Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment

To Hurl or Not to Hurl: A Second Opinion on “Mission: Space” — Part III

In the conclusion of his three part series, a slightly hungover Seth Kubersky braves Epcot’s newest thrill ride. Soooo … how did JHM’s newest columnist feel once he returned to Future World?

Okay. Let’s begin our pre-flight check:

Massively hyped new high-tech thrill attraction? Check.

Budget-limited underthemed queue line? Check.

Repeated apocalyptic safety warnings? Check.

Scientifically calibrated Jagermeister hangover? Check.

We have liftoff!

As the launch sequence of “Mission: Space” begins, you’re likely to think to yourself “hey, this isn’t so bad.” The initial acceleration is surprisingly gentle. If you are expecting an Incredible Hulk-like kick in the seat of the pants, you may at first find yourself wondering where the thrill is. But in a few seconds all such thoughts will be erased as you are gradually pinned to your seat by the mounting G-forces.

Here’s how to simulate the Mission: Space experience at home:

1) Find a cheap motel with a vibrating “magic fingers” bed.

2) Throw in some quarters and lie down flat on your back.

3) Have a large person (approx. 3 times your weight) slowly lie on your chest.

By the time the ride reaches full launch velocity, you will be the proud recipient of an instant facelift. The sensation of your skin being pulled tauter than Katherine Helmond’s in “Brazil” is unique and quite enjoyable. You will also feel the pressure in your throat and chest, and may briefly have difficulty swallowing. It is not, however, the “pit of your stomach” feeling that causes many people discomfort on roller coasters and freefall rides.

Despite my lingering hangover, I was suffering no real discomfort during the launch. No matter how many times I ride, this sequence remains a genuine rush. You get a sense of immense power and velocity without the violent shaking or spinning that comes with most thrill rides. The radius of the centrifuge is relatively large, and as the capsule is enclosed, so you have no external point of reference. Therefore, as long as you stay seated with your head back, you have no awareness that you are spinning.

At this point, I decided to push my science experiment to its logical conclusion. Even in my debilitated state, I was suffering no ill effects from the ride. But what if I ignored the safety instructions that they’d drilled into our heads? Was I truly willing to risk my life and health (and the clothing of my crewmates) in the name of science? You betcha!

Kids, don’t try this at home.

Do it at a friend’s house.

As the launch acceleration reached its peak, I lifted my head from the headrest. I leaned as far forward as the restraints would allow. And I swung my head from left to right, looking from side to side. Repeatedly. Exactly the way they tell you not to.

For a brief moment, this was almost a very bad idea. Tilting your head seems to make your inner ear instantly aware of the ride’s spinning. The sensation you experience doing this is immediate and powerful vertigo. Imagine sticking your head out the window of a speeding car, or leaning over the edge of a tall building. It’s a dizzying and disorienting experience. But it is not the thrill-ride equivalent of sticking your finger down your throat. I managed to lean back into my seat without doing the Technicolor yawn, and as soon as I did the vertigo disappeared.

As the blue sky beyond the cockpit dissolves into the blackness of space, you transition into the “zero-G” portion of the ride. For me, this is the most intriguing and most disappointing moment in the ride. Roller-coaster junkies know that high-G inversions and hairpins are fun, but airtime is life. We thrill for that brief moment of weightlessness you get cresting a hill. Rides like “Tower of Terror” and “Doctor Doom’s Fearfall” focus on giving us as much space between our butt and the seat as possible.

“Mission: Space” promised to raise the bar on airtime by giving us a few moments of “simulated” deep-space weightlessness. Instead, we get a bit of a cheat. What happens is that the centrifuge rapidly decelerates as the launch sequence ends. The massive pressure pinning you to your seat is released, and inertia pulls you slightly forward against the restraints. The psychological effect of this deceleration is a brief instant of a floating feeling. However, there is no genuine airtime, as your rear remains firmly attached to your seat. Perhaps if the cabin had been designed to invert you would get a truer sensation of weightlessness. I’m sure that would raise the upchuck factor by a power of 10, so we’ll just have to make do with what we get.

The moment of pseudo-zero-G is followed by the slingshot around the moon, which is nearly as intense as the launch. Then comes “hypersleep,” which is simply few seconds of quiet and darkness. Hypersleep is broken by sirens and flashing lights alerting you to an asteroid field. As the centrifuge accelerates the cabin pitches and rolls to simulate your ship swerving among the rocks. This sequence is about as dynamic as Star Tours, with the addition of G-forces less powerful than the launch. The movement, like everything in the ride, is smooth and well coordinated to the video. It is certainly less taxing than “Back to the Future” or “Body Wars.”

