Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment

“Shrek 4D”, “Mickey’s Philharmagic” and the post modern theme park — Part II

Seth Kubersky’s intriguing new series concludes with a close look at “Shrek 4D,” including some great gags that got reportedly cut from the pre-show area of this new 3D film when Universal management suddenly got nervous.

Welcome back to the exciting world of Post-Modernism!

In the first part of this article, I discussed the Modernist influences found in the Walt Disney parks and attractions. This is not meant to imply that post-Modernism has not influenced, or been influenced by, the Mouse. After all, Andy Warhol, one of the pioneers of post-Modernism, famously appropriated the image of Mickey Mouse for his Pop Art. Post-Modern influences can be seen in several Disney animated features from the last couple decades. Most notably, the Robin William’s Genie in “Aladdin” is a purely post-Modern creation, anachronistically blending cultural and historical references to great comic effect. Segments of “Fantasia 2000” can be read as a post-Modern response to the decidedly Modernist “Fantasia”, as evidenced by the ironic juxtaposition of “serious” music with whimsical, “unserious” imagery that undercuts the composers’ intentions (see “Pomp and Circumstance”, “Rhapsody in Blue”).

Post-Modernism has also crept into recent Disney park attractions. Disney’s initial reluctance to put “characters” in EPCOT because they “didn’t fit” can be read in the light of the Modernist resistance to breaking down the barrier between “high culture” (the serious-minded educational aspirations of the original Future World) and “low culture” (silly cartoon characters). But with the Eisner era came a willingness to play with Disney’s image and the expectations of park visitors. The introduction of post-Modern aesthetics to Walt Disney World has been gradual and subtle, reflecting the creeping influence of post-Modernism in the larger culture. What would Walt have thought of Iago quipping at the end of the revamped Tiki Room, “I’m tired. I think I’ll go to the Hall of Presidents and take a nap”? Walt might not have been amused, but the self-awareness and irreverence towards a sacred icon would bring a smile to any post-Modernist’s face.

Ironically, the most identifiably post-Modernist attraction on Disney property isn’t based on a Disney property at all. The attraction is “MuppetVision 4D”, and it is arguably the most post-Modern theme park attraction pre-Shrek. This is appropriate, as the Muppets were post-Modern from their inception. During its first season, Saturday Night Live, which was at one time aggressively post-modern and counter-cultural, featured an early incarnation of the Muppets. The Muppet Show took elements of high culture, low culture, and no culture, threw them into a blender, and played gleefully with the results. If the sight of high-culture icons Rudolph Nureyev and Beverly Sills cavorting with felt puppets isn’t the very definition of post-modernism, then nothing is. And when it came time to turn the Muppets into an attraction, no effort was spared to subvert the very idea of theme park entertainment, in classic Muppet style.

Quick, what is the single funniest line in “MuppetVision 4D”? The line that perfectly encapsulates the attraction’s post-Modern sensibility? The line that makes me laugh out loud every time I hear it?

“We can’t, you fool! We’re bolted to the seats!”

This line, spoken by Statler and Waldorf at the very end of the show, seemed revolutionary to me when then attraction first opened. It represents a fundamental element of post-Modern art: self-awareness. It was, to my knowledge, the first time a character in a theme park attraction acknowledged that it was a theme park character, and made light of the fact. There is much of this “breaking the fourth wall” throughout the show, from Fozzie’s reference to the “cheesy 3D gags” found in earlier 3D films, to the literal destruction of the fourth wall of the theater at the show’s end, exposing theme park guests in the background. Another element of post-Modernism is irreverent disregard of historical icons, as seen in the disastrous patriotic finale (“It’s a glorious tribute to all nations, but mostly ours”). Every element, from the film parody posters in the queue to the many puns and inside jokes in the preshow, serves to playfully violate the audience’s suspension of disbelief. By subverting the expectation that theme park attractions should present a coherent self-contained narrative, the Muppets mock themselves, and the dominant Modernist aesthetic that pervades the rest of Disney.

These post-Modern elements are still the exception, not the rule, at Disney. But a short ride down I-4 in Orlando will bring you to a theme park seemingly built on post-Modern principles. Take a look at a publicity shot from Universal Studios Florida’s early years and you’ll immediately see what I mean. You’ll see a bizarre mix of celebrities and fictional characters. Marilyn Monroe rubs elbows with Laurel and Hardy, who interact with Woody Woodpecker and Doc Brown, and they’re right next to Beetlejuice and the Blues Brothers. Icons from various historical eras and genres are fearlessly juxtaposed, a hallmark of post-Modern Pop Art. This is in contrast to Disney publicity shots, which are always carefully composed to present a consistent aesthetic in which the characters all seem to exist in the same universe.

Post-Modern influences can be seen in the architecture of the park as well. All the Disney parks feature an entrance area with a consistent theme, leading to a distinct icon. This represents the Modernist impulse to present a single coherent narrative. Universal Studios, in contrast, has no central in-park icon to guide guests. Instead, guests are faced with an immediate choice between heading straight, towards the Production Central and New York areas, or to the right towards Hollywood and World Expo. Along the way, they will notice an eclectic mix of themes and architectural styles, without the gradual transitions between sections found in the Magic Kingdom. Throughout, the use of obvious facades and utilitarian architecture exposes the artificiality of the studio backlot theme, undercutting the notion of a “real” fantasy world. Twister and E.T. in particular feature behind-the-scenes studio props juxtaposed with “realistic” themed environments.

