Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment

Ruminations

It’s another trip back to the storage locker and another classic animation book review from Roger’s keyboard! Something old and something new…

This is the second of two parts adapted from two articles that appeared in Issues Four and Five of YARF! way back in May and then July of 1990. Originally done with an absolutely ancient version of Aldus Pagemaker on a Macintosh SE, they were an interesting look into the printed page. This time out, Disney characters are the focus.

Last time, we looked at a book about the Warner Brothers Merrie Melodies and Looney Tunes. This time we’ll do the flip side with the “Encyclopedia of Walt Disney’s Animated Characters” by John Grant (Published by Harper and Row, 1987. Suggested retail price $35.00) It would be fair to say that Disney enjoyed a wealth of characters because of both features and shorts, where as Warner was limited to shorts.

The introduction to this book sets the tone to explain why Disney characters were (and are) different from those of other studios:

“Until a character becomes a personality it cannot be believed. Without personality, the character may do funny or interesting things, but unless people are able to identify themselves with the character, it’s actions will seem unreal. And without personality, a story cannot ring true to the audience.”

Those words of Walt Disney describe why his studio became to the most successful animation company of it’s day. We think of these characters as real, and in that, the Disney animators have succeeded. This doesn’t mean that Bugs Bunny or Tom & Jerry aren’t good characters, but the Disney staff seemed to have the ability to bring it’s characters to life in ways that were above the other studios. We see Disney characters as real personalities with real emotions in real life situations. Looking at shorts from other studios, that wasn’t always possible or something necessary. A personal example comes in the Disney feature, “Lady & The Tramp”. The scenes early one with lady as very young puppy derive from reality. Having been through the same situations in my own life (as my mother bred cocker spaniels for the dog show world once upon a time), I laugh every time I see these scenes because I can identify with the real quality of them. That’s the Disney secret!

This book comes as close to being complete (for the publication dates) as any I have found about Disney characters. It is broken down by short subjects and animated features. It is (was) current up to 1985’s “Wuzzles” and “Gummi Bears” for shorts and up to 1986’s “The Great Mouse Detective” for features. The section on shorts id sorted by characters rather than by subject title, and they are in chronological order of appearance. That list begins with the “Newman Laugh-O-Grams” which Walt produced for a local cinema in Kansas City in 1921. The running times were less than a minute. The first character listing is for “Julius the Cat” from the “Alice” series of shorts. They featured a live action young girl (Alice) interacting with the animation. Julius is a Felix look-alike and never appeared in anything other than the “Alice” shorts. The listing also includes a filmography with all possible appearances.

Here is a typical character entry — for the character “Bootle Beetle”:

BOOTLE BEETLE:

If they were small, and especially if they were insects, they inevitably became foes of Donald Duck. Bootle Beetle, who first appeared in the short “Bootle Beetle” (1947), carried on the great tradition. Voiced by Dink Trout, the little coleopteran got his name thank to Jack Hannah, who directed the original short. Hannah’s wife knew of a racehorse in Pomona called “Beetle Bootle”, and he merely switched the two names around.

Of the three shorts he made, the first, “Bootle Beetle” is probably the best known. The elderly Bootle is telling the younger Ezra Beetle of the ills of running away and recalls the story of his own youth, which seems mainly to have occupied chases between himself and Donald. Nowadays, although Bootle is an old man, so is Donald — and elderly Duck is still chasing him. He is still reminiscing in “Sea Salts” (1949), about the time he and Donald were shipwrecked. Of their surviving provision Donald always seems to get the best ration but somehow this does no disrupt the friendship of the two.

His final outing was in the short, “The Greener Yard” (1949). Yet again he is reminiscing to Ezra. Once upon a time, he tells the little beetle as the two of them survey Donald’s yard over the fence, he took the risk of plundering that yard for food. However, all that happened was that he was chased by Donald and nearly lost his life. He tells the story so dramatically (with flashbacks to the real action) that young Ezra is content to stick with the meal he has in front of him rather than trying for the delights on the other side of the fence.

Bootle Beetle’s career never got off the ground. Somehow he was not really enough of a personality to make it to the top — although, in contradiction to that, it should be pointed out that Buzz-Buzz who has no personality except for a venomous desire to use his sting, did much better for himself.

Filmography —

“Bootle Beetle”, August 1947

“Sea Salts”, 1949

“The Greener Yard” 1949Ezra Beetle appeared only in “Bootle Beetle” and in “The Greener Yard”.

