Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment

A Chilly Season on the Great White Way

Seth Kubersky returns from a recent trip to the Great White Way and shares his thoughts about two poorly reviewed musicals: “The Boy from Oz” and “Taboo.”

When most people think of holiday time in New York City, they see images of warmth and nostalgia. The majestic balloons of the Macy’s parade, the glowing tree at Rockefeller Center, warm chestnuts from a street cart vendor. But the first thing I think of is the cold. Bitter, bone-breaking cold. Six years of living in Florida has thinned my blood to the point that a week-long visit with the family feels like six months in the arctic. The electronic time-and-temperature hovering over Times Square may read 40 degrees, but when the wind whips down the canyons of Broadway, it feels like less than half of that.

But as cold as this Thanksgiving might have been for me, it’s been even colder for producers of Broadway shows. This fall season has been the most brutal in recent memory for new productions. Ellen Burstyn’s “Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All” closed 24 hours after opening. “Six Dance Lessons in Six Weeks” and “Jackie Mason: Laughing Room Only” had similarly short runs, and “Bobbi Boland” didn’t even make it to opening night. The verdict is still out on the long-term prospects for “Wicked”, a revisionist prequel to the Wizard of Oz. The only genuine hit this year with both critics and audiences has been “Avenue Q”, the brilliant Sesame Street satire that transferred from Off-Broadway last spring. A visit to TKTS, the discount booth that sells unsold tickets at half price, tells the story: nearly every show, save a few long-running hits like “The Lion King” and “The Producers”, had tickets available during what is normally a busy holiday weekend.

In the middle of all this, two strikingly similar shows opened. The markedly different reactions to these two shows, both by the press and at the box office, illustrates how conventional wisdom, rather than talent or quality, is what ultimately makes or breaks a show in New York. Both are biographical musicals, told in flashback, about the life of a gay pop musician in the 1980’s. Both feature musical scores written by the subject, and feature name-brand stars in a leading role. Both have received less than glowing reviews from the New York critics. But one is regarded as a relative success in this dismal Broadway season, with decent word-of-mouth and healthy box office. The other is being openly derided in both the critical and popular press as a spectacular flop, and its name is quickly becoming synonymous with “epic disaster”. One is an amusing trifle that is pleasant enough, but quickly fades from the mind, while the other is ambitious, moving, and genuinely deserving of a life beyond its current incarnation. And you might be very surprised to learn which is which.

The first show is “The Boy from Oz”, the story of Peter Allen as portrayed by Hugh Jackman. At the risk of committing musical-theater heresy, I didn’t know Peter Allen from Peter Parker before seeing the show. It turns out Allen was a singer-performer from Australia (the “Oz” of the title) who played an opening act for Judy Garland, married her daughter Liza Minnelli, had a successful nightclub act, and wrote a number of award-winning songs. He was also gay (apparently a common theme among Liza’s husbands) and died of AIDS in 1992.

The story is narrated by Allen, looking back over his life. Amusing vignettes from his experiences in show biz alternate with his songs, which are shoehorned into the plot with limited success. I only recognized a handful of the numbers, namely “The Theme from Arthur” and “Don’t Cry Out Loud”, and found most of the songs inoffensive but unmemorable. Worse, they violate the cardinal rule of musical theater, in that they express things that have already been stated, and don’t advance the plot in any meaningful way. The supporting cast is fine, particularly Isabella Keating and Stephanie J. Block, who contribute eerie wax-museum impressions of Garland and Minnelli. Jarrod Emick is also memorable in his brief second-act roll as Allen’s boyfriend. The only true standout supporting player is the young Mitchel David Federan, who steals the show with an opening number song-and-dance routine as a pre-teen Allen. Even the sets, costumes, and choreography, while competent, are underwhelmingly minimal for such a larger-than-life story.

What saves this show from disaster is Hugh Jackman’s performance as Peter Allen. American fans who know him from his blockbuster movies might wonder if he can really sing and dance, much less play piano with those adamantium claws protruding from his knuckles. The answer, as anyone who saw his performance in London’s “Oklahoma!” (recently televised on PBS) can testify, is “yes, and how!” Jackman is charming and engaging from the opening moments, with a powerful singing voice and polished dance moves. Most importantly, he has the stage presence and charisma to sustain an audience’s attention through what is a fairly thin story. Unlike many movie stars who perform on Broadway, Jackman shows astounding endurance, staying on stage nearly every minute of the play. He also seems remarkably un-self-conscious about his macho screen image, capturing Allen’s flamboyant mannerisms with flair and flirting equally with male and female audience members.

