Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment

Ruminations

If there are two topics you can depend on Roger to give you more information about, they are Disney and railroading. This week, he puts them together in a look at just some of the Disney movies that have featured trains.

Okay a couple of things before get started on this scholarly (read long) effort today. Don’t be misled by all of the railroad aspects of this story. There are a lot of Disney tidbits in it as well.

A couple of things of note from the San Francisco Chronicle for August 20, 2003.

It looks like Trader Vic’s will be back in San Francisco sometime next year. Today’s Food Section mentions that it will be moving into the location at 555 Golden Gate Avenue that used to be Stars. Earthquake retrofitting will keep them busy for a while. More details as I get them to pass along. One item has the creation of a place called Old Havana with a Cuban influence as part of the project — complete with lots of rum drinks!

The front page carried this story about a woman who died after being attacked by a great white shark (a.k.a. Bruce from “Jaws”) while swimming 75 yards off of Avila Beach on the California Coast. Now any death is tragic, but this one seriously qualifies for the Darwin Awards, in my opinion. This woman had been swimming along the coast for a number of years, so she should have known about sharks. Specifically that these sharks favor seals as the food of choice. So? What does she do? She’s dressed in a black full body wet suit, and is out swimming with… THE SEALS!!! And the shark, out for a snack, swims up to the pack, and goes in for the kill, getting this woman, instead of a seal. And to add to the irony, there was a group of lifeguards on shore not far away doing a series of competitions nearby.

So that’s from the news…

Now to the story for today.

Our textbook — Walt Disney’s Railroad Story by Michael Broggie. Regrettably, after two printings (a total of 17,000 copies), this book is currently out of print. Checking Amazon or eBay, you might find a copy for sale, but at a premium price. Giving Mr. Broggie credit, this volume is a fine work. Now the book does tell the tale of Walt and his love of railroads. But only briefly is addressed is how that crossed over into movies. It doesn’t go quite far enough. A small sidebar covers “The Great Locomotive Chase” with Fess Parker, but doesn’t really tell the whole story.

That’s like offering you a fine meal, but only serving one course. Rather than have you go away hungry, allow me to serve up the rest.

In particular, we’ll be looking at three movies. The first two were made when Walt was still alive, and the last involved one the most well know steam locomotives in the country.

Astute readers of the book may recall that Ward Kimball’s “Grizzly Flats Railroad” was a favorite of Walt’s as well. But it lacked something every railroad needs — a station building. Mr. Broggie well relates the tale of how Ward convinced Walt to give him the set pieces that made up the depot structure from the film “So Dear To My Heart”. And it tells the tale of how Ward and company assembled the pieces as best they could, matching paint. Now remember this was only a three sided set, not a real station building. Using a crane, the crew set the roof on the structure, only to have it collapse under it’s own weight. There simply wasn’t sufficient framing to hold it up.

The final result admired as the Grizzly Flats station ended up being an almost new structure using very little of the set pieces. Most notable were the doors and windows. Ward recalled later that he could have built the building from scratch for less than in finally cost him.

The book also recounts how the drawings for the station (done by Ward) ended up being used as the basis for Disneyland’s Frontierland station structure.

The “E.P. Ripley”, Santa Fe & Disneyland #2 arrives on the platform

at the Frontierland Station with the Holiday One trainset.

Photo by Roger Colton.

Now what it doesn’t tell is the story of the locomotive used in the film. And considering the subject, that’s a shame. But not to worry, cause that’s a gap I’m going to fill in today.

This part of today’s tale goes way back, and into my neck of the woods, to Nevada. One of my earlier efforts told the tale of Billy Ralston and his Bank of California. In an effort to extend their control over Virginia City and the Comstock, they built a railroad. Originally conceived as the means of transporting ore from the mines to their mills for processing, it became the connection to both the East and West coasts by connecting with the Central Pacific nearby at Reno.

A new railroad needed new equipment to do the job, and the Virginia & Truckee ordered locomotives from several sources. One company was the Baldwin Locomotive Works in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Having experienced success with previous orders, the V&T looked to Baldwin again, and on March 22, 1875, their latest product arrived in Reno. “Inyo”, the name applied, is Indian term meaning “dwelling place of a great spirit.” It is also affixed to a lengthy mountain range and a large county in eastern California. At a cost of $9,065, she was the latest word in technology. Given the number 22 on the railroad’s roster, she served a long career. Here’s a link to more details.

The glory days of the V&T lasted as long as the ore was profitable on the Comstock. When boom turned to borrasca, many of the railroad’s locomotives were stored out of service in the great stone enginehouse in Carson City. “Inyo” was one of those, considered retired after 1926, but seeing occasional service as needed.

In what could easily be called kismet, the V&T was discovered by the folks in Hollywood. John Ford’s 1924 silent film, “The Iron Horse” made extensive use of the V&T. The use locomotives and cars from the era of the construction of the transcontinental railroad undoubtedly contributed to the first major success of Ford’s career. Yet as realistic as the location and equipment were, it wasn’t practical to send a company out there for every picture requiring a train.

So, the studios did the next best thing. They bought the train and made use of it closer to home, if not on the backlot. The “Inyo” was one of the first to go, to Paramount, appearing first in 1937’s “High, Wide and Handsome“. In 1939, she appeared in Cecil B. Demille’s “Union Pacific” (covering the same subject as Ford’s “Iron Horse, although not as well, in my opinion).

