Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment

Looking back on the Disney-MGM Studio Backlot project — Part 3

JHM guest writer Todd James Pierce continues his 4-part series about the 40-acre entertainment district that the Walt Disney Company once wanted to build in Burbank. Today’s installment actually takes JHM readers inside of this proposed park

Picking up where we left off yesterday …

Despite the two MCA lawsuits, Disney continued to develop plans for the Disney-MGM Studio Backlot in Burbank.

At the helm of the Disney project were two Imagineers: a young Joe Rohde (then 32-years-old) and Rick Rothschild. Their mission was to seamlessly integrate a Disney-style park into a downtown urban environment. To accomplish this, Rohde and Rothchild spent hours on the top floors of nearby buildings (also in the exterior glass elevator at the Burbank Holiday Inn) to get a bird’s eye view of the land earmarked for the Disney project. At that time, the land was little more than a weedy lot, bordered by the Golden State Freeway and the Burbank Civic Center. Specifically the two Imagineers wanted to observe how traffic and pedestrians moved around the 40-acre parcel. Eventually they designed a park layout in which all of the retail stores were stationed along the outside border of the property to accommodate casual shoppers. “All the crazy stuff will be in the middle,” Rhode explained.

Taking a cue from the new Pleasure Island development at Walt Disney World, the Imagineers solidified the back-story and overall theme for the Burbank property. The back-story involved a gold rush town and a movie studio. But the back-story is difficult to explain without first talking about the strange—and now mostly forgotten—original back-story for Pleasure Island.

As you recall, Pleasure Island and the Disney-MGM Studio Backlot were under development at the same time. Both were heavily themed leisure zones that would include—to some extent—shopping, restaurants, entertainment venues, and nightclubs. To explain the strange collection of buildings that would become Pleasure Island, Imagineers invented the story of Merriweather Adam Pleasure. Or (to point out the pun) Mr. M. A. Pleasure.

In the early 1900s, Mr. Pleasure docked his Mississippi steamboat in Lake Buena Vista. So impressed by the local beauty, he and his family decided to stay and open a sail-making factory and a canvas plant. Each required its own industrial building. After early success, the family built a southern mansion, a yacht house, and “The Adventurers Club,” where Mr. Pleasure kept a lifetime of travel souvenirs. The family also constructed buildings for Mr. Pleasure’s other interests, such as exotic plants and the manufacture of fireworks. But in 1941, while traveling to Antarctica, Mr. Pleasure and his wife died in an unexpected storm. In their absence, the sail-making factory and yacht town wasted away until it was rediscovered by the fine folks at Disney World, who turned it in to an nighttime entertainment center—by adapting the yacht club, the Mississippi steamboat, and the various manufacturing and industrial buildings into a collection of elaborately themed clubs.

Though the surface details are different for the Disney-MGM Studio Backlot story, the underlying impulse is the same: to explain to guests that the seemingly unconnected architectural styles in the Backlot did in fact form a unified fantasy world. The story went like this:

In the late 1890s, a few residents of Burbank—or whatever Burbank was called in the 1890s—discovered gold. Shortly after thereafter, a western town developed. And some twenty or thirty years later, long after all of the gold was mined, the locals considered the best way to invest their grand fortune. Their answer: to make movies. And to make these movies, they created a backlot complete with a Parisian lane, a Spanish street, and a California boardwalk. Somewhat later they also built a TV and radio studio. Just like Mr. Pleasure’s sail factory, the old Burbank studio would go out of business in the middle of the 20th century—only to be rediscovered by Disney, who would transform the area into a theme-park-slash-shopping-district. For guests, the back-story would explain the jumble of architectural styles and the unusual use of many buildings: the western gold rush town, the American-style restaurant housed in a Parisian apartment building, the souvenir shop shoehorned into a Spanish hut, and the California boardwalk complete with a mock “Ocean” and a few carnival rides.