In the interest of scientific completeness, I repeated my head-leaning experiment during all the high-intensity segments of the ride. Again, you get a brief head-rush, but nothing as nauseating as the warnings might suggest. Try as I might, I was unable to give myself anything worse than a short spell of dizziness.

I should note that throughout the ride you will be asked to participate in the ride’s “interactive” feature. Each crewmember will have two tasks to perform. One of the two lights in front of you will light up, and Gary will tell you to push the button. If you do, there will be a brief sound effect. If not, a computer voice will announce a “computer override.” Either way, there will be absolutely no effect on your ride or its ending. You will get no particular praise or condemnation based on your performance. Every mission is successful, even if you deliberately fail in your button pushing. There isn’t even a score provided so that you can judge how well you did.

The final section of the ride begins with the decent into Mars’ atmosphere, similar to the launch and slingshot, followed by a gently swooping ride through the canals. Again, the movement is smoother and less jarring than most simulators. During this segment, you will be asked to grab the vibrating joystick (is that appropriate for a Disney ride?) and follow Gary’s instructions (“Left! Left! Pull up! Pull up!) Like the buttons, there is no punishment or reward for playing with your stick (yeah, that sounds pretty bad too). In fact, I’ve grown fond of pulling the stick in the opposite direction, just to see if I can cause a crash. No luck yet.

The ride ends in an all-too-familiar “near miss,” much like “Star Tours” and “Back to the Future.” You get a round of applause from Gary and his mission control cohorts. He invites you to proceed to the “advanced training lab,” and the screens slide back and the restraints release. Guests stumble out of their capsules and are herded down an unglamorous corridor towards the postshow area.

So, I survived. I determined, based on my non-double-blind single-sample experiment, that it is possible to ride “Mission: Space” while hung over without losing your lunch. The only close call came when I lifted my head from the headrest, and that discomfort was short-lived. My headache and stiff joints were still there, but the adrenaline rush of the ride was quite invigorating. Rather than feeling sick, I was ready to go another round.

At this point I conducted an unrepresentative, unscientific survey. Basically, I bugged every person coming off the ride to tell me how he or she felt. Reactions ranged from delight and enthusiasm to mild shakiness. Pre-teen kids seems the most excited, many bouncing up and down asking to go again. Their middle-aged soccer moms typically said “Once was enough,” but did it with a smile on their faces. I even saw a few grandparents who really seemed to get a kick out of the ride.

In several trips through the attraction, I only encountered one girl who did not enjoy her trip into space. She was a British tourist who was lined up in the pod next to mine. She was extremely nervous waiting for the ride, and the safety warnings seemed to agitate her more. It took constant reassurance from her family to get her into the capsule. Despite all this, she conceded that the ride was not as bad as a roller coaster, and she didn’t need to rush to the bathroom or collapse in the corner. I suspect a drink of water and a few minutes rest will cure the majority of ill effects caused by the ride.

I also cornered some ride attendants and quizzed them about the upchuck factor. All the CMs I asked said they’ve been averaging only one or two in-ride accidents per day. Some days go by with no puking whatsoever. This is comparable to other thrill rides and simulators. It is significantly less than the original version of “Body Wars,” which probably holds the title as Disney’s all-time vomit king.

As I said, this survey is based on too small a sample to be scientifically representative. But I expect these results to be consistent for most riders. Remember, your mileage may vary. If you are unusually susceptible to motion sickness, you probably won’t enjoy this ride. People with low blood pressure may have trouble handling the high G-forces (my ex-wife used to black out on the hairpin turns in “Kumba”). But if you can handle most simulators and modest coasters, you can probably handle “Mission: Space” just fine. Even people who typically don’t enjoy large coasters or rides like the Teacups might be surprised how well they can handle it. As long as you can remain calm and approach the experience with a positive, relaxed attitude, the ride should be well worth your time.

On my last trip though the attraction, I experienced the side effects of one of these rare ill guests. I was in the ready room, Gary had just finished his spiel on the overhead monitors, and we were waiting for the door to the curving corridor to open. After a few moments wait, the door behind us opened. A chipper CM informed us that due to “technical difficulties” we would be restaged in another ready room. One row at a time we were led across the room to the opposite ready room and lined back up on our numbers.

“Protein spill?” I asked.

“Yup, something like that,” the CM chuckled.

“How often do you have to do this?”

“First one today.”