The locomotive was used in Disney’s “Great Locomotive Chase” in 1956. Filmed on location in Georgia, “Inyo” appeared in the guise of the “Texas”, while the Baltimore & Ohio’s “William Mason” (from the B&O Museum in Baltimore) did the duty as the “General”. The Museum also contributed the “Lafayette” appearing as the yard locomotive “Yonah”. This link offers more info on both and others in the B&O Museum collection. (The Museum suffered tragic damage this last winter when part of the roof of the historic roundhouse where locomotives and cars were on display collapsed under the weight of record snowfall. Luckily, both of these locomotives were not in the building at that time.)

Now for the ironic element of the story. For television’s “Wild Wild West”, the “Inyo” was one of several locomotives to appear in various views hauling the private train of Secret Service agents James West and Artemus Gordon. This link offers a glimpse into more history of that production. (The pilot episode for the series featured the Sierra Railroad at Jamestown, California (which you might remember from another effort) and their locomotive #3, star of many other tv shows and movies — most recently as the locomotive in “Back to the Future III.”) In the recent movie version of the “Wild Wild West,” it was the “William Mason” that took the role as the locomotive on the train or the “Wanderer” as it has become known.

Among many other movie and television roles, “Inyo” appeared in “So Dear To My Heart” along with the Ward Kimball station at Fulton’s Corners. And just as the station survives (somewhat) at Ward’s Grizzly Flats Railroad, the “Inyo” survives at the Nevada State Railroad Museum in Carson City.

Much of the V&T’s equipment that survived into the later years found it’s way to Hollywood. The “Inyo” and sister locomotive “Dayton” found their way to Utah’s Promontory Point (The Gold Spike National Historic Site) where they stood in for the original locomotives for the centennial of the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1969.

The two locomotives from 1869, Union Pacific #119 and Central Pacific “Jupiter” were both scrapped after years of productive service on their respective railroads. In 1980, the National Park Service had replicas created by Chadwell O’Connor Engineering of Costa Mesa with assistance from Ward Kimball.

Chad O’Connor also has a Disney connection. During an afternoon of filming trains on the platform at the Southern Pacific’s Glendale station, he was approached by someone who was interested in his unique camera setup. That setup was the early version of the fluid head camera mount allowing smooth camera movements. The person he was approached by was Walt Disney, and O’Connor was hired to provide his fluid head mount (for which he later won a special Oscar for technical achievement) for Disney’s True to Life series of films.

“Dayton” was another veteran of films and was purchased by the State of Nevada along with the “Inyo” and other equipment from Paramount in 1974. Both came back to Carson City and are restored to museum standards. “Inyo” has been to many events since including the 1986 Vancouver World’s Fair. She is under steam on a regular basis, bringing her history back to life for Museum guests.

At the Nevada State Railroad Museum in Carson City, “Inyo”

under steam with “Dayton” on display behind.

Photo by Roger Colton.

The “Dayton” has a further Disney connection. She was one of ten of her class built by the Central Pacific in their Sacramento shops in1873. The V&T purchased two identical locomotives from this group. One other locomotive in this group was numbered 173. That was the same locomotive that Walt Disney based his “Carolwood & Pacific” “Lilly Belle” upon using original Central Pacific construction drawings.

Moving up the timeline, how about Disney’s “Pollyanna?” You might recall that I mentioned that the location where the movie’s opening scenes were filmed. That was the Southern Pacific’s branch line to Calistoga, and today you can enjoy a trip on the Napa Wine Train to the same train station in St. Helena. The train seen in those opening and closing moments of the film? Yes, it’s still around today. The locomotive, Watertown & Eastern #94? That’s the next chapter…

In 1909, the Western Pacific Railroad was building its line from a connection with the Denver & Rio Grande and the Missouri Pacific to complete the rail empire of industrialist Jay Gould. When finished, the WP promised to open ports in the West, breaking the monopoly of the Harriman railroads — the Southern Pacific and the Union Pacific. This would have the effect of opening the Pacific rim to rest of the nation as cargos could flow both in and out of the ports of San Francisco and Oakland at favorable rates.

The WP ordered new locomotives based on tried and true designs then in use on the parent railroads. Blessed by design with minimal grades, standards were adopted to keep passengers and freight moving. The new company turned to the American Locomotive Company and ordered a series of locomotives that would see service for the next forty years.

To celebrate the opening of the route, the railroad operated the “Press Representative Special” from Salt Lake to Oakland. Along with the members of the Fourth Estate were a variety of local dignitaries. Stops were made at important points along the way to offer opportunities to explore the wonders of this new route.

Of the locomotives that pulled that train, one survived on the roster of the railroad until 1964. Number 94 was one of 21 locomotives in its class. Builders #46446 was designed to pull trains of eight to ten cars at speeds up to seventy miles per hour over the railroad. It pulled the special train through the scenic Feather River canyon between Portola and Oroville in the summer of 1910. After that it was one of the workhorses of the fleet on trains such as the Scenic Limited and the Feather River Express.

