had in development — but didn’t find anything that they liked. Which is how they ended up in the morgue … excuse me … “Animation Research Library” … looking at the studio’s abandoned projects.

That’s when Marc came across all the great concept art that had been previously done for “Chanticleer.” Looking over all these colorful drawings of chickens and Reynard the Fox, Davis had a brainstorm. He turned to Anderson and said “You know, I think we could really do something with this …”

But first they had to win Walt over to their idea.

Getting Walt’s Approval for “Chanticleer”

When Ken and Marc told Disney that they wanted to revive the “Chanticleer” feature idea, Walt was initially thrilled. After all, he’d been trying to make a movie made out of Rostand’s play for over 20 years at this point. But then Disney hesitated for a moment.

“What about the plot?,” Walt asked.

“No one’s ever been able to pull a decent cartoon out of this play yet. What are you two going that’s finally going to make this thing work?”

“Simple,” Marc said. “We’re not going to use the play. Ken and I aren’t even going to read the play. We’ll take the bare bones of the story and just make something up.”

It was a pretty audacious way to try and adapt a well-known story to the screen. But Disney loved the idea. (So much so that when the studio began working on a cartoon adaptation of “The Jungle Book,” Walt’s only advice to the story team — after tossing a copy of Rudyard Kipling’s book in the middle of the story conference room table — was to say “Here’s the novel. Now the first thing I want you to do is not read it.”)

Creating an Original Story for “Chanticleer”

So Ken and Marc holed up in an office at Disney Feature Animation for months, doing character sketches and playing with various story ideas. The first thing they did was abandon all the work that the studio had done previously on “Chanticleer.” Their hope was that — by getting a fresh start — they might be able to come up with something original: a light-on-its-feet satiric cartoon comedy. Something similar to Frank Loesser’s 1961 Broadway hit, “How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying” — a show that made a lot of clever, pointed jokes but never put them across in a mean spirited way.

Chanticleer – The Hero

The film’s hero had to be — obviously — Chanticleer, a well meaning but not terribly bright rooster. He — and all the other chickens that lived in his village — honestly did believe that the sun came up only because Chanticleer’s crowing awakened it every morning. The ladies of the village all swooned at the sight of the handsome young ***. The men in the village all wanted to be his best friend. (Think of Chanticleer as a kinder, gentler version of Gaston from “Beauty and the Beast.”)

In fact, Chanticleer is so well liked that the people of the village decide to elect him Mayor. Naturally, all that power goes to his somewhat empty head. So Chanticleer starts nagging the hens to produce more eggs … which — of course — annoyed the ladies.

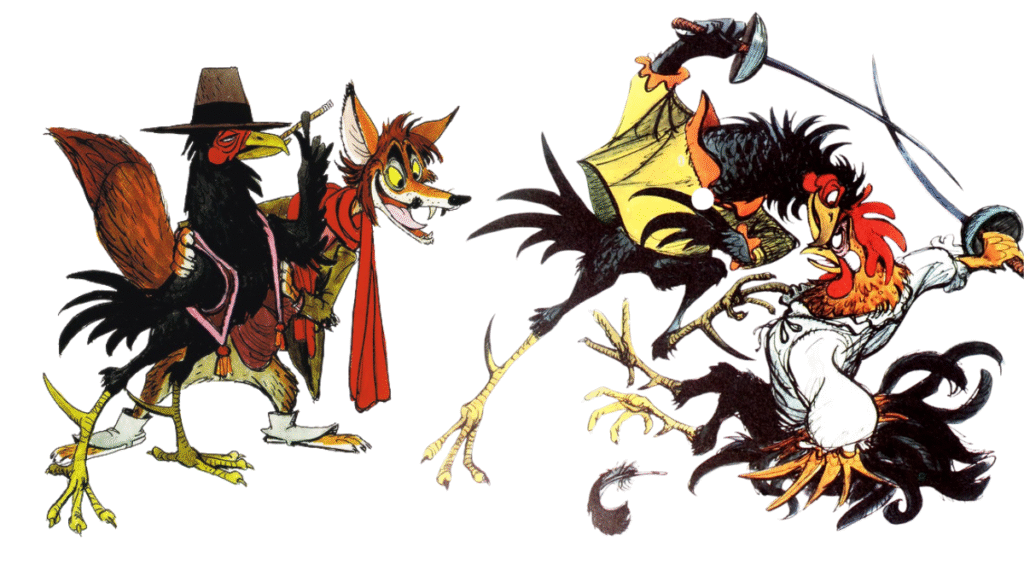

Reynard – The Villain

Enter the villain: Reynard the Fox. A shady character in a battered top hat, Reynard has a pencil thin mustache and continental charm. But behind those smooth words and those heavily lidded eyes, this fox is nothing more than a slick con artist — always playing the angles, always on the make.

The Plot of “Chanticleer”

Quickly sizing up Chanticleer’s sleepy village as a fruit — ripe for the plucking, Reynard sweet-talks some of the ladies of the village just so he can learn the lay of the land. The fox quickly ascertains that the chickens are unhappy under the rooster’s stern leadership and that the hens long to have a little fun.