The entry is accompanied by two color views for both Bootle Beetle and Ezra Beetle. A major character such as Goofy has an appropriately larger entry consistent with all of his appearances. Each Entry give all the information about the character, and if known, a credit for the voice(s) which contributed to it.

The section on features is a bit more involved but again well done. Once more, it is arranged in chronological order but this time by title rather than by character. Beginning with “Snow White” (released December 21, 1937), it covers the features in order. Some of the entries may seem out of place here as you don’t think of them as features. But they are listed that way because that’s how Disney released them to the theaters. A good example is the World War II feature, “Victory Through Airpower”, (1943). While it was a promotional film for escalating the war effort through increased reliance on air power, it does contain animation. And it is all detailed in the entry for the title. There are also other entries for live action films that included animation in their productions.

Usually an entry is headlined by the title. Then the characters are listed, followed by the credits (which include the voices). After the credits, the date of the release is given as well as the total running time of the film. Then a section with notes on the film and it’s production is presented. A synopsis of the story is offered, and then the listing for the characters. Views of the character accompany the list. Due to space considerations in YARF!, a full example of a feature reference would be too much. But here is a condensed version to offer you a sample of the information that is found in a typical listing.

“Melody Time”

Characters:Little Toot section:

Little Toot, Big Toot

Voices/Musicians: The Andrews Sisters

Release Date: May 27, 1948

Running Time: 7.5 minutesLittle Toot Section:

As the Andrews Sisters tunefully tell us,

“Little Toot was just a tugboat,

A happy harbor tug.

He came from a line tugboats fine and brave.

But it seems that Little Toot,

Simply didn’t give a hoot.

Though he tried to be good he never could behave.”In other words, like many another small Disney hero, “Little Toot”, a New York harbor tug, is the “naughty one”. Indeed, he is an extremely mischievous little boat. We see him indulging in all sorts of minor misdemeanors before one day he goes too far, peppering the portholes of a liner with blasts of dense smoke. After this excursion, he is lucky not to be caught by the prowling police boats, which are grim faced and blue.

“Little Toot” resolves in the future to be good and help his father, “Big Toot”.

His first attempt ends in disaster; a vast liner ends up spinning uncontrollably to land in the streets of New York, surrounded by bent and battered skyscrapers.

“Little Toot” is escorted out to sea — past the 12 mile limit — by the police boats and left there to the mercy for whatever fate might have in store for him.

A storm blows up. As the sky thunders and the waves crash, a chorus of huge, red, sharked-jawed buoys verbally chastise him “Shame! Shame! Too bad! Too Bad!”

“Little Toot” is such a reject that even the circling beam of a nearby lighthouse detours around him. This is bad enough, but then the storm really hits. The poor little tug is having difficulty staying afloat when a rocket flare lights up the sky; a liner is in distress out by the dreaded rocks. “Little Toot” promptly sends back an SOS to the New York tugs and they immediately send out a rescue expedition, but he is by far the nearest to the liner and so it is really up to him.

Hooked up to the liner, he strains to pull it clear but to no avail… until a bolt of lightning hits his stern. The effect is electrifying in both senses of the word and in no time “Little Toot” has saved the liner and the day. He returns to a hero’s welcome, and at last — and for the first time — his father, “Big Toot”, has cause to be proud of him.

Stills of “Little Toot” do not so him justice; he is not the flat neutral character he appears to be in them. The drawing of him is simple, yet somehow it conveys the fact that he is essentially a naughty child — infuriating much of the time but nevertheless very lovable. His father, “Big Toot”, comes across as a gritty workin’ man, gruff and reserved yet with a heart of gold. Just how the Disney animators achieved such is impossible to tell; perhaps they did not know it themselves, but did it all by instinct.

That last paragraph sums up again what makes Disney characters come to life and why we can feel that they are real and relate to them so well. That’s the magic that character animation is best at and Disney does it best of all.”

This book may take up a bit of space on the coffee table or a shelf, but it is worth the effort. Again it is a valuable reference source and a can provide inspiration as well as background. It may be hard to find in the stores, but if you look, it might even be among the bargain tables. Trust me, it’s worth the effort.

Now there have been several editions of the book, and it is about time for another edition to make the rounds, we can hope. Again it would make a great electronic version complete with a database feature. Throw in a few short movie clips for some of the better known characters and or features and they would have no trouble selling, I’m certain.

If you’re serious in looking for a copy of this title, Amazon does have both new and used of the first and third editions for sale. The 1987 1st edition or the 1998 3rd edition can be found at those links.