The design of many of the individual attractions is decidedly post-Modern. Most obviously, the Men In Black building borrows from a grab bag of architectural icons (the St. Louis arch, the World’s Fair towers) and aesthetic styles (science-fiction, 60’s kitsch). The Jaws preshow takes the premise of the film and explodes it by suggesting that the movie was a fictionalized account of real events. The queue video takes turns these “real” characters from a film famous for it’s dramatic tension into comic foils in a satire of talk shows, tourism, and children’s entertainment. And the Kongfrontation queue line broke down the barrier between artist and audience by inviting guests to participate in creating the graffiti that lined the walls.

Post-modern elements are not confined just to the original Universal park. They can be seen in fine form next door at Islands of Adventure. The “legend” of Port of Entry, IOA’s answer to Main Street USA, reads like a post-Modern manifesto: a melting pot where adventurers and explorers from all time periods and cultures have come to share ideas and build a new society. The Lost Continent takes the sacred myths of Greek, Arab, and Celtic culture and recycles them as pop-culture thrills. The entire Marvel comic universe, particularly the creations of Stan Lee, can be read as a post-Modern reaction to the Modernist DC superheroes. Rather than feature blandly heroic icons engaged in a black-and-white battle between good and evil, Marvel gave us ordinary people burdened by extraordinary powers, struggling with the demands of normal life in a morally ambiguous world. Jurassic Park is more self-reflective than a funhouse hall of mirrors: a theme park based on a film based on a book about a theme park. The success of IOA with critics and guests can be seen as proof that post-Modernism is no longer distracting or confusing, but rather is something that can be understood and enjoyed by Middle America.

Finally, we return to Universal Studios and the thesis of this article. The new Shrek 4D attraction, while not the first post-Modern attraction, is certainly the clearest and most deliberate expression of the aesthetic. From the moment you enter the queue until you exit the gift shop, you are engaged in a world that seeks to subvert traditional notions of what a theme park attraction should be. Much of this attitude can be attributed to the source material. Consider the ways that the film “Shrek” promoted the post-Modern agenda:

1) Juxtaposition of unrelated genres and historical references: Shrek takes a traditional fairy tale milieu, and mixes in a wide range of references from music, film, literature, and pop culture.

2) Irreverent disregard for authority and cultural myths: Shrek inverts the traditional fairy tale notions of the noble prince, helpless princess, and evil ogre. On another level, the film is a thinly-veiled attack on Michael Eisner and the Disney company, both respected symbols of American corporate culture.

3) Suspicion of dominant Western culture in favor of “authentic” non-Western culture: The plot of the film, based around Farquaad’s failed attempt to subjugate the fairy tale creatures, can be read as an indictment of Western efforts to oppress indigenous populations.

4) Playful acceptance of alternative cultural and sexual standards: The relationship between Shrek and Fiona, and between Donkey and the dragon, represent a rejection of the traditional romantic ideal found in most fairy tales.

Universal could have chosen to ignore these complex elements and use the Shrek characters for an amusing, if unchallenging, thrill ride. Instead they created an attraction that depends on humor based on these very aspects. This is unsurprising, since the same creative team that made the Shrek films was responsible for the attraction, a rarity in theme park entertainment. You will find clever, self-aware moments throughout the show. There are so many Star Wars references you might think you’re watching a Kevin Smith film, not to mention nods to Blues Brothers, Sleepy Hollow, and many more. The Disney-esque characters are abused mercilessly, especially poor Tinkerbell. Even the traditional notions of good-vs.-evil are subverted by the apologetic executioner.

Before I continue, I have a confession to make: “Shrek 4D” isn’t perfect. Yes, the film is very funny, the in-theater effects are effective (if a bit redundant), and the preshow and queue are witty. All the individual elements are very good to excellent. But they aren’t integrated as well as they might have been. The biggest problem is the muddy transition between the preshow and main show: while they are both very well done, they don’t connect seamlessly. If fact, the end of the preshow sets up a premise (being tortured by the ghost of Farquaad) that the main show does not follow up on. This leads to confusion of identity and perspective in the main film. The design of the main theater itself also could have been better renovated from the original Hitchcock space. The space is minimally themed, and is not large enough to accommodate the crowds drawn by this popular attraction. Some of the in-theater effects are overused to the point that they loose their surprise value by the end of the show. And the screen is significantly smaller than the one at “Mickey’s Philharmagic,” but this is made up for by the razor-sharp digital projection and the use of clever lighting effects on the walls. These problems don’t stop Shrek from being a great attraction, but they do hold it back from being a perfect one.

