General

Walt Disney remembers his studio’s “Growing Pains”

Following up on yesterday’s JHM article, Wade Sampson shares an old magazine article where the “Old Mousetro” recalls all the extra effort involved with turning Disney Studios from an outfit that made animated shorts to a company that made full-length animated features.

The following is an excerpt from an article entitled “Growing Pains.” In which Walt Disney (circa December of 1940) recalls what it took to make his tiny little studio into the Hollywood powerhouse that WDS was just prior to the start of WWII:

|

Advertisement |

My business has been a thrilling adventure, an unending voyage of discovery and exploration in the realms of color, sound, and motion.

And it has been a lot of fun and a lot of headache. The suspense has been continuous and sometimes awful. In fact, life might seem rather dull without our annual crisis. But after all, it is stress and challenge and necessity that make an artist grow and outdo himself. My men have had plenty of all three to keep them on their toes. But how very fortunate we are, as artists, to have a medium whose potential limits are still far off in the future; a medium of entertainment where, theoretically at least, the only limit is the imagination of the artist. As for the past, the only important conclusions that I can draw from it are that the public will pay for quality, and the unseen future will take care of itself if one just keeps growing up a little every day.

The span of twelve years between ‘Steamboat Willie’, the first Mickey with sound, and ‘Fantasia’, is the bridge between primitive and modern animated pictures. No genius built this bridge. It was built by hard work and enthusiasm, integrity of purpose, a devotion to our medium, confidence in its future, and, above all, by a steady day-by-day growth in which we all simply studied our trade and learned.

I came to Hollywood broke in 1923, and my brother Roy staked me to a couple of hundred. We lived in one room and Roy did the cooking. He was my business manager, and I didn’t have any business. His job was to scare up three meals a day, and his job now is to conjure up three million dollars to meet the annual payroll. Both jobs have demanded just about the same amount of sweat, ingenuity, and magic. The main difference is that Roy sweats more red ink now. But no matter what the future deals me, I shall consider that I have come a long way, if for no other reason that that Roy doesn’t do the cooking any more.

I sold my first animated cartoon for thirty cents a foot. ‘Pinocchio’ and ‘Fantasia’ cost around three hundred dollars a foot. The first Mickey Mouse was made by twelve people after hours in a garage. About twelve hundred people are working overtime now in a fifty-one-acre plant with fourteen buildings, four restaurants, its own water system, air-conditioning, and a gentleman named Myron to massage the kinks out of my neck.

My first motion picture camera was ‘ad libbed’ out of spare parts and a drygoods box swiped from an alley off Hollywood Boulevard. It was hand-cranked, the camera. Even then I felt the urge to grow, to expand-I was very ambitious in those days-so we bought a used motor for a dollar to run the camera. It had once been a second-hand motor, but since that time it had seen everything and died. We had to hire a technician to make it go. We have been hiring technicians ever since. Our business has grown with and by technical achievements. Should this technical progress ever come to a full stop, prepare the funeral oration for our medium. That is how dependent we artists have become on the new tools and refinements which the technicians give us. Sound, Technicolor, the multiplane camera, Fantasound, these and a host of other less spectacular contributions have been added to the artist’s tools, and have made possible the pictures which are the milestones in our progress.

That first movie camera now stands in all its ad lib splendor in a Los Angeles Museum. Our new multiplane cameras are two stories high and operate by remote control. But, on the whole, the basic tools and techniques of my craft had been worked out before I learned the rudiments of animation out of a book in Kansas City.

There had been animated cartoons long before motion pictures. The Stone Age artist came pretty close to animation when he drew several sets of legs on his animals, each set showing a different stage of a single movement. A Frenchman named Plateau was the first to make a cartoon move. In 1831, he invented the phenakistoscope, a device of moving disks and peepholes. The successive stages of an action were drawn on one disk. When the disk was spun, the illusion of motions resulted. Many similar devices were invented to make pictures move. The first animated cartoon on motion picture film was made by J. Stuart Blackton in 1906. It showed a fellow blowing smoke in the face of his girl friend. A bit corny, but not bad! ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs’ was not the first feature-length cartoon by twenty years, while the first cartoon mechanically colored dates back to 1919. The greatest single contribution of the pioneers came from Earl Hurd who invented (1915) the idea of tracing the moving parts of a cartoon on celluloids superimposed over opaque backgrounds. This great labor-saving device is still the foundation of our modern method.

The miracle of seeing drawings move was enough to enthrall the early motion picture audiences. Then, as the edge of the miracle wore off, interest in cartoons was revived by numerous series of cartoon built around the antics of stock characters. Some of these series were very popular. Whether or not these pre-Mickey cartoonists ever sat back and thought about the possibilities in the medium, I don’t know. I was ambitious and wanted to make better pictures, but the length of my foresight is measured by this admission: Even as late as 1930, my ambition was to be able to make cartoons as good as the Aesop’s Fables series.

I was knocking out a series called ‘Oswald the Lucky Rabbit’ for Universal at the time sound exploded like a bomb under silent pictures. The series was going over. We had built up a little organization. Roy and I each had our own homes and a ‘flivver.’ We had money in the bank and security. But we didn’t like the looks of the future. The cartoon business didn’t seem to be going anywhere except in circles. The pictures were kicked out in a hurry and made to a price. Money was the only object. Cartoons had become the shabby Cinderella of the picture industry.