Apparently, when there is a mishap they briefly shut down the affected bay for cleaning and restage the guests to another centrifuge. If the spill is minor they can clean it and get the bay ready by the next cycle. If there is a bigger mess, they can seal that particular capsule, allowing the rest of the cabins on that centrifuge to be used until there is time to disinfect. The cabin interiors are obviously designed to make this cleaning as efficient as possible.

Mission: Space Race, the centerpiece of the postshow,

brought to you by Chuck E. Cheese.

Once you’ve disembarked the ride and proceeded down the exit corridor, you arrive at the “Advanced Training Lab.” Remember Gary’s numerous mentions of the mission control training you will receive? See the colorful signs overhead advertising the “Mission: Space Race” experience that awaits? Expecting an interactive postshow on the scale of the classic Kodak ImageWorks, or Seabase Alpha? Or even the AT&T Global Village? Well, forget about it.

Instead, we get a modest-sized room with the aesthetic décor of your local mall’s video arcade. To the left is a Chuck E. Cheese-style gerbil maze for the kiddies, a simple “find the lost astronaut” video game that would get laughed off your Xbox, and a kiosk for sending email postcards. To the right is the centerpiece of the postshow, a large group game called “Mission: Space.” At the front of the room, 4 players per team play “pilots,” matching colored balls to “trouble spots” on a spaceship schematic. The rest of the team uses their “mission controller” computer consoles to generate the colored balls by pressing buttons.

C’mon kids, you can play your Playstation at home.

It’s like a very simple cross between Simon and Tetris, without being as much fun as either one. The results of the “race” are projected overhead. The results of the game are always suspiciously close, with both teams coming in within a point or two of each other every time. My personal best score as a “mission controller” is 24 points, but there isn’t enough replayability to make it worth waiting in line for more than once.

Beyond the disappointing postshow is the inevitable gift shop. In fact, the shop gets as much (if not slightly more) square footage as the postshow, which tells you something about Disney’s priorities these days. The good news is there isn’t much plush. The bad news is that the ride-specific merchandise is uninspiring, and much of the shelf space is taken up by junk that you can find in any mall.

Cheap crap! We gottcha cheap crap here!

So, what can we conclude from this rather long-winded tour of “Mission: Space?” What advice do I have for the weak of spirit (or stomach) who want to reach for the stars?

1) Relax. The ride is intense and unique, but it isn’t a medieval torture device. If you can handle most simulators and roller coasters, you can handle this. Even if the teacups make you toss your scones, you may be surprised at well you survive “Mission: Space.” Your own anxiousness is your worst enemy, so don’t get yourself too worked up over the safety warnings.

2) Keep your head back and your eyes front. Failure to do so isn’t a recipe for instant disaster, but it will make your head spin. As long as you stay properly seated, you won’t be aware of the spinning, only gravitational pressure, and you are unlikely to get disoriented.

3) Don’t sweat the button pushing. If you want to play along with the “interactive” element of the ride, go ahead. But if you don’t, you won’t be missing a thing. This isn’t “Men in Black;” there’s no such thing as a good or bad ending. If you are the kind of person who panics under pressure, and worries that you’re going to “fail” the ride, chill out and ignore Gary’s directives. It won’t make a bit of difference in the end.

4) Lower your expectations. If you are expecting a ride that blends the Disney tradition of seamless storytelling with amazing technology, you may be a bit let down when you only get half the equation. Instead, expect an amazing technological demonstration, with just enough theming to get the job done.

Disney took out a full-page advertisement (disguised as a news article) in this past Sunday’s Orlando Sentinel. In the ad, they repeatedly refer to “Mission: Space” as an “E-Ticket.” I have read other sources where they refer to it as the “first F-Ticket ride.”

The thrill of “Mission: Space” is genuine, intense, and original. It is something that you won’t find at your local Six Flags.

But, to my mind, it takes more than exceptional thrills to make an E-Ticket. It requires a great story that has a beginning, middle, and end. It requires attention to the small details that you only discover after dozens of rides. It requires an immersive environment that flows seamlessly from the queue to the preshow to the exit.

“Splash Mountain” is an E-Ticket. So is “Tower of Terror,” the last true E-Ticket thrill ride built at WDW. “Killamanjaro Safaris” is an E-Ticket, but a scenic one in the tradition of the “Jungle Cruise” rather than a thrill ride. “Spiderman” is certainly an E-Ticket, perhaps the first F-Ticket, but the “Hulk Coaster” is not, despite its impressive launch.

“Mission: Space,” by this standard, is not a full E-Ticket. Call it an E-Minus or D-Plus. A more consistent storyline, follow-through on the promised interactivity, and a better queue and postshow would push it over the top. Maybe if a clone is built in Tokyo they’ll give it the budget needed to use this amazing new technology to its fullest storytelling potential.