I also have to disagree with Jim Hill’s assessment that the improved queue is primarily responsible for Orlando’s “Shrek 4D” earning higher guest scores than the Hollywood version. Orlando’s queue has many brilliant touches, but they are not presented as well as they could have been. The queue itself is a simple outdoor switchback that has not been significantly changed from the Hitchcock days. The addition of castle-like architectural touches is mostly superficial, and the extended queue area is fairly barren. The video loop shown on the overhead monitors is also disappointing: it consists solely of material found on the Shrek DVD, contains frequent advertisements for the movie (available in the gift shop), and is so brief that you may see it 3 or more times during a typical wait. Finally, the best visual gags are positioned late in the queue were you are likely to rush past them.

Despite these problems, the posters and signs are worth slowing down to read. As you approach the attraction, take the time to examine all the signage. Even those that seem to be standard warning signs contain subtle (and not so subtle) gags. The running theme is a tweaking of theme park conventions, with a fairy tale twist. The “Lancelot” parking section sign is an obvious lift from the film. But the safety instructions posted to the right of the queue entrance, though easily mistaken for a boilerplate warning, contains detailed instructions for dwarves, fairies, and other magical guests. The faux newspaper posted in several areas (headline: “Lord Farquaad Rises From His Grave: Still Very Short”) is filled with clever news items that both set up the show and give guests a chuckle.

Better still are the satirical movie and attraction advertisements to the left of the building entrance. Several of these are dead-on parodies of the classic Disney attraction posters that can be seen under the Main Street USA train station. My favorite: “The Enchanted Tick Room.” Another poster advertises a flying Donkey ride (shades of Dumbo) that promises “you’ll toss your teacups.”

Once you are in the pre-show itself, take a careful look around the room. In addition to the “Happiest Totalitarian Kingdom on Earth” sign, there are many other theme park parodies. Of particular note is the “Dulac Express” sign, an elaborate satire of Disney’s Fastpass.

But the best part of the queue is the Dulac Community Bulletin Board. Unfortunately positioned so that most guests will never be able to read all the gags, it is a glassed-in board covered with clever notices and advertisements. The premise is that — following the death of Farquaad — an underground fairy tale economy has come out of the closet. The want ads and announcements satirize commercial advertising, personal ads, and images of goody-goody childhood characters.

As wonderful as this Bulletin Board is, there was an earlier prototype that was even more daring. This early version of the Bulletin Board was briefly exhibited during the construction phase of the Shrek attraction. This mockup was quickly removed, and certain elements were changed or removed (for reasons that will soon be obvious) after vetting by the creative and legal departments. Some elements remained unchanged on the final prop that guests see today, but a few of the best gags were sanitized. Fortunately, I was able to document the prototype before it disappeared. And so, we conclude our journey through the post-Modern world of Shrek with some lost-and-found comedy gems. I present here a few of my most subversive favorites:

Tired of your Day Job? Do you want to make more money? Yes! You too can get that career you’ve been daydreaming about when you take Knight School classes. Take exciting courses in Steed Repair, Dragon Wrangling, Mandolin Restringing, Book Keeping, Accounting, Crossbow Repair, or get your degree in either Business Management or Falconry. Call the Knight School of Duloc and ask for Lance. You’ll like him A lot!

Free to Be Happily Ever After: Fairy Tale Survivors’ Support Group. What to do now that you’re out of the Woods.

“It was pretty rough going there for a while… I was a real boy, but that wasn’t enough for me anymore. I guess the low point would have to be when I dropped 20 pounds in 11 seconds after a foolish episode with Geppetto’s belt sander one night. I was hitting the furniture polish pretty hard, but then I took the pledge. Fairy tale Survivor’s support group turned me around, and it can do the same for you.”

Announcement: Lost fire-breathing Dragon. Very affectionate. Loves people and Animals. Answers to the name Mr. Sniffles.

“Single shut-in princess seeks anyone with a romantic spirit and a ladder. Must like big hair.”

Fairy Tale Ale Malt Liquor: You’ll Think You Can Fly (with an illustration of a drunken Tinkerbell)

Announcement: Burned my crops and barbecued my sheep. Please collect him ASAP. Just look for the scorch mark where my house used to be – corner of Maple and oh gawd, he’s coming right for me!

Personal Ad: “Wanna go to Pleasure Island? Single wooden male seeks female who can really work my strings. You must like splinters. Try me, I’ll grow on you… No lie!”

Personal Ad: “Are you looking for Prince Charming? Don’t be fooled by appearances. One kiss will transform your image of me. Love me, I’m tongue-tied. Hop on up to my totally fly pad.”

FOE’S: The Villain’s Tavern

You’ve a hard day at work turning straw into gold, or you’ve spent all week trying a glass slipper on every damsel in the country… it’s time! Kick off those glass slippers, and knock back a cold one in the comfort of Duloc’s foremost Fairy Tale Sports Tavern, Foe’s. Can’t get tickets to tournament day? We’re joust the place for you! Watch the games on our 32-inch magic mirror. And remember, Tuesday night is “Little Wooden Boy’s Night!”

Happy Hour: 5:00pm – 6:00pm

Grumpy Hour: 6:00pm – 7:00pm

Sleepy Hour: 7:00pm – 8:00pm

Dopey Hour: 8:00pm – 9:00pm

Drunkenly Calling Old Girlfriends Hour: 3:00am – 4:00am

Single Princess seeks prince or better. Seven little men can’t be wrong! You’ve had the rest, now try the fairest of them all.

