Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment

A Chilly Season on the Great White Way

Seth Kubersky returns from a recent trip to the Great White Way and shares his thoughts about two poorly reviewed musicals: “The Boy from Oz” and “Taboo.”

When most people think of holiday time in New York City, they see images of warmth and nostalgia. The majestic balloons of the Macy’s parade, the glowing tree at Rockefeller Center, warm chestnuts from a street cart vendor. But the first thing I think of is the cold. Bitter, bone-breaking cold. Six years of living in Florida has thinned my blood to the point that a week-long visit with the family feels like six months in the arctic. The electronic time-and-temperature hovering over Times Square may read 40 degrees, but when the wind whips down the canyons of Broadway, it feels like less than half of that.

But as cold as this Thanksgiving might have been for me, it’s been even colder for producers of Broadway shows. This fall season has been the most brutal in recent memory for new productions. Ellen Burstyn’s “Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All” closed 24 hours after opening. “Six Dance Lessons in Six Weeks” and “Jackie Mason: Laughing Room Only” had similarly short runs, and “Bobbi Boland” didn’t even make it to opening night. The verdict is still out on the long-term prospects for “Wicked”, a revisionist prequel to the Wizard of Oz. The only genuine hit this year with both critics and audiences has been “Avenue Q”, the brilliant Sesame Street satire that transferred from Off-Broadway last spring. A visit to TKTS, the discount booth that sells unsold tickets at half price, tells the story: nearly every show, save a few long-running hits like “The Lion King” and “The Producers”, had tickets available during what is normally a busy holiday weekend.

In the middle of all this, two strikingly similar shows opened. The markedly different reactions to these two shows, both by the press and at the box office, illustrates how conventional wisdom, rather than talent or quality, is what ultimately makes or breaks a show in New York. Both are biographical musicals, told in flashback, about the life of a gay pop musician in the 1980’s. Both feature musical scores written by the subject, and feature name-brand stars in a leading role. Both have received less than glowing reviews from the New York critics. But one is regarded as a relative success in this dismal Broadway season, with decent word-of-mouth and healthy box office. The other is being openly derided in both the critical and popular press as a spectacular flop, and its name is quickly becoming synonymous with “epic disaster”. One is an amusing trifle that is pleasant enough, but quickly fades from the mind, while the other is ambitious, moving, and genuinely deserving of a life beyond its current incarnation. And you might be very surprised to learn which is which.

The first show is “The Boy from Oz”, the story of Peter Allen as portrayed by Hugh Jackman. At the risk of committing musical-theater heresy, I didn’t know Peter Allen from Peter Parker before seeing the show. It turns out Allen was a singer-performer from Australia (the “Oz” of the title) who played an opening act for Judy Garland, married her daughter Liza Minnelli, had a successful nightclub act, and wrote a number of award-winning songs. He was also gay (apparently a common theme among Liza’s husbands) and died of AIDS in 1992.

The story is narrated by Allen, looking back over his life. Amusing vignettes from his experiences in show biz alternate with his songs, which are shoehorned into the plot with limited success. I only recognized a handful of the numbers, namely “The Theme from Arthur” and “Don’t Cry Out Loud”, and found most of the songs inoffensive but unmemorable. Worse, they violate the cardinal rule of musical theater, in that they express things that have already been stated, and don’t advance the plot in any meaningful way. The supporting cast is fine, particularly Isabella Keating and Stephanie J. Block, who contribute eerie wax-museum impressions of Garland and Minnelli. Jarrod Emick is also memorable in his brief second-act roll as Allen’s boyfriend. The only true standout supporting player is the young Mitchel David Federan, who steals the show with an opening number song-and-dance routine as a pre-teen Allen. Even the sets, costumes, and choreography, while competent, are underwhelmingly minimal for such a larger-than-life story.

What saves this show from disaster is Hugh Jackman’s performance as Peter Allen. American fans who know him from his blockbuster movies might wonder if he can really sing and dance, much less play piano with those adamantium claws protruding from his knuckles. The answer, as anyone who saw his performance in London’s “Oklahoma!” (recently televised on PBS) can testify, is “yes, and how!” Jackman is charming and engaging from the opening moments, with a powerful singing voice and polished dance moves. Most importantly, he has the stage presence and charisma to sustain an audience’s attention through what is a fairly thin story. Unlike many movie stars who perform on Broadway, Jackman shows astounding endurance, staying on stage nearly every minute of the play. He also seems remarkably un-self-conscious about his macho screen image, capturing Allen’s flamboyant mannerisms with flair and flirting equally with male and female audience members.

Ultimately, while the show survives on Jackman’s charms, it lacks in depth or complexity. Aside from an 11th-hour revelation of childhood trauma, there is little shown of Allen’s psychological reality. It’s hard to tell if he kept his dark side remarkably well hidden, or if there simply wasn’t anything more to him than his stage persona. Jackman receives well-deserved standing ovations for the energy and likeability of his performance, but I walked out knowing nothing about the real Peter Allen that I couldn’t have learned from a 1-paragraph bio. The show is worth seeing (but not a full price) for Jackman alone, but I can’t see it having any staying power once he goes back to Hollywood.

“Taboo” is in many ways the mirror-universe dark twin of “The Boy from Oz”. Like “Oz”, it charts the life of a gay pop-music icon. In both, the first act chronicles his rise from obscurity to the first tastes of success, while in the second he succumbs to the excesses of fame. In both, there is an untimely death from AIDS, followed by an uplifting finale of hope and redemption through art.

The subject of “Taboo” is George O’Dowd, better known as Boy George, lead singer of the 80’s pop group Culture Club. His story is narrated in flashback by Philip Salon, a nightclub impresario who claims to have discovered Boy George. Salon’s account is constantly challenged by a second narrator, Big Sue, making for a hilarious exploration of the flexible nature of memory. We see George’s rise from coat checker to pop star, and his subsequent public descent into heroin addiction. Running parallel to George’s story is that of Leigh Bowery, an outrageous performance artist and designer played by the real George O’Dowd. This bit of casting, coupled with lead actor Euan Morton’s striking resemblance to the young Boy George, leads to such surreal delights as O’Dowd telling his younger self that “Karma Chameleon” is a terrible song that will never go anywhere.

The cast of “Taboo” is nearly uniformly excellent. Euan Morton not only looks like the 80’s-era Boy George, but sings like him too. He gives the performance an unexpected depth and vulnerability under the makeup. Even better is Raul Esparza as Salon. Raul’s theatricality and vocal contortions make him a love-it-or-hate-it performer, and I fall squarely in the love-it camp. He brings the same blend of sinister mystery and raw power that made him the best Riff Raff since Richard O’Brien created the role in “The Rocky Horror Show”. Here, he nearly steals every scene he’s in, only to be undercut by the earthy and profane Big Sue. As portrayed at the performance I saw by understudy Brooke Elliott, Sue is the most human character, a cynical romantic, with a stunning solo number in the second act. Surprisingly, the weakest link performance-wise is O’Dowd himself. He is heavy, stiff, and his voice is a croaking shadow of its former self, particularly in the first act. He seems mainly to exist in the show to display one astounding costume design after another.

But if George O’Dowd the actor is a disappointment, George O’Dowd the composer is a revelation. Though I grew up in the 80’s, I largely ignored the pop music of the time. While my peers were obsessing over Michael Jackson and Madonna, my Walkman was playing the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. I could probably hum a few bars of “Karma Chameleon” and “Do You Really Want to Hurt Me”, but I was never a fan of Culture Club. While both those songs are briefly heard in “Taboo”, along with an excerpt from “Church of the Poison Mind”, they are the exception. The rest of the score consists of hauntingly beautiful ballads and rocking techno-flavored dance numbers. The scores for “Urinetown” and “Avenue Q” are wittier, but “Taboo” has the most moving and memorable new melodies of any recent Broadway show. The nearest shows one can compare it to in style are “Aida” and “Rent”, and this blows both of those over-rated scores out of the water. If “Taboo” fails before a cast album is recorded, it would be a great tragedy, because these performances and this music need to be preserved.

“Taboo” is not without its flaws. While the music is consistently wonderful, the book is less so. Charles Busch, author of “Vampire Lesbians of Sodom”, has written some beautifully bitchy dialogue, but the structure is uneven, and the tone becomes abruptly dark in the second act. The show’s biggest flaw, as pointed out by all the critics, is that Boy George’s story never intersects with Leigh Bowery’s. As a result, you have two separate plots that alternate, with only a few characters that cross over between them. This wouldn’t be a problem if the stories commented on each other in a thematically meaningful way, but the connection never really becomes clear. In truth, this isn’t a fatal flaw, though the way critics have harped on it would make you think it ruins the show. Other elements that have been derided critically, such as the choreography, the over-the-top costume designs, and a video tribute to the real-life Bowery, I found to be assets to the show.

So why has the lesser of these two shows received a free pass from the press, and is in the top-5 for ticket sales, while the other is openly mocked and struggling financially? I must admit that the reviews led me to “Taboo” with a gleeful sense of schadenfreude. I never had the chance to see “Carrie” or “Legs Diamond”, so I figured this was my chance to be able to tell my children I saw one of the biggest train wrecks in Broadway history. Imagine my surprise when I turned to my seat-mate at intermission and said, “You know, this is pretty damn good”. If you had told me when I walked in that I’d be giving a standing ovation at the curtain, I’d never have believed you, but there I was.