They were thrown in for nothing as a bonus to exhibitors buying features. I resented that. Some of the possibilities in the cartoon medium had begun to dawn on me. And at the same time we saw that the medium was dying. You could feel rigor mortis setting in. I could feel it in myself. Yet with more money and time, I felt we could make better pictures and shake ourselves out of the rut. When our distributor, Universal, wouldn’t give us the money, we quit. Most of our staff went over to Universal. That hurt! But I had made my Declaration of Independence and traded security for self-respect. An artist who wouldn’t is a dead mackerel. Thereafter, we were to make pictures for quality and not for price. The public has been willing to pay for this quality.

Out on my own again, I looked for a new character and hit on Mickey Mouse. The first two Mickey Mouse pictures were silent. We couldn’t peddle them. It occurred to me that in a world gone sound-mad, since the release of Al Jolson’s ‘The Jazz Singer’, a cartoon with action synchronized to sound would be something of a sensation. My third Mickey, ‘Steamboat Willie’, was planned with this in mind. By some miracle we managed to figure out the basic method for synchronizing sound and action that we still use. When the picture was half finished, we had a showing with sound. A couple of my boys could read music and one of them could play a mouth organ. We put them in a room where they could not see the screen and arranged to pipe their sound into the room where our wives and friends were going to see the picture. The boys worked from a music and sound-effects score. After several false starts, sound and action got off with the gun. The mouth-organist played the tune, the rest of us in the sound department bammed tin pans and blew slide whistles on the beat. The synchronism was pretty close. The effect on our little audience was nothing less than electric. They responded almost instinctively to this union of sound and motion. I thought they were kidding me. So they put me in the audience and ran the action again. It was terrible, but it was wonderful! And it was something new!

I took ‘Steamboat Willie’ to New York and started a dreary hunt for a sound company which was not too busy or too expensive to record the sound for me. I finally made a deal with Cinephone. Theirs was a pretty punk sound system until Bill Garity redesigned it later on. But in spite of that, ‘Steamboat Willie’ was an instant hit. It played the Colony, then moved to Roxy’s. Mickey was a big shot overnight. Lush offers poured in from Hollywood, but Cinephone had us nailed to the contract. Cinephone had given me a bigger picture budget that had Universal, and Columbia had upped the figure considerably again. But soon the increasing quality on which we were building our business demanded bigger and bigger advances. Columbia couldn’t take it, so in 1931, we made a deal with United Artists to distribute our cartoons.

This new deal, for all practical purposes, gave us financial independence. Since then, we alone have determined how much our pictures will cost. Not that the industry hasn’t had a great deal to say about our picture costs, in one sense. Time and again, it has been said that were crazy and would go broke. Mack Sennett claimed that we put live-action shorts out of business because they could not afford to spend the money to compete with us. The fact was the reverse. Live-action shorts could not afford not to spend more money if it would improve their quality. By 1931, production costs had risen from $5400 to $13,500 per cartoon. This was an unheard of and outrageous thing, it seemed.

And a year later, when we turned down Carl Laemmle’s offer to advance us $15,000 on each picture, he told me quite frankly that I was headed for bankruptcy. This was not short-sighted on his part. He had no way of seeing what we saw in the future of the medium.

As Mickey Mouse became a universal favorite and the money rolled in, we had been able to afford the time and money to analyze our craft. I think it is astounding that we were the first group of animators, so far as I can learn, who ever had the chance to study their own work and correct its errors before it reached the screen. In our little studio on Hyperion Street, every foot of rough animation was projected on the screen for analysis, and every foot was drawn and redrawn until we could say, “This is the best that we can do.” We had become perfectionists, and as nothing is ever perfect in this business, we were continually dissatisfied.

In fact, our studio had become more like a school than a business. As a result, our characters were beginning to act and behave in general like real persons. Because of this we could begin to put real feeling and charm in our characterization. After all, you can’t expect charm from animated sticks, and that’s about what Mickey Mouse was in his first pictures. We were growing as craftsmen, through study, self-criticism, and experiment. In this way, the inherent possibilities in our medium were dug into and brought to light.

Each year we could handle a wider range of story material, attempt things we would not have dreamed of tackling the year before. I claim that this is not genius or even remarkable. It is the way men build a sound business of any kind-sweat, intelligence, and love of the job. Viewed in this light of steady, intelligent growth, there is nothing remarkable about the ‘Three Little Pigs’ or even ‘Fantasia’-they become inevitable.

The Silly Symphony series was launched in 1929. In Mickey Mouse cartoons, we kidded the modern scene. The material was limited. We wanted a series which would let us go in for more of the fantastic and fabulous and lyric stuff. The Silly Symphony didn’t give Mickey much competition until we added Technicolor in 1932. We thought that color would be worth the heavy extra cost. Color was part of life. A black-and-white print looked as drab alongside ‘Flowers and Trees’, as a gray day alongside a rainbow. We could do things with color! We could do many things with color that no other medium could do.

I remember Roy coming into the office about this time with a bunch of figures in one hand and eyes full of patient resignation. “How come,” began Roy, “How come that last year with thirty men we made thirty pictures, and this year with over a hundred and fifty, you get out only eighteen?” I can’t answer that type of question, but the surest way to take Roy’s mind off past and present troubles is to tell him that we need a lot more money in the immediate future. Roy has the greatest confidence in me, in our medium and in our future, but he is a business man and doesn’t like to live dangerously twelve months out of the year. In this instance, three little pigs and a big, bad wolf were soon to bring him days of peace-not many days, but a few.