For the press, Rothchild spelled it out simply: The Disney-MGM Studio Backlot would be a mythical “studio backlot, where great movies of the past were filmed.” The shops, restaurants, nightclubs, and ride buildings would be tucked into old back lot facades. “That way,” he continued, “we could incorporate the variety of themes, make streets interchangeable.”

In addition to the attractions earlier announced, WDI now revealed plans for other rides and restaurants:

* Two new high-end restaurants: The first would be housed in a boat caught halfway over the top of the 60-foot waterfall—with water cascading around the vessel. While waiting for a table, guests could look out underwater windows into the Burbank Ocean to see lobster traps filled with miniature cattle—tiny herds of black-and-white plastic cows. (The miniature “aquatic beef” would supposedly be included on the menu.) The second restaurant would be a formal dining affair at the top of the Hollywood Fantasy Hotel. This elegant room would feature a planetarium projection system to create a star-scape across the domed ceiling. Constellations would change with the seasons.

* A children’s area—modeled after a sound stage—where parents could reserve private banquet rooms to have Mickey Mouse host their child’s birthday party.

* A 10-screen multiplex, a roller skating rink an ice skating rink, and venue for live theater.

* An enormous Ferris wheel that would dip down into the manmade lake, as part of the California beach boardwalk.

Imagineers were also developing a new simulator attraction—similar in style to the Star Tours attraction recently opened at Disneyland—though the storyline for this attraction was never released.

As these plans came together—and as Eisner saw potential profit in more urban parks—Disney announced that they were looking to franchise this concept. Though of course, future urban parks would not include the TV studio and the animation complex, as those would be unique to the Burbank Backlot experience. Specifically, Disney announced that it was pursuing developments in Chicago, Dallas, Philadelphia, and San Antonio—each with a unique theme derived from the area’s local history. “We’ll be doing more of these,” Rothschild explained to a local reporter, “and we will fit them to the needs of the community.”

But while Disney was developing a full-site plan for the Burbank property—and while Eisner was trying to sell this “themed-space” concept to other cities—Burbank citizens began to receive pamphlets that described the mess Disney’s Backlot would cause for local residents.

With glossy photos and color illustrations, the first pamphlet claimed that the Disney development “will turn virtually all of downtown Burbank into a massive tourist complex and require a tax subsidy of over one-hundred million dollars.” It also claimed that the secret deal was finalized “after less than 30 minutes of council discussion” with “no competitive bidding.”

The cover of the second pamphlet featured a photo of the Disneyland castle with the caption: “It’s a nice place to visit.” The interior included images of dingy hotels, cheap liquor stores, and tacky tourist shops beside a single line of text: “But you wouldn’t want to live there.”

A third pamphlet emphasized the environmental damage the Backlot would cause to the city.

A fourth reiterated the major points made in the first three mailings, while emphasizing the cost of the Disney project to taxpayers.

The fliers were sent by a new political group known as the “Friends of Burbank,” who listed as their only address a private mail-drop. From the start Burbank officials felt they knew who was behind the attack: “Somebody, and I assume it’s MCA,” Councilwoman Mary Lou Howard said, “is spending a lot of money to get their point across.”

Two weeks after the first brochure was mailed, city officials were able to prove that, in fact, MCA was behind the “Friends of Burbank” campaign. “What the mailers failed to mention, however,” one local newspaper announced, “was the one almost certain result of the Disney project—tough competition for MCA’s own Universal City complex.”

Shamed into admitting fault, an MCA attorney begrudgingly offered a statement to the press: “Obviously, we would have preferred to have a full discussion of the issues, but since Burbank will not do it, we decided to get the word out any way we could. We knew there would be consequences, but we are prepared to accept them.”

The mailings, it was revealed, cost MCA roughly $20,000 and went out to 43,000 Burbank residents.

Clearly gloating, Michael Eisner issued the statement for Disney: “This activity is totally uncharacteristic of any major American corporation. Therefore, we’re at a loss for words.”