That’s all Reynard has to hear. He slips out of town, only to return the very next day with his dark carnival. Run entirely by creatures of the night (owls, bobcats, moles, etc.) and birds of prey (vultures), the villagers have never seen anything like it. So the chickens stay up all night — singing, dancing and playing games of chance. When morning comes, the hens are entirely too tired to lay any eggs.

Chanticleer views the chickens’ behavior as civil disobedience, as a direct challenge to his authority. So he orders Reynard and his carnival to leave the village at once. The fox responds by saying that he thinks it’s time for a change in leadership in town. That’s when Reynard then announces that he’s running for mayor of the village.

Alright. I know. This doesn’t exactly sound like an award winning plot. And truth be told, it actually gets sillier from this point in: Chanticleer gets suckered into a pre-dawn duel with a Spanish fighting ***. (The Spaniard — as it turns out — is secretly working for Reynard.) Chanticleer is so busy trying not to get killed in this fight that he doesn’t notice that the sun has risen without his crowing that morning.

After the fight, Chanticleer realizes that he’s been a complete ass. He doesn’t control the sun anymore than he can control the other chickens in his village. Yet — because of his sincerity and newly humble nature — the villagers find it in their hearts to forgive him.

Working together, Chanticleer and the rest of the chickens rid the town of Reynard and his dark carnival. From that point forward, Chanticleer becomes the kind, good-hearted, thoughtful leader that the villagers had always hoped he’d be. Every morning, he still crows — not to wake the sun, mind you. But to wake his friends so that they can begin yet another day in their beautiful little French town.

Character Designs and Concept Sketches

Yes. Again, I know. The story sounds silly. Far too thin to support a feature length film. But what you haven’t seen are all the great characters Marc and Ken came up with to people this odd little story. Marc drew literally hundreds of concept sketches which show beautiful French hens decked out in their turn-of-the-century finery. Each of the villagers has a hat, coat or cape. Wearing glasses or clutching canes, they stare up at you — with their bright eyes and wide smiles — out of the concept sketches and seem to scream: “Animate me!”

These stylized characters — with their wonderful period costumes and stylized comic design — would have actually helped Anderson and Davis pull “Chanticleer” off. For Marc and Ken were really hoping to do something ballsy, something original with this film. They envisioned “Chanticleer” as an animated equivalent of a French farce. Something so light on its feet and fiercely funny that you never notice the elephant sized holes in the plot.

Music and Score for “Chanticleer”

Music too would have played a huge part in this film. Marc actually planned for the entire introductory sequence of “Chanticleer” to be done in song. Characters would have entered, literally lugging scenery to help set the stage for the show. Much in the style of Howard Ashman and Alan Menken’s “Belle” opening number for “Beauty and the Beast,” the villagers would have sung about Chanticleer:

“… We love him so, ’cause he brings the sun up, you know …”

Disney to Get Out of the Animation Business

The ironic part of all this was — as Marc and Ken were laboring to create a film that would move Disney Feature Animation into the 1960s — Disney’s accountants were trying to convince Walt to stop making cartoons entirely.

I know that nowadays – when an animated feature can make way over $100 million – it must sound strange that the Walt Disney Company had ever considered getting out of the animation business. But it’s true, kids.

At the time (1960 / 1961), Disney had already produced some 17 feature length animated films. Roy tried to persuade Walt that these were more than enough toon titles to adequately stock the studio’s film library. Studies had shown that Walt Disney Productions could release a different cartoon classics (“Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” “Pinocchio,” “Cinderella,” et al) each year and still make a healthy profit off the old movies. So there was really no sense in the company wasting any additional moneys making new animated films.

Shut Down Animation and Create Walt Disney World – Roy’s Attempt

Walt at first strongly resisted this idea. But Roy knew just what cards to play. He had heard that his brother was toying with building another Disneyland somewhere in the United States. Roy also knew that this park — which was supposed to be at least ten times larger that the original Anaheim project — was going to be expensive.

“You’d have all the money you needed to get started on your new park,” the elder Disney suggested, “if you just shut down feature animation.”

Walt again hesitated. For this was truly a tempting offer. All the money he needed to get started on his second park. Plus the cash necessary to fund the project that Disney was really interested in in those days: audio animatronics. Never mind that old, two dimensional stuff in “101 Dalmatians” and “Sleeping Beauty.” The three dimensional animated figures that Wathel Rogers and the other guys at WED were working on — the birds, that Chinaman’s head — that was what really intrigued Walt back then.

Disney had always been a forward thinking guy. He may have loved nostalgia, but he was also eager to tackle new projects, try new things. Compared to audio animatronics, animation did seem kind of old fashioned. But did Walt really dare to shut down Disney Feature Animation?

For weeks, the younger Disney debated the idea with his elder brother, Roy. In the end, Walt just couldn’t bring himself to do it. Walt Disney Productions’ financial security had initially been built on the popularity of the company’s animated movies. To stop making these fine family films entirely would just send the wrong message to the entertainment industry. So it just didn’t seem prudent to totally pull the plug.

Walt Agrees to Scale Back Disney

But what Walt did agree to do was to try scaling back animation production at the studio. Instead of a new animated feature every two years (the pace the company had tried to meet throughout the 1950s), Disney agreed to let Roy reconfigure things so that a new toon would come out once every four years.