‘The Three Little Pigs’ was released in 1933. It caused no excitement at its Radio City premiere. In fact, many critics preferred ‘Noah’s Ark’ which was released about the same time. I was told that some exhibitors and even United Artists considered The Pigs a ‘cheater’ because it had only four characters in it. The picture bounced back to fame from the neighborhood theaters. Possibly more people have seen ‘The Pigs’ than any other picture, long or short, ever made. So you get an insight into the short-subject business when I tell you that ‘The Pigs’ grossed only $125,000 its first year. ‘Snow White’ grossed over seven million. That’s the difference between shorts and features from the profit angle. The low rentals for short subjects have been a chronic headache for us. Our only solution has been to build our prestige through quality to the point where public demand forced the exhibitor to pay more for our product. Theaters paying two or three thousand a week for a feature may pay us only a hundred or a hundred and fifty dollars for a short. Gentlemen, I ask for justice.

Whatever the reason for The Pigs’ astonishing popularity, it was an important landmark in our growth. It nailed our prestige way up there. It brought us honors and recognition all over the world and turned the attention of young artists and distinguished older artists to our medium as a worthwhile outlet for their talents. We needed these men for future growth, and they came from all over the country to join our staff and be trained in our ways.

The success of the ‘Three Pigs’ was felt throughout our entire business. The income from all our pictures and from merchandising royalties took a sharp up-swing. The magazine ‘Fortune’ declared that our net profit for 1934 was $600,000 and I’ll take their word for it. That’s chickenfeed in Hollywood, but we are strictly small fry. We poured the money back into the business in a long-range expansion program pointing at feature-length production and the protection of our new prestige through constantly increasing quality. The Mickeys went Technicolor. We enlarged our training school and began a nation-wide advertising campaign for young artists.

The production costs on our Symphonies shot skyward until some of the little pictures approached the ridiculous figure of $100,000. But the quality was there, and by 1935 even the ‘Three Little Pigs’ looked dated and a bit shabby in comparison with the newer Symphonies. Our staff at this time numbered around three hundred. A greater degree of specialization was setting in. The plant was becoming more like a Ford factory, but our moving parts were more complex than cogs-human beings, each with his own temperament and values who must be weighed and fitted into his proper place. I think I was learning a great deal about handling men; or perhaps the men were learning how to handle me. But let me tell you this-young artists are just as reasonable and easy to handle as anybody else. Our temperament goes into our job.

We had our technique well in hand. We had learned how to use our tools and how to make our characters act convincingly. We had learned a lot about staging and camera angles. We knew something about timing and tempo. But a good story idea, in our business, is an imponderable thing. It seems to be largely made up of luck and inspiration. It must be exceedingly simple to be told in seven or eight hundred feet. It must, above all, have that elusive quality called charm. It must be unsophisticated, universal in its appeal and a lot of other things you can’t nail down in words but can only feel intuitively.

‘The Three Little Pigs’, ‘The Flying Mouse’, and ‘The Grasshopper and The Ants’, were examples of good stories. I used to feel at times that there wasn’t another good story idea left in the world which could be told in eight hundred feet. The length limitation of the Symphony became more and more galling. We were batting story ideas around for months and sometimes years trying to get the certain twist, the lacking element, or whatever the idea needed to make it a good story. Our files were filled with abandoned stories on which we had spent thousands. It was inevitable that we should go into feature-length pictures if only for the unlimited new story material this field held for us.

I thought we could make ‘Snow White’ for around $250,000. At least that’s what I told Roy. The figure didn’t make sense because we were spending about that much on every three Symphonies or 2500 feet of picture. Roy was very brave until the costs passed a million. He wasn’t used to figures of over a hundred thousand at that time. The extra cipher threw him. When costs passed the one and one-half million mark, Roy didn’t even bat an eye. He couldn’t; he was paralyzed. And I didn’t feel very full-blooded, either. We considered changing the name of the picture from ‘Snow White’ to ‘Frankenstein’. I believe that the final figure, including prints, exploitation, etc., was around two million.

We sort of half-way explained this to everybody by charging a million of it off to research and development. You know, building toward the future. And this was true, although we hadn’t exactly planned it to be that way. Webster sums up the spirit of the ‘Snow White’ enterprise in his definition of adventure at the beginning of this article-“risk, jeopardy; encountering of hazardous enterprise; a daring feat; a bold undertaking in which the issue hangs on unforeseen events, etc.”

As a matter of fact, we were practically forced into the feature field. We not only had to have its new story material, but also we had to have feature profits to justify our continuing expansion, and we sensed that we had gone about as far as we could in the short-subject field without getting ourselves in a rut. We needed this new adventure, this ‘kick in the pants,’ to jar loose some new enthusiasm and inspiration.

Research and preliminary work in a small way had begun on ‘Snow White’ as early as 1934. I picked that story because it was well known and I knew we could do something with seven ‘screwy’ dwarfs. Beyond that, we didn’t know exactly where we were going, but we were on our way. The picture was released at the turn of the year, 1937-38. At the end of its first year, ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs’ was reported to be the biggest money-maker of all times. It at least settled the question as to whether or not an audience could or would sit through an hour and thirty minutes of animated pictures. Most of the bets were that an audience would go blind. As a matter of fact, that question had been settled as early as 1935, when European audiences lined up in long queues to see a two-hour bill of our shorts. This bill ran for seventeen weeks in Stockholm, and similar all-cartoon bills have been quite successful in this country.