Next week? That’s something I’m pondering right now. A couple of good things to share with you all…

On the donation front for the Message Boards, kudos to our own Instidude for doing his part by sharing a donation with us. As nice as that is, we have about two-thirds of what we need to make the advertisements go away again. Every bit helps folks, no matter how much. So think about it, will you?

History

The Evolution and History of Mickey’s ToonTown

Disneyland in Anaheim, California, holds a special place in the hearts of Disney fans worldwide, I mean heck, it’s where the magic began after all. Over the years it’s become a place that people visit in search of memorable experiences. One fan favorite area of the park is Mickey’s Toontown, a unique land that lets guests step right into the colorful, “Toony” world of Disney animation. With the recent reimagining of the land and the introduction of Micky and Minnies Runaway Railway, have you ever wondered how this land came to be?

There is a fascinating backstory of how Mickey’s Toontown came into existence. It’s a tale of strategic vision, the influence of Disney executives, and a commitment to meeting the needs of Disney’s valued guests.

The Beginning: Mickey’s Birthdayland

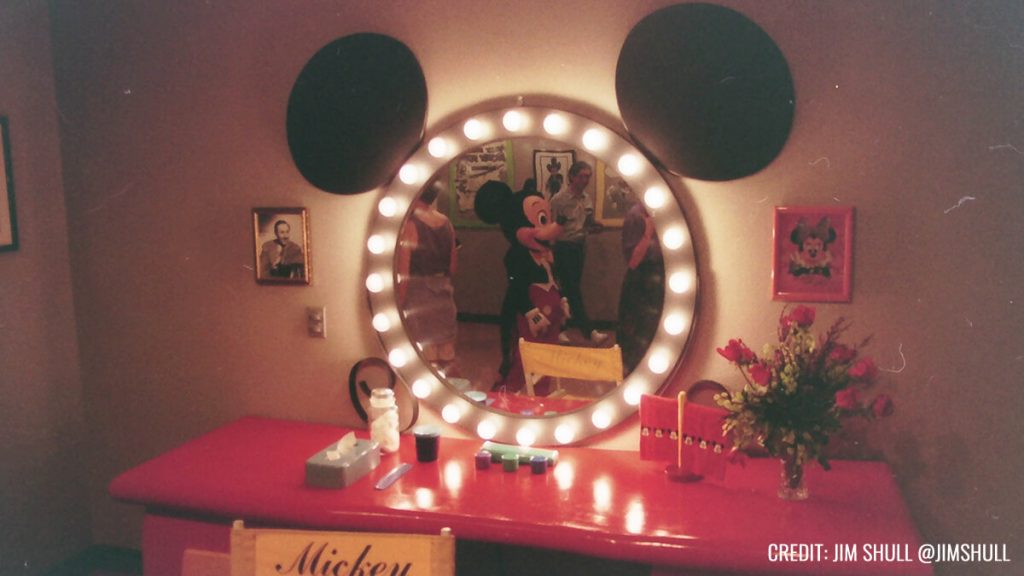

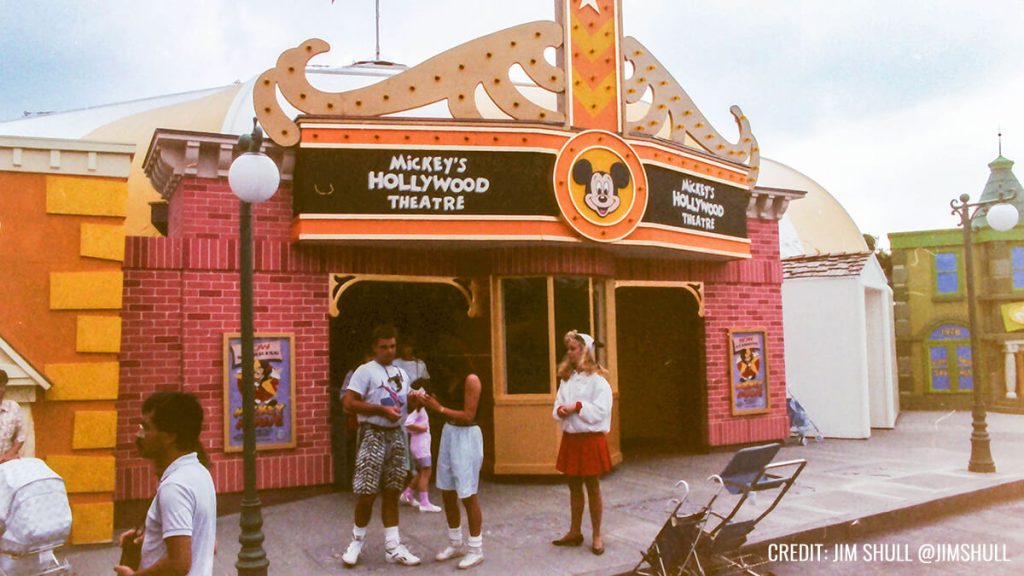

The story of Mickey’s Toontown starts with Mickey’s Birthdayland at Walt Disney World’s Magic Kingdom. Opened in 1988 to celebrate Mickey Mouse’s 60th birthday, this temporary attraction was met with such overwhelming popularity that it inspired Disney executives to think bigger. The idea was to create a permanent, immersive land where guests could step into the animated world of Mickey Mouse and his friends.

In the early ’90s, Disneyland was in need of a refresh. Michael Eisner, the visionary leader of The Walt Disney Company at the time, had an audacious idea: create a brand-new land in Disneyland that would celebrate Disney characters in a whole new way. This was the birth of Mickey’s Toontown.