Until then, I’ll be happily getting my G-force fix, and bringing along something to read in the queue.

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment

Disney and Macy’s 90-Year Thanksgiving Day Parade Partnership: From Mickey’s First Balloon to Minnie’s Big Debut

Now, folks, if you’re like me, Thanksgiving just wouldn’t be the same without a coffee, a cozy seat, and Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade on the TV. And if you’re really like me, you’re watching for one thing: Disney balloons floating down 34th Street. Ever wondered how Mickey, Donald, and soon Minnie Mouse found their way into this beloved New York tradition? Well, grab your popcorn because we’re diving into nearly 90 years of Disney’s partnership with Macy’s.

The Very First Parade and the Early Days of Balloons

The Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade goes way back to 1924, but if you can believe it, balloons weren’t part of the festivities until 1927. That first lineup included Felix the Cat, a dragon, and a toy soldier, all towering above the crowds. Back then, Macy’s had a pretty wild idea to end the parade: they would let the balloons drift off into the sky, free as birds. But this wasn’t just Macy’s feeling generous. Each balloon had a message attached, offering a $100 reward (about $1,800 in today’s dollars) for anyone who returned it to the flagship store on 34th Street.

And here’s where it gets interesting. This tradition carried on for a few years, right up until 1932, when Felix the Cat almost took down a plane flying over New York City! Imagine that—you’re flying into LaGuardia, and suddenly, there’s a 60-foot balloon drifting toward your wing. Needless to say, that was the end of Macy’s “fly away” stunt, and from then on, the balloons have stayed firmly grounded after the parade ends.

1934: Mickey Mouse Floats In, and Disney Joins the Parade

It was 1934 when Mickey Mouse finally made his grand debut in the Macy’s parade. Rumor has it Walt Disney himself collaborated with Macy’s on the design, and by today’s standards, that first Mickey balloon was a bit of a rough cut. This early Mickey had a hotdog-shaped body, and those oversized ears gave him a slightly lopsided look. But no one seemed to mind. Mickey was there, larger than life, floating down the streets of New York, and the crowd loved him.

Mickey wasn’t alone that year. He was joined by Pluto, Horace Horsecollar, and even the Big Bad Wolf and Practical Pig from The Three Little Pigs, making it a full Disney lineup for the first time. Back then, Disney wasn’t yet the entertainment powerhouse we know today, so for Walt, getting these characters in the parade meant making a deal. Macy’s required its star logo to be featured on each Disney balloon—a small concession that set the stage for Disney’s long-standing presence in the parade.

Duck Joins and Towers Over Mickey

A year later, in 1935, Macy’s introduced Donald Duck to the lineup, and here’s where things got interesting. Mickey may have been the first Disney character to float through the parade, but Donald made a huge splash—literally. His balloon was an enormous 60 feet tall and 65 feet long, towering over Mickey’s 40-foot frame. Donald quickly became a fan favorite, appearing in the lineup for several years before being retired.

Fast-forward a few decades, and Donald was back for a special appearance in 1984 to celebrate his 50th birthday. Macy’s dug the balloon out of storage, re-inflated it, and sent Donald down 34th Street once again, bringing a bit of nostalgia to the holiday crowd.

A Somber Parade in 2001

Now, one of my most memorable trips to the parade was in 2001, just weeks after the 9/11 attacks. Nancy and I, along with our friends, headed down to New York, and the mood was something I’ll never forget. We watched the start of the parade from Central Park West, but before that, we went to the Museum of Natural History the night before to see the balloons being inflated. They were covered in massive cargo nets, with sandbags holding them down. It’s surreal to see these enormous balloons anchored down before they’re set free.

That year, security was intense, with police lining the streets, and then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani rode on the Big Apple float to roaring applause. People cheered his name, waving and shouting as he passed. It felt like the entire city had turned out to show their resilience. Even amidst all the heightened security and tension, seeing those balloons—brought a bit of joy back to the city.

Balloon Prep: From New Jersey’s MetLife Stadium to California’s D23 Expo

Each year before the parade, Macy’s holds a rehearsal event known as Balloon Fest at MetLife Stadium in New Jersey. This is where handlers get their first crack at guiding the balloons, practicing with their parade masters, and learning the ropes—literally. It’s an entire production unto itself, with dozens of people rehearsing to make sure these enormous inflatables glide smoothly down the streets of New York on parade day.