Ultimately, while the show survives on Jackman’s charms, it lacks in depth or complexity. Aside from an 11th-hour revelation of childhood trauma, there is little shown of Allen’s psychological reality. It’s hard to tell if he kept his dark side remarkably well hidden, or if there simply wasn’t anything more to him than his stage persona. Jackman receives well-deserved standing ovations for the energy and likeability of his performance, but I walked out knowing nothing about the real Peter Allen that I couldn’t have learned from a 1-paragraph bio. The show is worth seeing (but not a full price) for Jackman alone, but I can’t see it having any staying power once he goes back to Hollywood.

“Taboo” is in many ways the mirror-universe dark twin of “The Boy from Oz”. Like “Oz”, it charts the life of a gay pop-music icon. In both, the first act chronicles his rise from obscurity to the first tastes of success, while in the second he succumbs to the excesses of fame. In both, there is an untimely death from AIDS, followed by an uplifting finale of hope and redemption through art.

The subject of “Taboo” is George O’Dowd, better known as Boy George, lead singer of the 80’s pop group Culture Club. His story is narrated in flashback by Philip Salon, a nightclub impresario who claims to have discovered Boy George. Salon’s account is constantly challenged by a second narrator, Big Sue, making for a hilarious exploration of the flexible nature of memory. We see George’s rise from coat checker to pop star, and his subsequent public descent into heroin addiction. Running parallel to George’s story is that of Leigh Bowery, an outrageous performance artist and designer played by the real George O’Dowd. This bit of casting, coupled with lead actor Euan Morton’s striking resemblance to the young Boy George, leads to such surreal delights as O’Dowd telling his younger self that “Karma Chameleon” is a terrible song that will never go anywhere.

The cast of “Taboo” is nearly uniformly excellent. Euan Morton not only looks like the 80’s-era Boy George, but sings like him too. He gives the performance an unexpected depth and vulnerability under the makeup. Even better is Raul Esparza as Salon. Raul’s theatricality and vocal contortions make him a love-it-or-hate-it performer, and I fall squarely in the love-it camp. He brings the same blend of sinister mystery and raw power that made him the best Riff Raff since Richard O’Brien created the role in “The Rocky Horror Show”. Here, he nearly steals every scene he’s in, only to be undercut by the earthy and profane Big Sue. As portrayed at the performance I saw by understudy Brooke Elliott, Sue is the most human character, a cynical romantic, with a stunning solo number in the second act. Surprisingly, the weakest link performance-wise is O’Dowd himself. He is heavy, stiff, and his voice is a croaking shadow of its former self, particularly in the first act. He seems mainly to exist in the show to display one astounding costume design after another.

But if George O’Dowd the actor is a disappointment, George O’Dowd the composer is a revelation. Though I grew up in the 80’s, I largely ignored the pop music of the time. While my peers were obsessing over Michael Jackson and Madonna, my Walkman was playing the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. I could probably hum a few bars of “Karma Chameleon” and “Do You Really Want to Hurt Me”, but I was never a fan of Culture Club. While both those songs are briefly heard in “Taboo”, along with an excerpt from “Church of the Poison Mind”, they are the exception. The rest of the score consists of hauntingly beautiful ballads and rocking techno-flavored dance numbers. The scores for “Urinetown” and “Avenue Q” are wittier, but “Taboo” has the most moving and memorable new melodies of any recent Broadway show. The nearest shows one can compare it to in style are “Aida” and “Rent”, and this blows both of those over-rated scores out of the water. If “Taboo” fails before a cast album is recorded, it would be a great tragedy, because these performances and this music need to be preserved.

“Taboo” is not without its flaws. While the music is consistently wonderful, the book is less so. Charles Busch, author of “Vampire Lesbians of Sodom”, has written some beautifully bitchy dialogue, but the structure is uneven, and the tone becomes abruptly dark in the second act. The show’s biggest flaw, as pointed out by all the critics, is that Boy George’s story never intersects with Leigh Bowery’s. As a result, you have two separate plots that alternate, with only a few characters that cross over between them. This wouldn’t be a problem if the stories commented on each other in a thematically meaningful way, but the connection never really becomes clear. In truth, this isn’t a fatal flaw, though the way critics have harped on it would make you think it ruins the show. Other elements that have been derided critically, such as the choreography, the over-the-top costume designs, and a video tribute to the real-life Bowery, I found to be assets to the show.

So why has the lesser of these two shows received a free pass from the press, and is in the top-5 for ticket sales, while the other is openly mocked and struggling financially? I must admit that the reviews led me to “Taboo” with a gleeful sense of schadenfreude. I never had the chance to see “Carrie” or “Legs Diamond”, so I figured this was my chance to be able to tell my children I saw one of the biggest train wrecks in Broadway history. Imagine my surprise when I turned to my seat-mate at intermission and said, “You know, this is pretty damn good”. If you had told me when I walked in that I’d be giving a standing ovation at the curtain, I’d never have believed you, but there I was.

What could make a show that is clearly so much better than many of the successes on Broadway such a pariah among the press?