Relationship moving too slowly? Well I may be just the thing you’re hungering for, but you’ll have to catch me first! I’m as fast as fast can be. I’ve got something for your sweet tooth.

Like hairy guys? Looking for a Big Bad boy to huff and puff and blow your mind? Not all the guys are wolves, but this one is.

Cottage to Let: 2 Bedroom, 2 Cauldron split-level Gingerbread house, with Gumdrop tile ceilings, cackle lighting, and wall-to-wall frosting – perfect for children (“wink”). Forbidden woods adjacent. Completely remodeled dungeon with all new torture equipment. Above ground bottomless pit. Cavern for dragon. No pets!

And finally, the piece de resistance (how did this ever get displayed in a family park?):

“Tri-curious? Think all the available guys are pigs? Well, why settle for one when you can have three. You’ve had the rest, now try the other white meat.”

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment

Disney and Macy’s 90-Year Thanksgiving Day Parade Partnership: From Mickey’s First Balloon to Minnie’s Big Debut

Now, folks, if you’re like me, Thanksgiving just wouldn’t be the same without a coffee, a cozy seat, and Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade on the TV. And if you’re really like me, you’re watching for one thing: Disney balloons floating down 34th Street. Ever wondered how Mickey, Donald, and soon Minnie Mouse found their way into this beloved New York tradition? Well, grab your popcorn because we’re diving into nearly 90 years of Disney’s partnership with Macy’s.

The Very First Parade and the Early Days of Balloons

The Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade goes way back to 1924, but if you can believe it, balloons weren’t part of the festivities until 1927. That first lineup included Felix the Cat, a dragon, and a toy soldier, all towering above the crowds. Back then, Macy’s had a pretty wild idea to end the parade: they would let the balloons drift off into the sky, free as birds. But this wasn’t just Macy’s feeling generous. Each balloon had a message attached, offering a $100 reward (about $1,800 in today’s dollars) for anyone who returned it to the flagship store on 34th Street.

And here’s where it gets interesting. This tradition carried on for a few years, right up until 1932, when Felix the Cat almost took down a plane flying over New York City! Imagine that—you’re flying into LaGuardia, and suddenly, there’s a 60-foot balloon drifting toward your wing. Needless to say, that was the end of Macy’s “fly away” stunt, and from then on, the balloons have stayed firmly grounded after the parade ends.

1934: Mickey Mouse Floats In, and Disney Joins the Parade

It was 1934 when Mickey Mouse finally made his grand debut in the Macy’s parade. Rumor has it Walt Disney himself collaborated with Macy’s on the design, and by today’s standards, that first Mickey balloon was a bit of a rough cut. This early Mickey had a hotdog-shaped body, and those oversized ears gave him a slightly lopsided look. But no one seemed to mind. Mickey was there, larger than life, floating down the streets of New York, and the crowd loved him.

Mickey wasn’t alone that year. He was joined by Pluto, Horace Horsecollar, and even the Big Bad Wolf and Practical Pig from The Three Little Pigs, making it a full Disney lineup for the first time. Back then, Disney wasn’t yet the entertainment powerhouse we know today, so for Walt, getting these characters in the parade meant making a deal. Macy’s required its star logo to be featured on each Disney balloon—a small concession that set the stage for Disney’s long-standing presence in the parade.

Duck Joins and Towers Over Mickey

A year later, in 1935, Macy’s introduced Donald Duck to the lineup, and here’s where things got interesting. Mickey may have been the first Disney character to float through the parade, but Donald made a huge splash—literally. His balloon was an enormous 60 feet tall and 65 feet long, towering over Mickey’s 40-foot frame. Donald quickly became a fan favorite, appearing in the lineup for several years before being retired.

Fast-forward a few decades, and Donald was back for a special appearance in 1984 to celebrate his 50th birthday. Macy’s dug the balloon out of storage, re-inflated it, and sent Donald down 34th Street once again, bringing a bit of nostalgia to the holiday crowd.

A Somber Parade in 2001

Now, one of my most memorable trips to the parade was in 2001, just weeks after the 9/11 attacks. Nancy and I, along with our friends, headed down to New York, and the mood was something I’ll never forget. We watched the start of the parade from Central Park West, but before that, we went to the Museum of Natural History the night before to see the balloons being inflated. They were covered in massive cargo nets, with sandbags holding them down. It’s surreal to see these enormous balloons anchored down before they’re set free.

That year, security was intense, with police lining the streets, and then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani rode on the Big Apple float to roaring applause. People cheered his name, waving and shouting as he passed. It felt like the entire city had turned out to show their resilience. Even amidst all the heightened security and tension, seeing those balloons—brought a bit of joy back to the city.

Balloon Prep: From New Jersey’s MetLife Stadium to California’s D23 Expo

Each year before the parade, Macy’s holds a rehearsal event known as Balloon Fest at MetLife Stadium in New Jersey. This is where handlers get their first crack at guiding the balloons, practicing with their parade masters, and learning the ropes—literally. It’s an entire production unto itself, with dozens of people rehearsing to make sure these enormous inflatables glide smoothly down the streets of New York on parade day.