In 2015, Macy’s took the balloon show on the road, bringing their Buzz Lightyear balloon out to California for the D23 Expo. I was lucky enough to be there, and watching Buzz get inflated piece by piece in the Anaheim Convention Center parking lot was something to behold. Each section was filled with helium in stages, and when they got around to Buzz’s lower half, well, there were more than a few gas-related jokes from the crowd.

These balloons seem to have a personality all their own, and seeing one like Buzz come to life up close—even outside of New York—had all the excitement and anticipation of the real deal.

Mickey’s Comeback as a Bandleader and Sailor Mickey

After a long hiatus, Mickey Mouse made his return to the Macy’s parade in 2000, this time sporting a new bandleader outfit. Nine years later, in 2009, Sailor Mickey joined the lineup, promoting Disney Cruise Line with a nautical twist. Over the past two decades, Disney has continued to enchant parade-goers with characters like Buzz Lightyear in 2008 and Olaf from Frozen in 2017. These balloons keep Disney’s iconic characters front and center, drawing in both longtime fans and new viewers.

But ever wonder what happens to the balloons after they reach the end of 34th Street? They don’t just disappear. Each balloon is carefully deflated, rolled up like a massive piece of laundry, and packed into storage bins. From there, they’re carted back through the Lincoln Tunnel to Macy’s Parade Studio in New Jersey, where they await their next flight.

Macy’s Disney Celebration at Hollywood Studios

In 1992, Macy’s took the spirit of the parade down to Disney-MGM Studios in Orlando. After that year’s parade, several balloons—including Santa Goofy, Kermit the Frog, and Betty Boop—were transported to Hollywood Studios, re-inflated, and anchored along New York Street as part of a holiday display. Visitors could walk through this “Macy’s New York Christmas” setup and see the balloons up close, right in the middle of the park. While this display only ran for one season, it paved the way for the Osborne Family Spectacle of Dancing Lights, which became a holiday staple at the park for years to come.

Minnie Mouse’s Long-Awaited Debut in 2024

This year, Minnie Mouse will finally join the parade, making her long-overdue debut. Macy’s is rolling out the red carpet for Minnie’s arrival with special pop-up shops across the country, where fans can find exclusive Minnie ears, blown-glass ornaments, T-shirts, and more to celebrate her first appearance in the Thanksgiving Day Parade.

For those lucky enough to catch the parade this year, you’ll see Minnie take her first float down 34th Street, decked out in her iconic red bow and polka-dot dress. Macy’s and Disney are also unveiling a new Disney Cruise Line float honoring all eight ships, including the latest, the Disney Treasure.

As always, I’ll be watching from my favorite chair, coffee in hand, as Minnie makes her grand entrance. The 98th annual Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade airs live on NBC, and it’s a tradition you won’t want to miss—whether you’re on 34th Street or tuning in from home.

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment

Disney’s Forgotten Halloween Event: The Original Little Monsters on Main Street

When most Disney fans think of Halloween in the parks, they immediately picture Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party at Walt Disney World or the Oogie Boogie Bash at Disneyland Resort. But before those events took over as the must-attend spooky celebrations, there was a little-known event at Disneyland called Little Monsters on Main Street. And its origins? Well, they go all the way back to the 1980s, during a time when America was gripped by fear—the Satanic Panic.

You see, back in the mid-1980s, parents were terrified that Halloween had become dangerous. Urban legends about drug-laced candy or razor blades hidden in apples were widespread, and many parents felt they couldn’t let their kids out of sight for even a moment. Halloween, which was once a carefree evening of trick-or-treating in the neighborhood, had suddenly become a night filled with anxiety.

This is where Disneyland’s Little Monsters on Main Street came in.

The Origins of Little Monsters on Main Street

Back in 1989, the Disneyland Community Action Team—later known as the VoluntEARS—decided to create a safe, nostalgic Halloween experience for Cast Members and their families. Many schools in the Anaheim area were struggling to provide basic school supplies to students, and the VoluntEARS saw an opportunity to combine a safe Halloween with a charitable cause. Thus, Little Monsters on Main Street was born.

This event was not open to the general public. Only Disneyland Cast Members could purchase tickets, which were initially priced at just $5 each. Cast Members could bring their kids—but only as many as were listed as dependents with HR. And even then, the park put a cap on attendance: the first event was limited to just 1,000 children.

A Unique Halloween Experience

Little Monsters on Main Street wasn’t just another Halloween party. It was designed to give kids a safe, fun environment to enjoy trick-or-treating, much like the good old days. On Halloween night in 1989, kids in costume wandered through Disneyland with their pillowcases, visiting 20 different trick-or-treat stations. They also had the chance to ride a few of their favorite Fantasyland attractions, all after the park had closed to the general public.