WP employee Gilbert Kneiss should be given the credit for seeing to it that the railroad preserved this locomotive. When due to be retired and scrapped in 1948, he convinced railroad officials that it could be renovated and used to celebrate the 40th anniversary or Ruby Jubilee of the line’s opening. While her sisters were scrapped (as diesel electric locomotives came into service, saving costs in labor and fuel), she was to be saved for the future.

The railroad used the 94 for those anniversary celebrations and then made her available for excursions over the next few years. In 1953, she was restored to her original appearance with gold leaf for striping and lettering. The next time you watch “Pollyanna,” note the “Watertown & Eastern” lettering applied by the Disney artists for the film. After filming was completed, they reapplied the Western Pacific lettering over it. (That was the source of a great joke years later when we repainted the tender after removing the Disney lettering. On several occasions we got some kid to ask our master mechanic what Watertown & Eastern stood for. It was usually good for a quick rise as he was one of the folks who operated the sand blaster removing it!)

The last outing for the 94 again as to celebrate an anniversary, this time the 50th. She made a trip from Oakland to Niles where she was placed in the front of the California Zephyr for the final miles into Oakland. Then she sat in storage in a roundhouse with other historic equipment awaiting a museum home. Finally in 1964, she was donated to the San Francisco Maritime Museum Association for a combined rail and maritime museum project proposed for San Francisco’s Fisherman’s Wharf Area. While waiting for that to occur, she was moved to join other equipment belonging to the Pacific Coast Chapter of the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society in shed near the toll plaza of the San Francisco – Oakland Bay Bridge.

When the museum project fell through, she sat forgotten by most of the rail fans in the area. In the mid Seventies, the shed where she was stored was slated to be removed to allow for expansion of facilities at the Oakland Army Base/Port of Oakland. Two very dedicated volunteers from the California Railway Museum at Rio Vista Junction were instrumental in convincing the Board of the Maritime Museum Association that they could restore the locomotive and several others to operation. They had already done so with one locomotive (that their museum did not fully own), and were now looking for another project. Their timing was just right.

Ross Cummings and Gerry Hanford were those two people. Ross was a specialty machinist restoring vintage racecars. Gerry was a member of a team that had restored as well as even built locomotives. (The Redwood Valley Railroad recreates railroading as it might have been on the California North Coast at the turn of the Twentieth Century, albeit in a smaller, but very accurate scale.) They lead an effort that got folks like me involved in every filthy job needed to get the 94 ready to move on her own wheels in the spring of 1979.

The WP provided a special train with a locomotive and a caboose that towed the 94 over the same rails she had seen in service for over fifty years. Arriving at Rio Vista Junction, further repairs were completed that allowed the operation under steam for the first time in almost twenty years. During those first days, we were all very proud as the 94 was quite the lady back in service, even if only on a short leash.

At speed on the Museum mainline in 1980.

Photo by Roger Colton.

Now locomotives are just like other machines and they do wear out. The stresses of operation take their toll. Such was the case with the 94. She last operated in the summer of 1989 on a special train for a potential donor. Since then she has been stored out of view of Museum visitors inside a barn at Rio Vista Junction with a very bleak future.

Her last complete overhaul was in 1949 by the WP. While we were able to do some repairs at the Museum, it was simply time for a more involved restoration. The boiler shell needed to be checked for soundness. The boiler tubes and flues were at the end of their lifetimes. Replacement was the only option. And we were noting other signs of age as well that could no longer be ignored. A plan was formulated and a budget adopted.

Things changed at the Museum. First came a name change (to the Western Railway Museum) to avoid confusion with the State railroad museum in Sacramento. Later, a clique of members who have been in power for more than thirty years decided not to pursue further steam operations. Finally they ended all steam restoration projects and passenger train service, with the goal of seeing folks who supported both (such as myself) leaving once their projects were no longer viable or funded. A very cold, callous and calculated series of actions all cleverly manipulated to get the intended results. (No links to the Western Railway Museum nor do I encourage anyone to support any of their activities in any way, shape or form.)

It’s not impossible that the 94 will again steam, just unlikely for a while.

The last locomotive in this story was one of the major players in the Touchstone production of “Tough Guys” with Kirk Douglas and Burt Lancaster. Filmed on location in the Taylor Yard complex of the Southern Pacific in Los Angeles and on the Kaiser Steel railroad near Fontana, this train was as much a part of history as the “Gold Coast Flyer” it portrayed.

The Southern Pacific Railroad offered passenger service along the California coast between San Francisco and Los Angeles. In the days before Highway 101 or Interstate 5, and before the advent of air travel, the Espee was the only way for many travelers to get to their destinations. Following the route established by the Spanish with their Missions, the railroad travels for 113 miles along the shore of the Pacific Ocean. As the Depression was coming to an end, the president of the railroad looked for ways to increase passenger traffic. Equipping the premier train in 1939 with new cars and locomotives in an attractive paint scheme of red, orange and black, the “Coast Daylight” was an overwhelming success. So much so that extra sections of the train were sold out as well! (While I don’t know for certain, it is very possible that Walt might have ridden on the “Daylight” or one of the other trains of the Coast route at some point, perhaps pulled by one of those new locomotives.)

My mother has many fond memories of riding the streetcar from her home on San Francisco’s Twenty-Ninth Avenue to the downtown station of the Southern Pacific at Third and Townsend Streets (today the location of Pacific Bell Park — home of the San Francisco Giants!) to board the “Daylight” for the ride to San Luis Obispo to spend time with her maternal grandparents. It was exciting for everyone, not just young girl! A particular highlight was a meal in the dining car, served on the railroads Prairie Mountain Wildflower china with silver and linen as well.