Though the City of Burbank had originally contacted Eisner with the hopes that Disney would somehow help save a local mall project, they now found themselves in the middle of a bitter fight between two corporate rivals. One city attorney, still not grasping the overall context, told the press that these ongoing lawsuits were an “obvious attempt by a multinational corporate conglomerate to dash the dreams of a city that wants a retail shopping center.”

Come back tomorrow for the conclusion of our story.

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment

Disney and Macy’s 90-Year Thanksgiving Day Parade Partnership: From Mickey’s First Balloon to Minnie’s Big Debut

Now, folks, if you’re like me, Thanksgiving just wouldn’t be the same without a coffee, a cozy seat, and Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade on the TV. And if you’re really like me, you’re watching for one thing: Disney balloons floating down 34th Street. Ever wondered how Mickey, Donald, and soon Minnie Mouse found their way into this beloved New York tradition? Well, grab your popcorn because we’re diving into nearly 90 years of Disney’s partnership with Macy’s.

The Very First Parade and the Early Days of Balloons

The Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade goes way back to 1924, but if you can believe it, balloons weren’t part of the festivities until 1927. That first lineup included Felix the Cat, a dragon, and a toy soldier, all towering above the crowds. Back then, Macy’s had a pretty wild idea to end the parade: they would let the balloons drift off into the sky, free as birds. But this wasn’t just Macy’s feeling generous. Each balloon had a message attached, offering a $100 reward (about $1,800 in today’s dollars) for anyone who returned it to the flagship store on 34th Street.

And here’s where it gets interesting. This tradition carried on for a few years, right up until 1932, when Felix the Cat almost took down a plane flying over New York City! Imagine that—you’re flying into LaGuardia, and suddenly, there’s a 60-foot balloon drifting toward your wing. Needless to say, that was the end of Macy’s “fly away” stunt, and from then on, the balloons have stayed firmly grounded after the parade ends.

1934: Mickey Mouse Floats In, and Disney Joins the Parade

It was 1934 when Mickey Mouse finally made his grand debut in the Macy’s parade. Rumor has it Walt Disney himself collaborated with Macy’s on the design, and by today’s standards, that first Mickey balloon was a bit of a rough cut. This early Mickey had a hotdog-shaped body, and those oversized ears gave him a slightly lopsided look. But no one seemed to mind. Mickey was there, larger than life, floating down the streets of New York, and the crowd loved him.

Mickey wasn’t alone that year. He was joined by Pluto, Horace Horsecollar, and even the Big Bad Wolf and Practical Pig from The Three Little Pigs, making it a full Disney lineup for the first time. Back then, Disney wasn’t yet the entertainment powerhouse we know today, so for Walt, getting these characters in the parade meant making a deal. Macy’s required its star logo to be featured on each Disney balloon—a small concession that set the stage for Disney’s long-standing presence in the parade.

Duck Joins and Towers Over Mickey

A year later, in 1935, Macy’s introduced Donald Duck to the lineup, and here’s where things got interesting. Mickey may have been the first Disney character to float through the parade, but Donald made a huge splash—literally. His balloon was an enormous 60 feet tall and 65 feet long, towering over Mickey’s 40-foot frame. Donald quickly became a fan favorite, appearing in the lineup for several years before being retired.

Fast-forward a few decades, and Donald was back for a special appearance in 1984 to celebrate his 50th birthday. Macy’s dug the balloon out of storage, re-inflated it, and sent Donald down 34th Street once again, bringing a bit of nostalgia to the holiday crowd.

A Somber Parade in 2001

Now, one of my most memorable trips to the parade was in 2001, just weeks after the 9/11 attacks. Nancy and I, along with our friends, headed down to New York, and the mood was something I’ll never forget. We watched the start of the parade from Central Park West, but before that, we went to the Museum of Natural History the night before to see the balloons being inflated. They were covered in massive cargo nets, with sandbags holding them down. It’s surreal to see these enormous balloons anchored down before they’re set free.