The event was run entirely by the VoluntEARS—about 200 of them—who built and set up all the trick-or-treat stations themselves. They arrived at Disneyland before the park closed and, as soon as the last guest exited, they began setting up stations across Main Street, Adventureland, Frontierland, Fantasyland, and Tomorrowland. The event ran from 7:30 to 9:30 p.m., and by the time the last pillowcase-wielding kid left, the VoluntEARS cleaned everything up, making sure the park was ready for the next day’s operations.

It wasn’t just candy and rides, though. The event featured unique entertainment, like a Masquerade Parade down Main Street, U.S.A., where kids could show off their costumes. And get this—Disneyland even rigged up a Cast Member dressed as a witch to fly from the top of the Matterhorn to Frontierland on the same wire that Tinker Bell uses during the fireworks. Talk about a magical Halloween experience!

The Haunted Mansion “Tip-Toe” Tour

Perhaps one of the most memorable parts of Little Monsters on Main Street was the special “tip-toe tour” of the Haunted Mansion. Now, Disneyland’s Haunted Mansion can be a pretty scary attraction for younger kids, so during this event, Disney left the doors to the Stretching Room and Portrait Gallery wide open. This allowed kids to walk through and peek at the Haunted Mansion’s spooky interiors without actually having to board the Doom Buggies. For those brave enough to ride, they could, of course, take the full trip through the Haunted Mansion—or they could take the “chicken exit” and leave, no harm done.

Growing Success and a Bigger Event

Thanks to the event’s early success, Little Monsters on Main Street grew in size. By 1991, the attendance cap had been raised to 2,000 kids, and Disneyland added more activities like magic shows and hayrides. They also extended the event’s hours, allowing kids to enjoy the festivities until 10:30 p.m.

In 2002, the event moved over to Disney California Adventure, where it could accommodate even more kids—up to 5,000 in its later years. The name was also shortened to just Little Monsters, since it was no longer held on Main Street. This safe, family-friendly Halloween event continued for several more years, with the last mention of Little Monsters appearing in the Disneyland employee newsletter in 2008. Though some Cast Members recall the event continuing until 2012, it eventually made way for Disney’s more public-facing Halloween events.

From Little Monsters to Mickey’s Not-So-Scary and Oogie Boogie Bash

Starting in the early 2000s, Disney began realizing the potential of Halloween-themed after-hours events for the general public. These early versions of Mickey’s Halloween Party and Mickey’s Halloween Treat eventually evolved into today’s Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party and Oogie Boogie Bash. Unfortunately, this also marked the end of the intimate, Cast Member-exclusive Little Monsters event, but it paved the way for the large-scale Halloween celebrations we know and love today.

While it’s bittersweet to see Little Monsters on Main Street fade into Disney history, its legacy lives on through these modern Halloween parties. And even though Cast Members now receive discounted tickets to Mickey’s Not-So-Scary and Oogie Boogie Bash, the special charm of an event created specifically for Disney’s employees and their families remains something worth remembering.