What could make a show that is clearly so much better than many of the successes on Broadway such a pariah among the press?

Much of the blame can probably be laid at the feet of its producer, Rosie O’Donnell. This is a woman badly in need of new publicist. Ever since the cancellation of her TV show, and especially with her highly-publicized lawsuit against her former magazine partner, she’s been on a path of self-destruction. Giving the middle finger to critics in the audience at a recent performance didn’t help her any either. But Rosie is far from the first prickly producer, though being a household name and a woman makes her a more inviting target than most.

Also damaging was the widely-discussed revisions to the show during rehearsals and previews, and a near-mutiny by some cast members. But the truth is that many shows go through growing pains like these, and come out stronger for it. A responsible reviewer should evaluate the final product, and not simply regurgitate tabloid gossip.

Perhaps there is a darker and more disturbing reason for the abuse this show has suffered. American culture as a whole has become much more accepting of gay people and gay culture, and no city is more gay-friendly than New York. You can’t turn on the TV without seeing “Will & Grace” or “*** Eye for the Straight Guy”, and the trend has been discussed endlessly in the press. But the gays that the mainstream accepts are largely safe and neutered. The fashion and attitude associated with homosexuality might be embraced by the larger culture, but the sexuality and politics are not.

This might be the essential difference between the superficially similar “Boy from Oz” and “Taboo”. While the former is informed by the safe camp that appealed to Peter Allen’s straight female audience, the latter embraces the anarchic punk culture that thrived in the underground club scene of Boy George’s London. Or, to use the semiotics of modern activism, Peter Allen was “gay”, but Boy George was “***”.

This essential difference, both in the subjects and their shows, may help explain why the lesser show will probably outlast the better one. After all, New York is the capital of capitalism, and you can’t stay open on Broadway unless you can sell tickets to the blue-hair tourists. It’s just as shame that the press can’t stop bashing “Taboo”, and instead help those tourists look past the unconventional exterior to see the beauty at its heart.

History

California Misadventure

This article is an adaptation of an original Jim Hill Media Five Part Series “California Misadventure” (2000).

Walt Disney was desperate.

Here it was, early 1955. Walt had pumped every penny he had into building “The Happiest Place on Earth” out amongst the orange groves of Anaheim. When he suddenly realized: “There’s no place for them to stay.”

Who’s “them?” Disneyland’s customers. AKA the guests.

All those people who are going to drive up from San Diego, or down from San Francisco. They’d be tired after a full day of touring his “Magic Kingdom.” Disney knew that these folks would want a nice, clean place nearby where they can stay.

But Walt didn’t have the dough necessary to build a hotel next to Disneyland. He barely had enough cash to finish the park itself, let alone build lodgings nearby. But Walt knew that having a nice hotel right next to the park would play a crucial part in the project’s success.

But what could he do? Roy certainly wouldn’t give him the money. ABC was completely tapped out. And Walt had already cashed in his life insurance.

Jack Wrather Helping Disneyland

In desperation, Walt turned to an old friend: television producer Jack Wrather. Jack was someone Walt had been friendly with for years. They were both old pros when it came to surviving in the cut-throat world of the movie business.

These days, though, Jack was definitely on a hot streak. Having produced two of TV’s earliest syndicated hits (“Lassie” and “The Lone Ranger”), Wrather was flush with cash. He had also invested wisely in real estate around Southern California — ending up with big holdings in oil and natural gas.

Using the excuse that he wanted to pick Wrather’s brain concerning his Disneyland project, Walt asked Jack to join him out in Anaheim for a tour of the construction site. It was only after Wrather got there that Jack finally realized that Disney didn’t want to pick his brain. Walt was out to pick his pocket. There among the construction footings, Walt told Jack the story of Disneyland. How he dreamed of building a different kind of family fun park. How he’d need a clean new hotel nearby for visitors to stay in.

Jack listened. Nodded. Smiled. Then said “No.”

Walt persisted. Jack resisted. I mean, to Wrather, Disney’s idea made absolutely no sense. A 17-million-dollar amusement park, built out in the middle of the citrus groves on Anaheim? Who the hell was going to drive out from LA to visit this place, anyway? Walt didn’t need a hotel. He needed his head examined.

But Walt wouldn’t give up. He kept trying to sweeten the deal, first offering Wrather a 99-year lease on the property. Then Walt threw in the Disney name, saying that Wrather could use it on any other hotels he built in Southern California.

At this point, Walt was near tears. Embarrassed at the sight of the weepy movie mogul, Jack finally caved in and agreed to help his friend. But he wasn’t going to build a hotel next to Disneyland. That would just be too expensive. Walt would just have to settle for a motel. And a small one at that.

Disneyland Motel Turns Into the Disneyland Hotel

Of course, everyone knows that Disneyland opened on July 17, 1955. After a somewhat shaky first summer, the park proved to be a hit with the public. On October 5th of that same year, the Disneyland Motel opened on a 60-acre site right across the street from the park. It too would prove to be very popular with the public.

Walt is thrilled with the success of Disneyland. But no more than Jack Wrather was with the success of his Disneyland Motel, which he rapidly turned into a resort-style hotel. Three huge high-rise towers — the Bonita, Sierra and Marina — were quickly thrown up, bringing the total number of rooms on property to over 1,100. Wrather also added several spectacular swimming pools as well as a convention center to the complex.

Walt never forgot Jack’s generosity when it came to building the Disneyland Hotel. When few in Hollywood had any faith at all in Disney’s theme park project, Wrather (albeit somewhat reluctantly) agreed to help his friend. This gesture had meant the world to Walt, so he was constantly looking for ways to repay Wrather for his kindness.

Monorail to the Disneyland Hotel

Take, for instance, the Monorail. When the Disneyland-Alweg monorail system was first installed at the park in 1959, it just took guests on a quick trip around Tomorrowland. But that wasn’t good enough for Walt. He wanted his new train to actually go somewhere and provide a real service.

So, in 1961, Walt decided to extend the monorail’s route. He had a track installed that took the trains out of the park and ran them across the street over to the Disneyland Hotel. Here, passengers could disembark to do some shopping and dining at the resort. Or they could just sit tight in their seat for the return trip to Tomorrowland.

Walt spent millions building the track to get the monorail over to Wrather’s property. Mind you, he never asked Jack to help shoulder the cost. All Disney did was charge the Wrather Corporation a nominal fee to help maintain the hotel’s monorail station.

This one generous gesture added immeasurably to the allure of the Disneyland Hotel. While there may have been other hotels in Anaheim that were more luxurious and better laid out, none of them were directly linked to Disneyland via a state-of-the-art transportation system. It was this distinction that led to the Disneyland Hotel having the highest occupancy rate in all of Orange County.

In his lifetime, Walt always made sure that Jack Wrather and the Wrather Corporation were well taken care of by Walt Disney Productions. It was only after Walt’s death in December 1966 that the coziness between the two companies began to curdle.

Wrather Corporation & Walt Disney Productions

The key sticking point was that deal Disney had worked out with Jack Wrather way back in 1955. By giving the Wrather Corporation a 99 year lease on the Disneyland Hotel site as well as the exclusive right to use the Disney name on any hotels built in Southern California, Walt had effectively cut his own company off from a huge revenue stream ’til 2054.

Think about it: All those hotels in Anaheim, making millions of dollars each year off guests who have come to see Disneyland. And the Mouse doesn’t get a nickel of it — all because of some desperate deal Walt cut with Jack Wrather while weeping in the Disneyland construction site.

Mind you, it’s not like the Mouse didn’t try. Each year, Disney representatives would contact Jack Wrather, saying that they wished to discuss terms for buying out his Disneyland Hotel contract. Each year, Jack would just laugh and say “Thanks but no thanks. I’m happy with the arrangement as is.”

This continued right up until June 1984, when Disney Chairman Ray Watson personally approached Jack about buying back the Wrather Corporation’s Disneyland Hotel holdings. Wrather — whose health was fading at the time — hinted at this particular meeting that he might finally now be ready to sell his property back to the Mouse. But before negotiations could officially get underway, Wrather died in November 1984.

Michael Eisner Making Moves

By then, Michael Eisner and his new management team had already taken up residence at Walt Disney Productions. One of Eisner’s first goals was to radically improve the company’s bottom line, which meant he had to quickly increase the amount of money the company’s theme parks generated.

To do this in Florida, Eisner just okayed construction of two huge new hotels at the WDW resort: The 900 room Grand Floridian and the 2,100 room Caribbean Beach Resort. Eisner had planned to do the same thing at Disneyland — only to discover that A) the Disney Company didn’t own any hotels in Anaheim, B) they didn’t have sufficient land to build any new resorts, anyway, and C) only the Wrather Company had the rights to use the Disney name on hotels built in Southern California.

Eisner was dumbfounded when he heard about this. He turned to his newly hired Disney Chief Financial Officer Gary Wilson and said: “Handle this. I don’t care how you do it, but I want that contract broken. The Walt Disney Company has to be the sole owner and operator of the Disneyland Hotel.”

Wilson met with Watson and learned that Wrather had really almost been ready to sell Disney back the Disneyland Hotel when he passed away in November. In the meantime, Wilson gathered intelligence about the Wrather Corporation. He learned that — since Jack’s death — the company had fallen on extremely hard times. To keep afloat financially, the Wrather Corporation had already sold off several premium assets: Its oil and natural gas holdings, as well as the syndication rights to “The Lone Ranger ” and “Lassie.”