At the time of ‘Snow White’s’ release, our staff had grown to about six hundred. Having committed ourselves to a program of both features and shorts, it became necessary again to expand drastically. An additional eight hundred people were added to our payrolls in the next two years. For more studio space, we were forced to lease a row of apartment houses adjoining the studio, and other temporary buildings were erected on the lot. We needed a new studio and in a hurry. Not only did we need more space and more building, but the increasing emphasis on the technical side of our craft demanded the most modern and specially designed type of building and equipment. The new plant was started in 1939 on fifty-one acres near the Los Angeles River in Burbank. We moved in around the first of 1940.

The two years between ‘Snow White’ and ‘Pinocchio’ were years of confusion, swift expansion, reorganization. Hundreds of young people were being trained and fitted into a machine for the manufacture of entertainment which had become bewilderingly complex. And this machine had been redesigned almost overnight from one for turning out short subjects into one aimed mainly at increased feature production.

Produced under such conditions and forced to bear its share of this tremendously increased overhead during a two-year period, ‘Pinocchio’ is yet to return its original investment. It has been called a flop. Actually it was the second biggest box-office attraction of the year. ‘Gone with the Wind’ was first. ‘Pinocchio’ might have lacked ‘Snow White’s’ heart appeal, but technically and artistically it was superior. It indicated that we had grown considerably as craftsmen as well as having grown big in plant and numbers, a growth that is only important in proportion to the quality it adds to our product in the long run.

The large profits from ‘Snow White’, short subjects, and the mounting royalties from our merchandising enterprises, had all gone back into the business to pay for the new studio and expansion program. Our payroll had risen to around three million a year. The war had cut our potential picture profits in half. The crisis was on. Another one. It was brought on by what might reasonably be called reckless expenditures. Yet, looking at it our way, it is these expenditures that have put us in shape for the storm. Instead of the one feature-length picture every two years which seemed the limit of our capacity two years ago, we are now reorganized and equipped to release nine features in the next two years, each at a fraction of ‘Pinocchio’s’ cost.

The first of these nine features, ‘Fantasia‘, has been released. We have never been so enthusiastic about a picture. Every picture is an adventure, but ‘Fantasia’ has certainly been our most exciting one. We take great music and visualize the stories and pictures which the music suggests to our imagination. It is like seeing a concert. Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra recorded the music, using a new system of sound recording and three-dimensional reproduction called Fantasound. It is our intention to make a new version of ‘Fantasia’ every year. Its pattern is very flexible and fun to work with-not really a concert, not vaudeville or a revue, but a grand mixture of comedy, fantasy, ballet, drama, impressionism, color, sound, and epic fury.

Mickey Mouse in the same boat with Bach, Beethoven, Stravinsky, and Stokowski! Well, where do we go from there? I haven’t the faintest idea. I have never had the faintest idea where this business would drag me from one year to the next. It’s at the controls, not me! But, as I said before, as long as we keep on growing the future will keep opening up. More than any other picture, Fantasia shows how much the medium has grown. No doubt, some unimaginative critics will predict that in ‘Fantasia’ the animated medium and my artists have reached their ultimate. The truth is quite to the contrary. ‘Fantasia’ merely makes our other pictures look immature, and suggests for the first time what the future of this medium may well turn out to be. What I see way off there is too nebulous to describe. But it looks big and glittering. That’s what I like about this business, the certainty that there is always something bigger and more exciting just around the bend; and the uncertainty of everything else.

Over at our entertainment factory we are training hundreds of brilliant youngsters to carry on the job far beyond where we old timers must leave off. They will train other youngsters. There is no knowing how far steady growth will take the medium, if only the technicians continue to give us new and better tools. For the near future, I can practically promise a third-dimensional effect in our moving characters. Fully exploited, Fantasound should prove a startling novelty. The full inspiration and vitality in our animators’ pencil drawings will be brought to the screen in a few years through the elimination of the inking process. Then, too, our medium is peculiarly adaptable to television, and I understand that it is already possible to televise in color. Quite an exciting prospect, I should say! And, since ‘Fantasia’, we have good reason to hope that great composers will write directly for our medium just as they now write for ballet and opera. This is the promise of the next few years. Beyond that is the future which we can not see, today. We, the last of the pioneers and the first of the moderns, will not live to see this future realized. We are happy in the job of building its foundations.

General

Seward Johnson bronzes add a surreal, artistic touch to NYC’s Garment District

Greetings from NYC. Nancy and I drove down from New

Hampshire yesterday because we'll be checking out

Disney Consumer Products' annual Holiday Showcase later today.

Anyway … After checking into our hotel (i.e., The Paul.

Which is located down in NYC's NoMad district), we decided to grab some dinner.

Which is how we wound up at the Melt Shop.

Photo by Jim Hill

Which is this restaurant that only sells grilled cheese sandwiches.

This comfort food was delicious, but kind of on the heavy side.

Photo by Jim Hill

Which is why — given that it was a beautiful summer night

— we'd then try and walk off our meals. We started our stroll down by the Empire

State Building

…

Photo by Jim Hill

… and eventually wound up just below Times

Square (right behind where the Waterford Crystal Times Square New

Year's Eve Ball is kept).

Photo by Jim Hill

But you know what we discovered en route? Right in the heart

of Manhattan's Garment District

along Broadway between 36th and 41st? This incredibly cool series of life-like

and life-sized sculptures that Seward

Johnson has created.