That year, security was intense, with police lining the streets, and then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani rode on the Big Apple float to roaring applause. People cheered his name, waving and shouting as he passed. It felt like the entire city had turned out to show their resilience. Even amidst all the heightened security and tension, seeing those balloons—brought a bit of joy back to the city.

Balloon Prep: From New Jersey’s MetLife Stadium to California’s D23 Expo

Each year before the parade, Macy’s holds a rehearsal event known as Balloon Fest at MetLife Stadium in New Jersey. This is where handlers get their first crack at guiding the balloons, practicing with their parade masters, and learning the ropes—literally. It’s an entire production unto itself, with dozens of people rehearsing to make sure these enormous inflatables glide smoothly down the streets of New York on parade day.

In 2015, Macy’s took the balloon show on the road, bringing their Buzz Lightyear balloon out to California for the D23 Expo. I was lucky enough to be there, and watching Buzz get inflated piece by piece in the Anaheim Convention Center parking lot was something to behold. Each section was filled with helium in stages, and when they got around to Buzz’s lower half, well, there were more than a few gas-related jokes from the crowd.

These balloons seem to have a personality all their own, and seeing one like Buzz come to life up close—even outside of New York—had all the excitement and anticipation of the real deal.

Mickey’s Comeback as a Bandleader and Sailor Mickey

After a long hiatus, Mickey Mouse made his return to the Macy’s parade in 2000, this time sporting a new bandleader outfit. Nine years later, in 2009, Sailor Mickey joined the lineup, promoting Disney Cruise Line with a nautical twist. Over the past two decades, Disney has continued to enchant parade-goers with characters like Buzz Lightyear in 2008 and Olaf from Frozen in 2017. These balloons keep Disney’s iconic characters front and center, drawing in both longtime fans and new viewers.

But ever wonder what happens to the balloons after they reach the end of 34th Street? They don’t just disappear. Each balloon is carefully deflated, rolled up like a massive piece of laundry, and packed into storage bins. From there, they’re carted back through the Lincoln Tunnel to Macy’s Parade Studio in New Jersey, where they await their next flight.

Macy’s Disney Celebration at Hollywood Studios

In 1992, Macy’s took the spirit of the parade down to Disney-MGM Studios in Orlando. After that year’s parade, several balloons—including Santa Goofy, Kermit the Frog, and Betty Boop—were transported to Hollywood Studios, re-inflated, and anchored along New York Street as part of a holiday display. Visitors could walk through this “Macy’s New York Christmas” setup and see the balloons up close, right in the middle of the park. While this display only ran for one season, it paved the way for the Osborne Family Spectacle of Dancing Lights, which became a holiday staple at the park for years to come.

Minnie Mouse’s Long-Awaited Debut in 2024

This year, Minnie Mouse will finally join the parade, making her long-overdue debut. Macy’s is rolling out the red carpet for Minnie’s arrival with special pop-up shops across the country, where fans can find exclusive Minnie ears, blown-glass ornaments, T-shirts, and more to celebrate her first appearance in the Thanksgiving Day Parade.

For those lucky enough to catch the parade this year, you’ll see Minnie take her first float down 34th Street, decked out in her iconic red bow and polka-dot dress. Macy’s and Disney are also unveiling a new Disney Cruise Line float honoring all eight ships, including the latest, the Disney Treasure.

As always, I’ll be watching from my favorite chair, coffee in hand, as Minnie makes her grand entrance. The 98th annual Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade airs live on NBC, and it’s a tradition you won’t want to miss—whether you’re on 34th Street or tuning in from home.