The locomotives ordered for the train were the latest in superpower technology. Produced by the Lima Locomotive Works in Lima, Ohio, they were streamlined and fast. Called the Golden State or GS classes, there were over 60 of these destined for service across the Espee system. From the premiere passenger train, they went to secondary trains, then to commute service between San Francisco and San Jose, and finally into freight service. (My great grandfather’s last trip as an engineer was made aboard one pulling a mail train from Carlin to Sparks, Nevada in 1950.) The last one was replaced by diesel locomotives in 1958. Two were saved for museums. One went to St Louis, Missouri and the other to Portland, Oregon. It looked like a quiet retirement for both.

In the early Seventies, a group was looking for ways to celebrate the upcoming Bicentennial of the United States. One concept had a train traveling the country to exhibit rare artifacts for the nation’s past, including the Declaration of Independence. Rather than simply use diesel locomotives from the current railroads, they decided to look around the country for a steam locomotive with enough historic significance to be part of the exhibits it’s self. A team traveled to country looking at many potential candidates. In the end, they chose two – one from the east and one from the west. The western choice? One of those two remaining Daylight steam locomotives. Number 4449, in Portland, Oregon, was restored to operating condition.

Painted red, white and blue, she traveled east from to join the train in 1975 and toured a good deal of the country ending up in Florida in 1977. To get home to Portland, she carried the “Amtrak Transcontinental Steam Excursion”, making day trips between cities along the way. In 1981, she was repainted into her distinctive “Daylight” colors and traveled to Sacramento for the opening celebrations for the California State Railroad Museum. (As an amusing side note, the Western Pacific 94 was specifically not invited to participate, but was in operation under steam less than twenty five miles away, during the festivities.)

In 1984, she was again under steam with a complete train. The “World’s Fair Daylight” traveled from Portland to New Orleans along the Espee route, again carrying passengers on day trips.

For “Tough Guys”, she traveled down in early 1986 to Los Angeles. Her engineer, Doyle McCormack, even has a speaking role as the train’s engineer. “No one robs trains anymore.” The Disney studio folks built two replicas of the 4449 for the movie. One was a full size replica of the locomotive cab’s interior that rode on a flatcar. It was easier to film than in the real cab. The other replica was a full-size mock-up for the scenes at the end of the film where the train crashes through the fence at the Mexican border. (Not to worry, they used a miniature for the very convincing action scenes.) The replica appeared after the incident, complete with the following dialogue: “Gee, we wrecked their train.” “Well, they weren’t going to use it any more anyway.” As much of a train enthusiast as Walt was, I know he would have enjoyed it.

The “Gold Coast Flyer” in the Espee’s Taylor Yard in 1986.

Photo collection of Roger Colton.

I chased the train both down to San Luis Obispo with Jeff Ferris and another railfan (who will remain anonymous, as he’s still working on a railroad) and then back from Los Angeles several months later. That was quick a shock to my wife to be as she later learned that I had been out doing this the week before we were getting married. (Seventeen years later she still hasn’t forgiven me.)

The 4449 has appeared on various excursions since that time. In 2002, she was repainted into her Freedom Train colors and made several trips out of Portland. She’s on display right now at the upcoming Oregon State Fair until September 1.

So there you have it. More tales about railroads and Disney films.

Be back next week for another thrilling chapter in Roger’s “Things You Always Wanted To Do…” series as we head out onto the open range! “Saddle up! We’re burning daylight!”

Thanks again to everyone for supporting these efforts through Roger’s Amazon Honor System Paybox. It keeps him going during these long hours at the keyboards.

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment

Disney and Macy’s 90-Year Thanksgiving Day Parade Partnership: From Mickey’s First Balloon to Minnie’s Big Debut

Now, folks, if you’re like me, Thanksgiving just wouldn’t be the same without a coffee, a cozy seat, and Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade on the TV. And if you’re really like me, you’re watching for one thing: Disney balloons floating down 34th Street. Ever wondered how Mickey, Donald, and soon Minnie Mouse found their way into this beloved New York tradition? Well, grab your popcorn because we’re diving into nearly 90 years of Disney’s partnership with Macy’s.

The Very First Parade and the Early Days of Balloons

The Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade goes way back to 1924, but if you can believe it, balloons weren’t part of the festivities until 1927. That first lineup included Felix the Cat, a dragon, and a toy soldier, all towering above the crowds. Back then, Macy’s had a pretty wild idea to end the parade: they would let the balloons drift off into the sky, free as birds. But this wasn’t just Macy’s feeling generous. Each balloon had a message attached, offering a $100 reward (about $1,800 in today’s dollars) for anyone who returned it to the flagship store on 34th Street.

And here’s where it gets interesting. This tradition carried on for a few years, right up until 1932, when Felix the Cat almost took down a plane flying over New York City! Imagine that—you’re flying into LaGuardia, and suddenly, there’s a 60-foot balloon drifting toward your wing. Needless to say, that was the end of Macy’s “fly away” stunt, and from then on, the balloons have stayed firmly grounded after the parade ends.