Photo by Jim Hill

And — yes — that is Abraham Lincoln (who seems to have

slipped out of WDW's Hall of Presidents when no one was looking and is now

leading tourists around Times Square). These 18 painted

bronze pieces (which were just installed late this past Sunday night / early

Monday morning) range from the surreal to the all-too-real.

Photo by Jim Hill

Some of these pieces look like typical New Yorkers. Like the

business woman planning out her day …

Photo by Jim Hill

… the postman delivering the mail …

Photo by Jim Hill

… the hot dog vendor working at his cart …

Photo by Jim Hill

Photo by Jim Hill

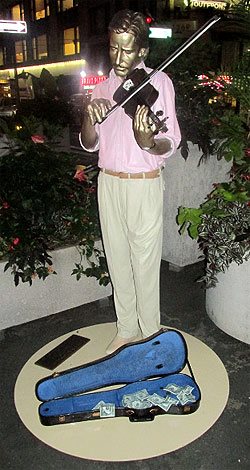

… the street musician playing for tourists …

Photo by Jim Hill

Not to mention the tourists themselves.

Photo by Jim Hill

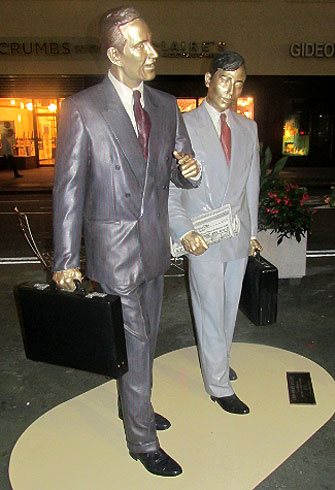

But right alongside the bronze businessmen …

Photo by Jim Hill

… and the tired grandmother hauling her groceries home …

Photo by Jim Hill

… there were also statues representing people who were

from out-of-town …

Photo by Jim Hill

… or — for that matter — out-of-time.

Photo by Jim Hill

These were the Seward Johnson pieces that genuinely beguiled. Famous impressionist paintings brought to life in three dimensions.

Note the out-of-period water bottle that some tourist left

behind. Photo by Jim Hill

Some of them so lifelike that you actually had to pause for

a moment (especially as day gave way to night in the city) and say to yourself

"Is that one of the bronzes? Or just someone pretending to be one of these

bronzes?"

Mind you, for those of you who aren't big fans of the

impressionists …

Photo by Jim Hill

… there's also an array of American icons. Among them

Marilyn Monroe …

Photo by Jim Hill

… and that farmer couple from Grant Wood's "American

Gothic."

Photo by Jim Hill

But for those of you who know your NYC history, it's hard to

beat that piece which recreates Alfred Eisenstaedt's famous photograph of V-J Day in Times Square.

Photo by Jim Hill

By the way, a 25-foot-tall version of this particular Seward

Johnson piece ( which — FYI — is entitled "Embracing Peace") will actually

be placed in Times Square for a few days on or around August 14th to commemorate the 70th

anniversary of Victory Over Japan Day (V-J Day).

Photo by Jim Hill

By the way, if you'd like to check these Seward Johnson bronzes in

person (which — it should be noted — are part of the part of the Garment

District Alliance's new public art offering) — you'd best schedule a trip to

the City sometime over the next three months. For these pieces will only be on

display now through September 15th.

General

Wondering what you should “Boldly Go” see at the movies next year? The 2015 Licensing Expo offers you some clues

Greeting from the 2015 Licensing Expo, which is being held

at the Mandalay Bay

Convention Center in Las

Vegas.

Photo by Jim Hill

I have to admit that I enjoy covering the Licensing Expo.

Mostly becomes it allows bloggers & entertainment writers like myself to

get a peek over the horizon. Scope out some of the major motion pictures &

TV shows that today's vertically integrated entertainment conglomerates

(Remember when these companies used to be called movie studios?) will be

sending our way over the next two years or so.

Photo by Jim Hill

Take — for example — all of "The Secret Life of

Pets" banners that greeted Expo attendees as they made their way to the

show floor today. I actually got to see some footage from this new Illumination

Entertainment production (which will hit theaters on July 8, 2016) the last time I was in Vegas. Which

was for CinemaCon back in April. And the five or so minutes of film that I viewed

suggested that "The Secret Life of Pets" will be a really funny

animated feature.

Photo by Jim Hill

Mind you, Universal Pictures wanted to make sure that Expo

attendees remembered that there was another Illumination Entertainment production

coming-to-a-theater-near-them before "The Secret Life of Pets" (And

that's "Minions," the "Despicable Me" prequel. Which

premieres at the Annecy International Animated Film Festival next week but

won't be screened stateside 'til July 10th of this year). Which is why they had

three minions who were made entirely out of LEGOS loitering out in the lobby.

Photo by Jim Hill

And Warner Bros. — because they wanted "Batman v

Superman: Dawn of Justice" to start trending on Twitter today — brought

the Batmobile to Las Vegas.

Photo by Jim Hill

Not to mention full-sized macquettes of Batman, Superman and

Wonder Woman. Just so conventioneers could then see what these DC superheroes

would actually look like in this eagerly anticipated, March 25, 2016 release.