Initially, Disney’s creative minds toyed with various concepts, including the idea of crafting a 100-Acre Woods or a land inspired by the Muppets. However, the turning point came when they considered the success of “Who Framed Roger Rabbit.” This film’s popularity and the desire to capitalize on contemporary trends set the stage for Toontown’s creation.

From Concept to Reality: The Birth of Toontown

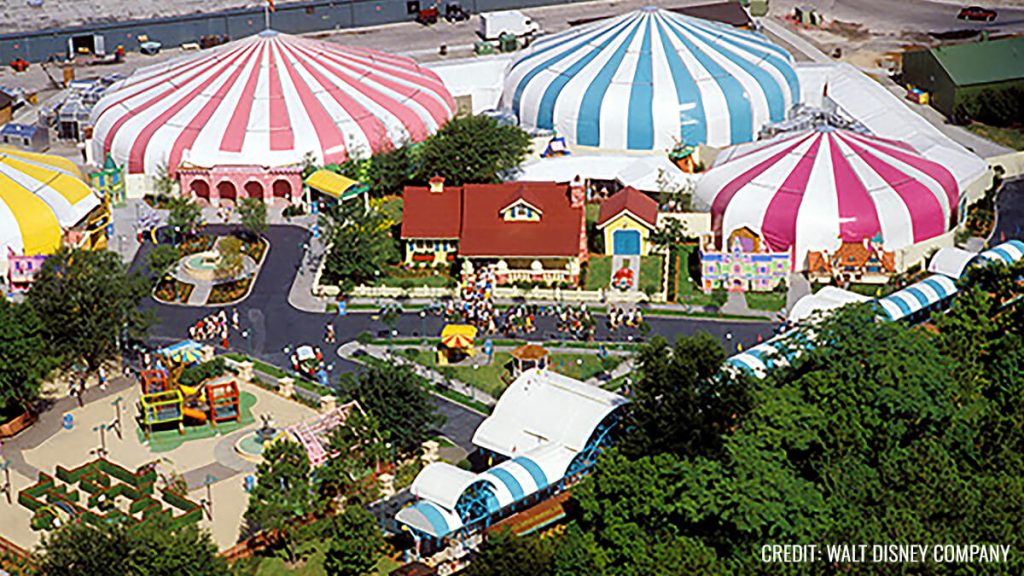

In 1993, Mickey’s Toontown opened its gates at Disneyland, marking the first time in Disney Park history where guests could experience a fully realized, three-dimensional world of animation. This new land was not just a collection of attractions but a living, breathing community where Disney characters “lived,” worked, and played.

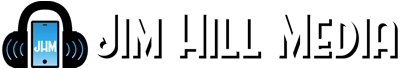

Building Challenges: Innovative Solutions

The design of Mickey’s Toontown broke new ground in theme park aesthetics. Imagineers were tasked with bringing the two-dimensional world of cartoons into a three-dimensional space. This led to the creation of over 2000 custom-built props and structures that embodied the ‘squash and stretch’ principle of animation, giving Toontown its distinctiveness.

And then there was also the challenge of hiding the Team Disney Anaheim building, which bore a striking resemblance to a giant hotdog. The Imagineers had to think creatively, using balloon tests and imaginative landscaping to seamlessly integrate Toontown into the larger park.

Key Attractions: Bringing Animation to Life

Mickey’s Toontown featured several groundbreaking attractions. “Roger Rabbit’s Car Toon Spin,” inspired by the movie “Who Framed Roger Rabbit,” became a staple of Toontown, offering an innovative ride experience. Gadget’s Go-Coaster, though initially conceived as a Rescue Rangers-themed ride, became a hit with younger visitors, proving that innovative design could create memorable experiences for all ages.