1934: Mickey Mouse Floats In, and Disney Joins the Parade

It was 1934 when Mickey Mouse finally made his grand debut in the Macy’s parade. Rumor has it Walt Disney himself collaborated with Macy’s on the design, and by today’s standards, that first Mickey balloon was a bit of a rough cut. This early Mickey had a hotdog-shaped body, and those oversized ears gave him a slightly lopsided look. But no one seemed to mind. Mickey was there, larger than life, floating down the streets of New York, and the crowd loved him.

Mickey wasn’t alone that year. He was joined by Pluto, Horace Horsecollar, and even the Big Bad Wolf and Practical Pig from The Three Little Pigs, making it a full Disney lineup for the first time. Back then, Disney wasn’t yet the entertainment powerhouse we know today, so for Walt, getting these characters in the parade meant making a deal. Macy’s required its star logo to be featured on each Disney balloon—a small concession that set the stage for Disney’s long-standing presence in the parade.

Duck Joins and Towers Over Mickey

A year later, in 1935, Macy’s introduced Donald Duck to the lineup, and here’s where things got interesting. Mickey may have been the first Disney character to float through the parade, but Donald made a huge splash—literally. His balloon was an enormous 60 feet tall and 65 feet long, towering over Mickey’s 40-foot frame. Donald quickly became a fan favorite, appearing in the lineup for several years before being retired.

Fast-forward a few decades, and Donald was back for a special appearance in 1984 to celebrate his 50th birthday. Macy’s dug the balloon out of storage, re-inflated it, and sent Donald down 34th Street once again, bringing a bit of nostalgia to the holiday crowd.

A Somber Parade in 2001

Now, one of my most memorable trips to the parade was in 2001, just weeks after the 9/11 attacks. Nancy and I, along with our friends, headed down to New York, and the mood was something I’ll never forget. We watched the start of the parade from Central Park West, but before that, we went to the Museum of Natural History the night before to see the balloons being inflated. They were covered in massive cargo nets, with sandbags holding them down. It’s surreal to see these enormous balloons anchored down before they’re set free.

That year, security was intense, with police lining the streets, and then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani rode on the Big Apple float to roaring applause. People cheered his name, waving and shouting as he passed. It felt like the entire city had turned out to show their resilience. Even amidst all the heightened security and tension, seeing those balloons—brought a bit of joy back to the city.

Balloon Prep: From New Jersey’s MetLife Stadium to California’s D23 Expo

Each year before the parade, Macy’s holds a rehearsal event known as Balloon Fest at MetLife Stadium in New Jersey. This is where handlers get their first crack at guiding the balloons, practicing with their parade masters, and learning the ropes—literally. It’s an entire production unto itself, with dozens of people rehearsing to make sure these enormous inflatables glide smoothly down the streets of New York on parade day.

In 2015, Macy’s took the balloon show on the road, bringing their Buzz Lightyear balloon out to California for the D23 Expo. I was lucky enough to be there, and watching Buzz get inflated piece by piece in the Anaheim Convention Center parking lot was something to behold. Each section was filled with helium in stages, and when they got around to Buzz’s lower half, well, there were more than a few gas-related jokes from the crowd.

These balloons seem to have a personality all their own, and seeing one like Buzz come to life up close—even outside of New York—had all the excitement and anticipation of the real deal.

Mickey’s Comeback as a Bandleader and Sailor Mickey

After a long hiatus, Mickey Mouse made his return to the Macy’s parade in 2000, this time sporting a new bandleader outfit. Nine years later, in 2009, Sailor Mickey joined the lineup, promoting Disney Cruise Line with a nautical twist. Over the past two decades, Disney has continued to enchant parade-goers with characters like Buzz Lightyear in 2008 and Olaf from Frozen in 2017. These balloons keep Disney’s iconic characters front and center, drawing in both longtime fans and new viewers.

But ever wonder what happens to the balloons after they reach the end of 34th Street? They don’t just disappear. Each balloon is carefully deflated, rolled up like a massive piece of laundry, and packed into storage bins. From there, they’re carted back through the Lincoln Tunnel to Macy’s Parade Studio in New Jersey, where they await their next flight.

Macy’s Disney Celebration at Hollywood Studios

In 1992, Macy’s took the spirit of the parade down to Disney-MGM Studios in Orlando. After that year’s parade, several balloons—including Santa Goofy, Kermit the Frog, and Betty Boop—were transported to Hollywood Studios, re-inflated, and anchored along New York Street as part of a holiday display. Visitors could walk through this “Macy’s New York Christmas” setup and see the balloons up close, right in the middle of the park. While this display only ran for one season, it paved the way for the Osborne Family Spectacle of Dancing Lights, which became a holiday staple at the park for years to come.

Minnie Mouse’s Long-Awaited Debut in 2024

This year, Minnie Mouse will finally join the parade, making her long-overdue debut. Macy’s is rolling out the red carpet for Minnie’s arrival with special pop-up shops across the country, where fans can find exclusive Minnie ears, blown-glass ornaments, T-shirts, and more to celebrate her first appearance in the Thanksgiving Day Parade.

For those lucky enough to catch the parade this year, you’ll see Minnie take her first float down 34th Street, decked out in her iconic red bow and polka-dot dress. Macy’s and Disney are also unveiling a new Disney Cruise Line float honoring all eight ships, including the latest, the Disney Treasure.