Wrather Corporation Under Attack

It seemed like this financial crisis might be the ideal time to approach Wrather with an offer to buy up the Disneyland Hotel acreage and contract. And Wilson was just getting to do this, when word came from Wall Street that a New Zealand-based firm — Industrial Equity — had bought up 28% of the Wrather Corporation.

This firm — run by corporate raider Ronald Brierley — quickly made its intentions known: It filed reports with the Securities and Exchange Commission that it intended to buy up at least half of Wrather Corporation.

Sensing that Disney’s opportunity to gain control of the hotel was slipping away, Wilson and his team moved quickly. They immediately asked for a meeting with Wrather Corporation management. While in that meeting, Wilson voiced Disney’s disapproval that the ownership of the Disneyland Hotel could slip away to a foreign green-mailer like Brierley.

While Disney officially could do nothing to derail Wrather’s deal with Industrial Equity, Wilson did point out that the hotel’s monorail maintenance contract was soon up for renegotiation. Wilson then told Wrather management that the Mouse was considering a slight hike in the monorail maintenance fee. Like to — say — $10,000 a day?

Disney’s threat was none so subtle, but very clear. Should Wrather try to sell off their Disneyland Hotel holdings to anybody but the Mouse, Disney would make operating the monorail so prohibitively expensive for the new owners that there was no way that they could ever make money off the hotel. Faced with these terms, Wrather had no choice but to begin serious sale talks with the Mouse.

Unfortunately, the Disneyland Hotel sale negotiations dragged on for months. Disney felt that Wrather was asking too high a price for the property, while Wrather’s people thought that the Mouse’s offers were embarrassingly low. With no resolution in sight, the sales talks plodded on into 1987, eventually rolling into 1988.

Walt Disney Company Gains Control of the Disneyland Hotel

Desperate to finally get its hands on the Disneyland Hotel, the Mouse did the unthinkable: It actually got in bed with Ronald Brierley and Industrial Equity. Together, the two companies bought up the remaining 78% of Wrather Corporation for $109 million. Each firm got 50% of the Wrather Company. But only the Mouse got the rights to run the Disneyland hotel as well as develop the surrounding Anaheim property.

Six months later, the Mouse turned around and bought out Industrial Equity’s portion of the Wrather Corporation. This took over $85 million, which Brierley gleefully pocketed before heading back to New Zealand.

So, in January 1989 — after 34 years and a total of $161 million dollars — the Mouse had finally regained control of the Disneyland Hotel. Given that Wrather Corporate has allowed the hotel’s 1,100-plus rooms to fall into disrepair, the first order of business was a $35 million rehab of the entire resort.

But the big news is the Walt Disney Company had finally regained control of its own name. Now it could launch a whole series of Southern California hotels if it chose to …

Only Michael didn’t choose to. He realizes that Disneyland — as it is currently configured — is strictly a one-day park. Guests would typically arrive in Anaheim that morning to see the park and its new attractions, then drive back home that night.

Consequently, there was no point in doing a Walt Disney World-style ramp-up of the number of Disney-owned hotel rooms at the Disneyland resort.

Unless…

Unless there was a reason for all those people to now stay two days in Anaheim. Like — say — a brand new Disney theme park in Southern California for them to see?

Intrigued by this idea, Eisner calls in the Imagineers. He outlines his idea of building a second Disney theme park in Southern California. He sends them back to WDI, telling them to return in one month’s time with plans for new Disney theme parks. His one creative directive: “Amaze me. Astound me.”

When the Imagineers finally do return one month later to show Eisner their proposals for new Southern Californian theme parks, they did actually amaze their new boss.

They’d proposed building two distinctly different Disney theme parks in two unlikely locations — one in Disneyland’s old parking lot, the other along the waterfront in Long Beach.

Long Beach vs. Anaheim

The rumors began flying in March 1990.

The Mouse was up to something.

Something big.

For months now, Disney had been meeting privately with the port authorities and city officials of Long Beach. Everyone the Mouse spoke with was sworn to secrecy. But — even so — little tidbits had begun to leak out about this highly hush-hush project.

Like … whatever Disney was up to, the company would be spending at least a billion dollars to get the thing up out of the ground. And … The project would feature a massive port for cruise ships, as well as several seaside luxury hotels. Best of all, there was talk of an elaborate new Disney theme park.

Long Beach residents were thrilled by these rumors.

The people of Anaheim, as you might understand, were not.

For years now, Orange County residents had listened politely as Disneyland cast members complained about how the company’s pre-existing deal with the Wrather Corporation prevented the Mouse from expanding in Anaheim. Well, that contract was null and void now. So where was Disney? Not planning any projects for Orange County, that’s for sure. The Mouse is down by the water, mapping out mega-resorts with his new pals from Long Beach.

Anaheim officials felt hurt and betrayed by what they perceived as the Mouse turning his back on his long-time friends. But — rather than get mad — these Orange County officials became determined to win back Disney’s affections. They’d do whatever they had to get back in Mickey’s good graces.

Which is exactly what the Mouse had hoped they’d do.

Ah — if we’d only known for sure what the Disney Company was actually up to, way back then in 1990-1991. We could have gotten a big box of popcorn and sat right down front. ‘Cause this was “Show Business” on a grand scale, with the real emphasis on “Business.”

As in “Giving Someone the Business.”

I mean, this was manipulation on a masterful, massive scale. The Walt Disney Company successfully pitting two major Southern Californian cities against one another, with Anaheim and Long Beach battling to see who would have the privilege of paying a billion dollars for public improvements (stuff like new highway ramps, street widening, etc.) that Disney insisted were necessary to properly launch its new theme park. All that time, all that energy, all the money expended, just so that city can have the bragging rights to having bagged the new Disney kiddie park? It hardly seems worth the effort.

Is the Mouse really that Machiavellian? Let’s look at the time line, kiddies.