Photo by Jim Hill

That's the thing that can sometimes be a wee bit frustrating

about the Licensing Expo. It's all about delayed gratification. You'll come

around a corner and see this 100 foot-long ad for "The Peanuts Movie"

and think "Hey, that looks great. I want to see that Blue Sky Studios production

right now." It's only then that you notice the fine print and realize that

"The Peanuts Movie" doesn't actually open in theaters 'til November

6th of this year.

Photo by Jim Hill

And fan of Blue Sky's "Ice Age" film franchise are in for an even

longer wait. Given that the latest installment in that top grossing series

doesn't arrive in theaters 'til July

15, 2016.

Photo by Jim Hill

Of course, if you're one of those people who needs immediate

gratification when it comes to your entertainment, there was stuff like that to

be found at this year's Licensing Expo. Take — for example — how the WWE

booth was actually shaped like a wrestling ring. Which — I'm guessing — meant

that if the executives of World Wrestling Entertainment, Inc. didn't like

the offer that you were making, they were then allowed to toss you out over the

top rope, Royal Rumble-style.

Photo by Jim Hill

I also have to admit that — as a longtime Star Trek fan —

it was cool to see the enormous Starship Enterprise that hung in place over the

CBS booth. Not to mention getting a glimpse of the official Star Trek 50th

Anniversary logo.

Photo by Jim Hill

I was also pleased to see lots of activity in The Jim Henson

Company booth. Which suggests that JHC has actually finally carved out a

post-Muppets identity for itself.

Photo by Jim Hill

Likewise for all of us who were getting a little concerned

about DreamWorks Animation (what with all the layoffs & write-downs &

projects that were put into turnaround or outright cancelled last year), it was

nice to see that booth bustling.

Photo by Jim Hill

Every so often, you'd come across some people who were

promoting a movie that you weren't entirely sure that you actually wanted to

see (EX: "Angry Birds," which Sony Pictures Entertainment / Columbia

Pictures will be releasing to theaters on May 20, 2016). But then you remembered that Clay Kaytis —

who's this hugely talented former Walt Disney Animation Studios animator — is

riding herd on "Angry Birds" with Fergal Reilly. And you'd think

"Well, if Clay's working on 'Angry Birds,' I'm sure this animated feature

will turn out fine."

Photo by Jim Hill

Mind you, there were reminders at this year's Licensing Expo

of great animated features that we're never going to get to see now. I still

can't believe — especially after that brilliant proof-of-concept footage

popped up online last year — that Sony execs decided not to go forward

with production of Genndy Tartakovsky's

"Popeye" movie. But that's the

cruel thing about the entertainment business, folks. It will sometime break

your heart.

Photo by Jim Hill

And make no mistake about this. The Licensing Expo is all

about business. That point was clearly driven home at this year's show when —

as you walked through the doors of the Mandalay

Bay Convention Center

— the first thing that you saw was the Hasbros Booth. Which was this gleaming,

sleek two story-tall affair full of people who were negotiating deals &

signing contracts for all of the would-be summer blockbusters that have already

announced release dates for 2019 & beyond.

Photo by Jim Hill

"But what about The Walt Disney Company?," you

ask. "Weren't they represented on the show floor at this year's Licensing

Expo?" Not really, not. I mean, sure. There were a few companies there hyping

Disney-related products. Take — for example — the Disney Wikkeez people.

Photo by Jim Hill

I'm assuming that some Disney Consumer Products exec is

hoping that Wikkeez will eventually become the new Tsum Tsum. But to be blunt,

these little hard plastic figures don't seem to have the same huggable charm

that those stackable plush do. But I've been wrong before. So let's see what

happens with Disney Wikkeez once they start showing up on the shelves of the

Company's North American retail partners.

Photo by Jim Hill

And speaking of Disney's retail partners … They were

meeting with Mouse House executives behind closed doors one floor down from the

official show floor for this year's Licensing Expo.

Photo by Jim Hill

And the theme for this year's invitation-only Disney shindig? "Timeless

Stories" involving the Disney, Pixar, Marvel & Lucasfilm brands that

would then appeal to "tomorrow's consumer."

Photo by Jim Hill

And just to sort of hammer home the idea that Disney is no

longer the Company which cornered the market when it comes to little girls

(i.e., its Disney Princess and Disney Fairies franchises), check out this

wall-sized Star Wars-related image that DCP put up just outside of one of its

many private meeting rooms. "See?," this carefully crafted photo

screams. "It isn't just little boys who want to wield the Force. Little

girls also want to grow up and be Lords of the Sith."

Photo by Jim Hill

One final, kind-of-ironic note: According to this banner,

Paramount Pictures will be releasing a movie called "Amusement Park"

to theaters sometime in 2017.

Photo by Jim Hill

Well, given all the "Blackfish" -related issues

that have been dogged SeaWorld Parks & Entertainment over the past two years, I'm

just hoping that they'll still be in the amusement park business come 2017.

Your thoughts?