As always, I’ll be watching from my favorite chair, coffee in hand, as Minnie makes her grand entrance. The 98th annual Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade airs live on NBC, and it’s a tradition you won’t want to miss—whether you’re on 34th Street or tuning in from home.

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment

Disney’s Forgotten Halloween Event: The Original Little Monsters on Main Street

When most Disney fans think of Halloween in the parks, they immediately picture Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party at Walt Disney World or the Oogie Boogie Bash at Disneyland Resort. But before those events took over as the must-attend spooky celebrations, there was a little-known event at Disneyland called Little Monsters on Main Street. And its origins? Well, they go all the way back to the 1980s, during a time when America was gripped by fear—the Satanic Panic.

You see, back in the mid-1980s, parents were terrified that Halloween had become dangerous. Urban legends about drug-laced candy or razor blades hidden in apples were widespread, and many parents felt they couldn’t let their kids out of sight for even a moment. Halloween, which was once a carefree evening of trick-or-treating in the neighborhood, had suddenly become a night filled with anxiety.

This is where Disneyland’s Little Monsters on Main Street came in.

The Origins of Little Monsters on Main Street

Back in 1989, the Disneyland Community Action Team—later known as the VoluntEARS—decided to create a safe, nostalgic Halloween experience for Cast Members and their families. Many schools in the Anaheim area were struggling to provide basic school supplies to students, and the VoluntEARS saw an opportunity to combine a safe Halloween with a charitable cause. Thus, Little Monsters on Main Street was born.

This event was not open to the general public. Only Disneyland Cast Members could purchase tickets, which were initially priced at just $5 each. Cast Members could bring their kids—but only as many as were listed as dependents with HR. And even then, the park put a cap on attendance: the first event was limited to just 1,000 children.

A Unique Halloween Experience

Little Monsters on Main Street wasn’t just another Halloween party. It was designed to give kids a safe, fun environment to enjoy trick-or-treating, much like the good old days. On Halloween night in 1989, kids in costume wandered through Disneyland with their pillowcases, visiting 20 different trick-or-treat stations. They also had the chance to ride a few of their favorite Fantasyland attractions, all after the park had closed to the general public.

The event was run entirely by the VoluntEARS—about 200 of them—who built and set up all the trick-or-treat stations themselves. They arrived at Disneyland before the park closed and, as soon as the last guest exited, they began setting up stations across Main Street, Adventureland, Frontierland, Fantasyland, and Tomorrowland. The event ran from 7:30 to 9:30 p.m., and by the time the last pillowcase-wielding kid left, the VoluntEARS cleaned everything up, making sure the park was ready for the next day’s operations.

It wasn’t just candy and rides, though. The event featured unique entertainment, like a Masquerade Parade down Main Street, U.S.A., where kids could show off their costumes. And get this—Disneyland even rigged up a Cast Member dressed as a witch to fly from the top of the Matterhorn to Frontierland on the same wire that Tinker Bell uses during the fireworks. Talk about a magical Halloween experience!

The Haunted Mansion “Tip-Toe” Tour

Perhaps one of the most memorable parts of Little Monsters on Main Street was the special “tip-toe tour” of the Haunted Mansion. Now, Disneyland’s Haunted Mansion can be a pretty scary attraction for younger kids, so during this event, Disney left the doors to the Stretching Room and Portrait Gallery wide open. This allowed kids to walk through and peek at the Haunted Mansion’s spooky interiors without actually having to board the Doom Buggies. For those brave enough to ride, they could, of course, take the full trip through the Haunted Mansion—or they could take the “chicken exit” and leave, no harm done.

Growing Success and a Bigger Event

Thanks to the event’s early success, Little Monsters on Main Street grew in size. By 1991, the attendance cap had been raised to 2,000 kids, and Disneyland added more activities like magic shows and hayrides. They also extended the event’s hours, allowing kids to enjoy the festivities until 10:30 p.m.

In 2002, the event moved over to Disney California Adventure, where it could accommodate even more kids—up to 5,000 in its later years. The name was also shortened to just Little Monsters, since it was no longer held on Main Street. This safe, family-friendly Halloween event continued for several more years, with the last mention of Little Monsters appearing in the Disneyland employee newsletter in 2008. Though some Cast Members recall the event continuing until 2012, it eventually made way for Disney’s more public-facing Halloween events.

From Little Monsters to Mickey’s Not-So-Scary and Oogie Boogie Bash

Starting in the early 2000s, Disney began realizing the potential of Halloween-themed after-hours events for the general public. These early versions of Mickey’s Halloween Party and Mickey’s Halloween Treat eventually evolved into today’s Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party and Oogie Boogie Bash. Unfortunately, this also marked the end of the intimate, Cast Member-exclusive Little Monsters event, but it paved the way for the large-scale Halloween celebrations we know and love today.

While it’s bittersweet to see Little Monsters on Main Street fade into Disney history, its legacy lives on through these modern Halloween parties. And even though Cast Members now receive discounted tickets to Mickey’s Not-So-Scary and Oogie Boogie Bash, the special charm of an event created specifically for Disney’s employees and their families remains something worth remembering.