Much of the blame can probably be laid at the feet of its producer, Rosie O’Donnell. This is a woman badly in need of new publicist. Ever since the cancellation of her TV show, and especially with her highly-publicized lawsuit against her former magazine partner, she’s been on a path of self-destruction. Giving the middle finger to critics in the audience at a recent performance didn’t help her any either. But Rosie is far from the first prickly producer, though being a household name and a woman makes her a more inviting target than most.

Also damaging was the widely-discussed revisions to the show during rehearsals and previews, and a near-mutiny by some cast members. But the truth is that many shows go through growing pains like these, and come out stronger for it. A responsible reviewer should evaluate the final product, and not simply regurgitate tabloid gossip.

Perhaps there is a darker and more disturbing reason for the abuse this show has suffered. American culture as a whole has become much more accepting of gay people and gay culture, and no city is more gay-friendly than New York. You can’t turn on the TV without seeing “Will & Grace” or “*** Eye for the Straight Guy”, and the trend has been discussed endlessly in the press. But the gays that the mainstream accepts are largely safe and neutered. The fashion and attitude associated with homosexuality might be embraced by the larger culture, but the sexuality and politics are not.

This might be the essential difference between the superficially similar “Boy from Oz” and “Taboo”. While the former is informed by the safe camp that appealed to Peter Allen’s straight female audience, the latter embraces the anarchic punk culture that thrived in the underground club scene of Boy George’s London. Or, to use the semiotics of modern activism, Peter Allen was “gay”, but Boy George was “***”.

This essential difference, both in the subjects and their shows, may help explain why the lesser show will probably outlast the better one. After all, New York is the capital of capitalism, and you can’t stay open on Broadway unless you can sell tickets to the blue-hair tourists. It’s just as shame that the press can’t stop bashing “Taboo”, and instead help those tourists look past the unconventional exterior to see the beauty at its heart.

History

The Evolution and History of Mickey’s ToonTown

Disneyland in Anaheim, California, holds a special place in the hearts of Disney fans worldwide, I mean heck, it’s where the magic began after all. Over the years it’s become a place that people visit in search of memorable experiences. One fan favorite area of the park is Mickey’s Toontown, a unique land that lets guests step right into the colorful, “Toony” world of Disney animation. With the recent reimagining of the land and the introduction of Micky and Minnies Runaway Railway, have you ever wondered how this land came to be?

There is a fascinating backstory of how Mickey’s Toontown came into existence. It’s a tale of strategic vision, the influence of Disney executives, and a commitment to meeting the needs of Disney’s valued guests.

The Beginning: Mickey’s Birthdayland

The story of Mickey’s Toontown starts with Mickey’s Birthdayland at Walt Disney World’s Magic Kingdom. Opened in 1988 to celebrate Mickey Mouse’s 60th birthday, this temporary attraction was met with such overwhelming popularity that it inspired Disney executives to think bigger. The idea was to create a permanent, immersive land where guests could step into the animated world of Mickey Mouse and his friends.

In the early ’90s, Disneyland was in need of a refresh. Michael Eisner, the visionary leader of The Walt Disney Company at the time, had an audacious idea: create a brand-new land in Disneyland that would celebrate Disney characters in a whole new way. This was the birth of Mickey’s Toontown.

Initially, Disney’s creative minds toyed with various concepts, including the idea of crafting a 100-Acre Woods or a land inspired by the Muppets. However, the turning point came when they considered the success of “Who Framed Roger Rabbit.” This film’s popularity and the desire to capitalize on contemporary trends set the stage for Toontown’s creation.