Westcot & Disney Seas

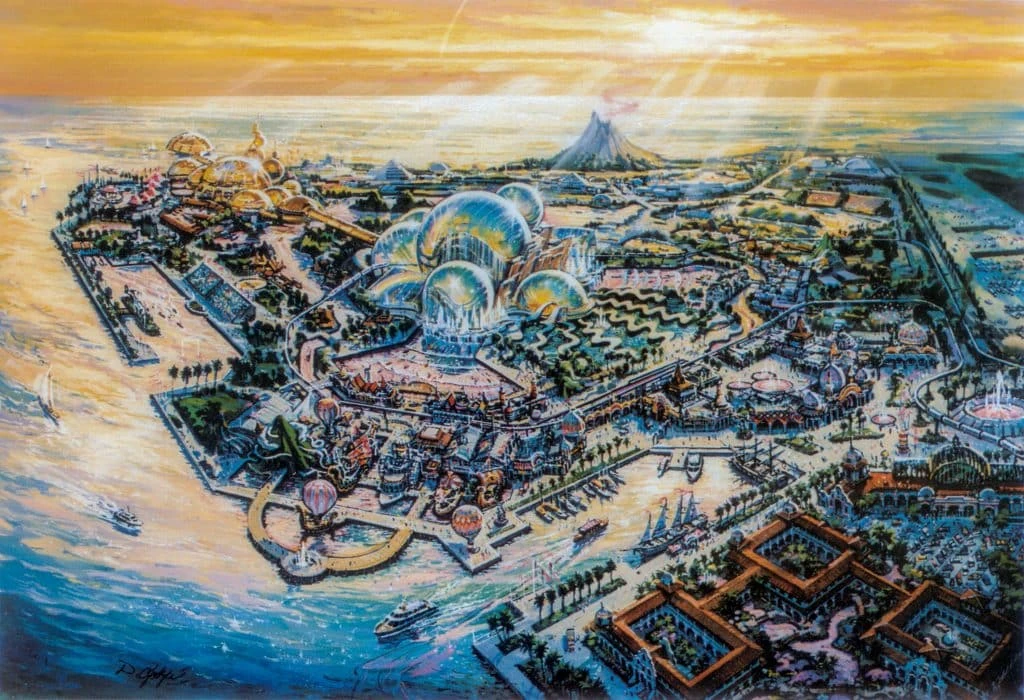

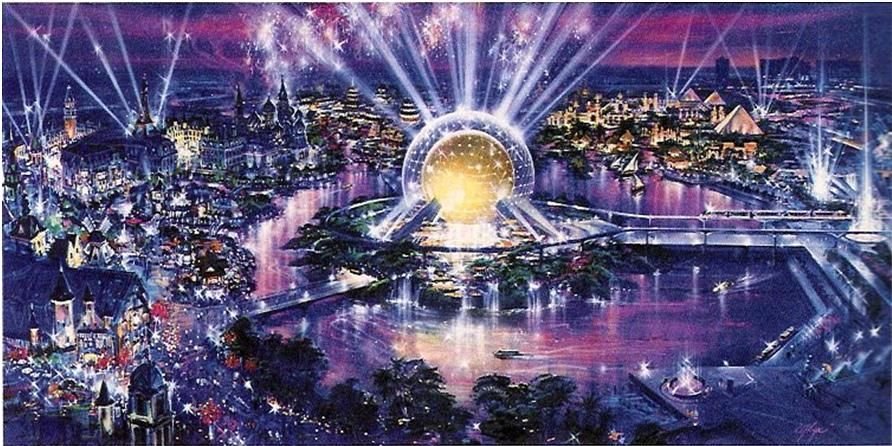

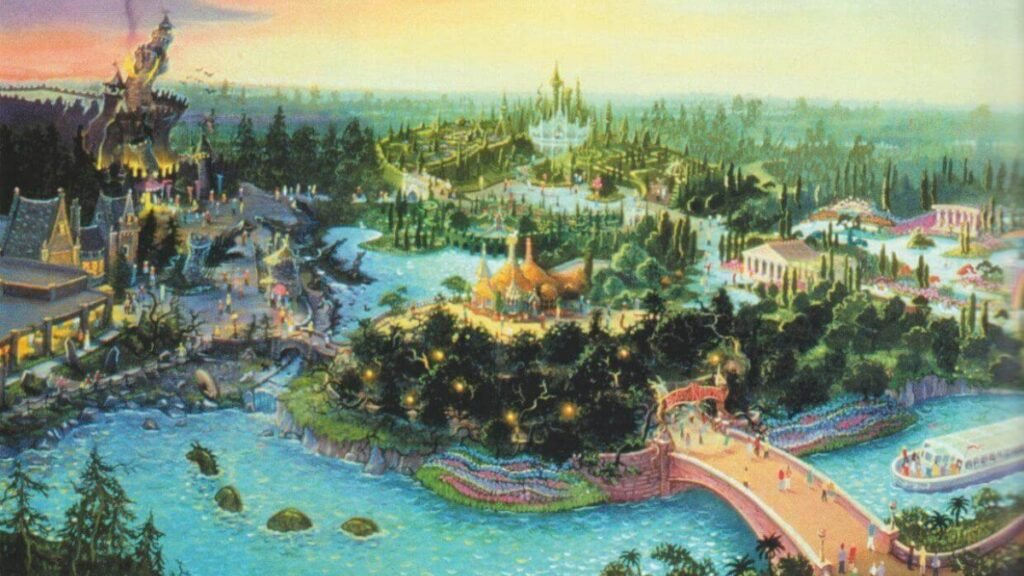

January 1989: Michael Eisner asks the Imagineers to come up with some ideas for new Disney attractions for Southern California. WDI delivers two killer concepts to its CEO: Westcot Center and Disney Seas.

Truth be told, there are some obvious similarities between the two proposed theme parks. Westcot Center and Disney Seas both had bold designs that depart radically from the look and feel of classic Disneyland. Mind you, the two proposed parks aren’t that original. Both used a giant knock-off of Epcot Center’s Spaceship Earth as their centerpiece / icon (Westcot Center has its great golden Spacestation Earth, while the Disney Seas park has its bright blue Oceana.)

Most importantly, both Westcot Center and Disney Seas are going to be almost prohibitively costly to construct. Initial estimates suggest that the parks will each cost $3 billion to build.

That’s a lot of money for the Walt Disney Company to have to lay out all on its own; particularly in 1989, when the Mouse is still recovering from the massive construction bills the company ran up hurrying to finish Walt Disney World’s (WDW) Disney-MGM Studio theme park in Orlando in time for its grand opening in May of that year.

And then there’s the cash the Mouse has to have on hand to cover the costs of its portion of the Euro Disney. (This was way back when Disney thought that Euro Disney was going to be a guaranteed goldmine. Which just goes to show that the Mouse doesn’t always know what it’s doing. Anyhow… )

Disney needed a way to make either of these projects more financially viable (read that as “cheaper to build”). The easiest way to do this was to persuade an outside party to take on a portion of the cost. Someone with deep pockets. Like — say — Long Beach, or Anaheim, or even the State of California.

Fighting for the Mouse

Disney worked hard to keep all the outside parties involved in this project off-center and out of the loop. For example, the Mouse officially announced the “Port Disney” project in April 1990. However, within just a week’s time, the Mouse put out a press release that — in a nutshell – said: “By the way, if we don’t get that modification to the State Coastal Act that we’re looking for, we’re pulling the plug on the whole damned project tomorrow.”

Long Beach — which was desperate to land this $3 billion project (with the hope that it might revitalize its depressed downtown area ) — repeatedly jumped through whatever hoop the Mouse set up. High-ranking city officials even put pressure on Peter Douglas, executive director of the Coastal Commission (reportedly even threatening to have him removed from his $70,000-a-year job), just because he dared to speak out against the “Port Disney” project.

Meanwhile, Anaheim officials continued to pester Disney management, hoping to get it to change its minds about Long Beach and refocus its expansion efforts on Orange County.

One enterprising politician even used Disneyland’s July 17th birthday celebration as a forum to plead the county’s case. Standing on stage in the Magic Kingdom, he departed from his scripted birthday greeting to personally urge Michael Eisner to bring the California second gate project back to Anaheim. Michael was not amused.

Little did this politician realize that the other shoe was about to drop. Disney was continually finding its efforts to clear all the legal hurdles to build Disney Seas / Port Disney stymied by environmentalists. Three of California’s largest environmental groups had banded together to protest the project. They had a particular problem with the Mouse’s plan to fill in 256 acres of San Pedro Bay so it could build its Disney Seas theme park.

Sensing that “Disney Seas” might end up going the way of the Titanic, the Mouse unofficially put the word out during the summer of 1990 that it might have another Californian theme park in the works, just in case “Port Disney” fell through.

Orange County officials were further heartened in February 1991, when they learned that the Disney Company had purchased 23 acres of land in Anaheim. Why would you buy land if you didn’t intend to build something on it?

Still, the Mouse worked hard at keeping Anaheim officials off-balance. It would leak detail about the proposed Anaheim second gate, then have a ribbon cutting for the “Port Disney” visitor center the very next day.

By May 1991, when Disney finally officially unveiled its $3.1 billion plan for the Westcot / Disneyland Resort project, the Anaheim city fathers were complete basket cases. While they were thrilled that Disney had finally revealed its plans for a second Anaheim park, they were also terrified that the project might suddenly fall through.

The Mouse had these guys right where it wanted them, particularly when it began issuing statements such as (when asked in a straightforwardly fashion) whether the company intended to build just Westcot or just Disney Seas, a Mouse-ka-spokesman replied: “While it wants to build both, the Walt Disney Company can only build one of these parks in the 1990s. The company will build first in the city that provides us with the best support package.”

The Mouse’s message was clear: Give us what we want (In Anaheim, Disney was looking for $1 billion worth of street widening, tree planting and public improvements. At Long Beach, Disney was asking for $880 million worth of highway improvements) or we’ll go with the other guy.

In the end, Anaheim did exactly what Disney asked. They even tabled discussion of a theme park admission tax because the Mouse threatened to cancel Westcot if the proposed tax ever came up for a vote.

By the fall of 1991, though Disney would never publicly admit to it, the company had given up on its Long Beach project. The state of California had refused to give the Mouse the zoning variance it needed to fill in that portion of San Pedro Bay. Without that additional land to build on, the whole “Port Disney” project was no longer viable.

Just days before Christmas, Long Beach got a huge lump of coal in its stocking, as Disney officially cancelled the “Port Disney” project. Had the project actually gone forward, “Disney Seas” would have created 20,000 jobs for the community.

Orange County officials rejoiced at this news, little realizing how often they’d been manipulated by the Mouse during the selection process.

And the manipulation would continue for months to come — as the Disney Company would repeatedly seek Anaheim’s approval for the numerous changes it would make to Westcot’s master plan.

Would Westcot Have Been Better Than Disney California Adventure?

Why do Disneyana buffs constantly complain about Disney’s California Adventure?

It’s not so much about what DCA is, as it is about what that park isn’t.

Imagine if there was an announcement in your local paper that a major company intended to build a world class restaurant, right in your home town. Their plans called for the restaurant to be housed in an elegant building surrounded by beautiful gardens. Inside, they’d serve delicious food while live bands performed.

Wouldn’t you be excited if you heard that a place like that was coming to your town?

Conversely, wouldn’t you be disappointed if you were to learn that — after years of hype — the same company had decided not to construct the elegant restaurant, but were opting instead to build a McDonalds on that site?

One might argue that a restaurant is a restaurant. Food is food. It doesn’t much matter if an elegant restaurant is replaced by a fast food place. You still have somewhere to eat.

This is why Disneyana buffs are so upset. In their minds, they were promised the beautiful restaurant (Westcot) but ended up with McDonald’s (DCA).

It doesn’t much matter that many of the very same Imagineers who dreamed up Westcot also worked on attractions for DCA. Not to the Disney die-hards, anyway. All that they remember — all too keenly — are the plans for Westcot. Next to the greatness-that-might-have-been of that grandiose resort, everything — particularly California Adventure — pales in comparison.

Was this abandoned-but-not-forgotten project worth all this fuss? In a way, yes. Had Westcot been built following the project’s original plan, it would have been the culmination of Disney’s theme park experience. Everything that the Mouse had learned while building resorts in Florida, France and Japan was going to be used back in California.

And how fitting that Disney was going to re-invent the theme park experience — right back in the place where theme parks had been invented in 1955.