Another crown jewel of Toontown is Mickey’s House, a walkthrough attraction that allowed guests to explore the home of Mickey Mouse himself. This attraction was more than just a house; it was a carefully crafted piece of Disney lore. The house was designed in the American Craftsman style, reflecting the era when Mickey would have theoretically purchased his first home in Hollywood. The attention to detail was meticulous, with over 2000 hand-crafted, custom-built props, ensuring that every corner of the house was brimming with character and charm. Interestingly, the design of Mickey’s House was inspired by a real home in Wichita Falls, making it a unique blend of real-world inspiration and Disney magic.

Mickey’s House also showcased Disney’s commitment to creating interactive and engaging experiences. Guests could make themselves at home, sitting in Mickey’s chair, listening to the radio, and exploring the many mementos and references to Mickey’s animated adventures throughout the years. This approach to attraction design – where storytelling and interactivity merged seamlessly – was a defining characteristic of ToonTown’s success.

Executive Decisions: Shaping ToonTown’s Unique Attractions

The development of Mickey’s Toontown wasn’t just about creative imagination; it was significantly influenced by strategic decisions from Disney executives. One notable input came from Jeffrey Katzenberg, who suggested incorporating a Rescue Rangers-themed ride. This idea was a reflection of the broader Disney strategy to integrate popular contemporary characters and themes into the park, ensuring that the attractions remained relevant and engaging for visitors.

In addition to Katzenberg’s influence, Frank Wells, the then-President of The Walt Disney Company, played a key role in the strategic launch of Toontown’s attractions. His decision to delay the opening of “Roger Rabbit’s Car Toon Spin” until a year after Toontown’s debut was a calculated move. It was designed to maintain public interest in the park by offering new experiences over time, thereby giving guests more reasons to return to Disneyland.

These executive decisions highlight the careful planning and foresight that went into making Toontown a dynamic and continuously appealing part of Disneyland. By integrating current trends and strategically planning the rollout of attractions, Disney executives ensured that Toontown would not only capture the hearts of visitors upon its opening but would continue to draw them back for new experiences in the years to follow.

Global Influence: Toontown’s Worldwide Appeal

The concept of Mickey’s Toontown resonated so strongly that it was replicated at Tokyo Disneyland and influenced elements in Disneyland Paris and Hong Kong Disneyland. Each park’s version of Toontown maintained the core essence of the original while adapting to its cultural and logistical environment.

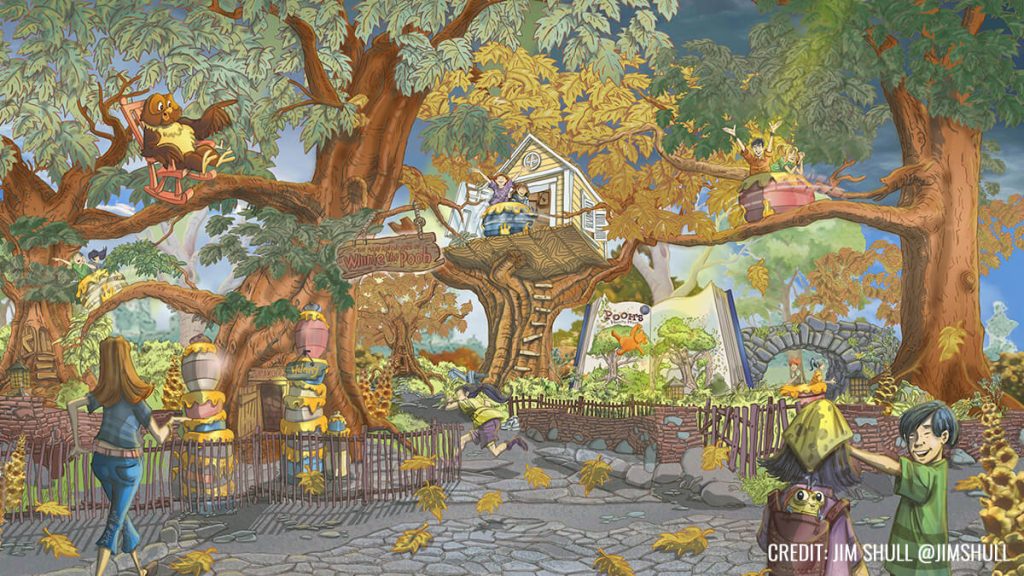

Evolution and Reimagining: Toontown Today

As we approach the present day, Mickey’s Toontown has recently undergone a significant reimagining to welcome “Mickey & Minnie’s Runaway Railway” in 2023. This refurbishment aimed to enhance the land’s interactivity and appeal to a new generation of Disney fans, all while retaining the charm that has made ToonTown a beloved destination for nearly three decades.