From Concept to Reality: The Birth of Toontown

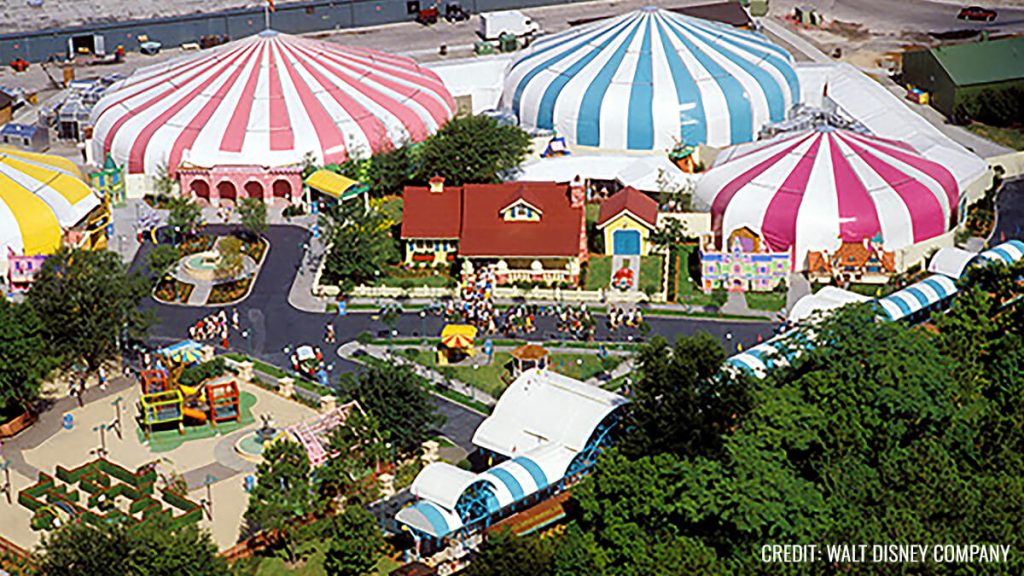

In 1993, Mickey’s Toontown opened its gates at Disneyland, marking the first time in Disney Park history where guests could experience a fully realized, three-dimensional world of animation. This new land was not just a collection of attractions but a living, breathing community where Disney characters “lived,” worked, and played.

Building Challenges: Innovative Solutions

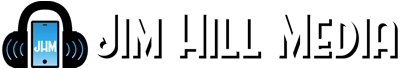

The design of Mickey’s Toontown broke new ground in theme park aesthetics. Imagineers were tasked with bringing the two-dimensional world of cartoons into a three-dimensional space. This led to the creation of over 2000 custom-built props and structures that embodied the ‘squash and stretch’ principle of animation, giving Toontown its distinctiveness.

And then there was also the challenge of hiding the Team Disney Anaheim building, which bore a striking resemblance to a giant hotdog. The Imagineers had to think creatively, using balloon tests and imaginative landscaping to seamlessly integrate Toontown into the larger park.

Key Attractions: Bringing Animation to Life

Mickey’s Toontown featured several groundbreaking attractions. “Roger Rabbit’s Car Toon Spin,” inspired by the movie “Who Framed Roger Rabbit,” became a staple of Toontown, offering an innovative ride experience. Gadget’s Go-Coaster, though initially conceived as a Rescue Rangers-themed ride, became a hit with younger visitors, proving that innovative design could create memorable experiences for all ages.

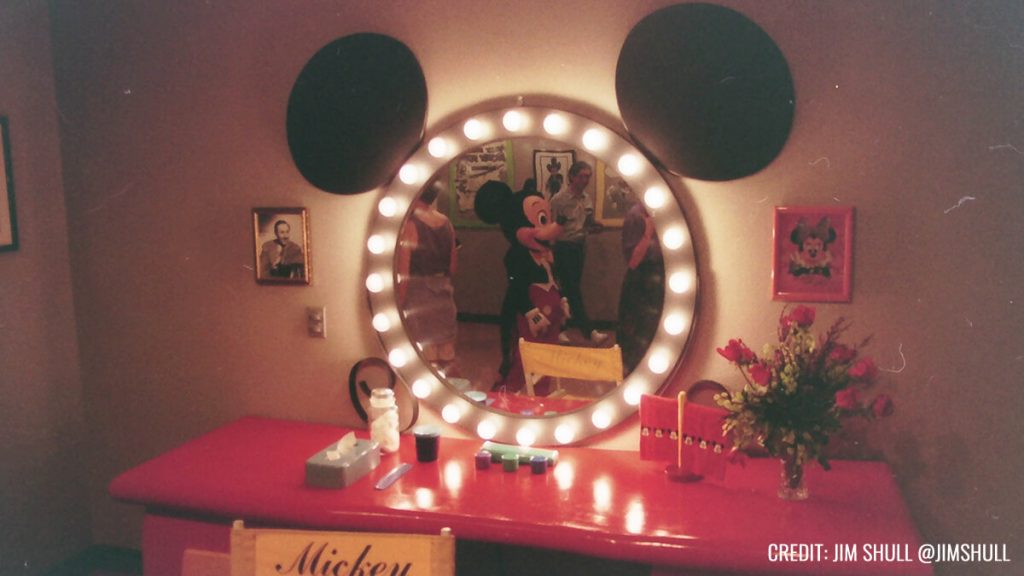

Another crown jewel of Toontown is Mickey’s House, a walkthrough attraction that allowed guests to explore the home of Mickey Mouse himself. This attraction was more than just a house; it was a carefully crafted piece of Disney lore. The house was designed in the American Craftsman style, reflecting the era when Mickey would have theoretically purchased his first home in Hollywood. The attention to detail was meticulous, with over 2000 hand-crafted, custom-built props, ensuring that every corner of the house was brimming with character and charm. Interestingly, the design of Mickey’s House was inspired by a real home in Wichita Falls, making it a unique blend of real-world inspiration and Disney magic.