The Merch: A Piece of Little Monsters History

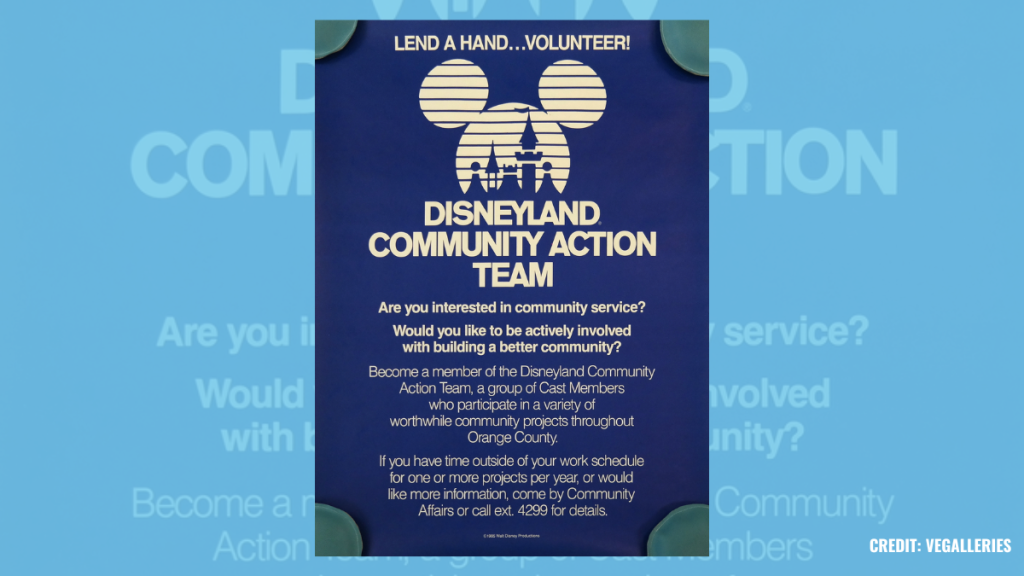

For Disney collectors, the exclusive merchandise created for Little Monsters on Main Street is still out there. You can find pins, name tags, and themed pillowcases on sites like eBay. One of the coolest collectibles is a 1997 cloisonné pin set featuring Huey, Dewey, and Louie dressed as characters from Hercules. Other sets paid tribute to the Main Street Electrical Parade and Pocahontas, while the pillowcases were uniquely designed for each year of the event.

While Little Monsters on Main Street may be gone, it’s a fascinating piece of Disneyland history that played a huge role in shaping the Halloween celebrations we enjoy at Disney parks today.

Want to hear more behind-the-scenes stories like this? Be sure to check out I Want That Too, where Lauren and I dive deep into the history behind Disney’s most beloved attractions, events, and of course, merchandise!

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment

The Story of Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party: From One Night to a Halloween Family Tradition

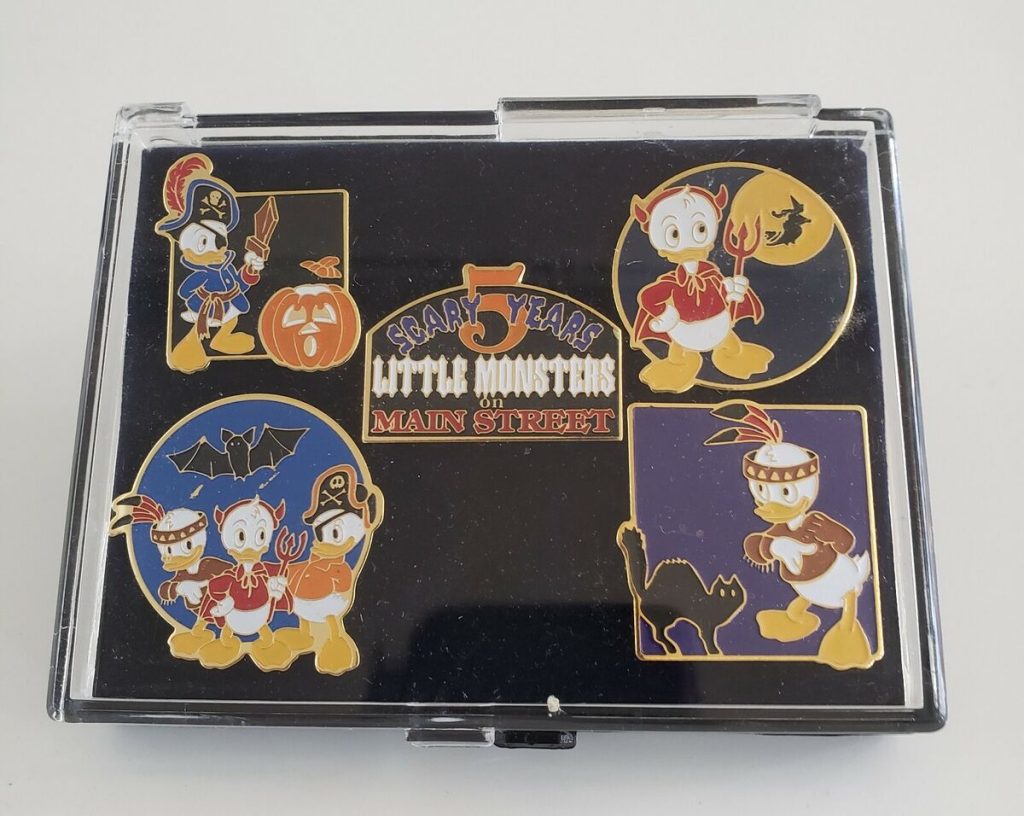

The spooky season is already in full swing at Disney parks on both coasts. On August 9th, the first of 38 Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party (MNSSHP) nights for 2024 kicked off at Florida’s Magic Kingdom. Meanwhile, over at Disney California Adventure, the Oogie Boogie Bash began on August 23rd and is completely sold out across its 27 dates this year.

Looking back, it’s incredible to think about how these Halloween-themed events have grown. But for Disney, the idea of charging guests for Halloween fun wasn’t always a given. In fact, when the very first Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party debuted on October 31, 1995, it was a modest one-night-only affair. Compare that to the near month-long festivities we see today, and it’s clear that Disney’s approach to Halloween has evolved considerably.