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment

Disney’s Forgotten Halloween Event: The Original Little Monsters on Main Street

When most Disney fans think of Halloween in the parks, they immediately picture Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party at Walt Disney World or the Oogie Boogie Bash at Disneyland Resort. But before those events took over as the must-attend spooky celebrations, there was a little-known event at Disneyland called Little Monsters on Main Street. And its origins? Well, they go all the way back to the 1980s, during a time when America was gripped by fear—the Satanic Panic.

You see, back in the mid-1980s, parents were terrified that Halloween had become dangerous. Urban legends about drug-laced candy or razor blades hidden in apples were widespread, and many parents felt they couldn’t let their kids out of sight for even a moment. Halloween, which was once a carefree evening of trick-or-treating in the neighborhood, had suddenly become a night filled with anxiety.

This is where Disneyland’s Little Monsters on Main Street came in.

The Origins of Little Monsters on Main Street

Back in 1989, the Disneyland Community Action Team—later known as the VoluntEARS—decided to create a safe, nostalgic Halloween experience for Cast Members and their families. Many schools in the Anaheim area were struggling to provide basic school supplies to students, and the VoluntEARS saw an opportunity to combine a safe Halloween with a charitable cause. Thus, Little Monsters on Main Street was born.

This event was not open to the general public. Only Disneyland Cast Members could purchase tickets, which were initially priced at just $5 each. Cast Members could bring their kids—but only as many as were listed as dependents with HR. And even then, the park put a cap on attendance: the first event was limited to just 1,000 children.

A Unique Halloween Experience

Little Monsters on Main Street wasn’t just another Halloween party. It was designed to give kids a safe, fun environment to enjoy trick-or-treating, much like the good old days. On Halloween night in 1989, kids in costume wandered through Disneyland with their pillowcases, visiting 20 different trick-or-treat stations. They also had the chance to ride a few of their favorite Fantasyland attractions, all after the park had closed to the general public.

The event was run entirely by the VoluntEARS—about 200 of them—who built and set up all the trick-or-treat stations themselves. They arrived at Disneyland before the park closed and, as soon as the last guest exited, they began setting up stations across Main Street, Adventureland, Frontierland, Fantasyland, and Tomorrowland. The event ran from 7:30 to 9:30 p.m., and by the time the last pillowcase-wielding kid left, the VoluntEARS cleaned everything up, making sure the park was ready for the next day’s operations.

It wasn’t just candy and rides, though. The event featured unique entertainment, like a Masquerade Parade down Main Street, U.S.A., where kids could show off their costumes. And get this—Disneyland even rigged up a Cast Member dressed as a witch to fly from the top of the Matterhorn to Frontierland on the same wire that Tinker Bell uses during the fireworks. Talk about a magical Halloween experience!

The Haunted Mansion “Tip-Toe” Tour

Perhaps one of the most memorable parts of Little Monsters on Main Street was the special “tip-toe tour” of the Haunted Mansion. Now, Disneyland’s Haunted Mansion can be a pretty scary attraction for younger kids, so during this event, Disney left the doors to the Stretching Room and Portrait Gallery wide open. This allowed kids to walk through and peek at the Haunted Mansion’s spooky interiors without actually having to board the Doom Buggies. For those brave enough to ride, they could, of course, take the full trip through the Haunted Mansion—or they could take the “chicken exit” and leave, no harm done.

Growing Success and a Bigger Event

Thanks to the event’s early success, Little Monsters on Main Street grew in size. By 1991, the attendance cap had been raised to 2,000 kids, and Disneyland added more activities like magic shows and hayrides. They also extended the event’s hours, allowing kids to enjoy the festivities until 10:30 p.m.

In 2002, the event moved over to Disney California Adventure, where it could accommodate even more kids—up to 5,000 in its later years. The name was also shortened to just Little Monsters, since it was no longer held on Main Street. This safe, family-friendly Halloween event continued for several more years, with the last mention of Little Monsters appearing in the Disneyland employee newsletter in 2008. Though some Cast Members recall the event continuing until 2012, it eventually made way for Disney’s more public-facing Halloween events.