Mickey’s House also showcased Disney’s commitment to creating interactive and engaging experiences. Guests could make themselves at home, sitting in Mickey’s chair, listening to the radio, and exploring the many mementos and references to Mickey’s animated adventures throughout the years. This approach to attraction design – where storytelling and interactivity merged seamlessly – was a defining characteristic of ToonTown’s success.

Executive Decisions: Shaping ToonTown’s Unique Attractions

The development of Mickey’s Toontown wasn’t just about creative imagination; it was significantly influenced by strategic decisions from Disney executives. One notable input came from Jeffrey Katzenberg, who suggested incorporating a Rescue Rangers-themed ride. This idea was a reflection of the broader Disney strategy to integrate popular contemporary characters and themes into the park, ensuring that the attractions remained relevant and engaging for visitors.

In addition to Katzenberg’s influence, Frank Wells, the then-President of The Walt Disney Company, played a key role in the strategic launch of Toontown’s attractions. His decision to delay the opening of “Roger Rabbit’s Car Toon Spin” until a year after Toontown’s debut was a calculated move. It was designed to maintain public interest in the park by offering new experiences over time, thereby giving guests more reasons to return to Disneyland.

These executive decisions highlight the careful planning and foresight that went into making Toontown a dynamic and continuously appealing part of Disneyland. By integrating current trends and strategically planning the rollout of attractions, Disney executives ensured that Toontown would not only capture the hearts of visitors upon its opening but would continue to draw them back for new experiences in the years to follow.

Global Influence: Toontown’s Worldwide Appeal

The concept of Mickey’s Toontown resonated so strongly that it was replicated at Tokyo Disneyland and influenced elements in Disneyland Paris and Hong Kong Disneyland. Each park’s version of Toontown maintained the core essence of the original while adapting to its cultural and logistical environment.

Evolution and Reimagining: Toontown Today

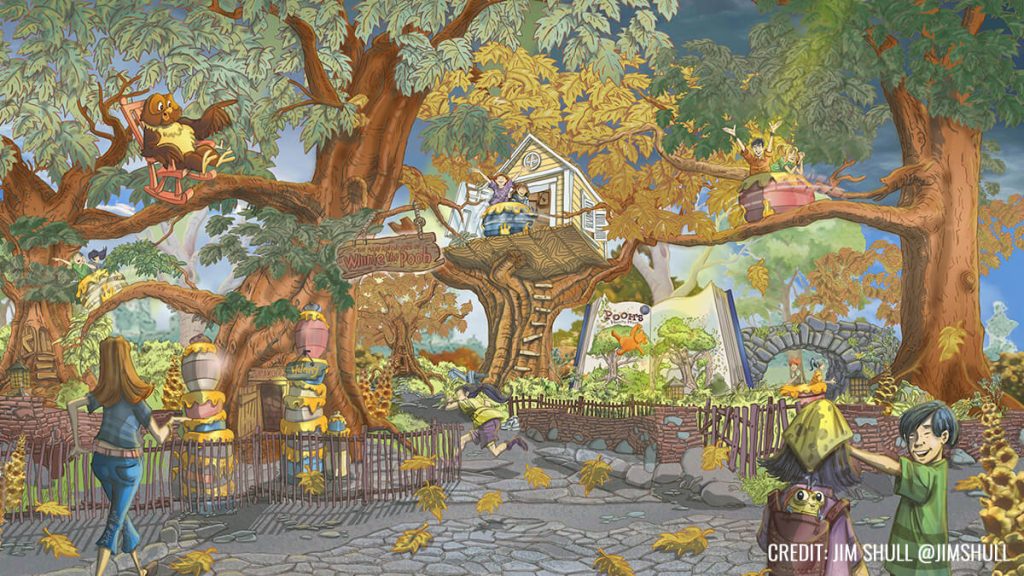

As we approach the present day, Mickey’s Toontown has recently undergone a significant reimagining to welcome “Mickey & Minnie’s Runaway Railway” in 2023. This refurbishment aimed to enhance the land’s interactivity and appeal to a new generation of Disney fans, all while retaining the charm that has made ToonTown a beloved destination for nearly three decades.

Dive Deeper into ToonTown’s Story

Want to know more about Mickey’s Toontown and hear some fascinating behind-the-scenes stories, then check out the latest episode of Disney Unpacked on Patreon @JimHillMedia. In this episode, the main Imagineer who worked on the Toontown project shares lots of interesting stories and details that you can’t find anywhere else. It’s full of great information and fun facts, so be sure to give it a listen!

History

Unpacking the History of the Pixar Place Hotel

Pixar Place Hotel, the newly unveiled 15-story tower at the Disneyland Resort, has been making waves in the Disney community. With its unique Pixar-themed design, it promises to be a favorite among visitors.

However, before we delve into this exciting addition to the Disneyland Resort, let’s take a look at the fascinating history of this remarkable hotel.