Westcot and the original Disneyland Resort plan was truly groundbreaking stuff. It sought to turn Disneyland and the tired collection of motels and fast food joints that surrounded the park as something extraordinary: a lushly gardened, brightly lit urban entertainment center. Had this project gone forward as originally planned, Anaheim could have emerged as one of California’s premier destination resorts.

Journey Through Westcot

You want to know what all the fuss was about? Do you long for a taste of the wonders of Westcot? Here, let me take you on a journey to the greatest theme park the Disney Company never built:

Your day at Westcot begins as you zoom off Interstate 5, driving straight in to one of two massive parking garages that border the reconfigured Disneyland Resort. After parking your car, you hop aboard an elevated shuttle (modeled after the automated system that Orlando International Airport uses to shuttle passengers to its outermost air terminals) which takes you quickly and quietly to Disneyland Plaza.

Though it’s only a short trip to the plaza, you still use this opportunity to eyeball the plush new resort. Off in the distance, you spy the Magic Kingdom Hotel — one of three new resorts the Walt Disney Company has built outside the parks. Its red tile roof and stucco stylings remind you a lot of the historic Spanish missions up in Santa Barbara.

The shuttle’s elevated track also takes you past Disneyland Center — a retail, dining and entertainment area located next to a six acre lake. You notice that many of the buildings in this part of the resort are modeled after memorable Californian landmarks: Catalina’s Avalon Ballroom, Venice Beach’s Boardwalk as well as San Diego’s Coronado Hotel. You make a note to do a little poking around here after your day at Westcot.

But now it’s time to disembark. As you stroll down the steps into Disneyland Plaza, you can’t help but think: this used to be the parking lot? Now it’s a tree-lined, fountain-filled open space, which allows guests a moment or so to get themselves oriented before beginning that day’s adventure.

To your left is Disneyland “Classic.” To your right is Westcot, a stylish rethinking of WDW’s Epcot Center. Everything that makes that Florida theme park fun is recreated here. Everything else that made Epcot somewhat creepy and a bit of a bore has been left behind.

As you push through the turnstile to enter Westcot, the first thing you see is the park’s icon, Spacestation Earth. A giant 300-foot-tall golden ball reminiscent of Epcot’s Spaceship Earth. Even in the distance, it towers over everything. Sitting on a lush green island at the center of World Showcase lagoon, Spacestation Earth is home to the Ventureport.

You’ll have to cross a pedestrian bridge out over the water to reach Spacestation Earth and the Ventureport. But here, you’ll get your first taste of the Wonders of Westcot. Many of your old favorites from Epcot’s Future World — the “Journey into Imagination” ride with Figment and Dreamfinder, the “Body Wars” ride from the”Wonders of Life” pavilion as well as the “Horizons” ride — will be waiting for you here, where you can “Dare to Dream the Future.”

Well, the Future’s a fun place to hang out for a while. But suddenly your stomach’s growling. Maybe now would be a good time to sample all that international cuisine that’s available around World Showcase Lagoon. So you walk back around that pedestrian bridge and begin exploring the Americas.

(Westcot’s World Showcase is a little different than the Epcot version. Here, you won’t find separate countries, but countries grouped by regions. So, if you want to check out the international area, you have a choice of heading to the Americas, Europe, Asia as well as Africa & the Far East. Four distinct districts that try to span the globe. Today, you’ll begin your journey in the Americas.)

As you walk back across the pedestrian bridge, you can’t help but notice how cleverly Westcot is laid out. The buildings that form the Americas area (which also double as the main entrance to the park) have been done in an early 1900s style, reminiscent of the way New York City must have looked like at the turn of the century. Architecturally, these buildings have just enough in common with the buildings that make up Disneyland’s Main Street U.S.A. that the two theme parks blend together effortlessly. There are no jarring transitions for guests who are exiting one park to visit the other. It all flows together seamlessly.

Inside World Showcase, this sort of architectural blending continues. Instead of doing what the Imagineers who designed the original Epcot did (i.e.: building large, free-standing international pavilions with wide swaths of greenery separating each building from its neighbor), the team that designed Westcot put its buildings right next to one another. That way, you can — for example — see how Japanese architecture borrowed from Chinese design, which — in turn — influenced Indian ornamentation.

You also notice that Disney has obviously learned from the other mistakes it made with Epcot. There are fewer travelogue films to be seen here, but a lot more rides. Kids won’t complain about there being nothing to do in this park, particularly with attractions like “Ride The Dragon.” This steel coaster roars across the rooftops of the Asian section of World Showcase, following a track that’s designed to look like the Great Wall of China.

As you explore the many shops and exhibits you find in the park’s international area, your eye keeps being drawn to the top three floors of the six story buildings that ring World Showcase Lagoon. What a thrill it must be to have a room up there — in one of two new Disney Resort hotels, where guests can actually “live the dream” of staying inside a theme park.

I bet those rooms offer a great view of the nightly fireworks extravaganza.

Speaking of night, where did the day go? It seems like you just got to Westcot, yet it’s already time to head back home. You barely got to see half of this hyper-detailed theme park. I mean, how did you end up missing taking a trip on “The River of Time,” the park’s signature attraction? That 45 minute boat ride would have taken you all the way around the park, past elaborate audio animatronic recreations of great moments in history.

Oh well. I guess you’ll just have to catch that the next time.

You walk out of Westcot. And — while you are sorely tempted to catch that rock concert that’s currently playing in the Disneyland Arena (a 5,000-seat venue located just outside the entrance of Westcot, right next to Harbor Boulevard) — you know it’s really time to go home. That’s another one of the many attractions that will have to wait ’til the next time you visit the new and improved Disneyland Resort.

But — given all the new stuff that there is to see here — you’re sure you’ll be back soon.

The Promise of Westcot

You see. THAT’S what we missed out on. NOW do you understand all the endless griping you read about California Adventure as you’re out trolling the Internet?

This was a version of the Disneyland Resort that you could never have seen in one day. You would have — at the very least — needed three days: One to visit Disneyland “Classic,” one to visit Westcot, as well as an additional day to explore the new hotels, and to shop and dine at Disneyland Center.

This was exactly what Eisner wanted: Walt Disney World recreated in Anaheim in miniature. A world class resort built on a postage-stamp sized parcel of land. Best of all, in spite of the number of attractions the Imagineers had crammed into the project, the Disneyland Resort would not have seemed cramped. All the plazas, trees and fountains would have given guests the illusion that there was plenty of open space.

One of the things that really excited Eisner was that “Live the Dream” program, which would have allowed guests to stay in hotel rooms that were actually located inside Westcot’s World Showcase. Extensive survey work at Disneyland had showed that guests were willing to pay top dollar — $300 to $400 a night — to stay in these rooms. That would have made this part of the resort a tremendous money maker for the Walt Disney Company.

The beauty of this plan was that — in designing six story structures for World Showcase that housed shops, shows and restaurants on their first three floors and guest rooms towards the top — is that the Imagineers created a unique variation on Disneyland’s berm. The very height of these combination show buildings / hotels prevented guests from seeing out into the real world, perfectly preserving the sense that they had been transported to a different place.

The Westcot project seemed to have everything going for it. It had looks. It had style. It had the potential to make massive amounts of money, which to Michael Eisner’s way of thinking, is a lot more important than looks and style. It had Orange County officials drooling over the idea of hundreds of thousands of people putting off that WDW vacation in favor of visiting Disney’s newest resort in Anaheim.

There was just one slight flaw in this plan: No one had bothered to ask Disneyland’s neighbors — the folks who actually live in homes off of Katella and Ball Street — what they thought of all this development.

As it turns out, they had plenty to say.

Problems with Residents

There was no getting around it. Spacestation Earth was going to be impressive.

At 300 feet, Westcot’s centerpiece building was going to be the tallest structure in all of Orange County. As big as a 23-story skyscraper, but round and covered in gold. Shimmering under the Californian sun, it would dazzle your eye and be visible for miles around.

Impressive, yes. But would you really want one towering over your backyard?

That was the problem Curtis Sticker and Bill Fitzgerald had. As long-time Anaheim residents, they had grown accustomed to the nightly crackle of the fireworks over the Magic Kingdom. They had learned all the short cuts to get around traffic jams on Interstate 5. That’s just what you had to do when the Mouse was your neighbor.

But now here comes Westcot with its 4,600 new hotel rooms, its 17,500 new employees, and its 300 foot tall golden ball. All those dramatic changes to Disneyland were bound to have an impact on the local community, right?

That’s what Sticker and Fitzgerald thought. But when they tried to voice their concerns about the project during a June 1991 Wescot public forum all they got was Disney’s dog and pony show.

When asked about traffic flow, the Mouse pointed to the project’s two huge parking garages (which on the model loomed over Fitzgerald’s neighborhood like the Great Wall of China.) “They’ll be the largest parking garages in the whole world,” the Disney Guest Relations spokesperson squeaked proudly.

When asked about noise, the gosh-how-cute spokesperson tried to deflect the crowd’s concerns by pointing out the Disneyland amphitheater. “It’ll seat 5000,” she said, “And we’ll get neat people like Neal Diamond and Barry Manilow to come there and play.” (Sticker couldn’t help but notice given the way that amphitheater was situated on Disney property that the natural acoustics of the place would drive a lot of noise from those concerts right into his neighborhood.)