From Little Monsters to Mickey’s Not-So-Scary and Oogie Boogie Bash

Starting in the early 2000s, Disney began realizing the potential of Halloween-themed after-hours events for the general public. These early versions of Mickey’s Halloween Party and Mickey’s Halloween Treat eventually evolved into today’s Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party and Oogie Boogie Bash. Unfortunately, this also marked the end of the intimate, Cast Member-exclusive Little Monsters event, but it paved the way for the large-scale Halloween celebrations we know and love today.

While it’s bittersweet to see Little Monsters on Main Street fade into Disney history, its legacy lives on through these modern Halloween parties. And even though Cast Members now receive discounted tickets to Mickey’s Not-So-Scary and Oogie Boogie Bash, the special charm of an event created specifically for Disney’s employees and their families remains something worth remembering.

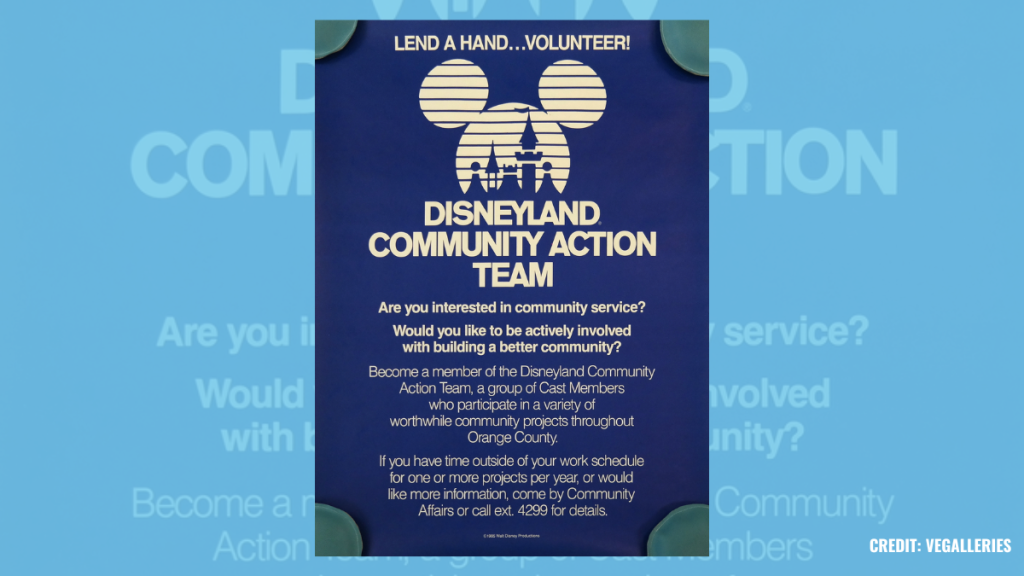

The Merch: A Piece of Little Monsters History

For Disney collectors, the exclusive merchandise created for Little Monsters on Main Street is still out there. You can find pins, name tags, and themed pillowcases on sites like eBay. One of the coolest collectibles is a 1997 cloisonné pin set featuring Huey, Dewey, and Louie dressed as characters from Hercules. Other sets paid tribute to the Main Street Electrical Parade and Pocahontas, while the pillowcases were uniquely designed for each year of the event.

While Little Monsters on Main Street may be gone, it’s a fascinating piece of Disneyland history that played a huge role in shaping the Halloween celebrations we enjoy at Disney parks today.

Want to hear more behind-the-scenes stories like this? Be sure to check out I Want That Too, where Lauren and I dive deep into the history behind Disney’s most beloved attractions, events, and of course, merchandise!