The Merch: A Piece of Little Monsters History

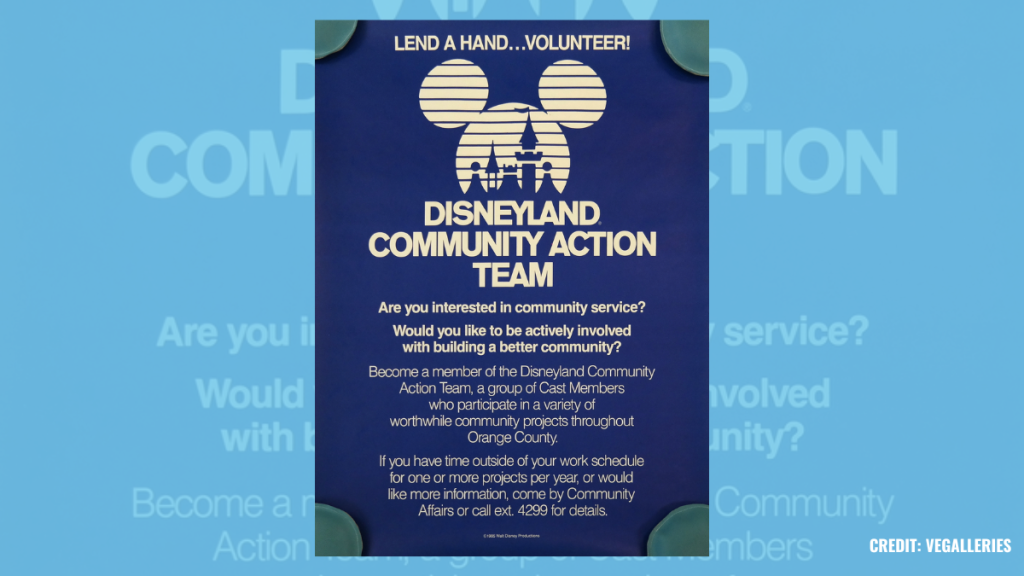

For Disney collectors, the exclusive merchandise created for Little Monsters on Main Street is still out there. You can find pins, name tags, and themed pillowcases on sites like eBay. One of the coolest collectibles is a 1997 cloisonné pin set featuring Huey, Dewey, and Louie dressed as characters from Hercules. Other sets paid tribute to the Main Street Electrical Parade and Pocahontas, while the pillowcases were uniquely designed for each year of the event.

While Little Monsters on Main Street may be gone, it’s a fascinating piece of Disneyland history that played a huge role in shaping the Halloween celebrations we enjoy at Disney parks today.

Want to hear more behind-the-scenes stories like this? Be sure to check out I Want That Too, where Lauren and I dive deep into the history behind Disney’s most beloved attractions, events, and of course, merchandise!

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment

The Story of Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party: From One Night to a Halloween Family Tradition

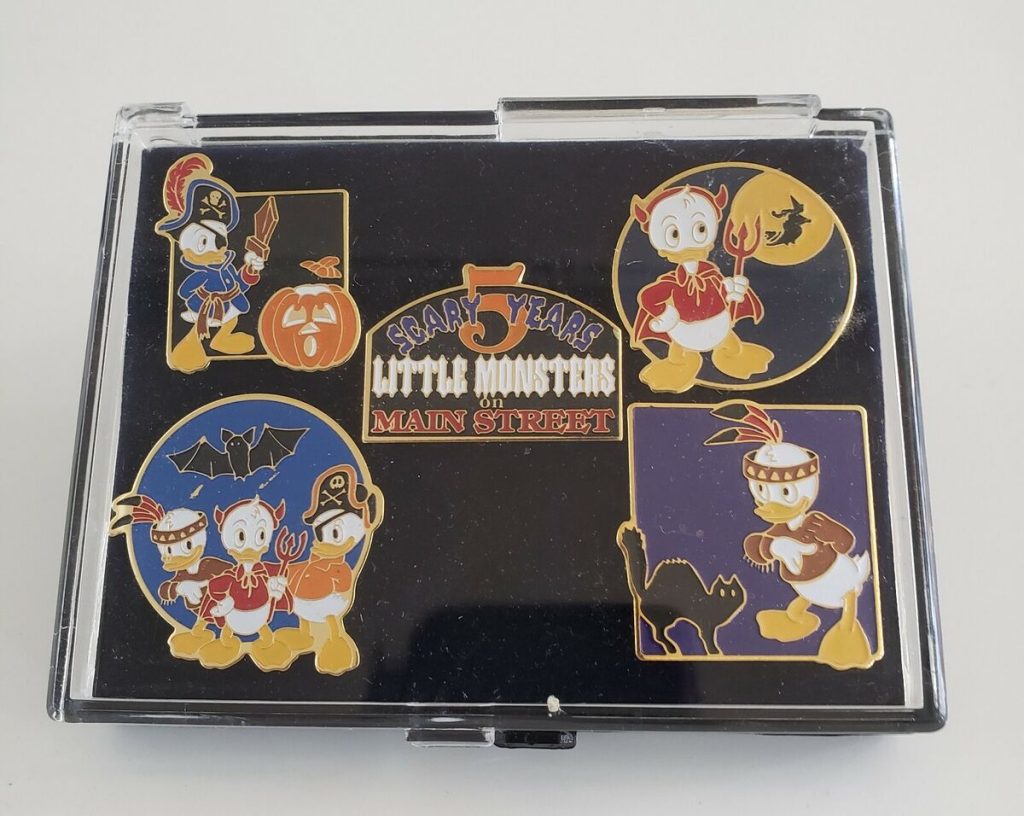

The spooky season is already in full swing at Disney parks on both coasts. On August 9th, the first of 38 Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party (MNSSHP) nights for 2024 kicked off at Florida’s Magic Kingdom. Meanwhile, over at Disney California Adventure, the Oogie Boogie Bash began on August 23rd and is completely sold out across its 27 dates this year.