The Emergence of the Disneyland Hotel

To truly appreciate the story of the Pixar Place Hotel, we must turn back the clock to the early days of Disneyland. While Walt Disney had the visionary ideas and funding to create the iconic theme park, he faced a challenge when it came to providing accommodations for the park’s visitors. This is where his friend Jack Wrather enters the picture.

Jack Wrather, a fellow pioneer in the television industry, stepped in to assist Walt Disney in realizing his dream. Thanks to the success of the “Lassie” TV show produced by Wrather’s company, he had the financial means to build a hotel right across from Disneyland.

The result was the Disneyland Hotel, which opened its doors in October 1955. Interestingly, the early incarnation of this hotel had more of a motel feel than a hotel, with two-story buildings reminiscent of the roadside motels popular during the 1950s. The initial Disneyland Hotel consisted of modest structures that catered to visitors looking for affordable lodging close to the park. While the rooms were basic, it marked the beginning of something extraordinary.

The Evolution: From Emerald of Anaheim to Paradise Pier

As Disneyland’s popularity continued to soar, so did the demand for expansion and improved accommodations. In 1962, the addition of an 11-story tower transformed the Disneyland Hotel, marking a significant transition from a motel to a full-fledged hotel.

The addition of the 11-story tower elevated the Disneyland Hotel into a more prominent presence on the Anaheim skyline. At the time, it was the tallest structure in all of Orange County. The hotel’s prime location across from Disneyland made it an ideal choice for visitors. With the introduction of the monorail linking the park and the hotel, accessibility became even more convenient. Unique features like the Japanese-themed reflecting pools added to the hotel’s charm, reflecting a cultural influence that extended beyond Disney’s borders.

Japanese Tourism and Its Impact

During the 1960s and 1970s, Disneyland was attracting visitors from all corners of the world, including Japan. A significant number of Japanese tourists flocked to Anaheim to experience Walt Disney’s creation. To cater to this growing market, it wasn’t just the Disneyland Hotel that aimed to capture the attention of Japanese tourists. The Japanese Village in Buena Park, inspired by a similar attraction in Nara, Japan, was another significant spot.

These attractions sought to provide a taste of Japanese culture and hospitality, showcasing elements like tea ceremonies and beautiful ponds with rare carp and black swans. However, the Japanese Village closed its doors in 1975, likely due to the highly competitive nature of the Southern California tourist market.

The Emergence of the Emerald of Anaheim

With the surge in Japanese tourism, an opportunity arose—the construction of the Emerald of Anaheim, later known as the Disneyland Pacific Hotel. In May 1984, this 15-story hotel opened its doors.

What made the Emerald unique was its ownership. It was built not by The Walt Disney Company or the Oriental Land Company (which operated Tokyo Disneyland) but by the Tokyu Group. This group of Japanese businessmen already had a pair of hotels in Hawaii and saw potential in Anaheim’s proximity to Disneyland. Thus, they decided to embark on this new venture, specifically designed to cater to Japanese tourists looking to experience Southern California.

Financial Challenges and a Changing Landscape

The late 1980s brought about two significant financial crises in Japan—the crash of the NIKKEI stock market and the collapse of the Japanese real estate market. These crises had far-reaching effects, causing Japanese tourists to postpone or cancel their trips to the United States. As a result, reservations at the Emerald of Anaheim dwindled.

To adapt to these challenging times, the Tokyu Group merged the Emerald brand with its Pacific hotel chain, attempting to weather the storm. However, the financial turmoil took its toll on the Emerald, and changes were imminent.

The Transition to the Disneyland Pacific Hotel

In 1995, The Walt Disney Company took a significant step by purchasing the hotel formerly known as the Emerald of Anaheim for $35 million. This acquisition marked a change in the hotel’s fortunes. With Disney now in control, the hotel underwent a name change, becoming the Disneyland Pacific Hotel.

Transformation to Paradise Pier

The next phase of transformation occurred when Disney decided to rebrand the hotel as Paradise Pier Hotel. This decision aligned with Disney’s broader vision for the Disneyland Resort.

While the structural changes were limited, the hotel underwent a significant cosmetic makeover. Its exterior was painted to complement the color scheme of Paradise Pier, and wave-shaped crenellations adorned the rooftop, creating an illusion of seaside charm. This transformation was Disney’s attempt to seamlessly integrate the hotel into the Paradise Pier theme of Disney’s California Adventure Park.

Looking Beyond Paradise Pier: The Shift to Pixar Place

In 2018, Disneyland Resort rebranded Paradise Pier as Pixar Pier, a thematic area dedicated to celebrating the beloved characters and stories from Pixar Animation Studios. As a part of this transition, it became evident that the hotel formally known as the Disneyland Pacific Hotel could no longer maintain its Paradise Pier theme.