In 2015, Macy’s took the balloon show on the road, bringing their Buzz Lightyear balloon out to California for the D23 Expo. I was lucky enough to be there, and watching Buzz get inflated piece by piece in the Anaheim Convention Center parking lot was something to behold. Each section was filled with helium in stages, and when they got around to Buzz’s lower half, well, there were more than a few gas-related jokes from the crowd.

These balloons seem to have a personality all their own, and seeing one like Buzz come to life up close—even outside of New York—had all the excitement and anticipation of the real deal.

Mickey’s Comeback as a Bandleader and Sailor Mickey

After a long hiatus, Mickey Mouse made his return to the Macy’s parade in 2000, this time sporting a new bandleader outfit. Nine years later, in 2009, Sailor Mickey joined the lineup, promoting Disney Cruise Line with a nautical twist. Over the past two decades, Disney has continued to enchant parade-goers with characters like Buzz Lightyear in 2008 and Olaf from Frozen in 2017. These balloons keep Disney’s iconic characters front and center, drawing in both longtime fans and new viewers.

But ever wonder what happens to the balloons after they reach the end of 34th Street? They don’t just disappear. Each balloon is carefully deflated, rolled up like a massive piece of laundry, and packed into storage bins. From there, they’re carted back through the Lincoln Tunnel to Macy’s Parade Studio in New Jersey, where they await their next flight.

Macy’s Disney Celebration at Hollywood Studios

In 1992, Macy’s took the spirit of the parade down to Disney-MGM Studios in Orlando. After that year’s parade, several balloons—including Santa Goofy, Kermit the Frog, and Betty Boop—were transported to Hollywood Studios, re-inflated, and anchored along New York Street as part of a holiday display. Visitors could walk through this “Macy’s New York Christmas” setup and see the balloons up close, right in the middle of the park. While this display only ran for one season, it paved the way for the Osborne Family Spectacle of Dancing Lights, which became a holiday staple at the park for years to come.

Minnie Mouse’s Long-Awaited Debut in 2024

This year, Minnie Mouse will finally join the parade, making her long-overdue debut. Macy’s is rolling out the red carpet for Minnie’s arrival with special pop-up shops across the country, where fans can find exclusive Minnie ears, blown-glass ornaments, T-shirts, and more to celebrate her first appearance in the Thanksgiving Day Parade.

For those lucky enough to catch the parade this year, you’ll see Minnie take her first float down 34th Street, decked out in her iconic red bow and polka-dot dress. Macy’s and Disney are also unveiling a new Disney Cruise Line float honoring all eight ships, including the latest, the Disney Treasure.

As always, I’ll be watching from my favorite chair, coffee in hand, as Minnie makes her grand entrance. The 98th annual Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade airs live on NBC, and it’s a tradition you won’t want to miss—whether you’re on 34th Street or tuning in from home.

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment

Disney’s Forgotten Halloween Event: The Original Little Monsters on Main Street

When most Disney fans think of Halloween in the parks, they immediately picture Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party at Walt Disney World or the Oogie Boogie Bash at Disneyland Resort. But before those events took over as the must-attend spooky celebrations, there was a little-known event at Disneyland called Little Monsters on Main Street. And its origins? Well, they go all the way back to the 1980s, during a time when America was gripped by fear—the Satanic Panic.

You see, back in the mid-1980s, parents were terrified that Halloween had become dangerous. Urban legends about drug-laced candy or razor blades hidden in apples were widespread, and many parents felt they couldn’t let their kids out of sight for even a moment. Halloween, which was once a carefree evening of trick-or-treating in the neighborhood, had suddenly become a night filled with anxiety.

This is where Disneyland’s Little Monsters on Main Street came in.