The trouble was the studio currently had two animated films in active development: Bill Peet’s adaptation of T. H. White’s Arthurian fantasy, “The Sword and the Stone” and Marc Davis and Ken Anderson’s “Chanticleer.” To meet Roy’s new animation business plan, one of these projects was going to have to be shut down.

Guess which movie hits the cutting room floor?

Cancelling “Chanticleer” – “Sword and the Stone” Moves Forward

Without Bill Peet, Marc Davis or Ken Anderson’s knowledge, Walt brought himself up to speed concerning the current status of both projects. He did this by slipping into the animation building after hours, going into Peet, Davis and Anderson’s offices after they’d gone home for the day and examining all the pre-production art they’d produced for “The Sword in the Stone” and “Chanticleer.

After reviewing all of the conceptual material, Disney quickly came to one conclusion: In spite of the film’s heavy reliance on magic, it looked like “The Sword in the Stone” would be the easier (read that as cheaper) of the two films to produce. It was strictly a numbers thing.

- “Sword”‘s cast was smaller and mostly human — which made its characters easier to draw.

- That film’s story — though episodic in nature — also seemed to have a bit more heart than “Chanticleer.” Wart, from “Sword”, was an underdog that an audience could care about, root for. Chanticleer was … well … a pompous, preening rooster who thought the sun only rose because he crowed every morning. This was not exactly a character that an audience could immediately be expected to warm up to.

- “Sword in the Stone” had no elaborate musical numbers to stage, nor would its characters need big name celebrities to successfully voice their parts.

The final decision seemed like a no brainer. Bill Peet’s “The Sword in the Stone” would be the safer (read this also as cheaper) of the two films to produce.

So Disney would have to pull the plug on “Chanticleer.”

Telling Davis and Anderson

Now came the tough part. Walt was fond of both Marc and Ken. He knew that these guys had labored for the better part of a year in their attempt to turn “Chanticleer” into an animated feature. But Disney just didn’t have the heart to tell them that all of their hard work was for naught, that their film wouldn’t be going into production.

In the end, Walt couldn’t bring himself to tell Davis and Anderson that “Chanticleer” was canceled. So he didn’t. He let a member of Roy’s staff — with a mumbled aside — do the dirty work for him.

The Last Pitch Meeting

Marc knew he was in trouble the moment he saw where Walt was sitting.

Normally — at pitch meetings like this — Disney liked to be down front, dead center. Walt wanted to be as close to the action as possible, ready to leap up and act out a funny bit of business or quickly point out where the project had gone off track.

But Walt wasn’t sitting down front for the “Chanticleer” meeting. He quietly took a seat at the back of the room and avoided all eye contact with Davis and Anderson. The seats in the front row? They were all taken by “Roy’s Boys” — executives who worked on the financial side of the studio.

Marc and Ken quickly exchanged worried glances. But then, gathering his courage, Davis stepped to the front of the room and began his pitch for the proposed animated film.

No sooner had the phrase: “The hero of our story is Chanticleer, a rooster…” left Marc’s lips when one of Roy’s boys muttered to his co-horts: “A chicken can’t be heroic.”

Then Marc knew. 30 seconds into his pitch, “Chanticleer” was already dead in the water. All of Davis’s wonderful character sketches. All of Ken’s beautifully rendered backgrounds. None of that stuff mattered. This movie was never going to get made.

Still Marc pressed on — hoping against hope that he could win this audience over to the idea of doing an all-animated Broadway style musical that starred a chicken. No dice. The people attending this pitch session were polite but indifferent. For they knew what Anderson and Davis didn’t: That Walt had already canceled “Chanticleer.” He just hadn’t gotten around to telling them yet.

When the session was over, those in attendance shuffled out silently — not saying a word.

That includes Walt. Especially Walt.

Fallout from the “Chanticleer” Pitch Session

A week went by and Davis nor Anderson heard nothing from nobody. They just sat in their offices, shell-shocked at how badly the “Chanticleer” pitch session had gone.

Ken’s colleagues at Feature Animation gave these two a wide berth, avoided these two veteran animators like the plague. No one wanted to be associated with a development team that had failed that miserably in a pitch session for a proposed animated feature.

Only Davis and Anderson knew that they hadn’t really failed. They were certain that “Chanticleer” — as they designed it — would have made a wonderful animated film. Sure, it would have cost a bit more to make, taken a lot longer than “Sword” to produce. But audiences would have loved the finished product.

Only this time around, there wasn’t going to be a finished product. For some reason, the accountants — not Walt — were now calling the shots at Walt Disney Studios. And that meant an ambitious, expensive animated feature like “Chanticleer” was never going to make it off the drawing board.

What hurt most was not hearing from Walt. Walt — the guy who’d so strongly encouraged them to take this approach with the material. Walt — the guy who’d seemed so eager to get a “Chanticleer” movie made. Walt — the guy who sat in the back of that pitch session and didn’t say a word.

For a week, Marc waited by the phone — hoping that his boss would call and explain what the hell was happening. Why Roy’s Boys were suddenly deciding which features Disney’s animators could and couldn’t make.