With Pixar Pier in full swing and two successful Pixar-themed hotels (Toy Story Hotels in Shanghai Disneyland and Tokyo Disneyland), Disney decided to embark on a new venture—a hotel that would celebrate the vast world of Pixar. The result is Pixar Place Hotel, a 15-story tower that embraces the characters and stories from multiple Pixar movies and shorts. This fully Pixar-themed hotel is a first of its kind in the United States.

The Future of Pixar Place and Disneyland Resort

As we look ahead to the future, the Disneyland Resort continues to evolve. The recent news of a proposed $1.9 billion expansion as part of the Disneyland Forward project indicates that the area surrounding Pixar Place is expected to see further changes. Disneyland’s rich history and innovative spirit continue to shape its destiny.

In conclusion, the history of the Pixar Place Hotel is a testament to the ever-changing landscape of Disneyland Resort. From its humble beginnings as the Disneyland Hotel to its transformation into the fully Pixar-themed Pixar Place Hotel, this establishment has undergone several iterations. As Disneyland Resort continues to grow and adapt, we can only imagine what exciting developments lie ahead for this iconic destination.

If you want to hear more stories about the History of the Pixar Place hotel, check our special edition of Disney Unpacked over on YouTube.

Stay tuned for more updates and developments as we continue to explore the fascinating world of Disney, one story at a time.

History

From Birthday Wishes to Toontown Dreams: How Toontown Came to Be

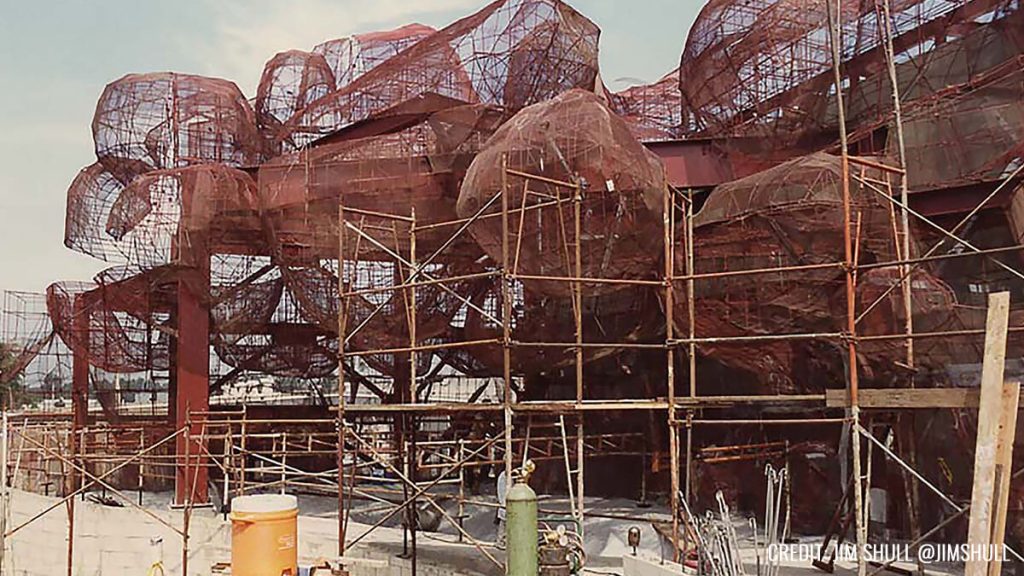

In the latest release of Episode 4 of Disney Unpacked, Len and I return, joined as always by Disney Imagineering legend, Jim Shull. This two-part episode covers all things Mickey’s Birthday Land and how it ultimately led to the inspiration behind Disneyland’s fan-favorite land, “Toontown”. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves here. It all starts in the early days at Disneyland.

Early Challenges in Meeting Mickey

Picture this: it’s the late 1970s and early 1980s, and you’re at Disneyland. You want to meet the one and only Mickey Mouse, but there’s no clear way to make it happen. You rely on Character Guides, those daily printed sheets that point you in Mickey’s general direction. But let’s be honest, it was like finding a needle in a haystack. Sometimes, you got lucky; other times, not so much.