“What about our schools?” the neighbors asked. “Won’t they get swamped when the children of those new 17,500 cast members try to enroll?” This was the cue for Disney media relations staff to play up the educational aspects of Westcot. “Your kids will be able to take field trips here and learn all about other lands as they tour World Showcase. And have you noticed Spacestation Earth? That will have lots of science exhibits in it, too.”

Fitzgerald and Sticker had heard enough. It was obvious that Disneyland thought its Anaheim neighbors were a bunch of complete idiots, the types of yokels that could be distracted from voicing their petty concerns by lots of bright, happy talk about the wonders of Westcot. “Oooh! Look at Spacestation Earth! It’s so big and shiny.”

Let this be a lesson to Mickey: Never piss off a suburbanite.

Gathering the Troops

In the days that followed, Fitzgerald and Sticker met with other area residents who were equally bothered by the Mouse’s seemingly cavalier attitude towards the concerns of the local community. They felt something should be done to make Eisner aware that the locals weren’t too thrilled with his ambitious new plans for Anaheim. Someone suggested that they get a petition going, maybe form a group.

This is how the Anaheim Homeowners for Maintaining the Environment (“Anaheim HOME”) rose up in Spring 1992 and grew to bite Disney squarely in the ass. 1,600 members strong, this neighborhood-rights group quickly became a force for Disney to reckon with. Anaheim HOME did things that terrified the Mouse, and that forever changed the way Disney did business in Orange County.

Take for instance the tickets scandal. For 38 years, one of the nicest perks Anaheim city employees got when they worked in the Mayor’s office was free tickets to Disneyland. You just told the Mayor’s secretary when you wanted to go, and she made the call to Disneyland’s City Hall. Your passes would be waiting at Guest Relations when you arrived at the park.

Anaheim HOME got wind of this decades old practice. Since the people who worked in the Mayor’s office were obviously going to have some influence over the Anaheim Planning Commission (the folks who’d actually say “yea” and “nay” to Disneyland’s expansion plans), wouldn’t it stand to reason that giving free tickets to the Mayor’s staff could somehow be viewed as influence peddling by the Mouse? Kind of like offering them a bribe?

Anaheim HOME clued the local media in to the free tickets scam. In the firestorm that followed, hundreds of Orange County employees had their reputations sullied for allegedly taking illegal gifts from the Walt Disney Company. The Mayor’s office was forced to hand down an official edict: no city employee would ever be allowed to accept free tickets — or free anything — from Disneyland ever again. It was the end of an era.

It was not, however, the end of Anaheim HOME’s guerilla tactics in its attempts to make the public aware that the Mouse was one awful neighbor. Guests driving into the Disneyland parking lot during Christmas Week 1993, had to actually roll through a Anaheim HOME picket line. As guests slowed down, they were offered a leaflet detailing the less savory aspects of Disney’s expansion plans.

As you might imagine, Michael Eisner didn’t have a happy holiday when news of this got back to him.

Countering the Negative Publicity

Disney tried to turn around the bad buzz about its Disneyland resort project. The Mouse quietly recruited prominent local businessmen like KTLA’s Ed Arnold, Coporate Bank Chairman Stan Pawlowski and Pacific Bell executive Reed Royalty to head a pro-Disney organization that area residents would be asked to join.

This organization, which came to be known as “Westcot 2000,” meant well. But the overly-polished and professional way Arnold, Pawlowski and Royalty produced their pro-Disney rallies easily gave away the Mouse’s influence over the group. One infamous “rah-rah” session was actually staged in the Disneyland Hotel convention center. Though 4000 people were in attendance singing the praises of the Walt Disney Company, it was the Anaheim HOME team, with its dozen volunteers, carrying signs that trumpeted “Disney Greed” as they picketed out in front of the hotel, that got all the TV coverage.

It seemed that no matter what the Mouse tried to do to turn around Wescot it just couldn’t catch a break. Take, for example, the giant parking garage that Disney was planning to build for the expanded Disneyland resort. Through extensive lobbying in the US House and Senate, the Mouse was able to persuade Congress in the summer of 1994 to pick up $25 million in construction costs toward the project. Seems like a pretty clever thing to do, right?

Not in light of what happened next. Later that fall, word got out that Representative Bob Carr (D. – Michigan), one of the authors of that appropriations bill, had accepted sizable campaign contributions from several senior Disney executives. Mind you, nobody did anything illegal. But it still didn’t make the Mouse — or Westcot — look good.

Euro Disney and Scaling Back

In the meantime, big problems were flaring up elsewhere the Disney empire. Euro Disney, what many Mouska-fans had figured would be a sure-fire success, floundered immediately after its April 1992 grand opening. It took Walt Disney Attractions president Judson Green and a cadre of accountants almost 18 months to clear up the resort’s cash flow problems. Finally, in October 1994, a workable financial restructuring plan was in place and Euro Disney, now renamed Disneyland Paris, slowly inched its way out of the red.

Now, it’s important to understand that in the 18 months it took to get the Euro Disney bail-out strategy in place, Michael Eisner really lost his taste for huge ambitious Disney theme park projects. He saw how Euro Disney had been dragged down by the six luxury hotels that surrounded the theme park and thought: “I’m never going to overbuild another Disney resort ever again.”

So the word came down in Spring of 1993. Michael wanted the Imagineers to scale back the Disneyland Resort plans. How far did Eisner want the plan rolled back? The project’s original specs called for 4,600 new hotel rooms to be built within the Disneyland Resort. Westcot 2.0 would feature only 1,000 new hotel rooms.

Spacestation Earth? Gone. In its place was a new icon: a 300-foot-tall, tapered, white spike. At its base, the spike featured a 35-foot-tall, blue-and-green, revolving globe. Not exactly awe inspiring sounding, is it?

The Mouse also had to make numerous changes to its original Disneyland Resort master plan to appease the irate locals. It seems that Disney, on their Westcot overview site plan map, listed the company’s plans for parcels of property the Mouse didn’t actually yet own.

As you might guess, this last bit of news truly ticked off the owners of the Melodyland Christian Center and the Fujishige strawberry fields. Both of these parcels had been listed as possible locations for the Disneyland Resort’s second giant parking garage. This was odd, given that neither owner had any intention of selling his property to the Mouse.

In a particularly fiery letter dated June 1993, Carolyn Fujishige stated that her family “would never sell [its] property to the Disney Company or to anyone that is affiliated in any way to the Walt Disney Company.” Of course, one must remember never to say never. The Fujishige family, giving in after decades of pressure from the Mouse, finally sold its 52+ acres to the Walt Disney Company in August 1998 for an estimated $90 million. (I wonder what Carolyn’s cut of that windfall was? Anyhow …)

Making Westcot Go Away

On and on, year after year, Westcot’s problems kept hammering away at Eisner, draining his confidence and raising his doubts about the project. All he had wanted to do was recreate Orlando in Anaheim. How had this seemingly simple plan get thrown so far off track?

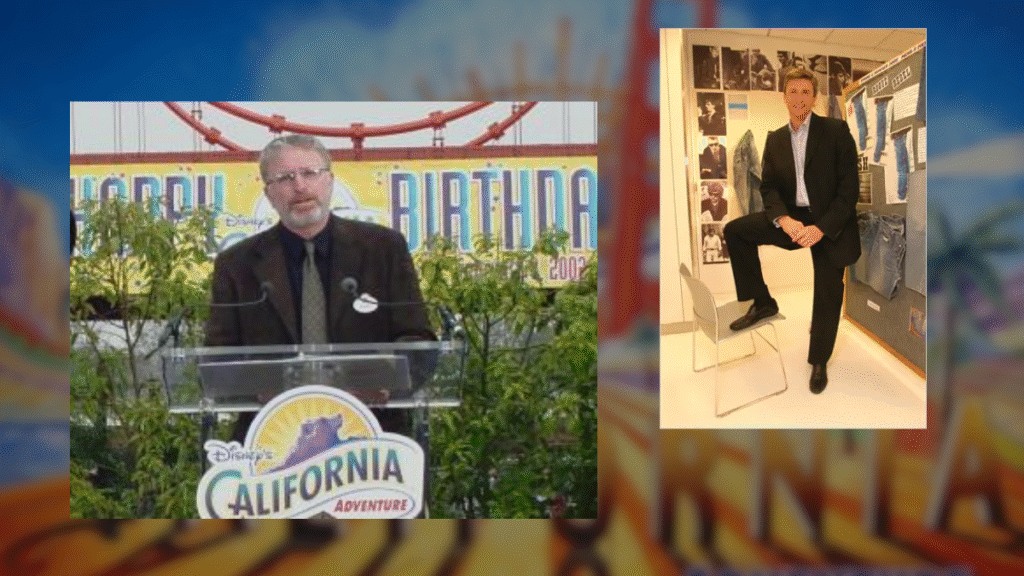

In the end, Eisner turned to his new hatchet man, Paul Pressler. A bright, young executive who had worked wonders with the company’s retail division, Pressler had recently moved over from the Disney Stores to head the Disneyland Resort.

Eisner told Pressler: “I’m tired of all the mess and bad press that’s associated with Westcot. Make it go away.”

So Pressler did.

On the day before Disneyland’s 40th birthday, Pressler called in the local media and broke the bad news: Disney was abandoning its plans to build Westcot, as well as scaling back all previously announced expansion plans for Disneyland.