Finally, the phone did ring. And — yes — it was Walt. But there was no explanation. No apology. Just a job offer.

Davis Gets a Job Offer at WED – No Mention of “Chanticleer”

“Marc,” Walt said, “Those guys at WED aren’t very good at staging gags. People have been complaining that Disneyland’s shows have gotten kind of humorless. Do you think you could go over to Glendale and help them out?”

That was it. No “I’m sorry I let the accountants torpedo your film.” No “You and Ken did a really great job. It’s just not the right time to make this movie.” No “That was the best work you guys ever did. I’m truly sorry that we can’t make this movie.” Just “Could you go over to Glendale and help those guys out?”

So Marc — because of his strong sense of personal loyalty to Walt Disney — went over to WED and helped those guys out. And he never returned to Feature Animation.

But — In the 17 years he stayed in Glendale working at Imagineering –Davis helped create some of the greatest theme park attractions the Disney theme parks had ever seen: “The Jungle Cruise.” “The Enchanted Tiki Room.” “It’s a Small World.” “Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln.” “The Carousel of Progress.” “Pirates of the Caribbean.” “The Haunted Mansion.” “The Hall of Presidents.” “County Bear Jamboree.” “America Sings.”

All of them great shows. Each of them displaying that distinctive Marc Davis touch.

But Marc never entirely forgot about “Chanticleer.” It was — to borrow a tired phrase that almost every angler uses — “the big one that got away.” The great film that would have really put a cap on his career as a master animator.

Ah, well … It wasn’t meant to be, I guess.

“Chanticleer” Nods, Easter Eggs, and References

Mind you, this didn’t stop Davis from folding characters and concepts he created for “Chanticleer” into his work at WED. Take another look at those singing chickens in “America Sings.” Do they look familiar? They should. Those birds belting out “Down by the River Side” are modeled after the feathered French hens would who have played the chorus in “Chanticleer.”

And it wasn’t just Marc that kept trying to recycle pieces of this proposed film. His character sketches for the aborted 1960s version of “Chanticleer” were so good, they quickly become the stuff of legends around Disney Feature Animation. Artists would repeatedly go down to the morgue (Excuse me. “Animation Research Library”), pull out the full color, beautifully rendered drawings Marc made for the movie and just marvel at them.

These drawings were so good — in fact — that veteran Disney animator Mel Shaw pulled them out in 1981 to try and sell Disney management on the idea that it was finally time for the studio to make “Chanticleer.” Hoping to improve the proposed project’s chances, Shaw worked up a story treatment that stressed the rooster’s heroic qualities — making him “the most MACHO (chicken) in all of France.”

Mel also threw together an inspiring set of pastel and watercolor conceptual drawings as he tried to sell the studio on making his vision of the film. But the folks running Walt Disney Productions in the early 1980s were more cautious and conservative then “Roy’s Boys” were back in 1960. They quickly shot down the idea of the studio ever doing “Chanticleer” as a full length feature.

When word got out that Disney had once again rejected the idea of doing “Chanticleer” as an animated feature, one man rejoiced. That man’s name? Don Bluth.

Don Bluth and Aurora Productions

Two years earlier, Bluth had made a very public break from the animation operation at Walt Disney Productions. Tired of the heads of the studio constantly cutting corners, always going for the safer choices, Bluth — one of the most talented young animators Disney Studio had at the time — bailed out of Burbank. He left his cozy corporate nest, taking 15 or more of Disney’s top young animators with them.

These folks started a new animation studio, “Aurora Productions.” Their mission: to make great animated films like Walt used to do. Movies like “Pinocchio” and “Bambi.” With strong storylines and full animation. Not tired, half-hearted films like “Robin Hood” and “The Aristocats.”

“The Secret of Nimh”

Right out of the box, Aurora Productions did make a great animated film. Maybe you’ve seen it … “The Secret of Nimh?” This film has everything a hit movie should have: A solid, moving story with superb animation. Characters you care about. Big laughs. Great action sequences. A beautiful score.

Yep, “The Secret of Nimh” had everything that a hit film should … everything except an audience. In spite of receiving tremendous reviews, “Nimh” really didn’t do all that well at the box office and quickly faded from sight.

But still — buoyed by those great reviews (as well as those encouraging phone calls from Spielberg and Lucas) — Bluth remained hopeful. Maybe someday — if he played his cards right — Don might get his shot at turning “Chanticleer” into a great animated film.

“Chanticleer” becomes “Rock-a-Doodle”

For — during his 10 year long tenure at the Mouse House — Bluth too had been down to the morgue (Aw … forget it!) and seen Marc’s drawings. That’s why he knew that a truly fine animated film could be pulled out of Rostand’s barnyard comedy.

10 years later, Don did get his chance at turning “Chanticleer” into a feature length animated film. And while it would be nice to report that Bluth did want Disney couldn’t: turned this French satire into a successful cartoon … that’s not exactly what happened, kids.

What went wrong? Well, for starters, Bluth’s version of “Chanticleer” — entitled “Rock-a-Doodle” — moves the story to America and turns this French vain rooster into … well .. sort of a feathered Elvis.