Dive Deeper into ToonTown’s Story

Want to know more about Mickey’s Toontown and hear some fascinating behind-the-scenes stories, then check out the latest episode of Disney Unpacked on Patreon @JimHillMedia. In this episode, the main Imagineer who worked on the Toontown project shares lots of interesting stories and details that you can’t find anywhere else. It’s full of great information and fun facts, so be sure to give it a listen!

History

Unpacking the History of the Pixar Place Hotel

Pixar Place Hotel, the newly unveiled 15-story tower at the Disneyland Resort, has been making waves in the Disney community. With its unique Pixar-themed design, it promises to be a favorite among visitors.

However, before we delve into this exciting addition to the Disneyland Resort, let’s take a look at the fascinating history of this remarkable hotel.

The Emergence of the Disneyland Hotel

To truly appreciate the story of the Pixar Place Hotel, we must turn back the clock to the early days of Disneyland. While Walt Disney had the visionary ideas and funding to create the iconic theme park, he faced a challenge when it came to providing accommodations for the park’s visitors. This is where his friend Jack Wrather enters the picture.

Jack Wrather, a fellow pioneer in the television industry, stepped in to assist Walt Disney in realizing his dream. Thanks to the success of the “Lassie” TV show produced by Wrather’s company, he had the financial means to build a hotel right across from Disneyland.

The result was the Disneyland Hotel, which opened its doors in October 1955. Interestingly, the early incarnation of this hotel had more of a motel feel than a hotel, with two-story buildings reminiscent of the roadside motels popular during the 1950s. The initial Disneyland Hotel consisted of modest structures that catered to visitors looking for affordable lodging close to the park. While the rooms were basic, it marked the beginning of something extraordinary.

The Evolution: From Emerald of Anaheim to Paradise Pier

As Disneyland’s popularity continued to soar, so did the demand for expansion and improved accommodations. In 1962, the addition of an 11-story tower transformed the Disneyland Hotel, marking a significant transition from a motel to a full-fledged hotel.

The addition of the 11-story tower elevated the Disneyland Hotel into a more prominent presence on the Anaheim skyline. At the time, it was the tallest structure in all of Orange County. The hotel’s prime location across from Disneyland made it an ideal choice for visitors. With the introduction of the monorail linking the park and the hotel, accessibility became even more convenient. Unique features like the Japanese-themed reflecting pools added to the hotel’s charm, reflecting a cultural influence that extended beyond Disney’s borders.

Japanese Tourism and Its Impact

During the 1960s and 1970s, Disneyland was attracting visitors from all corners of the world, including Japan. A significant number of Japanese tourists flocked to Anaheim to experience Walt Disney’s creation. To cater to this growing market, it wasn’t just the Disneyland Hotel that aimed to capture the attention of Japanese tourists. The Japanese Village in Buena Park, inspired by a similar attraction in Nara, Japan, was another significant spot.

These attractions sought to provide a taste of Japanese culture and hospitality, showcasing elements like tea ceremonies and beautiful ponds with rare carp and black swans. However, the Japanese Village closed its doors in 1975, likely due to the highly competitive nature of the Southern California tourist market.

The Emergence of the Emerald of Anaheim

With the surge in Japanese tourism, an opportunity arose—the construction of the Emerald of Anaheim, later known as the Disneyland Pacific Hotel. In May 1984, this 15-story hotel opened its doors.

What made the Emerald unique was its ownership. It was built not by The Walt Disney Company or the Oriental Land Company (which operated Tokyo Disneyland) but by the Tokyu Group. This group of Japanese businessmen already had a pair of hotels in Hawaii and saw potential in Anaheim’s proximity to Disneyland. Thus, they decided to embark on this new venture, specifically designed to cater to Japanese tourists looking to experience Southern California.

Financial Challenges and a Changing Landscape

The late 1980s brought about two significant financial crises in Japan—the crash of the NIKKEI stock market and the collapse of the Japanese real estate market. These crises had far-reaching effects, causing Japanese tourists to postpone or cancel their trips to the United States. As a result, reservations at the Emerald of Anaheim dwindled.