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment

The Story of Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party: From One Night to a Halloween Family Tradition

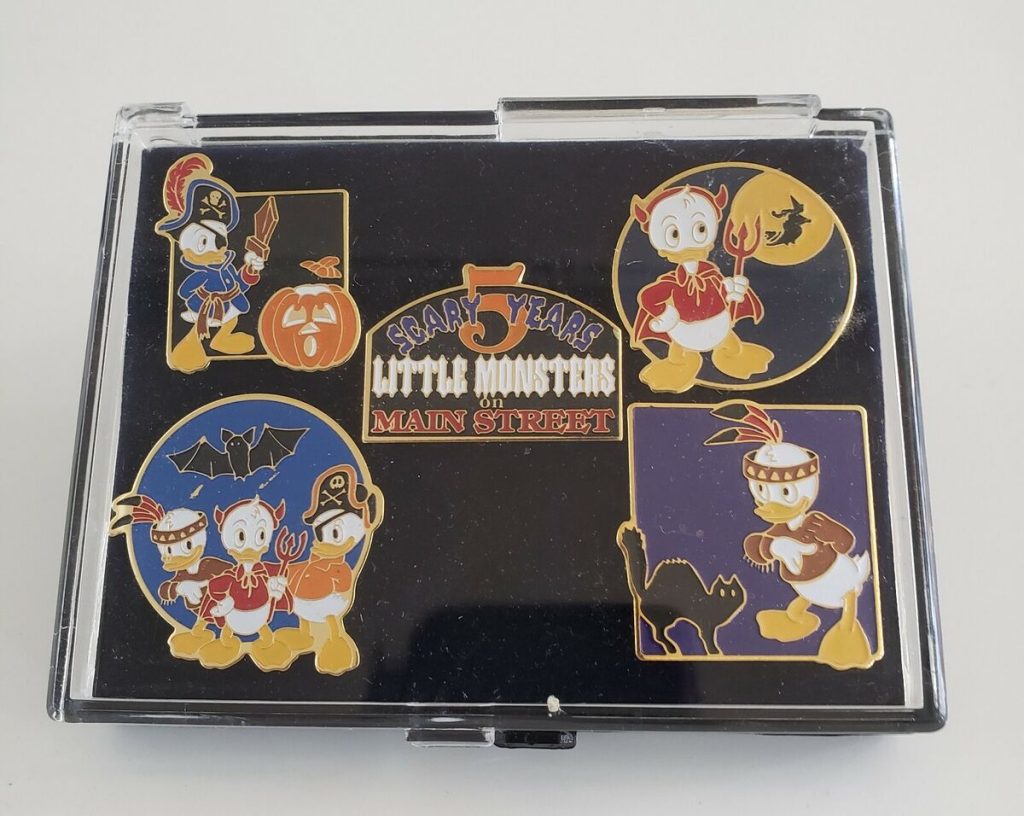

The spooky season is already in full swing at Disney parks on both coasts. On August 9th, the first of 38 Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party (MNSSHP) nights for 2024 kicked off at Florida’s Magic Kingdom. Meanwhile, over at Disney California Adventure, the Oogie Boogie Bash began on August 23rd and is completely sold out across its 27 dates this year.

Looking back, it’s incredible to think about how these Halloween-themed events have grown. But for Disney, the idea of charging guests for Halloween fun wasn’t always a given. In fact, when the very first Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party debuted on October 31, 1995, it was a modest one-night-only affair. Compare that to the near month-long festivities we see today, and it’s clear that Disney’s approach to Halloween has evolved considerably.

A Not-So-Scary Beginning

I was fortunate enough to attend that very first MNSSHP back in 1995, along with my then 18-month-old daughter Alice and her mom, Michelle. Tickets were a mere $16.95 (I know, can you imagine?), and we pushed Alice around in her sturdy Emmaljunga stroller—Swedish-built and about the size of a small car. Cast Members, charmed by her cuteness, absolutely loaded us up with candy. By the end of the night, we had about 30 pounds of fun-sized candy bars, making that push up to the monorail a bit more challenging.