Then there’s the problem with the villain. Bluth knew that if he borrowed Disney’s proposed antagonist — Reynard the Fox — that it would be too obvious where he had cribbed his original source material from. So Bluth opted to create an all new villain for his “Chanticleer” cartoon: the Grand Duke (voiced by Christopher Plummer), an owl who wanted Chanticleer out of the way so that the sun would never rise again and the world would be forever shrouded in darkness.

Alright, so that’s exactly not the greatest motivation for a movie villain. There’s still lots to like about Bluth’s “Rock-a-Doodle.” Mouse fans will be pleased to hear that old Disney favorites like Phil Harris and Sandy Duncan provide voices for characters in the film. And — as a sly tribute to the original author of “Chanticleer,” Edmund Rostand — Don named the little boy/cat who drives the action in the movie Edmund.

Box Office Indifference for “Rock-a-Doodle”

Unfortunately, audiences in April 1992 (when “Rock-a-Doodle” finally made its stateside debut) weren’t feeling as kindly toward Don Bluth as I did. They greeted the film with indifference. “Rock-a-Doodle” got lousy reviews, did terrible box office and quickly sank like a stone.

So — since Don Bluth Productions turned out such a mediocre “Chanticleer” movie — that’s the end of the story, right? No one will ever again attempt an animated version of Rostand’s play, correct?

Not necessarily.

Andreas Deja

Modern Disney master animator Andreas Deja remains a huge fan of Marc Davis’ conceptual work for “Chanticleer.” In Charles Solomon’s great book about Disney animated features that never quite made it off the drawing board, “The Disney That Never Was,” (Hyperion Press, 1995), Deja is quoted as saying:

Marc designed some of the best looking characters I’ve ever seen — these characters want to be moved and used.

Deja’s obsession with this material continues. In April 2000 — as part of the “Tribute to Marc Davis” that was held at the Samuel Goldwyn Theater in Hollywood — Andreas took a few moments to show the crowd some of Marc’s drawings from “Chanticleer.” As he looked up at the images on the screen, Deja remarked:

It’s kind of sad that this movie was never produced; the studio decided to do ‘Sword in the Stone’ instead. Which is also a very good movie, but wouldn’t it have been nice to see these characters come to life? Apparently, at that time, the studio felt — according to Marc — that it would be too difficult to develop sympathy for a chicken. I don’t think so. I have sympathy for these guys.

Andreas Deja

He added, while still looking up at the pictures, “One of these days, I’ll have to sit down and do a few pencil tests of these characters — just to see them move.”

Maybe one day Disney will put together a test that finally convinces the accountants who are running the Walt Disney Company that there’s a great film to be made from Marc Davis’ “Chanticleer” conceptual material.

Here’s hoping, anyway.

Want more behind-the-scenes Disney stories? Dive deeper into the magic with Fine Tooning podcast, where Jim Hill and Drew Taylor explore animation news and history. Listen now at Fine Tooning on Apple Podcasts. For exclusive bonus episodes and even more insider content, check out Disney Unpacked on Patreon.

Film & Movies

Before He Was 626: The Surprisingly Dark Origins of Disney’s Stitch

Hopes are high for Disney’s live-action version of Lilo & Stitch, which opens in theaters next week (on May 23rd to be exact). And – if current box office projections hold – it will sell more than $120 million worth of tickets in North America.

Stitch Before the Live-Action: What Fans Need to Know

But here’s the thing – there wouldn’t have been a hand-drawn version of Stitch to reimagine as a live-action film if it weren’t for Academy Award-winner Chris Sanders. Who – some 40 years ago – had a very different idea in mind for this project. Not an animated film or a live-action movie, for that matter. But – rather – a children’s picture book.

Sanders revealed the true origins of Lilo & Stitch in his self-published book, From Pitch to Stitch: The Origins of Disney’s Most Unusual Classic.

From Picture Book to Pitch Meeting

Chris – after he graduated from CalArts back in 1984 (this was three years before he began working for Disney) – landed a job at Marvel Comics. Which – because Marvel Animation was producing the Muppet Babies TV show – led to an opportunity to design characters for that animated series.

About a year into this gig (we’re now talking 1985), Sanders – in his time away from work – began noodling on a side project. As Chris recalled in From Pitch to Stitch:

“Early in my animation career, I tried writing a picture book that centered around a weird little creature that lived a solitary life in the forest. He was a monster, unsure of where he had come from, or where he belonged. I generated a concept drawing, wrote some pages and started making a sculpted version of him. But I soon abandoned it as the idea seemed too large and vague to fit in thirty pages or so.”

We now jump ahead 12 years or so. Sanders has quickly moved up through the ranks at Walt Disney Animation Studios. So much so that – by 1997 – Chris is now the Head of Story on Disney’s Mulan.

A Monster in the Forest Becomes Stitch on Earth

With Mulan deep in production, Sanders was looking for his next project when an opportunity came his way.

“I had dinner with Tom Schumacher, who was president of Feature Animation at the time. He asked if there was anything I might be interested in directing. After a little reflection, I realized that there was something: That old idea from a decade prior.”