To adapt to these challenging times, the Tokyu Group merged the Emerald brand with its Pacific hotel chain, attempting to weather the storm. However, the financial turmoil took its toll on the Emerald, and changes were imminent.

The Transition to the Disneyland Pacific Hotel

In 1995, The Walt Disney Company took a significant step by purchasing the hotel formerly known as the Emerald of Anaheim for $35 million. This acquisition marked a change in the hotel’s fortunes. With Disney now in control, the hotel underwent a name change, becoming the Disneyland Pacific Hotel.

Transformation to Paradise Pier

The next phase of transformation occurred when Disney decided to rebrand the hotel as Paradise Pier Hotel. This decision aligned with Disney’s broader vision for the Disneyland Resort.

While the structural changes were limited, the hotel underwent a significant cosmetic makeover. Its exterior was painted to complement the color scheme of Paradise Pier, and wave-shaped crenellations adorned the rooftop, creating an illusion of seaside charm. This transformation was Disney’s attempt to seamlessly integrate the hotel into the Paradise Pier theme of Disney’s California Adventure Park.

Looking Beyond Paradise Pier: The Shift to Pixar Place

In 2018, Disneyland Resort rebranded Paradise Pier as Pixar Pier, a thematic area dedicated to celebrating the beloved characters and stories from Pixar Animation Studios. As a part of this transition, it became evident that the hotel formally known as the Disneyland Pacific Hotel could no longer maintain its Paradise Pier theme.

With Pixar Pier in full swing and two successful Pixar-themed hotels (Toy Story Hotels in Shanghai Disneyland and Tokyo Disneyland), Disney decided to embark on a new venture—a hotel that would celebrate the vast world of Pixar. The result is Pixar Place Hotel, a 15-story tower that embraces the characters and stories from multiple Pixar movies and shorts. This fully Pixar-themed hotel is a first of its kind in the United States.

The Future of Pixar Place and Disneyland Resort

As we look ahead to the future, the Disneyland Resort continues to evolve. The recent news of a proposed $1.9 billion expansion as part of the Disneyland Forward project indicates that the area surrounding Pixar Place is expected to see further changes. Disneyland’s rich history and innovative spirit continue to shape its destiny.

In conclusion, the history of the Pixar Place Hotel is a testament to the ever-changing landscape of Disneyland Resort. From its humble beginnings as the Disneyland Hotel to its transformation into the fully Pixar-themed Pixar Place Hotel, this establishment has undergone several iterations. As Disneyland Resort continues to grow and adapt, we can only imagine what exciting developments lie ahead for this iconic destination.

If you want to hear more stories about the History of the Pixar Place hotel, check our special edition of Disney Unpacked over on YouTube.

Stay tuned for more updates and developments as we continue to explore the fascinating world of Disney, one story at a time.

History

From Birthday Wishes to Toontown Dreams: How Toontown Came to Be

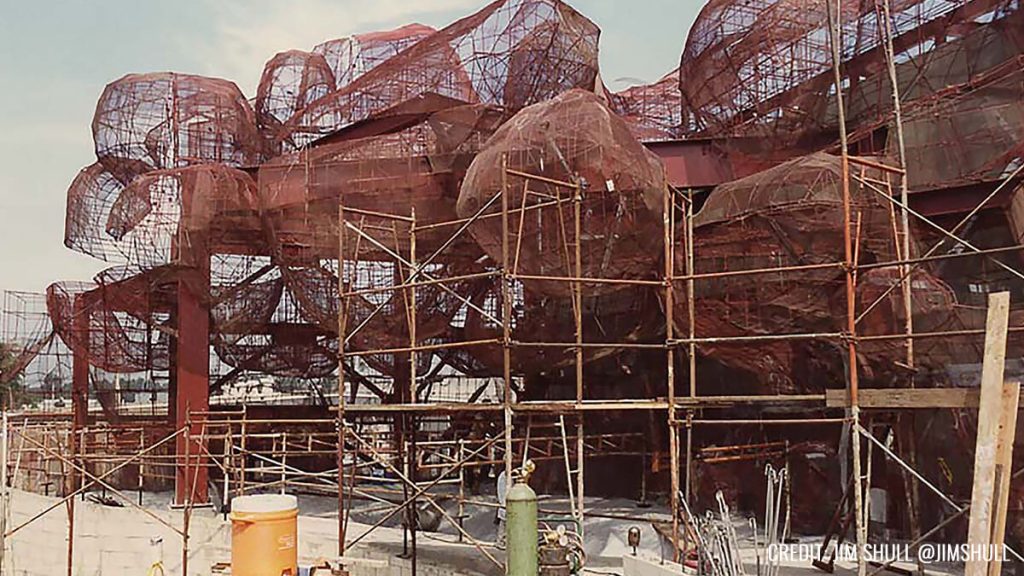

In the latest release of Episode 4 of Disney Unpacked, Len and I return, joined as always by Disney Imagineering legend, Jim Shull. This two-part episode covers all things Mickey’s Birthday Land and how it ultimately led to the inspiration behind Disneyland’s fan-favorite land, “Toontown”. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves here. It all starts in the early days at Disneyland.