Looking back, it’s incredible to think about how these Halloween-themed events have grown. But for Disney, the idea of charging guests for Halloween fun wasn’t always a given. In fact, when the very first Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party debuted on October 31, 1995, it was a modest one-night-only affair. Compare that to the near month-long festivities we see today, and it’s clear that Disney’s approach to Halloween has evolved considerably.

A Not-So-Scary Beginning

I was fortunate enough to attend that very first MNSSHP back in 1995, along with my then 18-month-old daughter Alice and her mom, Michelle. Tickets were a mere $16.95 (I know, can you imagine?), and we pushed Alice around in her sturdy Emmaljunga stroller—Swedish-built and about the size of a small car. Cast Members, charmed by her cuteness, absolutely loaded us up with candy. By the end of the night, we had about 30 pounds of fun-sized candy bars, making that push up to the monorail a bit more challenging.

This Halloween event was Disney’s response to the growing popularity of Universal Studios Florida’s own Halloween hard ticket event, which started in 1991 as “Fright Nights” before being rebranded as “Halloween Horror Nights” the following year. Universal’s gamble on a horror-themed experience helped salvage what had been a shaky opening for their park, and by 1993, Halloween Horror Nights was a seven-night event, with ticket prices climbing as high as $35. Universal had stumbled upon a goldmine, and Disney took notice.

A Different Approach

Now, here’s where Disney’s unique strategy comes into play. While Universal embraced the gory, scare-filled world of horror, Disney knew that wasn’t their brand. Instead of competing directly with blood and jump-scares, Disney leaned into what they did best: creating magical, family-friendly experiences.

Thus, Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party was born. The focus was on fun and whimsy, not fear. Families could bring their small children without worrying about them being terrified by a chainsaw-wielding maniac around the next corner. This event wasn’t just a Halloween party—it was an extension of the Disney magic that guests had come to expect from the parks.

Disney had some experience with seasonal after-hours events, most notably Mickey’s Very Merry Christmas Party, which had started in 1983. But the Halloween party was different, as the Magic Kingdom wasn’t yet decked out in Halloween decor the way it is today. Disney had to create a spooky (but not too spooky) atmosphere using temporary props, fog machines, and, of course, lots of candy.

A key addition to that first event? The debut of the Headless Horseman, who made his eerie appearance in Liberty Square, riding a massive black Percheron. It wasn’t as elaborate as the Boo-to-You Parade we see today, but it marked the beginning of a beloved Disney Halloween tradition.

A Modest Start but a Big Future

That first MNSSHP in 1995 was seen as a trial run. As Disney World spokesman Greg Albrecht told the Orlando Sentinel, “If it’s successful, we’ll do it again.” And while attendance was sparse that night, there was clearly potential. By 1997, the event expanded to two nights, and by 1999, Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party had grown into a multi-night celebration with a full-fledged parade. Today, in 2024, it’s a staple of the fall season at Walt Disney World, offering 38 nights of trick-or-treating, character meet-and-greets, and special entertainment.

Universal’s Influence

It’s interesting to reflect on how Disney’s Halloween event might never have existed without the competition from Universal. Just as “The Wizarding World of Harry Potter” forced Disney to step up their game with “Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge,” Universal’s success with Halloween Horror Nights likely spurred Disney into action with MNSSHP. The friendly rivalry between the two parks has continually pushed both to offer more to their guests, and we’re all better off because of it.

So the next time you find yourself trick-or-treating through the Magic Kingdom, watching the Headless Horseman gallop by, or marveling at the seasonal fireworks, take a moment to appreciate how this delightful tradition came to be—all thanks to a little competition and Disney’s commitment to creating not-so-scary magic.

For more Disney history and behind-the-scenes stories, check out the latest episodes of the I Want That Too podcast on the Jim Hill Media network.

-

History10 months ago

History10 months agoThe Evolution and History of Mickey’s ToonTown

-

History11 months ago

History11 months agoUnpacking the History of the Pixar Place Hotel

-

History11 months ago

History11 months agoFrom Birthday Wishes to Toontown Dreams: How Toontown Came to Be

-

Film & Movies8 months ago

Film & Movies8 months agoHow Disney’s “Bambi” led to the creation of Smokey Bear

-

News & Press Releases10 months ago

News & Press Releases10 months agoNew Updates and Exclusive Content from Jim Hill Media: Disney, Universal, and More

-

Merchandise8 months ago

Merchandise8 months agoIntroducing “I Want That Too” – The Ultimate Disney Merchandise Podcast

-

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment3 months ago

Theme Parks & Themed Entertainment3 months agoDisney’s Forgotten Halloween Event: The Original Little Monsters on Main Street

-

Film & Movies3 months ago

Film & Movies3 months agoHow “An American Tail” Led to Disney’s “Hocus Pocus”