General

It takes more than three circles to craft a Classic version of Mickey Mouse

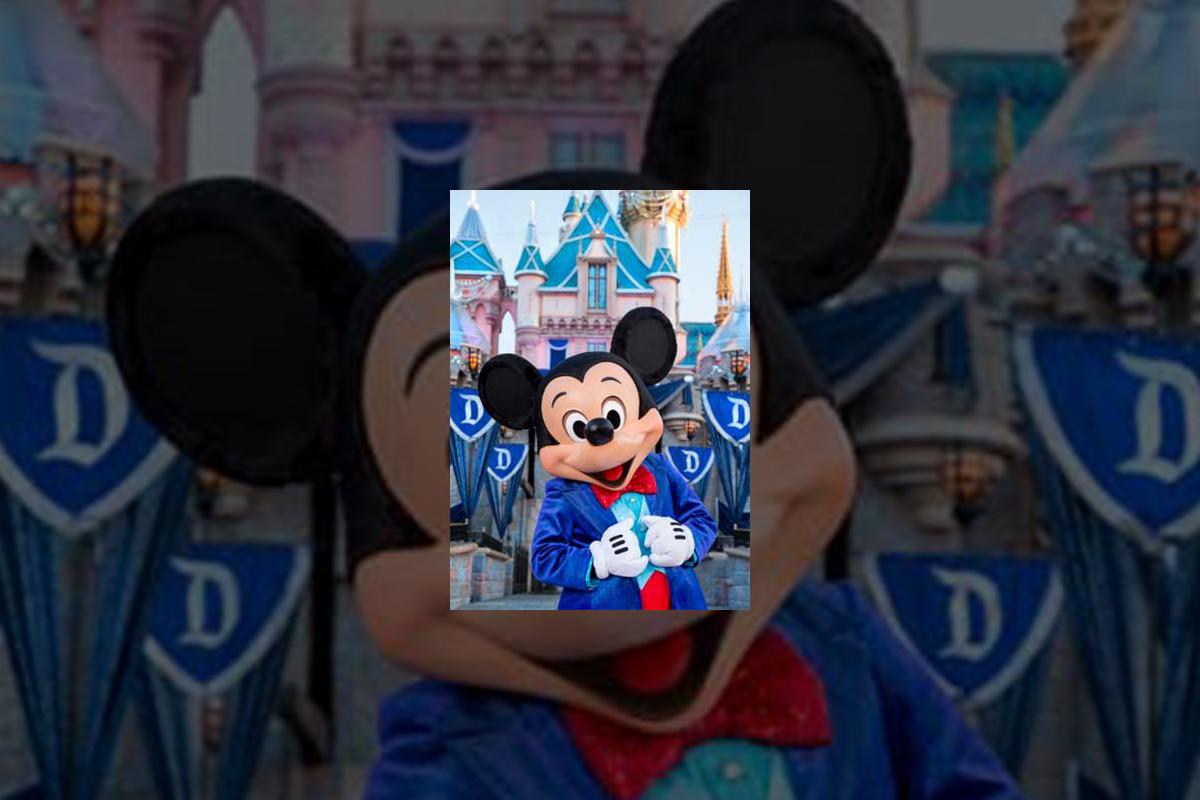

You know what Mickey Mouse looks like, right? Little guy,

big ears?

Truth be told, Disney's corporate symbol has a lot of

different looks. If Mickey's interacting with Guests at Disneyland

Park (especially this summer, when

the Happiest Place on Earth

is celebrating its 60th anniversary), he looks & dresses like this.

Copyright Disney Enterprises,

Inc.

All rights reserved

Or when he's appearing in one of those Emmy Award-winning shorts that Disney

Television Animation has produced (EX: "Bronco Busted," which debuts

on the Disney Channel tonight at 8 p.m. ET / PT), Mickey is drawn in a such a

way that he looks hip, cool, edgy & retro all at the same time.

Copyright Disney Enterprises, Inc. All rights

reserved

Looking ahead to 2017 now, when Disney Junior rolls out "Mickey and the

Roadster Racers," this brand-new animated series will feature a sportier version

of Disney's corporate symbol. One that Mouse House managers hope will persuade

preschool boys to more fully embrace this now 86 year-old character.

Copyright Disney Enterprises,

Inc. All rights reserved

That's what most people don't realize about the Mouse. The

Walt Disney Company deliberately tailors Mickey's look, even his style of

movement, depending on what sort of project / production he's appearing in.

Take — for example — Disney

California Adventure

Park's "World of Color:

Celebrate!" Because Disney's main mouse would be co-hosting this new

nighttime lagoon show with ace emcee Neil Patrick Harris, Eric Goldberg really had

to step up Mickey's game. Which is why this master Disney animator created

several minutes of all-new Mouse animation which then showed that Mickey was

just as skilled a showman as Neil was.

Copyright Disney Enterprises,

Inc.

All rights reserved

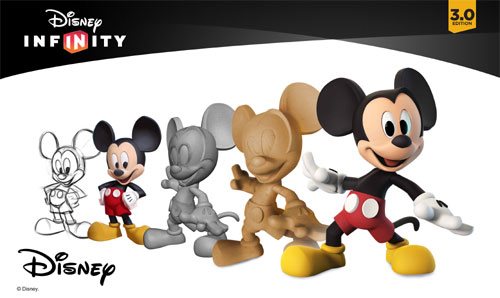

Better yet, let's take a look at what the folks at Avalanche Studios just went

through as they attempted to create a Classic version of Mickey & Minnie.

One that would then allow this popular pair to become part of Disney Infinity

3.0.

"I won't lie to you. We were under a lot of pressure to

get the look of this particular version of Mickey — he's called Red Pants

Mickey around here — just right," said Jeff Bunker, the VP of Art

Development at Avalanche Studios, during a recent phone interview. "When

we brought Sorcerer Mickey into Disney Infinity 1.0 back in January of 2014,

that one was relatively easy because … Well, everyone knows what Mickey Mouse

looked like when he appeared in 'Fantasia.' "

Copyright Disney Enterprises,

Inc. All rights reserved

"But this time around, we were being asked to design

THE Mickey & Minnie," Bunker continued. "And given that these Classic

Disney characters have been around in various different forms for the better

part of the last century … Well, which look was the right look?"