Mickey’s Birthdayland: A Birthday Wish that Came True

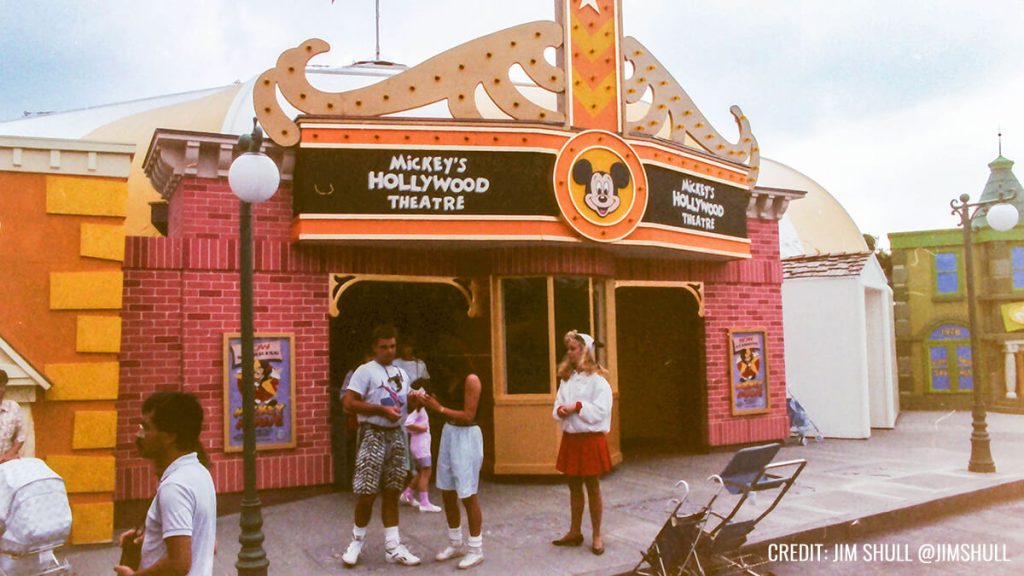

Fast forward to the late 1980s. Disney World faced a big challenge. The Disney-MGM Studios Theme Park was under construction, with the company’s marketing machine in full swing, hyping up the opening of Walt Disney World’s third theme park, MGM Studios, in the Spring of 1989. This extensive marketing meant that many people were opting to postpone their family’s next trip to Walt Disney World until the following year. Walt Disney World needed something compelling to motivate guests to visit Florida in 1988, the year before Disney MGM Studios opened.

Enter stage left, Mickey’s Birthdayland. For the first time ever, an entire land was dedicated to a single character – and not just any character, but the mouse who started it all. Meeting Mickey was no longer a game of chance; it was practically guaranteed.

The Birth of Birthdayland: Creative Brilliance Meets Practicality

In this episode, we dissect the birth of Mickey’s Birthdayland, an initiative that went beyond celebrating a birthday. It was a calculated move, driven by guest feedback and a need to address issues dating back to 1971. Imagineers faced the monumental task of designing an experience that honored Mickey while efficiently managing the crowds. This required the perfect blend of creative flair and logistical prowess – a hallmark of Disney’s approach to theme park design.

Evolution: From Birthdayland to Toontown

The success of Mickey’s Birthdayland was a real game-changer, setting the stage for the birth of Toontown – an entire land that elevated character-centric areas to monumental new heights. Toontown wasn’t merely a spot to meet characters; it was an immersive experience that brought Disney animation to life. In the episode, we explore its innovative designs, playful architecture, and how every nook and cranny tells a story.

Impact on Disney Parks and Guests

Mickey’s Birthdayland and Toontown didn’t just reshape the physical landscape of Disney parks; they transformed the very essence of the guest experience. These lands introduced groundbreaking ways for visitors to connect with their beloved characters, making their Disney vacations even more unforgettable.

Beyond Attractions: A Cultural Influence

But the influence of these lands goes beyond mere attractions. Our episode delves into how Mickey’s Birthdayland and Toontown left an indelible mark on Disney’s culture, reflecting the company’s relentless dedication to innovation and guest satisfaction. It’s a journey into how a single idea can grow into a cherished cornerstone of the Disney Park experience.

Unwrapping the Full Story of Mickey’s Birthdayland

Our two-part episode of Disney Unpacked is available for your viewing pleasure on our Patreon page. And for those seeking a quicker Disney fix, we’ve got a condensed version waiting for you on our YouTube channel. Thank you for being a part of our Disney Unpacked community. Stay tuned for more episodes as we continue to “Unpack” the fascinating world of Disney, one story at a time.

-

News & Press Releases11 months ago

News & Press Releases11 months agoDisney Will Bring D23: The Ultimate Disney Fan Event to Anaheim, California in August 2024

-

History6 months ago

History6 months agoFrom Birthday Wishes to Toontown Dreams: How Toontown Came to Be

-

History6 months ago

History6 months agoUnpacking the History of the Pixar Place Hotel

-

History6 months ago

History6 months agoThe Evolution and History of Mickey’s ToonTown

-

News & Press Releases5 months ago

News & Press Releases5 months agoNew Updates and Exclusive Content from Jim Hill Media: Disney, Universal, and More

-

Film & Movies3 months ago

Film & Movies3 months agoHow Disney’s “Bambi” led to the creation of Smokey Bear

-

Merchandise4 months ago

Merchandise4 months agoIntroducing “I Want That Too” – The Ultimate Disney Merchandise Podcast