The Origins of Little Monsters on Main Street

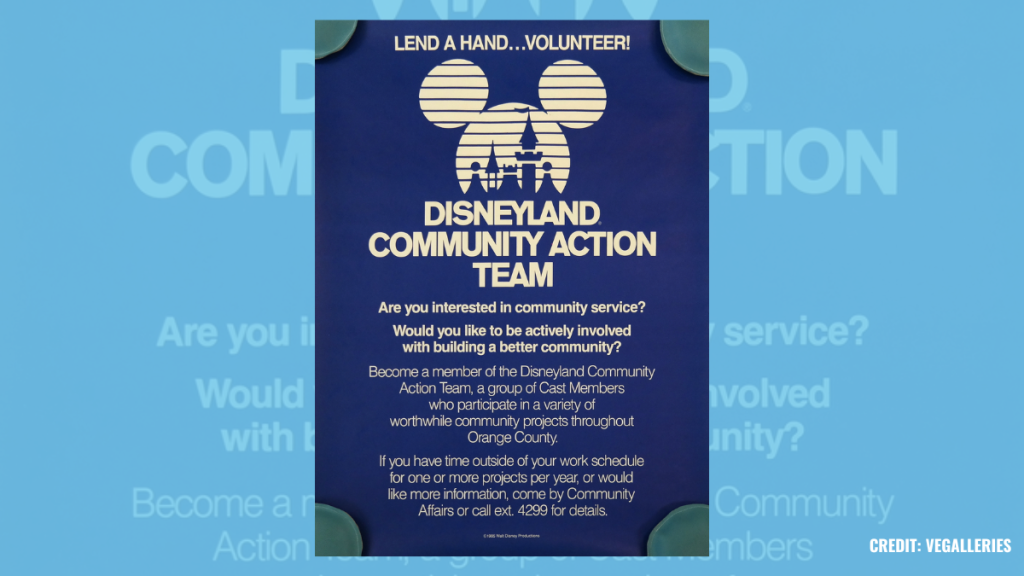

Back in 1989, the Disneyland Community Action Team—later known as the VoluntEARS—decided to create a safe, nostalgic Halloween experience for Cast Members and their families. Many schools in the Anaheim area were struggling to provide basic school supplies to students, and the VoluntEARS saw an opportunity to combine a safe Halloween with a charitable cause. Thus, Little Monsters on Main Street was born.

This event was not open to the general public. Only Disneyland Cast Members could purchase tickets, which were initially priced at just $5 each. Cast Members could bring their kids—but only as many as were listed as dependents with HR. And even then, the park put a cap on attendance: the first event was limited to just 1,000 children.

A Unique Halloween Experience

Little Monsters on Main Street wasn’t just another Halloween party. It was designed to give kids a safe, fun environment to enjoy trick-or-treating, much like the good old days. On Halloween night in 1989, kids in costume wandered through Disneyland with their pillowcases, visiting 20 different trick-or-treat stations. They also had the chance to ride a few of their favorite Fantasyland attractions, all after the park had closed to the general public.

The event was run entirely by the VoluntEARS—about 200 of them—who built and set up all the trick-or-treat stations themselves. They arrived at Disneyland before the park closed and, as soon as the last guest exited, they began setting up stations across Main Street, Adventureland, Frontierland, Fantasyland, and Tomorrowland. The event ran from 7:30 to 9:30 p.m., and by the time the last pillowcase-wielding kid left, the VoluntEARS cleaned everything up, making sure the park was ready for the next day’s operations.

It wasn’t just candy and rides, though. The event featured unique entertainment, like a Masquerade Parade down Main Street, U.S.A., where kids could show off their costumes. And get this—Disneyland even rigged up a Cast Member dressed as a witch to fly from the top of the Matterhorn to Frontierland on the same wire that Tinker Bell uses during the fireworks. Talk about a magical Halloween experience!

The Haunted Mansion “Tip-Toe” Tour

Perhaps one of the most memorable parts of Little Monsters on Main Street was the special “tip-toe tour” of the Haunted Mansion. Now, Disneyland’s Haunted Mansion can be a pretty scary attraction for younger kids, so during this event, Disney left the doors to the Stretching Room and Portrait Gallery wide open. This allowed kids to walk through and peek at the Haunted Mansion’s spooky interiors without actually having to board the Doom Buggies. For those brave enough to ride, they could, of course, take the full trip through the Haunted Mansion—or they could take the “chicken exit” and leave, no harm done.

Growing Success and a Bigger Event

Thanks to the event’s early success, Little Monsters on Main Street grew in size. By 1991, the attendance cap had been raised to 2,000 kids, and Disneyland added more activities like magic shows and hayrides. They also extended the event’s hours, allowing kids to enjoy the festivities until 10:30 p.m.

In 2002, the event moved over to Disney California Adventure, where it could accommodate even more kids—up to 5,000 in its later years. The name was also shortened to just Little Monsters, since it was no longer held on Main Street. This safe, family-friendly Halloween event continued for several more years, with the last mention of Little Monsters appearing in the Disneyland employee newsletter in 2008. Though some Cast Members recall the event continuing until 2012, it eventually made way for Disney’s more public-facing Halloween events.

From Little Monsters to Mickey’s Not-So-Scary and Oogie Boogie Bash

Starting in the early 2000s, Disney began realizing the potential of Halloween-themed after-hours events for the general public. These early versions of Mickey’s Halloween Party and Mickey’s Halloween Treat eventually evolved into today’s Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party and Oogie Boogie Bash. Unfortunately, this also marked the end of the intimate, Cast Member-exclusive Little Monsters event, but it paved the way for the large-scale Halloween celebrations we know and love today.

While it’s bittersweet to see Little Monsters on Main Street fade into Disney history, its legacy lives on through these modern Halloween parties. And even though Cast Members now receive discounted tickets to Mickey’s Not-So-Scary and Oogie Boogie Bash, the special charm of an event created specifically for Disney’s employees and their families remains something worth remembering.