This Halloween event was Disney’s response to the growing popularity of Universal Studios Florida’s own Halloween hard ticket event, which started in 1991 as “Fright Nights” before being rebranded as “Halloween Horror Nights” the following year. Universal’s gamble on a horror-themed experience helped salvage what had been a shaky opening for their park, and by 1993, Halloween Horror Nights was a seven-night event, with ticket prices climbing as high as $35. Universal had stumbled upon a goldmine, and Disney took notice.

A Different Approach

Now, here’s where Disney’s unique strategy comes into play. While Universal embraced the gory, scare-filled world of horror, Disney knew that wasn’t their brand. Instead of competing directly with blood and jump-scares, Disney leaned into what they did best: creating magical, family-friendly experiences.

Thus, Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party was born. The focus was on fun and whimsy, not fear. Families could bring their small children without worrying about them being terrified by a chainsaw-wielding maniac around the next corner. This event wasn’t just a Halloween party—it was an extension of the Disney magic that guests had come to expect from the parks.

Disney had some experience with seasonal after-hours events, most notably Mickey’s Very Merry Christmas Party, which had started in 1983. But the Halloween party was different, as the Magic Kingdom wasn’t yet decked out in Halloween decor the way it is today. Disney had to create a spooky (but not too spooky) atmosphere using temporary props, fog machines, and, of course, lots of candy.

A key addition to that first event? The debut of the Headless Horseman, who made his eerie appearance in Liberty Square, riding a massive black Percheron. It wasn’t as elaborate as the Boo-to-You Parade we see today, but it marked the beginning of a beloved Disney Halloween tradition.

A Modest Start but a Big Future

That first MNSSHP in 1995 was seen as a trial run. As Disney World spokesman Greg Albrecht told the Orlando Sentinel, “If it’s successful, we’ll do it again.” And while attendance was sparse that night, there was clearly potential. By 1997, the event expanded to two nights, and by 1999, Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party had grown into a multi-night celebration with a full-fledged parade. Today, in 2024, it’s a staple of the fall season at Walt Disney World, offering 38 nights of trick-or-treating, character meet-and-greets, and special entertainment.

Universal’s Influence

It’s interesting to reflect on how Disney’s Halloween event might never have existed without the competition from Universal. Just as “The Wizarding World of Harry Potter” forced Disney to step up their game with “Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge,” Universal’s success with Halloween Horror Nights likely spurred Disney into action with MNSSHP. The friendly rivalry between the two parks has continually pushed both to offer more to their guests, and we’re all better off because of it.

So the next time you find yourself trick-or-treating through the Magic Kingdom, watching the Headless Horseman gallop by, or marveling at the seasonal fireworks, take a moment to appreciate how this delightful tradition came to be—all thanks to a little competition and Disney’s commitment to creating not-so-scary magic.

For more Disney history and behind-the-scenes stories, check out the latest episodes of the I Want That Too podcast on the Jim Hill Media network.

-

History10 months ago

History10 months agoThe Evolution and History of Mickey’s ToonTown

-

History11 months ago

History11 months agoUnpacking the History of the Pixar Place Hotel

-

History11 months ago

History11 months agoFrom Birthday Wishes to Toontown Dreams: How Toontown Came to Be

-

Film & Movies8 months ago

Film & Movies8 months agoHow Disney’s “Bambi” led to the creation of Smokey Bear

-

News & Press Releases10 months ago

News & Press Releases10 months agoNew Updates and Exclusive Content from Jim Hill Media: Disney, Universal, and More

-

Merchandise8 months ago

Merchandise8 months agoIntroducing “I Want That Too” – The Ultimate Disney Merchandise Podcast

-

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment3 months ago

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment3 months agoDisney’s Forgotten Halloween Event: The Original Little Monsters on Main Street

-

Film & Movies3 months ago

Film & Movies3 months agoHow “An American Tail” Led to Disney’s “Hocus Pocus”