When Sanders told Schumacher about the monster who lived alone in the forest…

“Tom offered the crucial observation that – because the animal world is already alien to us – I should consider relocating the creature to the human world.”

With that in mind, Chris dusted off the story and went to work.

Over the next three months, Sanders created a pitch book for the proposed animated film. What he came up with was very different from the version of Lilo & Stitch that eventually hit theaters in 2002.

The Most Dangerous Creature in the Known Universe

The pitch – first shared with Walt Disney Feature Animation staffers on January 9, 1998 – was titled: Lilo & Stitch: A love story of a girl and what she thinks is a dog.

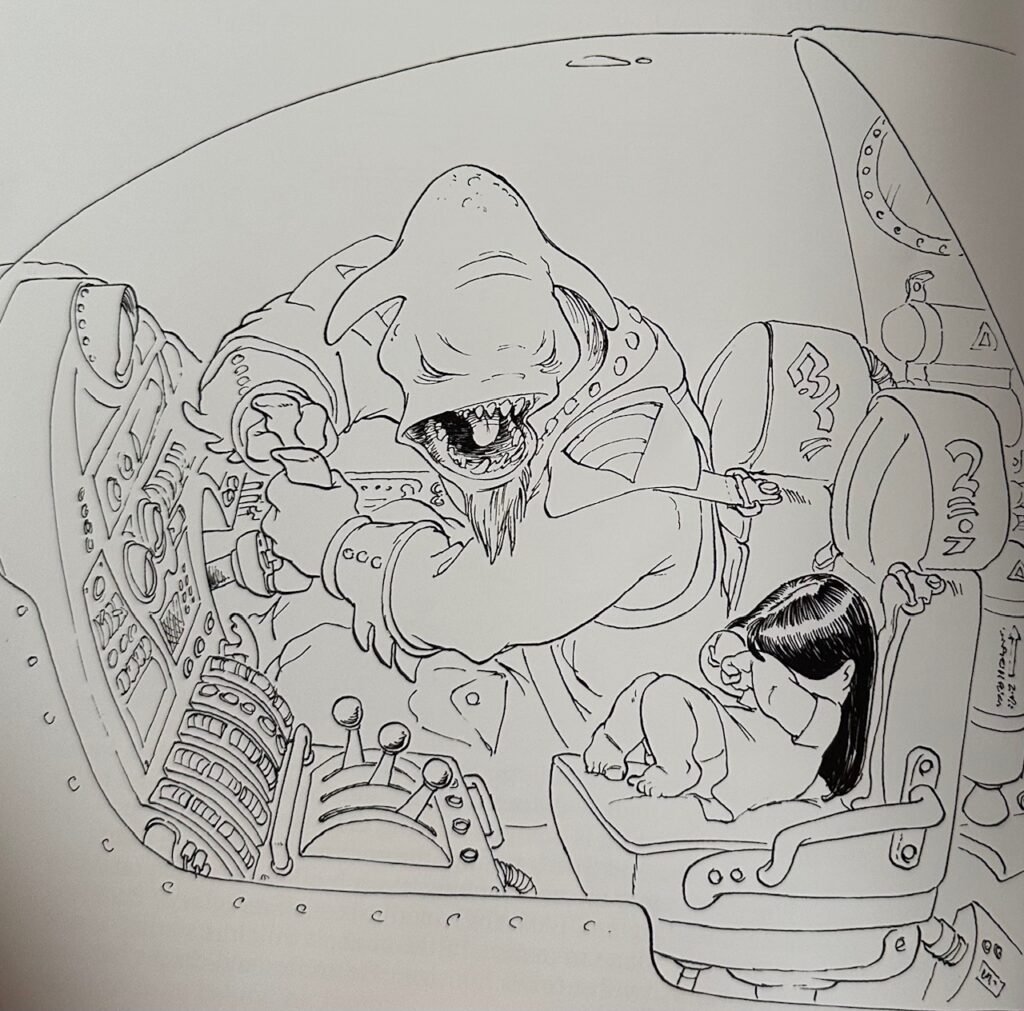

This early version of Stitch was… not cute. Not cuddly. He was mean, selfish, self-centered – a career criminal. When the story opens, Stitch is in a security pod at an intergalactic trial, found guilty of 12,000 counts of hooliganism and attempted planetary enslavement.

Instead of being created by Jumba, Stitch leads a gang of marauders. His second-in-command? Ramthar, a giant, red shark-like brute.

When Stitch refuses to reveal the gang’s location, he’s sentenced to life on a maximum-security asteroid. But en route, his gang attacks the prison convoy. In the chaos, Stitch escapes in a hijacked pod and crash-lands on Earth.

Earth in Danger, Jumba on the Hunt

Terrified of what Stitch could do to our technologically inferior planet, the Grand Council Woman sends bounty hunter Jumba – along with a rule-abiding Cultural Contamination Control agent named Pleakley – to retrieve (or eliminate) Stitch.

Their mission must be secret, follow Earth laws, and – most importantly – ensure no harm comes to any humans.

Naturally, Stitch ignores all that.

After his crash, Stitch claws out of the wreckage, sees the lights of a nearby town, and screams, “I will destroy you all!” That plan is immediately derailed when he’s run over by a convoy of sugar cane trucks.