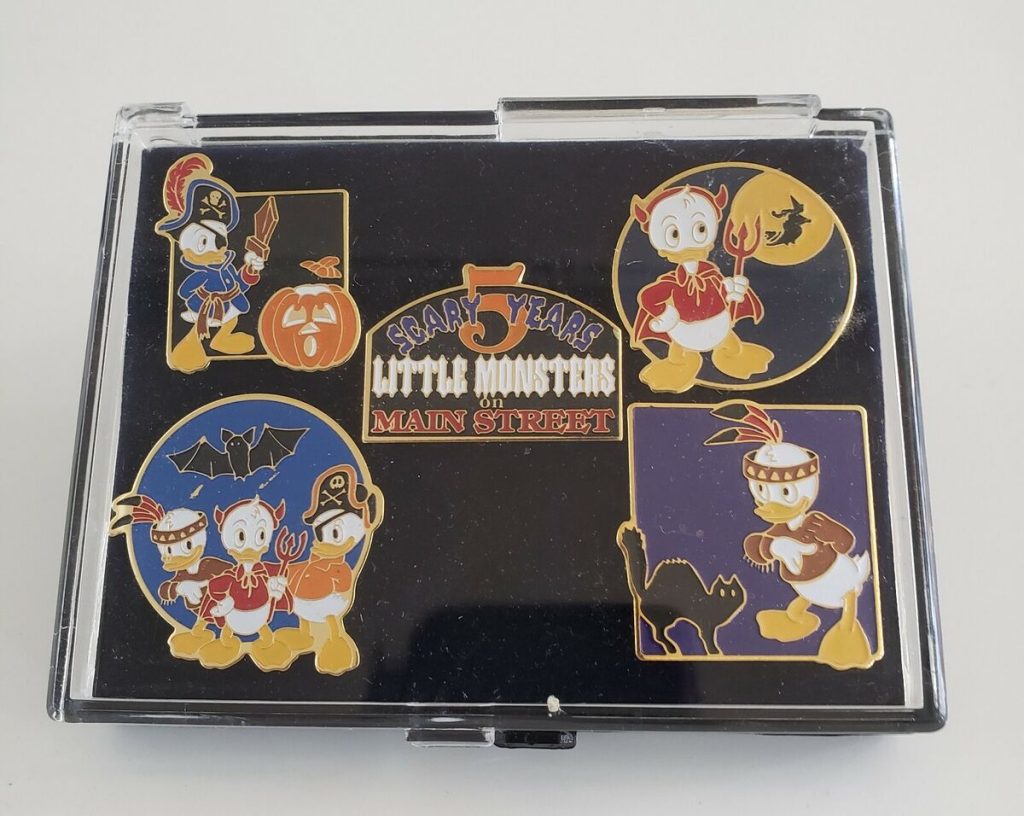

The Merch: A Piece of Little Monsters History

For Disney collectors, the exclusive merchandise created for Little Monsters on Main Street is still out there. You can find pins, name tags, and themed pillowcases on sites like eBay. One of the coolest collectibles is a 1997 cloisonné pin set featuring Huey, Dewey, and Louie dressed as characters from Hercules. Other sets paid tribute to the Main Street Electrical Parade and Pocahontas, while the pillowcases were uniquely designed for each year of the event.

While Little Monsters on Main Street may be gone, it’s a fascinating piece of Disneyland history that played a huge role in shaping the Halloween celebrations we enjoy at Disney parks today.

Want to hear more behind-the-scenes stories like this? Be sure to check out I Want That Too, where Lauren and I dive deep into the history behind Disney’s most beloved attractions, events, and of course, merchandise!

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment

The Story of Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party: From One Night to a Halloween Family Tradition

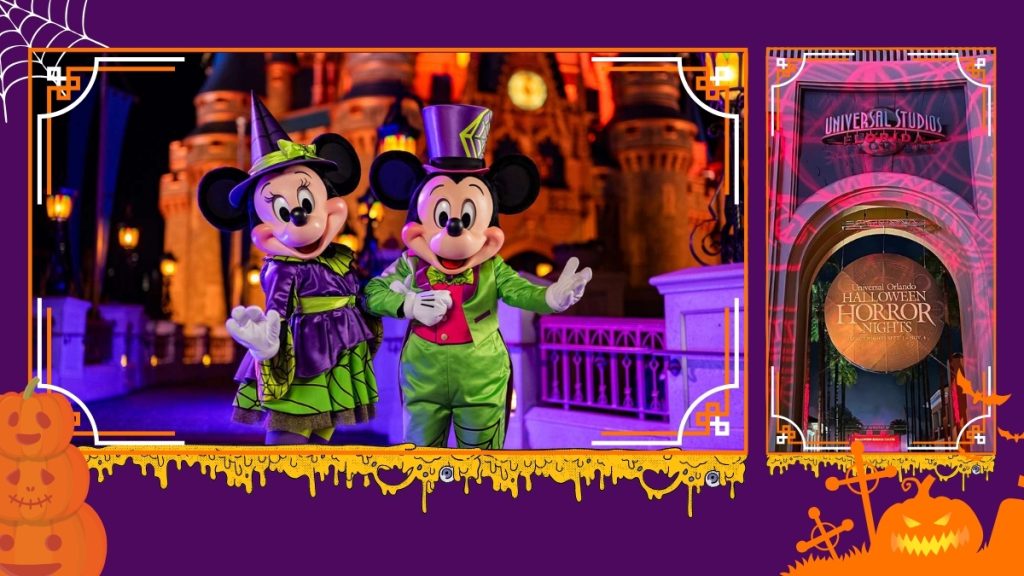

The spooky season is already in full swing at Disney parks on both coasts. On August 9th, the first of 38 Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party (MNSSHP) nights for 2024 kicked off at Florida’s Magic Kingdom. Meanwhile, over at Disney California Adventure, the Oogie Boogie Bash began on August 23rd and is completely sold out across its 27 dates this year.