Which is why Jeff and his team at Avalanche Studios began watching hours &

hours of Mickey Mouse shorts. As they tried to get a handle on which look would

work best for these characters in Disney Infinity 3.0.

Copyright Disney

Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved

"And we went all the way back to the very start of Mickey's career. We began

with 'Steamboat Willie' and then watched all of those black & white Mickey shorts

that Walt made back in the late 1920s & early 1930s. From there, we

transitioned to his Technicolor shorts. Which is when Mickey went from being

this pie-eyed, really feisty character to more of a well-behaved leading

man," Bunker recalled. "We then finished out our Mouse marathon by

watching all of those new Mickey shorts that Paul Rudish & his team have

been creating for Disney Television Animation. Those cartoons really recapture

a lot of the spirit and wild slapstick fun that Mickey's early, black &

white shorts had."

But given that the specific assignment that Avalanche Studios had been handed

was to create the most appealing looking, likeable version of Mickey Mouse

possible … In the end, Jeff and his team wound up borrowing bits & pieces

from a lot of different versions of the world's most famous mouse. So that

Classic Mickey would then look & move in a way that best fit the sort of

gameplay which people would soon be able to experience with Disney Infinity

3.0.

Copyright Disney Enterprises,

Inc. All rights reserved

"That — in a lot of ways — was actually the toughest

part of the Classic Mickey design project. You have to remember that one of the

key creative conceits of Disney Infinity

is that all the characters which appear in this game are toys," Bunker

stated. "Okay. So they're beautifully detailed, highly stylized toy

versions of beloved Disney, Pixar, Marvel & Lucasfilm characters. But

they're still supposed to be toys. So our Classic versions of Mickey &

Minnie have the same sort of thickness & sturdiness to them that toys have.

So that they'll then be able to fit right in with all of the rest of the

characters that Avalanche Studios had previously designed for Disney Infinity."

And then there was the matter of coming up with just the

right pose for Classic Mickey & Minnie. Which — to hear Jeff tell the

story — involved input from a lot of Disney upper management.

Copyright Disney Enterprises,

Inc. All rights reserved

"Everyone within the Company seemed to have an opinion

about how Mickey & Minnie should be posed. More to the point, if you Google

Mickey, you then discover that there are literally thousands of poses out there

for these two. Though — truth be told — a lot of those kind of play off the

way Mickey poses when he's being Disney's corporate symbol," Bunker said.

"But what I was most concerned about was that Mickey's pose had to work

with Minnie's pose. Because we were bringing the Classic versions of these

characters up into Disney Infinity 3.0 at the exact same time. And we wanted to

make sure — especially for those fans who like to put their Disney Infinity

figures on display — that Mickey's pose would then complement Minnie.

Which is why Jeff & the crew at Avalanche Studios

decided — when it came to Classic Mickey & Minnie's pose — that they

should go all the way back to the beginning. Which is why these two Disney icons

are sculpted in such a way that it almost seems as though you're witnessing the

very first time Mickey set eyes on Minnie.

Copyright Disney Enterprises,

Inc. All rights reserved

"And what was really great about that was — as soon as

we began showing people within the Company this pose — everyone at Disney

quickly got on board with the idea. I mean, the Classic Mickey that we sculpted

for Disney Infinity 3.0 is clearly a very playful, spunky character. But at the

same time, he's obviously got eyes for Minnie," Bunker concluded. "So

in the end, we were able to come up with Classic versions of these characters

that will work well within the creative confines of Disney Infinity 3.0 but at

the same time please those Disney fans who just collect these figures because

they like the way the Disney Infinity characters look."

So now that this particular design project is over, does

Jeff regret that Mouse House upper management was so hands-on when it came to

making sure that the Classic versions of Mickey & Minnie were specifically

tailored to fit the look & style of gameplay found in Disney Infinity 3.0?

Copyright Lucasfilm / Disney

Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved

"To be blunt, we go through this every time we add a new character to the

game. The folks at Lucasfilm were just as hands-on when we were designing the

versions of Darth Vader and Yoda that will also soon be appearing in Disney

Infinity 3.0," Bunker laughed. "So in the end, if the character's

creators AND the fans are happy, then I'm happy."

This article was originally posted on the Huffington Post's Entertainment page on Tuesday, June 9, 2015

-

Film & Movies10 months ago

Film & Movies10 months agoBefore He Was 626: The Surprisingly Dark Origins of Disney’s Stitch

-

History8 months ago

History8 months agoCalifornia Misadventure

-

Film & Movies9 months ago

Film & Movies9 months agoThe Best Disney Animation Film Never Made – “Chanticleer”

-

Television & Shows10 months ago

Television & Shows10 months agoThe Untold Story of Super Soap Weekend at Disney-MGM Studios: How Daytime TV Took Over the Parks

-

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment8 months ago

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment8 months agoThe ExtraTERRORestrial Files

-

History9 months ago

History9 months agoWhy Disney’s Animal Kingdom’s Beastly Kingdom Was Never Built

-

Podcast11 months ago

Podcast11 months agoEpic Universal Podcast – Aztec Dancers, Mariachis, Tequila, and Ceremonial Sacrifices?! (Ep. 45)