Waking up in the local humane society, Stitch sees a news report confirming the Federation is already hot on his trail. He needs to blend in. Fast.

Enter Lilo

Lilo is a lonely little girl, mourning her parents, looking for a pet. Stitch plays the role of a “cute little doggie” because it’s a means to an end. At this point, Lilo is just someone to use while he builds a communications device.

Using parts from her toys and a stolen police radio, Stitch contacts his old gang. But Ramthar, now the leader, isn’t thrilled. Still, Stitch sends a signal.

Then he builds an army.

Stitch Goes Full Skynet

Stitch constructs a small robot, sends it to the junkyard to build bigger robots. Soon, he has an army. When Ramthar and crew arrive, Stitch’s robots surround them. Ramthar is furious, but Stitch regains command.

Next, Stitch sets his robotic horde on a nearby town. Everything goes smoothly until a robot targets the hula studio where Lilo is dancing. As it lifts her in its claw, Stitch has a change of heart. He saves her.

From here, the plot begins to resemble the Lilo & Stitch we know today. Sort of.

The Ending That Never Was

In Sanders’ original version, it’s not Captain Gantu who kidnaps Lilo, but Ramthar. And when the Grand Council Woman comes to collect Stitch, Lilo produces a receipt from the humane society.

“I paid a $4 processing fee to adopt him. If you take Stitch, you’re stealing.”

The Grand Council Woman crumples the receipt and says, “I didn’t see it.”

Nani chimes in: “Well, I saw it.”

Then Jumba. Then one of Stitch’s old crew. Then a hula girl. And finally, Pleakley pulls out his CCC badge and says:

“Well, I am Pleakley Grathor, Cultural Contamination Control Agent No. 444. And I saw it.”

Pleakley saves Stitch.

How Roy E. Disney Made Stitch Cuddly

Ultimately, this version of Lilo & Stitch was streamlined. Roy E. Disney believed Stitch shouldn’t be nasty. Just naughty. And not by choice – he was designed that way.

Which is how Stitch became Experiment 626. A misunderstood creation of Jumba the mad scientist, not a hardened criminal with a vendetta.

The rest, as they say, is history.

Ricardo Montalbán’s Lost Role

Here’s a detail that even hardcore Lilo & Stitch fans may not know: Ricardo Montalbán—best known as Mr. Roarke from Fantasy Island and Khan Noonien Singh from Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan—was originally cast as the voice of Ramthar, Stitch’s second-in-command in this early version of the film. He had already recorded a significant amount of dialogue before the story was reworked following Roy E. Disney’s guidance. When Stitch evolved from a ruthless galactic outlaw to a misunderstood genetic experiment, Montalbán’s character (and much of the original gang concept) was written out entirely.

Which is kind of wild when you think about it. Wrath of Khan is widely considered the gold standard of Star Trek films. So yes, for a time, Khan himself was supposed to be part of Disney’s weirdest sci-fi comedy.

Stitch’s Legacy (and Why It Still Resonates)

Looking back at Stitch’s original story, it’s wild to think how close we came to getting a very different kind of movie. One where our favorite blue alien was less “ohana means family” and more “I’ll destroy you all.” But that transformation—from outlaw to outcast to ohana—is exactly what makes Lilo & Stitch so special.

So as the live-action version prepares to hit theaters, keep in mind that behind all the cuddly merch and tiki mugs lies one of Disney’s strangest, boldest, and most hard-won reinventions. One that started with a forest monster and became a beloved franchise about found family.

June 26th is officially Stitch Day—so mark your calendar. It’s a good excuse to celebrate just how far this little blue alien has come.

Film & Movies

How “An American Tail” Led to Disney’s “Hocus Pocus”

Over the last week, I’ve been delving into Witches Run Amok, Shannon Carlin’s oral history of the making of Disney’s Hocus Pocus. This book reveals some fascinating behind-the-scenes stories about the 1993 film that initially bombed at the box office but has since become a cult favorite, even spawning a sequel in 2022 that went on to become the most-watched release in Disney+ history.

But what really caught my eye in this 284-page hardcover wasn’t just the tales of Hocus Pocus’s unlikely rise to fame. Rather, it was the unexpected connections between Hocus Pocus and another beloved film—An American Tail. As it turns out, the two films share a curious origin story, one that begins in the mid-1980s, during the early days of the creative rebirth of Walt Disney Studios under Michael Eisner, Frank Wells, and Jeffrey Katzenberg.

The Birth of An American Tail

Let’s rewind to late 1984/early 1985, a period when Eisner, Wells, and Katzenberg were just getting settled at Disney and were on the hunt for fresh projects that would signal a new era at the studio. During this time, Katzenberg—tasked with revitalizing Disney Feature Animation—began meeting with talent across Hollywood, hoping to find a project that could breathe life into the struggling division.

One such meeting was with a 29-year-old writer and illustrator named David Kirschner. At the time, Kirschner’s biggest credit was illustrating children’s books featuring Muppets and Sesame Street characters, but he had an idea for a new project: a TV special about a mouse emigrating to America, culminating in the mouse’s arrival in New York Harbor on the same day as the dedication of the Statue of Liberty in 1886.