A Not-So-Scary Beginning

I was fortunate enough to attend that very first MNSSHP back in 1995, along with my then 18-month-old daughter Alice and her mom, Michelle. Tickets were a mere $16.95 (I know, can you imagine?), and we pushed Alice around in her sturdy Emmaljunga stroller—Swedish-built and about the size of a small car. Cast Members, charmed by her cuteness, absolutely loaded us up with candy. By the end of the night, we had about 30 pounds of fun-sized candy bars, making that push up to the monorail a bit more challenging.

This Halloween event was Disney’s response to the growing popularity of Universal Studios Florida’s own Halloween hard ticket event, which started in 1991 as “Fright Nights” before being rebranded as “Halloween Horror Nights” the following year. Universal’s gamble on a horror-themed experience helped salvage what had been a shaky opening for their park, and by 1993, Halloween Horror Nights was a seven-night event, with ticket prices climbing as high as $35. Universal had stumbled upon a goldmine, and Disney took notice.

A Different Approach

Now, here’s where Disney’s unique strategy comes into play. While Universal embraced the gory, scare-filled world of horror, Disney knew that wasn’t their brand. Instead of competing directly with blood and jump-scares, Disney leaned into what they did best: creating magical, family-friendly experiences.

Thus, Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party was born. The focus was on fun and whimsy, not fear. Families could bring their small children without worrying about them being terrified by a chainsaw-wielding maniac around the next corner. This event wasn’t just a Halloween party—it was an extension of the Disney magic that guests had come to expect from the parks.

Disney had some experience with seasonal after-hours events, most notably Mickey’s Very Merry Christmas Party, which had started in 1983. But the Halloween party was different, as the Magic Kingdom wasn’t yet decked out in Halloween decor the way it is today. Disney had to create a spooky (but not too spooky) atmosphere using temporary props, fog machines, and, of course, lots of candy.

A key addition to that first event? The debut of the Headless Horseman, who made his eerie appearance in Liberty Square, riding a massive black Percheron. It wasn’t as elaborate as the Boo-to-You Parade we see today, but it marked the beginning of a beloved Disney Halloween tradition.

A Modest Start but a Big Future

That first MNSSHP in 1995 was seen as a trial run. As Disney World spokesman Greg Albrecht told the Orlando Sentinel, “If it’s successful, we’ll do it again.” And while attendance was sparse that night, there was clearly potential. By 1997, the event expanded to two nights, and by 1999, Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party had grown into a multi-night celebration with a full-fledged parade. Today, in 2024, it’s a staple of the fall season at Walt Disney World, offering 38 nights of trick-or-treating, character meet-and-greets, and special entertainment.

Universal’s Influence

It’s interesting to reflect on how Disney’s Halloween event might never have existed without the competition from Universal. Just as “The Wizarding World of Harry Potter” forced Disney to step up their game with “Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge,” Universal’s success with Halloween Horror Nights likely spurred Disney into action with MNSSHP. The friendly rivalry between the two parks has continually pushed both to offer more to their guests, and we’re all better off because of it.

So the next time you find yourself trick-or-treating through the Magic Kingdom, watching the Headless Horseman gallop by, or marveling at the seasonal fireworks, take a moment to appreciate how this delightful tradition came to be—all thanks to a little competition and Disney’s commitment to creating not-so-scary magic.

For more Disney history and behind-the-scenes stories, check out the latest episodes of the I Want That Too podcast on the Jim Hill Media network.

-

History10 months ago

History10 months agoThe Evolution and History of Mickey’s ToonTown

-

History11 months ago

History11 months agoUnpacking the History of the Pixar Place Hotel

-

History11 months ago

History11 months agoFrom Birthday Wishes to Toontown Dreams: How Toontown Came to Be

-

Film & Movies8 months ago

Film & Movies8 months agoHow Disney’s “Bambi” led to the creation of Smokey Bear

-

News & Press Releases10 months ago

News & Press Releases10 months agoNew Updates and Exclusive Content from Jim Hill Media: Disney, Universal, and More

-

Merchandise8 months ago

Merchandise8 months agoIntroducing “I Want That Too” – The Ultimate Disney Merchandise Podcast

-

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment3 months ago

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment3 months agoDisney’s Forgotten Halloween Event: The Original Little Monsters on Main Street

-

Film & Movies3 months ago

Film & Movies3 months agoHow “An American Tail” Led to Disney’s “Hocus Pocus”