Early Challenges in Meeting Mickey

Picture this: it’s the late 1970s and early 1980s, and you’re at Disneyland. You want to meet the one and only Mickey Mouse, but there’s no clear way to make it happen. You rely on Character Guides, those daily printed sheets that point you in Mickey’s general direction. But let’s be honest, it was like finding a needle in a haystack. Sometimes, you got lucky; other times, not so much.

Mickey’s Birthdayland: A Birthday Wish that Came True

Fast forward to the late 1980s. Disney World faced a big challenge. The Disney-MGM Studios Theme Park was under construction, with the company’s marketing machine in full swing, hyping up the opening of Walt Disney World’s third theme park, MGM Studios, in the Spring of 1989. This extensive marketing meant that many people were opting to postpone their family’s next trip to Walt Disney World until the following year. Walt Disney World needed something compelling to motivate guests to visit Florida in 1988, the year before Disney MGM Studios opened.

Enter stage left, Mickey’s Birthdayland. For the first time ever, an entire land was dedicated to a single character – and not just any character, but the mouse who started it all. Meeting Mickey was no longer a game of chance; it was practically guaranteed.

The Birth of Birthdayland: Creative Brilliance Meets Practicality

In this episode, we dissect the birth of Mickey’s Birthdayland, an initiative that went beyond celebrating a birthday. It was a calculated move, driven by guest feedback and a need to address issues dating back to 1971. Imagineers faced the monumental task of designing an experience that honored Mickey while efficiently managing the crowds. This required the perfect blend of creative flair and logistical prowess – a hallmark of Disney’s approach to theme park design.

Evolution: From Birthdayland to Toontown

The success of Mickey’s Birthdayland was a real game-changer, setting the stage for the birth of Toontown – an entire land that elevated character-centric areas to monumental new heights. Toontown wasn’t merely a spot to meet characters; it was an immersive experience that brought Disney animation to life. In the episode, we explore its innovative designs, playful architecture, and how every nook and cranny tells a story.

Impact on Disney Parks and Guests

Mickey’s Birthdayland and Toontown didn’t just reshape the physical landscape of Disney parks; they transformed the very essence of the guest experience. These lands introduced groundbreaking ways for visitors to connect with their beloved characters, making their Disney vacations even more unforgettable.

Beyond Attractions: A Cultural Influence

But the influence of these lands goes beyond mere attractions. Our episode delves into how Mickey’s Birthdayland and Toontown left an indelible mark on Disney’s culture, reflecting the company’s relentless dedication to innovation and guest satisfaction. It’s a journey into how a single idea can grow into a cherished cornerstone of the Disney Park experience.

Unwrapping the Full Story of Mickey’s Birthdayland

Our two-part episode of Disney Unpacked is available for your viewing pleasure on our Patreon page. And for those seeking a quicker Disney fix, we’ve got a condensed version waiting for you on our YouTube channel. Thank you for being a part of our Disney Unpacked community. Stay tuned for more episodes as we continue to “Unpack” the fascinating world of Disney, one story at a time.

-

News & Press Releases11 months ago

News & Press Releases11 months agoDisney Will Bring D23: The Ultimate Disney Fan Event to Anaheim, California in August 2024

-

History6 months ago

History6 months agoFrom Birthday Wishes to Toontown Dreams: How Toontown Came to Be

-

History6 months ago

History6 months agoUnpacking the History of the Pixar Place Hotel

-

History6 months ago

History6 months agoThe Evolution and History of Mickey’s ToonTown

-

News & Press Releases5 months ago

News & Press Releases5 months agoNew Updates and Exclusive Content from Jim Hill Media: Disney, Universal, and More

-

Film & Movies3 months ago

Film & Movies3 months agoHow Disney’s “Bambi” led to the creation of Smokey Bear

-

Merchandise4 months ago

Merchandise4 months agoIntroducing “I Want That Too” – The Ultimate Disney Merchandise Podcast