Katzenberg saw the patriotic appeal of the concept but ultimately passed on it, as he was focused on finding full-length feature projects for Disney’s animation department. Kirschner, undeterred, took his pitch elsewhere—to none other than Kathleen Kennedy, Steven Spielberg’s production partner. Kennedy was intrigued and invited Kirschner to Spielberg’s annual Fourth of July party to pitch the idea directly to the famed director.

Spielberg immediately saw the potential in Kirschner’s idea, but instead of a TV special, he envisioned a full-length animated feature film. This project would eventually become An American Tail, a tribute of sorts to Spielberg’s own grandfather, Philip Posner, who emigrated from Russia to the United States in the late 19th century. The film’s lead character, Fievel, was even named after Spielberg’s grandfather, whose Yiddish name was also Fievel.

Disney’s Loss Becomes Universal’s Gain

An American Tail went on to become a major success for Universal Pictures, which hadn’t been involved in an animated feature since the release of Pinocchio in Outer Space in 1965. Meanwhile, over at Disney, Eisner and Wells weren’t exactly thrilled that Katzenberg had let such a promising project slip through his fingers.

Not wanting to miss out on any future opportunities with Kirschner, Katzenberg quickly scheduled another meeting with him to discuss any other ideas he might have. And as fate would have it, Kirschner had just written a short story for Muppet Magazine called Halloween House, about a boy who is magically transformed into a cat by a trio of witches.

The Pitch That Sealed the Deal

Knowing Katzenberg could be a tough sell, Kirschner went all out to impress during his pitch. He requested access to the Disney lot 30 minutes early to set the stage for his presentation. When Katzenberg and the Disney development team walked into the conference room, they were greeted by a table covered in candy corn, a cauldron of dry ice fog, and a broom, mop, and vacuum cleaner suspended from the ceiling as if they were flying—evoking the magical world of Halloween House.

Katzenberg was reportedly unimpressed by the theatrical setup, muttering, “Oy, show-and-tell time” as he took his seat. But Kirschner knew exactly how to grab his attention. He started his pitch with the fact that Halloween was a billion-dollar business—a figure that made Katzenberg sit up and take notice. He listened attentively to Kirschner’s pitch, and by the time the meeting was over, Katzenberg was convinced. Halloween House would become Hocus Pocus, and Disney had its next big Halloween film.

A Bit of Hollywood Drama

Interestingly, Kirschner’s success with Hocus Pocus didn’t sit well with his old collaborators. About a year after the film’s release, Kirschner ran into Kathleen Kennedy at an Amblin holiday party, and she wasted no time in expressing her disappointment. According to Kirschner, Kennedy said, “You really hurt Steven.” When Kirschner asked how, she explained that Spielberg and Kennedy had given him his big break with An American Tail, but when he came up with the idea for his next film, he brought it to Disney rather than to them.

Hollywood can be a place where loyalty is valued—or, at least, perceived loyalty. At the same time, this was happening just as Katzenberg was leaving Disney and partnering with Spielberg and David Geffen to launch DreamWorks SKG, which only added to the tension. Loyalty, as Kirschner found out, can be an abstract concept in the entertainment industry.

A Halloween Favorite is Born

Despite its rocky start at the box office in 1993, Hocus Pocus has gone on to become a beloved part of Halloween pop culture. And, as Carlin’s book details, its success helped pave the way for more Disney Halloween-themed projects in the years that followed.

As for why Hocus Pocus was released in July of 1993 instead of during Halloween? That’s a story for another time, but it has something to do with another Halloween-themed project Disney was working on that year—Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas—and Katzenberg finding himself in the awkward position of having to choose between keeping Bette Midler or Tim Burton happy.

For more behind-the-scenes stories about Hocus Pocus and other Disney films, be sure to check out Witches Run Amok by Shannon Carlin. It’s a fascinating read for any Disney fan!

And if you love hearing these kinds of behind-the-scenes stories about animation and film history, be sure to check out Fine Tooning with Drew Taylor, where Drew and I dive deep into all things movies, animation, and the creative decisions that shape the films we love. You can find us on your favorite podcast platforms or right here on JimHillMedia.com.

-

Film & Movies9 months ago

Film & Movies9 months agoBefore He Was 626: The Surprisingly Dark Origins of Disney’s Stitch

-

History8 months ago

History8 months agoCalifornia Misadventure

-

Film & Movies9 months ago

Film & Movies9 months agoThe Best Disney Animation Film Never Made – “Chanticleer”

-

Television & Shows10 months ago

Television & Shows10 months agoThe Untold Story of Super Soap Weekend at Disney-MGM Studios: How Daytime TV Took Over the Parks

-

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment8 months ago

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment8 months agoThe ExtraTERRORestrial Files

-

History9 months ago

History9 months agoWhy Disney’s Animal Kingdom’s Beastly Kingdom Was Never Built

-

Podcast11 months ago

Podcast11 months agoEpic Universal Podcast – Aztec Dancers, Mariachis, Tequila, and Ceremonial Sacrifices?! (Ep. 45)