When pressed for information about the Mouse’s future plans for Anaheim, Pressler said, “We’re going to build a second gate, absolutely … Our (Eisner’s / Pressler’s) vision is consistent. Make Disneyland the best resort we can. Certainly a second resort is part of that vision. My job is to figure out how to do it.”

Does that sound ominous?

It should.

Coming Up With a New Plan

Westcot was dead. Long live Westcot.

Eisner and his Imagineers had tried to do something bold, something ambitious in Anaheim. That didn’t fly with the locals or, in the end, make that much financial sense for the company.

But now the clock was ticking. CalTrans had already begun work on a multi-million dollar face-lift of Interstate 5. Once this six-year-long lane-widening, bridge-building and exit-ramp-constructing project was completed, folks could once again be able to zoom down the 5 to Anaheim to see …

What? Disney had persuaded the state to put all that money into highway improvements to help support their new expanded resort. Now that plan was in ruins. The Mouse had better come up with something quick. Otherwise Governor Pete Wilson and those fine folks up in Sacramento are going to be plenty pissed.

As you might understand, the pressure was on as Eisner held a design summit up at his Aspen retreat late that fall. Chief among those in attendance were senior Walt Disney Imagineering (WDI) officials Marty Sklar and Ken Wong, Disneyland President Paul Pressler as well as Imagineering rising star, Barry Braverman.

Braverman had recently come to Eisner’s attention because of the exemplary job he’d done putting together the “Innoventions” project at Epcot Center in Walt Disney World (WDW). Using just his tongue and a telephone, Braverman had persuaded many major American corporations to pay the Mouse to build and staff exhibits of their new products. By doing this, Barry had rethemed and redressed Future World’s entire Communicore area for virtually no money.

Sure, Epcot’s “Innoventions” might have looked more like a mall than a theme park attraction. What did that matter? Guests seemed to like the place. More importantly, it had been inexpensive to build and was even cheaper to run. That made Braverman look like a genius in Eisner’s eyes. Which is why Michael invited Barry to join WDI’s senior staff at this meeting in Aspen. Eisner was hoping that Braverman might be able to work some more of his budgetary magic on the Disneyland expansion project.

From the very start of the charrette, the group agreed about what Westcot’s main problem had been: The plans for Disneyland’s second gate had just gotten too big, and too unwieldy. In attempting to make sure the expansion plans met with the high quality of the existing park in Anaheim (arguably the best theme park in the whole Disney chain), the Imagineers had let the project get out of control.

This time around, the Mouse wouldn’t try and top America’s original theme park. Eisner wanted a second gate for Anaheim that the company could build quickly, but was still affordable. He wanted this new theme park to be a modest companion to Disneyland, rather than its flashy competitor. But, most importantly, this second Anaheim theme park had to be able to generate a huge cash flow for the Walt Disney Company from the very first day it opened.

Designing the Second Park

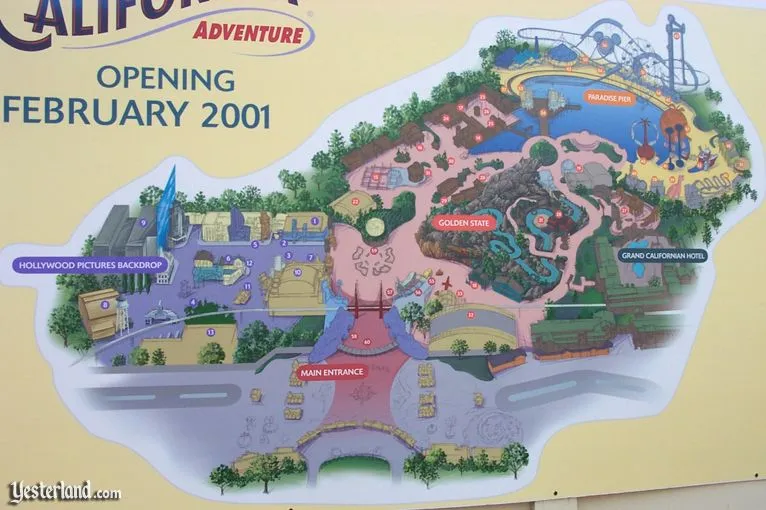

Let’s go over those design parameters again, shall we? Easy to build, but cheap to do. Must compliment — not compete with — Disneyland. And must be able to turn a profit as soon as the place opens.

With that assortment of meager ingredients, could you cook up a great theme park?

Well, at least the Imagineers tried. They talked about doing a smaller version of Disney Seas (too costly) or doing a scaled back Disney-MGM Studio theme park. (Why would folks want to visit a fake movie studio, when there are real ones to tour 30 miles up the road?) They also looked at building just Future World or just World Showcase. But — if they built that — guests would just complain that Anaheim had a half-assed version of WDW’s Epcot.

It was obvious that none of the ideas that Disney had used for its previous theme parks would work in this situation. So the team began attacking the problem from another angle: What was it that was missing from Disneyland? Why do guests leave the resort and continue their Southern Californian vacations elsewhere?

Well, that one seemed obvious. People left Disneyland because they wanted to see more of California. They wanted to walk along the Boardwalk at Venice Beach. They wanted to hike through the Redwoods in Sequoia National Forest. They wanted to ride the killer roller coasters at Magic Mountain, and take the tram tour at Universal Studios Hollywood. In short, these vacationers wanted to sample everything else the State of California had to offer.

For a moment, Eisner and his design team just sat there, blinking at each other. The answer to their problem couldn’t be that obvious, could it? A theme park that celebrated California. A place that recreated — in miniature — the best that the Golden State had to offer. Guests would no longer have to leave Anaheim to continue their Californian adventure (Oooh! Hang on to that! I think we just tripped over the title!). Everything they were looking for, and more, would be right next door to Disneyland.

That’s all Eisner had to hear. “That’s it,” he said. “Let’s build it.”

And that — swear to God — is how the concept for Disney’s California Adventure (DCA) theme park was born.

California Adventure

The project quickly went into overdrive from there. Since Pressler and Braverman were the first to suggest a California-based theme park, Eisner put them in charge of developing it. This, as events continue to unfold, might have proven to have been a mistake.

Braverman, who was just coming off his first big success with WDW’s “Innoventions” project, was anxious to see his star continue to rise within the Walt Disney Company. Eisner wanted a cheap park? Fine. Braverman planned to budget Disneyland’s proposed second gate so tightly that the blueprints would squeak.

But Pressler was also an ambitious man. He too was already plotting his next move up the Disney corporate ladder, perhaps parlaying his Disneyland presidency into something further up the food chain. But, to do that, he’d really have to deliver the goods on the Disneyland second gate project.

So Pressler took Braverman’s initial budget estimates … and slashed them by a third.

Okay, so now we’ve got two ambitious people, each out to impress upper management by delivering a low-budgeted project on a high-speed timetable. Can you say “recipe for disaster”? Sure you can.

No Imagineers for California Adventure?

Pressler and Braverman got the project off on the wrong foot when they announced that they didn’t want “Disney’s California Adventure” designed by WDI. Instead, they wanted Disneyland’s second gate to be created by the same folks who designed WDW’s hotels: the Disney Development Company (DDC).

What was the deal here? The Imagineers had, somewhat unfairly, taken the rap for all the cost over-runs Disney racked up on Euro Disney. Never mind that Eisner himself had suggested dozens of last minute changes to that park that had tacked on tens of millions of dollars in construction costs to the project. When the red ink started flowing in France, Uncle Mikey needed someone to blame. (Guess who he picked?) Pressler and Braverman wanted to deliver “Disney’s California Adventure” on time and under budget. Since DDC had a better reputation inside the company for meeting its deadlines and controlling costs, Pressler and Braverman wanted to give the park to it to develop.

When word of this got out, the Imagineers hit the roof. For over 40 years, WDI had designed every theme park, ride and attraction the Walt Disney Company held ever built. Now their jobs were to be usurped by the same guys who brought us the Dolphin and the Swan hotels at WDW?

No way.

Veteran Imagineer Chris Caradine (best known as the designer of WDW’s Pleasure Island) did more than just complain about this injustice. He circulated a letter to all of WDI’s senior architects, condemning Pressler and Braverman’s cost control maneuver. He then had all of these Imagineers sign the letter, which he then personally hand delivered to Eisner.

Concerned that his senior Imagineering staff was about to revolt, Eisner got the message. He called Braverman and Pressler into his office and told them that they had to use Imagineers to design Disneyland’s second gate.

This was the first of several short-sighted decisions that Pressler and Braverman made concerning “Disney’s California Adventure.” Individually, none of these decisions were bad enough to sink Disneyland’s second gate. But combined?

Well, let’s just say that there are a lot of folks at Walt Disney Imagineering who view DCA as an almost fatally flawed project.

Problems with Disney’s California Adventure

What exactly are the project’s problems? Some point to Pressler and Braverman’s decision not to develop many new rides and shows for DCA, but opting instead for a lot of attraction recycling.

While it was undoubtedly more cost-effective to take shows that have already proven popular at other Disney theme parks (like Disney-MGM’s “Kermit the Frog presents MuppetVision 3D” and Animal Kingdom’s “It’s Tough to Be a Bug”) and redress them a bit to fit in DCA, is this really the best long-range strategy?

Isn’t it possible that using old WDW shows could actually have a detrimental effect on Disneyland Resort’s attendance levels?