Looking back, it’s incredible to think about how these Halloween-themed events have grown. But for Disney, the idea of charging guests for Halloween fun wasn’t always a given. In fact, when the very first Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party debuted on October 31, 1995, it was a modest one-night-only affair. Compare that to the near month-long festivities we see today, and it’s clear that Disney’s approach to Halloween has evolved considerably.

A Not-So-Scary Beginning

I was fortunate enough to attend that very first MNSSHP back in 1995, along with my then 18-month-old daughter Alice and her mom, Michelle. Tickets were a mere $16.95 (I know, can you imagine?), and we pushed Alice around in her sturdy Emmaljunga stroller—Swedish-built and about the size of a small car. Cast Members, charmed by her cuteness, absolutely loaded us up with candy. By the end of the night, we had about 30 pounds of fun-sized candy bars, making that push up to the monorail a bit more challenging.

This Halloween event was Disney’s response to the growing popularity of Universal Studios Florida’s own Halloween hard ticket event, which started in 1991 as “Fright Nights” before being rebranded as “Halloween Horror Nights” the following year. Universal’s gamble on a horror-themed experience helped salvage what had been a shaky opening for their park, and by 1993, Halloween Horror Nights was a seven-night event, with ticket prices climbing as high as $35. Universal had stumbled upon a goldmine, and Disney took notice.

A Different Approach

Now, here’s where Disney’s unique strategy comes into play. While Universal embraced the gory, scare-filled world of horror, Disney knew that wasn’t their brand. Instead of competing directly with blood and jump-scares, Disney leaned into what they did best: creating magical, family-friendly experiences.

Thus, Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party was born. The focus was on fun and whimsy, not fear. Families could bring their small children without worrying about them being terrified by a chainsaw-wielding maniac around the next corner. This event wasn’t just a Halloween party—it was an extension of the Disney magic that guests had come to expect from the parks.

Disney had some experience with seasonal after-hours events, most notably Mickey’s Very Merry Christmas Party, which had started in 1983. But the Halloween party was different, as the Magic Kingdom wasn’t yet decked out in Halloween decor the way it is today. Disney had to create a spooky (but not too spooky) atmosphere using temporary props, fog machines, and, of course, lots of candy.

A key addition to that first event? The debut of the Headless Horseman, who made his eerie appearance in Liberty Square, riding a massive black Percheron. It wasn’t as elaborate as the Boo-to-You Parade we see today, but it marked the beginning of a beloved Disney Halloween tradition.

A Modest Start but a Big Future

That first MNSSHP in 1995 was seen as a trial run. As Disney World spokesman Greg Albrecht told the Orlando Sentinel, “If it’s successful, we’ll do it again.” And while attendance was sparse that night, there was clearly potential. By 1997, the event expanded to two nights, and by 1999, Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party had grown into a multi-night celebration with a full-fledged parade. Today, in 2024, it’s a staple of the fall season at Walt Disney World, offering 38 nights of trick-or-treating, character meet-and-greets, and special entertainment.

Universal’s Influence

It’s interesting to reflect on how Disney’s Halloween event might never have existed without the competition from Universal. Just as “The Wizarding World of Harry Potter” forced Disney to step up their game with “Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge,” Universal’s success with Halloween Horror Nights likely spurred Disney into action with MNSSHP. The friendly rivalry between the two parks has continually pushed both to offer more to their guests, and we’re all better off because of it.

So the next time you find yourself trick-or-treating through the Magic Kingdom, watching the Headless Horseman gallop by, or marveling at the seasonal fireworks, take a moment to appreciate how this delightful tradition came to be—all thanks to a little competition and Disney’s commitment to creating not-so-scary magic.

For more Disney history and behind-the-scenes stories, check out the latest episodes of the I Want That Too podcast on the Jim Hill Media network.

-

History10 months ago

History10 months agoThe Evolution and History of Mickey’s ToonTown

-

History11 months ago

History11 months agoUnpacking the History of the Pixar Place Hotel

-

History11 months ago

History11 months agoFrom Birthday Wishes to Toontown Dreams: How Toontown Came to Be

-

Film & Movies8 months ago

Film & Movies8 months agoHow Disney’s “Bambi” led to the creation of Smokey Bear

-

News & Press Releases10 months ago

News & Press Releases10 months agoNew Updates and Exclusive Content from Jim Hill Media: Disney, Universal, and More

-

Merchandise8 months ago

Merchandise8 months agoIntroducing “I Want That Too” – The Ultimate Disney Merchandise Podcast

-

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment3 months ago

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment3 months agoDisney’s Forgotten Halloween Event: The Original Little Monsters on Main Street

-

Film & Movies3 months ago

Film & Movies3 months agoHow “An American Tail” Led to Disney’s “Hocus Pocus”