Think about it.

Wasn’t Eisner’s main reason for building a second gate at Disneyland to turn the company’s Anaheim holdings into a vacation destination like Walt Disney World? But why would folks from the East Coast fly all the way out to California just to see shows that they’d already seen — years earlier — in Orlando?

Don’t get me wrong. “MuppetVision 3D” (WDW debut: May 1991) as well as “It’s Tough to Be a Bug” (WDW debut: April 1998) are both fine shows. And there are millions of people west of the Rockies who’ve never seen these attractions and will happily make a special trip to Disneyland just to see Kermit and Flick in 3D.

But if Disney really wants to turn Anaheim into a destination resort like WDW, recycling old shows from Walt Disney World probably isn’t the smart way to go. Adding fresh new rides and attractions that are exclusive to DCA is the only way to guarantee tourists from both coasts will make a point of frequenting the park.

Speaking of rides, another problem a lot of Imagineers have with DCA are those off-the-shelf carnival-style attractions being used in Paradise Pier.

But it’s not for the reason you think.

Sure, the rides over here might look hokey and cheap. (And I can’t help wondering how Orange County feels, having spent all those millions, renovating and expanding its convention center into a state-of-the-art meeting facility, only to have Disney build a deliberately chintzy looking Ferris wheel and roller coaster in front of it.) But the rides are supposed to look that way, folks. This part of DCA pays tribute to those old amusement piers you used to find along the California coast.

And I know that it’s popular to bash this part of the park on the Web.

But I won’t.

Why? Because I like it. I think that Disney’s done a great job of recapturing the look and feel of an old turn-of-the-century seaside amusement park.

But you know what the real irony is? All the old cheesy-looking amusement piers disappeared because squeaky clean theme parks like Disneyland drove them out of business. So now here’s the Mouse, bringing the amusement pier back from the dead, with all its grubbiness intact.

But what do the Disney dweebs on the Web do? Complain loudly about how “cheesy” Paradise Pier looks. It’s supposed to look cheesy, guys. Get it? And — off-the-shelf or not — those old fashioned carny rides you’ll find along on DCA’s Paradise Pier will be a kick to ride.

Capacity

The real problem is capacity. These old fashioned rides are slow to load and unload. Even with their projected painfully short ride times (Example: Guests will supposedly only get 90 seconds to savor the low-tech thrills of the “Orange Stinger”), there’ll still be huge lines over in Paradise Pier.

Why? Because, on opening day, DCA is only going have only 22 rides and attractions. But Disney’s own attendance projections show that, on a typical summer day, 30,000 guests will be wandering around DCA, looking for things to do.

Editor’s Note: This article is an adaptation of an original Jim Hill Media Five Part Series “California Misadventure” (2000). Disney’s California Adventure opened on February 8, 2001 and years later saw a complete overhaul in 2012.

Think about it. Are you really going to be happy, having paid $40+ a head to get into DCA, only to stand in a two hour long line just to ride “Mullholland Madness?”

This is what worries the older Imagineers. During that first crucial summer of operation, guests will undoubtedly exit DCA — having spent most of their day standing in very long lines for the all-too-short attractions — then go home to tell their friends and neighbors about what an awful time they had at Disney’s new theme park. This is why WDI is pressuring Disney management to begin DCA’s Phase II construction NOW.

Pressler and Braverman honestly believe that they’re improving Disney’s bottom line by bringing DCA in on time and under budget. But where will the great savings be if Disney has to turn around and immediately begin pumping millions into the park in a desperate attempt to boost its hourly ride capacity?

WDI has reportedly repeatedly warned Disney’s top management team about DCA’s potentially fatal flaws. Privately, Eisner has evidently acknowledged that Disneyland’s second gate could be in for a rough couple of years. Even so, he expects DCA to make a lot of money for the company as well as eventually grow into a worthy companion to Disneyland.

Well, here’s hoping.

Myself? I’m hoping that — as I stroll into DCA on opening day — that the theme park is at least as intriguing as the story of its development and construction.

Doesn’t seem very likely now, does it?

THE END – for now…

Want more behind-the-scenes Disney stories? You can also hear more stories on The Disney Dish podcast, where Jim Hill and Len Testa explore Disney news and park history. Listen now at The Disney Dish on Apple Podcasts.

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment

The ExtraTERRORestrial Files

This article is an adaptation of an original Jim Hill Media Four Part Series “The ExtraTERRORestrial Files” (2000).

It was the attraction that was supposed to be the next big thing for the Disney theme parks. The show that would change forever how guests would think about the Mouse by mixing in-theater effects with 3D sound to create high-tech terror.

At least that was what was supposed to happen. But — instead of becoming a franchise attraction like Space Mountain, with different versions of the ride being built in Anaheim, Orlando, Tokyo and Paris — only one version of this Tomorrowland show ever made it off the drawing board.

“Alien Encounter.” Eight years after this hi-tech horror show first opened — then quickly closed for a mysterious six month revamp — this Disney World attraction still remains highly controversial in theme park circles. Many WDW fans consider this intense show to be the best thing WDI’s ever done. Other Disneyana enthusiasts — particularly those with small children — think that this horror show is horrible. They argue that something this scary just doesn’t belong in the Magic Kingdom.

Well, if you thought that “Alien Encounter” — the attraction — was scary … wait ’til you hear the terrifying behind-the-scenes tale of how this troubled Tomorrowland show was creates.

It begins on a dark night … where a dark man waits … with a dark purpose …

No. Wait. My mistake. That’s “Aladdin.”

Michael Eisner’s Plan for Theme Park Attendance

The “Alien Encounter” story actually begins back in September of 1984, when former Paramount studio head Michael Eisner first took control of Walt Disney Productions. Upon entering the Mouse House, one of Eisner’s first goals was to boost sagging attendance levels at the company’s theme parks. While it was obvious that Disney had a lock on the family audience, Michael believed that the Mouse’s parks lacked teen appeal. He based this opinion on his teenage son, Breck, who — when asked by his dad to join him a familiarization tour of Disneyland — reportedly said “That place is lame, Dad.”

Fearing that his son spoke for teens everywhere, Eisner quickly commissioned a marketing survey. Teenagers exiting Disneyland and the Magic Kingdom at Walt Disney World were asked what they thought the Mouse’s theme parks were missing. These teens reportedly said that they wanted more thrill-based attractions in the Disney parks, similar to what they could find at the “Six Flags” parks and Universal Studios.

Something radical to cut through all the sweetness.

With the results of this survey in hand, Eisner ordered WDI to immediately begin development of several radical new shows that could be added to the Disney theme parks. Buoyed by the acclaim “Star Tours” had received when that simulator ride first opened at Disneyland in January 1987, the Imagineers toyed with the idea of bringing a few more of 20th Century Fox’s sci-fi creatures on board at the company’s theme parks.

But these wouldn’t be George Lucas’s cute and cuddly “Star Wars” creations. The Imagineers wanted the black and slimy, acid drooling monsters from the hugely popular “Alien” movie series.

Bringing “Alien” to Disney Parks

Strange but true, folks. Using the story and settings from the first “Alien” film as a starting point, the Imagineers cooked up a concept for a hi-tech interactive attraction they called “Nostromo.” On this proposed attraction, visitors would have rolled through the darkened corridors of the Nostromo — the spaceship Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) piloted in the first “Alien” film — riding inside of heavily armored vehicles. Armed with laser cannons, these folks were supposedly on a rescue mission. Their goal was to find the missing members of Nostromo’s crew as well as rid the spaceship of all alien intruders.

“Nostromo” certainly was a radical new idea for a Disney theme park attraction. Perhaps too radical. In the end, WDI opted not to go forward with the “Alien” ride project. Why for? Well, while they recognized that “Nostromo” would have been a thrilling addition to any theme park, certain senior members of the Imagineering staff voiced concerns that any ride that featured the “Alien” monsters might be too dark and intense for Disney’s family-based audience. These same Imagineers were also troubled by the image of children blasting space monsters with laser cannons. “Walt would never have approved of a ride like this,” they grumbled. So WDI’s first stab at an “Alien” attraction ended up being blown out an airlock. This show concept never made it off the drawing board.

Well, even though “Nostromo” was a no go, some good did eventually come out of the aborted attraction. 13 years after work on the interactive “Alien” ride-thru show had been halted, Tomorrowland finally got its laser-cannon, alien-blasting attraction … but in a much more family friendly form. WDW’s “Buzz Lightyear Space Ranger Spin” uses many of the concepts that the Imagineers created for their first “Alien” show.

Plus all the development work WDI did on the proposed “Nostromo” attraction did make Disney executives aware of the inherent in-park value of the “Alien” monsters. So the Mouse decided to license 20th Century Fox’s characters for use in its theme parks. Ripley and the “Alien” monsters were featured prominently in the “Great Movie Ride” when that attraction opened at the Disney-MGM Studios Theme Park in May 1989. But except for the first few years of the Fox licensing deal that was the extent of Disney’s use of the “Alien” characters in their theme parks.

Updating “Mission to Mars”

A year or so later, some youngish Imagineers were wondering what to do with “Mission to Mars.” Eisner had tasked them to come up with a thrilling new replacement for this lame old Tomorrowland show. He wanted something just as exciting as “Star Tours,” but in a sit-down theater setting.